DAN GOODIN

Though sloppy at times, Winnti Umbrella remain advanced and extremely prolific.

Researchers said Chinese intelligence officers are behind almost a decade's worth of network intrusions that use advanced malware to penetrate software and gaming companies in the US, Europe, Russia, and elsewhere. The hackers have struck as recently as March in a campaign that used phishing emails in an attempt to access corporate-sensitive Office 365 and Gmail accounts. In the process, they made serious operational security errors that revealed key information about their targets and possible location.

Researchers from various security organizations have used a variety of names to assign responsibility for the hacks, including LEAD, BARIUM, Wicked Panda, GREF, PassCV, Axiom, and Winnti. In many cases, the researchers assumed the groups were distinct and unaffiliated. According to a 49-page report published Thursday, all of the attacks are the work of Chinese government's intelligence apparatus, which the report's authors dub the Winnti Umbrella. Researchers from 401TRG, the threat research and analysis team at security company ProtectWise, based the attribution on common network infrastructure, tactics, techniques, and procedures used in the attacks as well as operational security mistakes that revealed the possible location of individual members.

A decade of hacks

More than 30 MMORPG companies targeted in ongoing malware attack Attacks associated with Winnti Umbrella have been active since at least 2009 and possibly date back to 2007. In 2013, antivirus company Kaspersky Lab reported that hackers using computers with Chinese and Korean language configurations used a backdoor dubbed Winnti to infect more than 30 online video game companies over the previous four years. The attackers used their unauthorized access to obtain digital certificates that were later exploited to sign malware used in campaigns targeting other industries and political activists.

Meet Hidden Lynx: The most elite hacker crew you’ve never heard of Also in 2013, security firm Symantec reported on a hacking group dubbed Hidden Linx that was behind attacks on more than 100 organizations, including the high-profile 2012 intrusion that stole the crypto key from Bit9 and used it to infect at least three of the security company's customers.

Crooks steal security firm’s crypto key, use it to sign malware In later years, security organizations Novetta, Cylance, Trend Micro, Citizen Lab, and ProtectWiseissued reports on various Winnti Umbrella campaigns. One campaign involved the high-profile network breaches that hit Google and 34 other companies in 2010.

"The purpose of this report is to make public previously unreported links that exist between a number of Chinese state intelligence operations," The ProtectWise researchers wrote. "These operations and the groups that perform them are all linked to the Winnti Umbrella and operate under the Chinese state intelligence apparatus."

The researchers continued:

Contained in this report are details about previously unknown attacks against organizations and how these attacks are linked to the evolution of the Chinese intelligence apparatus over the past decade. Based on our findings, attacks against smaller organizations operate with the objective of finding and exfiltrating code-signing certificates to sign malware for use in attacks against higher-value targets. Our primary telemetry consists of months to years of full-fidelity network traffic captures. This dataset allowed us to investigate active compromises at multiple organizations and run detections against the historical dataset, allowing us to perform a large amount of external infrastructure analysis.

The groups often use phishing to gain entry into a target's network. In earlier attacks, the affiliated groups then used the initial compromise to install a custom backdoor. More recently, the groups have adopted so-called living-off-the-land infection techniques, which rely on a target's own approved access systems or system administration tools to spread and maintain unauthorized access.

The domains used to deliver malware and command control over infected machines often overlap as well. The attackers usually rely on TLS encryption to conceal malware delivery and command-and-control traffic. In recent years, the groups rely on Let's Encrypt to sign TLS certificates.

Phishing minnows to catch whales

The groups hack smaller organizations in the gaming and technology industries and then use their code-signing certificates and other assets to compromise main targets, which are primarily political. Main targets in past campaigns have included Tibetan and Chinese journalists, Uyghur and Tibetan activists, the government of Thailand, and prominent technology organizations.

Powerful backdoor found in software used by >100 banks and energy cos. Last August, Kaspersky Lab reported that network-management tools sold by software developer NetSarang of South Korea had been secretly poisoned with a backdoor that gave attackers complete control over the servers NetSarang customers. The backdoor, which Kaspersky Lab dubbed ShadowPad, had similarities to the Winnti backdoor and another piece of malware also related to Winnti called PlugX.

Kaspersky said it discovered ShadowPad through a referral from a partner in the financial industry that observed a computer used to perform transactions was making suspicious domain-name lookup requests. At the time, NetSarang tools were used by hundreds of banks, energy companies, and pharmaceutical manufacturers.

Opsec mistakes

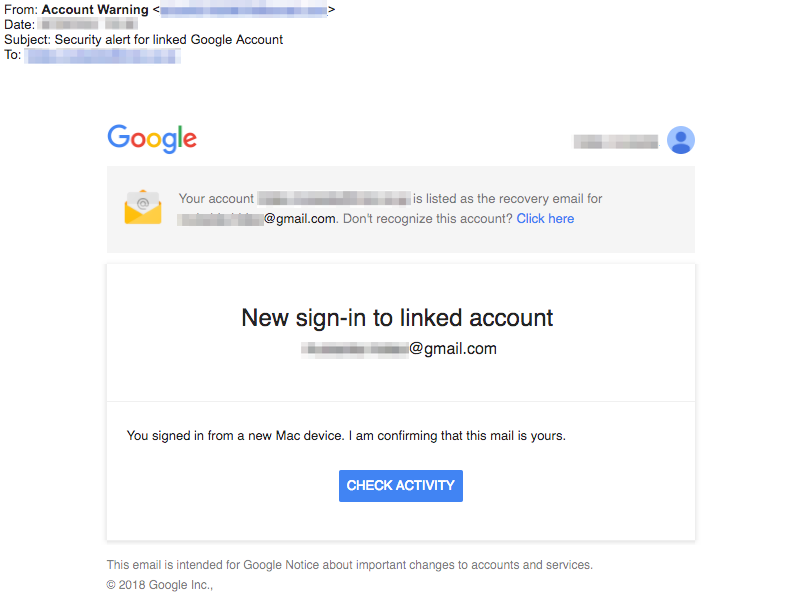

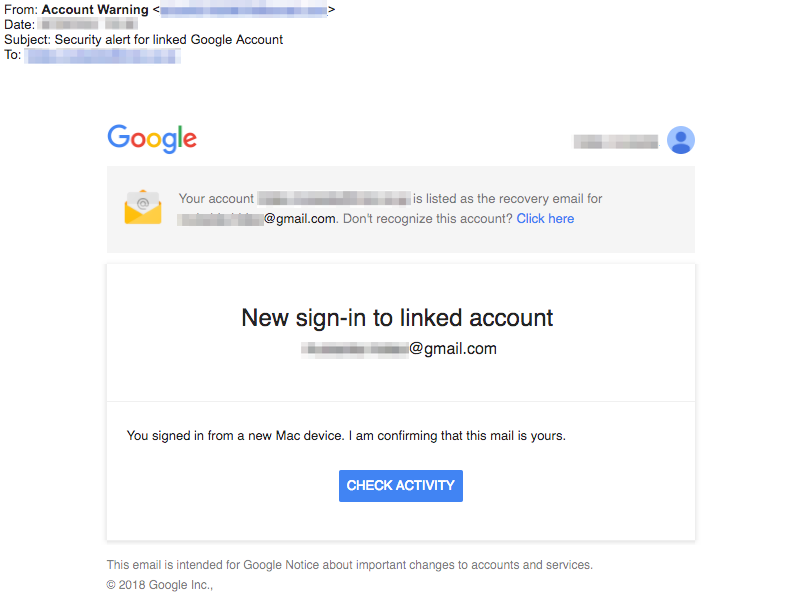

ProtectWise said since the beginning of the year, members of Winnti have waged phishing attacks that attempt to trick IT workers in various organizations to turn over login credentials for accounts on cloud services such as Office 365 and G Suite. One campaign that ran for eight days starting on March 20 used Google's goo.gl link-shortening service allowed ProtectWise to use Google's analytics service to glean key details. An image of the message appears at the top of this post.

The service showed that the link was created on February 23, some three weeks before the campaign went live. It also showed the malicious phishing link had been clicked a total of 56 times: 29 times from Japan, 15 times from the US, two times from India, and once from Russia. Chrome browsers clicked on the link 33 times, and 23 clicks came from Safari users. Thirty clicks came from Windows computers, and 26 from macOS hosts.

Attackers who got access to targets' cloud services sought internal network documentation and tools for remotely accessing corporate networks. Attackers who succeed typically used automated processes to scan internal networks for open ports 80, 139, 445, 6379, 8080, 20022, and 30304. Those ports indicate an interest in Web, file storage services, and clients that use the Ethereum digital currency.

Most of the time, the attackers use their command-and-control servers to conceal their true IP addresses. In a few instances, however, the intruders mistakenly accessed the infected machines without such proxies. In all those cases, the block of IPs were 221.216.0.0/13, which belongs to the China Unicom Beijing Network in the Xicheng District.

"The attackers grow and learn to evade detection when possible but lack operational security when it comes to the reuse of some tooling," the report concluded. "Living off the land and adaptability to individual target networks allow them to operate with high rates of success. Though they have at times been sloppy, the Winnti umbrella and its associated entities remain an advanced and potent threat."

No comments:

Post a Comment