A threatened trade war between China and America may be on hold

Chinese officials still have plenty of reasons to worry

WANG XINGXING taps the back of his dog which, on command, stands tall, shakes its legs and struts forward. It is not a well-trained pooch so much as a well-built one. Laikago, its name, looks like a miniature version of the robo-dogs that propelled Boston Dynamics, an American robotics company, to fame. Mr Wang, a boyish 28-year-old, started work on his dog as a graduate student. It can walk on uneven surfaces, carry small loads and steady itself when kicked lightly.

WANG XINGXING taps the back of his dog which, on command, stands tall, shakes its legs and struts forward. It is not a well-trained pooch so much as a well-built one. Laikago, its name, looks like a miniature version of the robo-dogs that propelled Boston Dynamics, an American robotics company, to fame. Mr Wang, a boyish 28-year-old, started work on his dog as a graduate student. It can walk on uneven surfaces, carry small loads and steady itself when kicked lightly.

Laikago is a far cry from the Boston Dynamics breed, which is sturdier, swifter and smarter. That has not stopped China’s patriotic media from asking whether the firm Mr Wang founded, Unitree, could now rival the American one. But Boston Dynamics has been at it for more than two decades. Unitree is just getting going. It plans to open its first factory soon. For now it has a cluttered workshop in the city of Hangzhou, a tech hub west of Shanghai.

Unitree is not alone in China. The government has declared robotics a priority. On the other side of Hangzhou, a university research team has also started making robo-dogs. In northern China there are at least three companies doing the same. So, reportedly, is the army. China’s robotic technology, by most measures, lags behind America’s. But the country has abundant talent, money and determination. Its robo-dogs are snapping at America’s heels.

The pooches also show how a trade conflict with America could hurt China. Mr Wang admits that their most valuable parts—their semiconductors—are mostly made in America. Were the American government to block exports of these to China, Mr Wang’s dogs would not work.

The phoney war

That is an extreme scenario. But it is the kind that China’s government and companies feel they have to consider as their country’s dispute with its largest trading partner grinds on. In the past few days, their fears have ebbed and flowed. On May 20th America’s Treasury secretary, Steven Mnuchin, said his country would refrain for now from its threat to impose punitive tariffs. “We’re putting the trade war on hold,” he told Fox News after two days of talks in Washington with Liu He, a Chinese deputy prime minister. But Mr Trump is unpredictable. He may be mindful of the outrage that Mr Mnuchin’s talk has stirred among China-sceptics in Washington. After first declaring success in the negotiations, Mr Trump later said he was dissatisfied. So Chinese officials are still preparing for the worst. And they know that even if this storm blows over, others lie ahead. Rivalry with America is getting more intense.

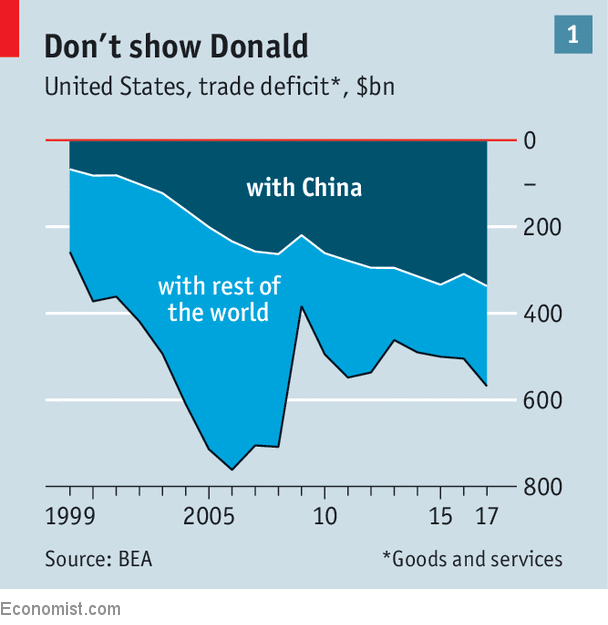

After the talks, the two sides issued a statement pledging to reduce America’s $375bn trade deficit with China “substantially”. But the agreement was strikingly light on details. The Americans wanted China to cut its trade surplus by $200bn. China refused, pledging only to buy more. Later it said it would cut import duties on cars to 15%, but that was well above the 2.5% level the Americans had demanded. Mr Trump boasted that China had agreed to buy “massive amounts” of American farm goods. But this will have a modest impact on the bilateral trade balance. It will not satisfy some American negotiators who have fumed about China’s industrial policies, calling them mercantilism gone wild.

The next steps will depend to a worrying extent on Mr Trump’s whims. He could claim China’s offers, however limited, as a victory. Or he may conclude that Xi Jinping, China’s leader, has played him for a fool and fire off a petulant tweet, nudging the two countries’ relationship back into crisis and reigniting global fears of a full-blown trade conflict.

It may be that Mr Trump does want to ease tensions with China, but only as a temporary ruse to enlist Mr Xi’s support for talks due to be held on June 12th between Mr Trump and Kim Jong Un, North Korea’s dictator. Once that event is over (if it actually takes place), Mr Trump could again turn up the heat on China. Trade is one of the few issues on which he is close to consistent. Impervious to economic logic, Mr Trump thinks that America loses when it imports more than it exports. China accounts for about three-fifths of America’s trade deficit (see chart 1).

And China is not merely contending with a truculent Mr Trump and his more hawkish economic advisers. A broad swathe of American opinion has turned against it. Businesses see a China that is determined to prop up its own companies, both at home and, increasingly, abroad. America’s national-security officials see a China that is converting economic heft into geopolitical clout and military might. Kenneth Jarrett of the American Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai says that Mr Trump’s anger about the deficit has at least helped China to wake up to the depth of foreign frustration. A quick deal in which China pledges to buy more American goods will not ease it.

Leading the charge against China on economic matters has been Robert Lighthizer, the United States Trade Representative. In March, after an investigation into China’s trade practices, he alleged that China had, time and again, stolen American technology or forced firms to hand it over. He called on China to stop subsidising industries that it deems strategic, from renewable energy to electric vehicles.

From China’s standpoint, this is a non-starter. Its plan known as “Made in China 2025” identifies ten high-tech industries and sets out global market-share goals. For policymakers in Beijing, it is their blueprint for reaching the next level of development—a reasonable desire for a middle-income country, as 19th-century Americans would have agreed. But foreign governments and businesses see it as a declaration of intent to seek global dominance.

The more the rest of the world complains, the more irascible China sounds. Mei Xinyu, a researcher in the commerce ministry, likened America’s demands to what are known in China as the country’s “unequal treaties” with foreign powers in pre-communist days. The most notorious of these accords was forced on China in 1842 by Britain after a war over British opium sales. It required China to open its doors to foreign trade and cede Hong Kong. State media have been even more colourful than Mr Mei. “Anyone who tries to hinder China’s emergence is like a mantis trying to stop a car, or an ant trying to shake a tree, and will pay a bitter price in the end,” said the Communist Party’s mouthpiece, the People’s Daily.

Despite such talk, China worries. There are four main ways in which its economy could be harmed by a trade war with America. The first is by tariffs. Although America has delayed these, they may yet happen. After the talks with Mr Liu, Mr Lighthizer vowed that if China were to fail to change its ways sufficiently, America would use “all of its legal tools”, including tariffs, to protect itself. Mr Trump has previously threatened tariffs on $150bn of imports from China. They would throw sand in the gears of Chinese commerce.

But trade fuels less of China’s growth than it used to. Exports to America were the equivalent of nearly 10% of Chinese GDP before the global financial crisis of 2008. Today they are just 4%. China has forged closer ties with many developing countries and cultivated its own domestic market. Moody’s, a credit-rating agency, estimates that Mr Trump’s initial set of tariffs, valued at $50bn, would shave only 0.14 percentage points from China’s growth rate—a rounding error for an economy that is expected to grow by about 6.5% this year.

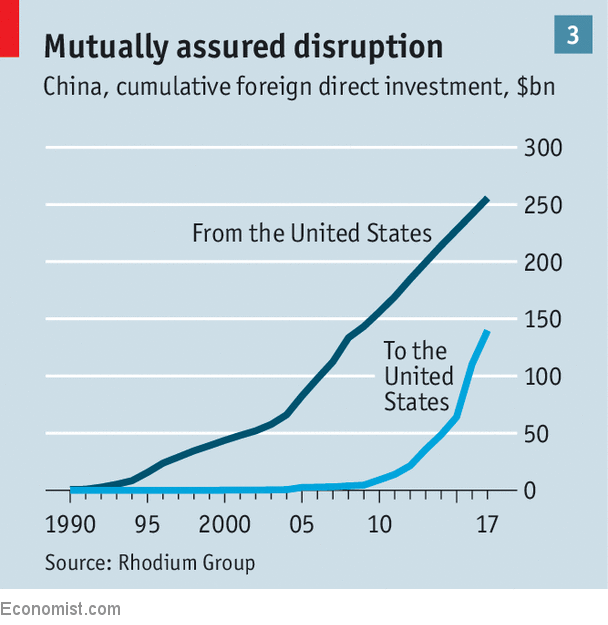

A second vulnerability is to what might be called America’s industrial policy in reverse. While China steers investment into favoured sectors, America adopts countermeasures. In recent years the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS), which checks whether deals threaten national security, has blocked Chinese acquisition of firms in industries from semiconductors to payments. The reviews will only get tougher, says Scott Kennedy of the Centre for Strategic and International Studies, an American think-tank. Previously CFIUS focused on the purchase of controlling stakes. New legislation will expand its oversight to any investment, however small, that might help a “country of special concern” (read: China) catch up with America’s technology.

Another bill would specifically restrict Chinese investments in the ten sectors targeted by the Made in China 2025 plan. If America does impose tariffs, they would also mainly focus on these ten industries. Nearly all the proposed duties affect high-tech products such as avionics and medical devices. Low-tech goods that China sells by the shipload would be mostly untouched. He Weiwen, a former diplomat, says that America’s goal is not to shrink its trade deficit but to impede China’s progress. He has a good point.

China’s third vulnerability is to blocks on American exports. A taste of this was given on April 16th when America punished ZTE, a Chinese telecoms firm, for violating sanctions against Iran and North Korea. The penalty was a ban on American sales of parts to the company. ZTE is a large global business. But around 90% of its products use American parts, especially semiconductors. The ban would render ZTE comatose, said its chairman. In the past few days Mr Trump has appeared to have second thoughts on this. On May 13th he pledged to help ZTE “get back into business, fast”. On May 22nd he said there was “no deal”, but later suggested it may only have to pay a big fine and change its management. Whatever he is pondering, China has learned a lesson about how tech superiority gives America clout.

A lot to do in seven years

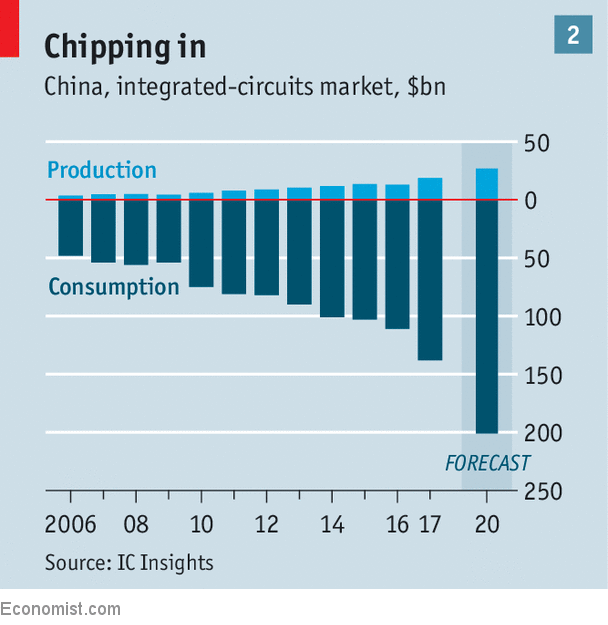

Chinese officials frankly admit that their technology is far from the global leading edge. The Made in China 2025 plan can be read as a confession of backwardness. China’s dream of becoming a semiconductor powerhouse stirs fear abroad. But it is far from that today. Its domestic production satisfies only a little more than a tenth of its demand for chips (see chart 2). China produces nearly a third of the liquid crystal displays (LCDs) in televisions and car dashboards. But about 50% of the glass substrate used in its LCDs is made by Corning, an American company. Most of the rest comes from Japanese firms. China uses more robots than any other country. But imports account for 72% of the cost of the more complex ones that it makes.

Still more alarming for China is the way that America can weaponise its financial system. By denying banks access to its market, it can freeze them out of international transactions. American politicians muse about punishing big Chinese banks for doing business with North Korea. To reduce its reliance on the dollar, China wants to make the yuan a global currency. But that would require it to open its financial system to foreigners much more widely than it is now willing to do.

China’s final area of vulnerability, and potentially its biggest, is to a united international front. Though a conflict with America would be bad, China could eventually work round it. Since the 1990s America has blocked the export of commercial satellites and their parts to China. But China was eventually able to get what it needed from Europe. Its satellite capabilities have almost caught up with America’s. (Mr Wang of Unitree says he could redesign his robo-dogs for use with non-American microchips—Laikago would live.)

It would be far worse for China if other countries were also to turn against it. Governments from Australia to Germany have already started objecting to Chinese investments on security grounds, seemingly emboldened by Mr Trump. “We’ve become Chinese takeaway in Europe but we can’t get a look at their companies in China,” says Joerg Wuttke, a former head of the European Chamber of Commerce in China. Twenty-seven European ambassadors to Beijing complained in April that China’s Belt and Road Initiative—its massive overseas investment plan—would harm global trade by subsidising Chinese firms. A multi-country alliance against China would “almost be a doomsday scenario”, says Edward Tse of Gao Feng, an advisory firm. But he believes one is unlikely to emerge. Mr Trump has a tendency to alienate his country’s usual friends.

How could China fight back? Were it just a tit-for-tat tariff battle, America would have the upper hand. America could, in theory, impose duties on its $500bn-worth of imports from China. China only buys $130bn of American goods, limiting its scope for retaliation. But it could make the brawl about more than tariffs. It could disrupt the business of American firms in China. The government has form in whipping up consumer boycotts, as South Korean retailers and Japanese carmakers can attest. China is the fastest-growing big market for American companies, from Apple to GM.

If America were to deploy sanctions such as those imposed on ZTE more widely, it would find that China can escalate matters, too. “From zero to 100, anything is possible,” says a senior Chinese government adviser. American firms have invested $250bn in China, according to Rhodium Group, a consultancy (see chart 3). The potential for asset seizures would keep executives up at night. Supply chains would be torn apart. Apple would no longer be able to use China as its main production base for iPhones. Walmart’s shelves would be bare. America’s chipmakers would lose half their sales. China could further fan the flames by frustrating Mr Trump’s efforts to bring North Korea to heel, or by flexing muscle against Taiwan or in the South China Sea (where it emerged last week that it had, for the first time, landed long-range bombers on a disputed island).

Grim, regardless

Given America’s entanglement with China, an all-out trade war would be sheer folly. But even if one is avoided, prolonged strategic competition remains likely. Some analysts say this would involve a tech war or an economic cold war. These terms are misleading. China’s integration with the global economy cannot be undone; there is no real way to cut it off as America once did to the Soviet Union. But China’s ascent could get much bumpier. It is likely to face more restrictions on overseas investments, more pressure to open its market and more scrutiny of its economic policies. China’s options for countering such amorphous efforts are not straightforward.

A complicating factor in China’s handling of the trade dispute is nationalism. Advisers have highlighted the risk of going too far to placate foreigners. Zhang Ming of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences recalls the Plaza Accord, a multinational agreement reached in 1985 under American pressure. It resulted in a soaring yen, arguably leading to Japan’s economic stagnation in later years. Mr Zhang says that China must resist such pressure. Going by their unwillingness to yield to America’s demands for deficit-reduction targets, Chinese leaders seem to agree.

Their response instead has two planks. The first involves reducing dependence on foreign technology. The punishment of ZTE has only reinforced their commitment to this strategy. China must “cast aside illusions and rely on ourselves”, President Xi said in a speech shortly after the American sanctions against the company were announced. One outcome has been more money for the semiconductor industry. China has nearly finished raising a 300bn yuan ($47bn) fund to foster domestic chipmakers, its biggest ever.

Officials are aware that excessive government meddling in industry can be counterproductive. China has previously tried but failed to create chipmaking champions. So the state’s fund managers are now operating more like venture capitalists. They are spreading cash around and monitoring returns. Much the same is happening in the other industries specified in the Made in China 2025 plan, from biotechnology to aerospace.

A go-it-alone approach to innovation rarely works. China has been most successful in industries such as high-speed rail, in which it has obtained foreign technology and combined it with domestic know-how. Hence the second plank of China’s strategy: winning foreign friends, even if not the Americans. China still needs foreign technology, so is doing what it can to stop antagonism from coalescing.

Diplomatically, it is taking a softer tack. One recent example was its support for a three-way leaders’ summit with Japan and South Korea. This was held on May 9th after years of tetchy relations. Chinese negotiators also want to give Mr Trump at least something he can claim as a victory. During the talks in Washington they promised that China would buy more farm goods and oil from America.

China has started throwing juicier morsels at foreign firms, too. It has unveiled a faster timeline for opening its banking industry to foreign investors. It has pledged to scrap limits on foreign ownership of carmakers. It has also been arguing that deals generated by its Made in China 2025 scheme will involve foreign businesses.

These steps alone will not disarm critics. Even with full control of their Chinese operations, foreign companies will encounter regulatory hurdles, written and unwritten. Foreign governments will continue to bristle as well-funded Chinese companies buy up technology. The rivalry that has brought China and America to the brink of a trade war will not abate.

But so long as China can keep enough foreign businesses and governments on side for enough of the time, it will be able to carve out space for its economic rise. Faced with obstructive foreigners, China might well find that the target date of Made in China 2025 is overly ambitious. Yet that will not induce it to give up. Made in China 2035? If that, in effect, were the outcome, China could live with it.

No comments:

Post a Comment