Aaron Bazin

When soldiers have been baptized in the fire of a battlefield, they have all one rank in my eyes.

When a young man or woman enters military service, one existential question naturally arises in his or her mind: What will combat be like? For every service member, the answer will be different. Some professional soldiers may face a true combat situation a few times in a twenty-year career. Others may go from the recruiter’s office to combat in a matter of months and return many, many times. One commonality between these two extremes is that in each, a service member has a first experience; a moment that will likely change them forever. This article describes results of a survey that sought to capture veteran perceptions of first combat experiences to inform future generations as to what they might expect under similar circumstances.

When a young man or woman enters military service, one existential question naturally arises in his or her mind: What will combat be like? For every service member, the answer will be different. Some professional soldiers may face a true combat situation a few times in a twenty-year career. Others may go from the recruiter’s office to combat in a matter of months and return many, many times. One commonality between these two extremes is that in each, a service member has a first experience; a moment that will likely change them forever. This article describes results of a survey that sought to capture veteran perceptions of first combat experiences to inform future generations as to what they might expect under similar circumstances.

There have been many great works that seek to explore what combat feels like. S.L.A. Marshall’s Men Against Fire was an important look at the human elements of combat in World War II. Then there is John Keegan’s The Face of Battle, which analysed combat across three historically important battles—Agincourt, Waterloo, and the Somme. In recent times, perhaps most well known are Dave Grossman’s works On Killing and On Combat, which describe the topic from the perspective of contemporary psychology.

This article seeks to build upon this body of knowledge by reflecting the perspectives of combat veterans today. It describes a summary of responses to an independent survey of combat veterans conducted in March 2018. For the purposes of the survey, a “combat situation” is any event where the person’s life was put at risk in direct contact with an enemy force (e.g., shooting, bombing, indirect fire, etc.). The survey consisted of fifteen multiple choice and three open-ended questions to capture different aspects of first combat experiences. The participants (N=304) were volunteers recruited through veteran-focused social media sites. The majority, 95.4 percent, served in the Army, 3.3 percent in the Marines, 1 percent in the Air Force, and 0.3 percent in the Navy. Overall, respondents’ experience spanned from Vietnam through present day, with the average having spent twelve to twenty-four months in a combat zone. The results of the survey fell into the categories of: (1) physiological, (2) emotional, (3) cognitive, and (4) action responses.

Physiological

Many psychologists assert that as the human body evolved, it developed physical reactions to stress to help increase its survivability in life-threatening situations. Once the mind identifies an acute stressor (through sight, sound, touch, taste, or smell), the body reacts almost instantaneously with a series of carefully orchestrated hormonal and physical responses. The amygdala (responsible for emotional processing) perceives danger and sends a signal to the hypothalamus (the command center for the autonomic nervous system). This can result in immediate changes such as increased heart rate, breathing, and blood pressure. At the same time, the hypothalamus sends signals to the adrenal glands to release epinephrine (also known as adrenaline) into the bloodstream. If the stressful situation continues, the brain releases hormones that prompt the release of cortisol, keeping the body on high alert. This process happens almost on auto-pilot without any conscious thought.

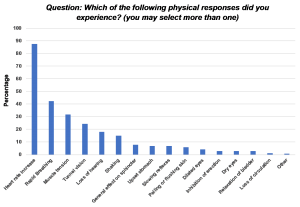

Figure 1: Physiological Responses

During periods of acute stress, there are a variety of possible physiological reactions that may occur. Figure 1 depicts combat veterans’ responses describing which reactions they recall feeling during their own first combat experiences. By far, the most prevalent response reported was heart rate increase (87.9 percent), followed by rapid breathing (42.3 percent), muscle tension (31.9 percent), tunnel vision (24.4 percent), loss of hearing (17.9 percent), shaking (15 percent), along with several others that registered below ten percent. Future generations of service members experiencing combat for the first time can expect to experience similar physiological responses.

Emotional

Understanding emotions can be much more difficult. But while there are many nuanced ways to describe the way people feel, existing theories help to explain and generalize emotions in a useful way. Robert Plutchik’s psychoevolutionary theory of emotion asserts that to help human beings survive and reproduce, eight primary emotions evolved: anger, fear, sadness, disgust, surprise, anticipation, trust, and joy. Humans feel many other nuanced emotions, but they derive from variations of these eight.

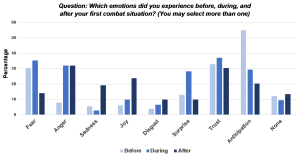

When dealing with any situation, it is helpful to put emotions in context by capturing what is felt before, during, and after an event. The combat veterans surveyed reported the series of emotions depicted in Figure 2. The survey results indicated that a person’s reaction to a first combat experience will likely be very complex. Some emotions peaked and then decreased, others increased and stayed high, and some stayed about the same.

Figure 2: Emotional Responses

Understandably, fear and surprise both peaked and then reduced afterward. Anticipation peaked before combat and then reduced significantly during and after. Anger, sadness, joy, and disgust generally increased throughout the event. Finally, trust remained a common emotion before, during, and after. Here, these results indicated that a solider could expect to experience a wide range of emotions at the same time and even feel emotions that seem to contradict one another (e.g., sadness and joy).

Cognitive

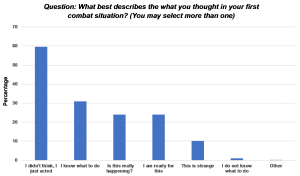

The next questions examines what respondents thought during their first combat experiences. What any one person thinks in any situation can vary greatly. As Figure 3 depicts, the clear majority of survey respondents reported that they did not think at all, they just acted (59.6 percent). The second and fourth most common thoughts related to confidence in one’s own abilities. The third and fifth most common thoughts related to disbelief and the strangeness of the situation. Because automatic response is the most common reaction, these findings reinforce the importance of repetitive and realistic training that will prepare service members to take an appropriate action with minimal cognitive burden.

Figure 3: Cognitive Responses

Actions on Contact

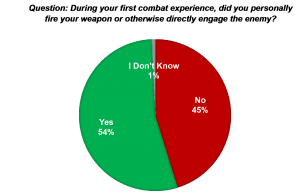

One of the more controversial aspects of S.L.A. Marshall’s work concerned the number of front-line soldiers that fired their weapons in World War II (less than 25 percent) and in Korea (50 percent). Even though many saw his research as insightful, his use of open-ended questions during after-action reviews, lack of documentation, and overall methodology have drawn criticism from many, as recently as 2003 and 2012. However, despite this controversy, the question remains one of interest to service members today. Therefore, the survey asked respondents if they fired their weapon or otherwise engaged the enemy (see Figure 4). In response to this question, 54 percent stated that they engaged the enemy, 45 percent stated they did not, with 1 percent stating that they did not remember.

Figure 4: Engaging the Enemy

One must ask, however, if this is even the right question to ask in the first place. In some situations, such as an explosion or indirect fire, the context of the situation does not dictate that a service member would even have a need to fire their weapon. Furthermore, the service member may have chosen to put a higher priority on accomplishing other assigned tasks. For example, a radio operator’s job could have been to coordinate medical evacuation for the wounded. Additionally, service members often use fire discipline, shooting only at targets they positively identify to conserve ammunition and avoid fratricide. Putting the inherent problems with this question aside, it is interesting that the combat veterans surveyed offered responses in line with Marshall’s previous analysis.

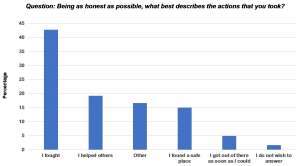

To add further insight into what the service members did when under fire for the first time, the survey asked a question designed to ascertain what actions they took (Figure 5). Respondents reported that they predominantly fought (42.7 percent) or helped others (19.2 percent). It is important to note that respondents selected “other” 16.6 percent of the time, with their individual responses varying greatly. (It is important to note that the responses lack context and one should not judge them as appropriate or inappropriate for the circumstances.)

Figure 5: Action Responses

Recommendations

The survey asked combat veterans about the quality of their training and what recommendations they would give to future service members. Even though some of the survey respondents said that there is no way to truly prepare, the majority stated that their training prepared them very well (59.3 percent) or somewhat (32.2 percent) for their first combat experience and stressed the importance of realistic training. One veteran offered a list that was a very representative summary of other responses:

Do not panic.

Pay attention to everything in your environment.

Do not let your guard down.

Remember your training it works.

Sometimes you will have to improvise.

Be aggressive but not reckless.

If your gut is telling you that there is something wrong go with it.

Overall, the veterans that participated in this survey were more than willing to share their personal experiences, even if they were embarrassing or unfavorable. Some indicated that as they experienced more combat situations they acted differently and improved their effectiveness and efficiency. It would be difficult, but further research could give increased insight into this critical learning curve and provide insight into how to maximize it.

Limitations

When looking at the validity of a survey like this there are some important things to keep in mind. One threat to validity is that survey participants must be assumed to have the required experience, to recall their experiences accurately, and to have responded truthfully. Additionally, survey participants could always provide answers that put them in the most favorable light or ones that they think the researchers are after, which could also invalidate the results.

It is also important to keep in mind that even though there were observable commonalities, each combat experience will be different and each person could react in a different way. Combat is dynamic, and even though this survey indicates there are some common responses, future situations and experiences may very well be much different. Therefore, these results only indicate what others may experience in similar circumstances in the future. There are no certainties.

Conclusion

No two first combat experiences are the same. The survey described in this article reflects the experiences of combat veterans in the hope that those that face the similar challenges may do so with a deeper understanding about themselves and those around them. This survey represents only a snapshot and more research is needed into what service members feel, think, and do when they first face combat to understand it better.

Overall, the first time a service member faces a real combat situation is often a critical moment of self-actualization. Simply put, once a service member knows battle first hand and survives, he or she will likely never be the same again. The fact remains, the more new service members can learn from the experiences of those that have gone before them, the better they can prepare themselves for what may lie ahead.

Aaron Bazin is a retiring US Army officer who served Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Iraq, Qatar, Kuwait, UAE, Bahrain, and Jordan. He is recipient of the Combat Action Badge as a survivor of the 2008 Marriott Hotel bombing in Islamabad, Pakistan. He holds a Doctorate in Psychology and currently serves at NATO Allied Command Transformation in Norfolk, Virginia. Aaron can be contacted at aabazin@gmail.com.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the US Army, Department of Defense, any other agency of the US government, or NATO.

No comments:

Post a Comment