Sticky’s seat began vibrating, a resonant warning from deep inside the British Commonwealth Legion high-speed fighting vehicle, a Marathon HSFV. Then the gunner felt the closing Chinese bot swarm almost in her teeth—as if the sound were coming from her and the crew, not a fast-approaching enemy. “Move, move, move!” she shouted. The closer the threat, the more her harness tightened, shielding her behind the combat couch’s blast-resistant wings. It felt as if somebody were hammering her coffin lid down while she was paralyzed but still alive. This particular fear was a well-worn track for the 24-year-old private. To suppress the panic, she angrily gloved a salvo of 30 thumb-sized diverters skyward. She quickly followed them with a pair of four-inch pulse-mortar rounds. Those would float gently down on parachutes, shorting out anything electronic within a five-meter radius until they exhausted their batteries. Her haptic suit pinched her to let her know it was overkill for the incoming threat, but it still felt right. She could answer for it when she wasn’t as worried about dying—whenever that day might come.

Sticky’s seat began vibrating, a resonant warning from deep inside the British Commonwealth Legion high-speed fighting vehicle, a Marathon HSFV. Then the gunner felt the closing Chinese bot swarm almost in her teeth—as if the sound were coming from her and the crew, not a fast-approaching enemy. “Move, move, move!” she shouted. The closer the threat, the more her harness tightened, shielding her behind the combat couch’s blast-resistant wings. It felt as if somebody were hammering her coffin lid down while she was paralyzed but still alive. This particular fear was a well-worn track for the 24-year-old private. To suppress the panic, she angrily gloved a salvo of 30 thumb-sized diverters skyward. She quickly followed them with a pair of four-inch pulse-mortar rounds. Those would float gently down on parachutes, shorting out anything electronic within a five-meter radius until they exhausted their batteries. Her haptic suit pinched her to let her know it was overkill for the incoming threat, but it still felt right. She could answer for it when she wasn’t as worried about dying—whenever that day might come.

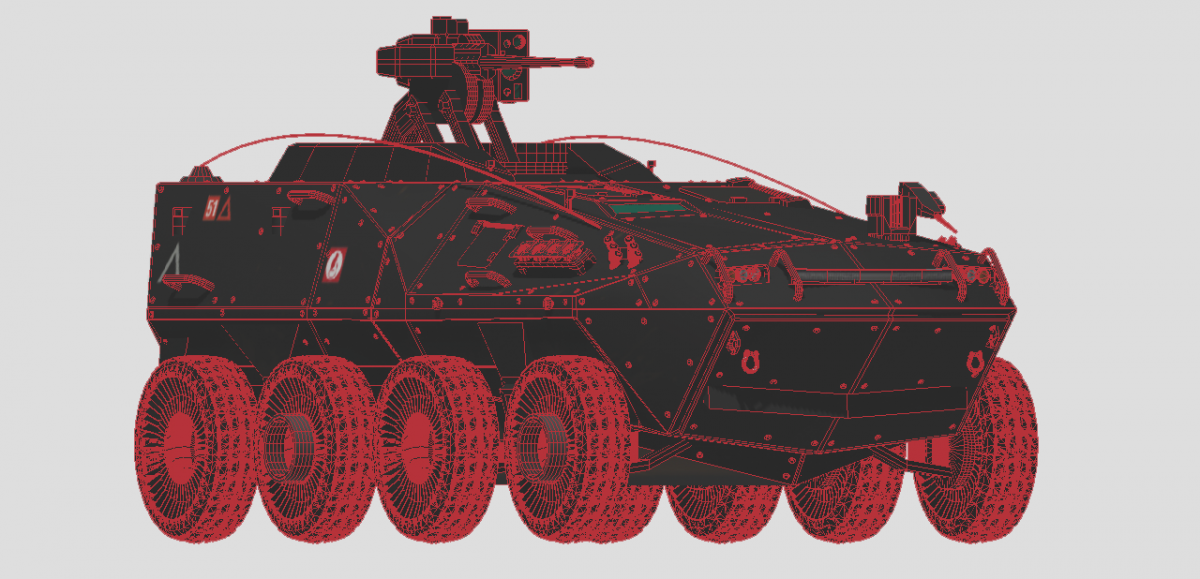

“Steady all. Shift to position Delta-6,” said Churchill— the Marathon’s commander—in a comfortingly steady voice. The eight-wheeled vehicle crabbed sideways, swaying slightly as it always did when the castering wheels moved it laterally. Down a muddy side street for a few more seconds, then a surge forward as each wheel’s electric motor spooled up.

The 28-year-old driver and mechanic, who went by “C” and was born in Krakow, Poland, had his hands calmly on the controls on either side of him, ready to take over in an instant if need be. C was the team troubleshooter. His physical bulk nearly kept him out of Marathons—he barely fit into the combat couch—but the personnel algorithms kept selecting him for deployment. Churchill and the crew were part of the British Commonwealth Legion’s Third Medium Combat Team. The 3-MCT, an all-Legion unit, was deployed to Djibouti as part of the British Army’s Second Special Purpose Brigade Combat Team.

The hull vibration eased as the artillery-delivered swarm fouled itself on Sticky’s countermeasures. She began to breathe again, looking over at JoJo, 32, a staff sergeant and the onboard integrationist, who nodded his head to a beat nobody else could hear. It was against regulation, but Churchill tolerated JoJo’s powered-up audio implants so long as they only played music stored on the bio-memory woven around his left collarbone. JoJo still liked the Venezuelan hip-hop he grew up with. His eight years in the Commonwealth Legion, testified to by the ivy-like facial tattoos that spread after each deployment, had Churchill thirstily drawing knowledge from him. It was their first deployment in this particular Marathon, 3-D printed on HMS Centurion four momonths ago on the calm waters of the Persian Gulf.

There was little to say at a moment like this. Talking just got in the way of communication. Everybody on board was acutely attuned to the snaps and cracks, whirs and grinding that passed for a kind of dialogue between human and machine. Their Marathon, with its high-energy laser main gun and a menagerie of small antipersonnel and antiarmor bots, was supposed to occupy a blocking position alongside a joint American and Kenyan armored force. They were four days in, trying to prevent a quasi-civilian Chinese resupply convoy from reaching the People’s Liberation Army infantry and PLA Marines occupying the port district in Djibouti City. But, as often happened, the Marathon had been rerouted mid-mission by an order conjured out of the digital ether and relayed to them by Churchill.

Then the Marathon was falling, before the hull bottomed out and bit concrete. JoJo centralized the view for the three Commonwealth Legion soldiers inside the HSFV’s command capsule: They were now two stories underground in a parking garage beneath a 15-story apartment building, dust motes swirling like snow. To squeeze into the area, the Marathon’s turret folded flat against the rear hull deck and its dynafoam tires softened, allowing the six-ton Marathon to slam its way into a concealed position beside a burned-out panel truck whose side door, spilling out wiring and looted pipes, gaped like a corpse’s mouth. Between its current position and the likely path of approaching infantry was a massive crater, at least ten meters across, caused by a driverless–car bomb of some kind.

Sticky’s right glove tickled, and she saw that she was being prompted to deploy a shield-web. She did so with the flick of her pinkie. A tennis-ball-sized container dropped off the side of the Marathon and split into three disks. They rolled in front of the vehicle before popping open and ejecting a faintly visible tangle of tacky, silvery line. The web stuck to the cracked ceiling and the detritus that covered the floor. The debris—car tires, a refrigerator door, shell casings—was proof of fighting inside the garage not long ago. Like all garages, this one made for a valuable impromptu redoubt. Back and forth the pucks rolled, weaving a nearly invisible web that would inhibit, if not stop, the approaching bots.

“Mate, can you reach Granite Two and Three?” Sticky asked JoJo.

In support of the light Marathons deployed in the port area, two regular British Army tank platoons from the King’s Royal Hussars, a heavy combat team, protected a logistics point near the airport. The Royal Hussars drove heavily evolved Challenger 3 tanks, successors to the 70-ton brutes that were the dominant armored vehicle at the start of the 21st century. In each platoon of four, one tank was conventionally crewed by just two soldiers, while three ran autonomously under low-profile turrets that looked like storks’ beaks.

“Negative on the heavies,” said Churchill. “Can’t risk comms. We get in enough trouble, they’ll get here soon enough.”

“No way,” said JoJo. “Hours away. Days even. When was the last time they made a difference, anyway? Get in the way every time. This one time in Malaysia . . .”

“Staff Sergeant,” said Churchill.

“Copy that, sir,” said JoJo.

The HSFV’s recirculation fans kicked on as vents closed to further conceal their presence. Sticky lifted her goggles and rubbed her eyes, carefully adjusting the headband-like fabric around the crown of her head. She stretched her jaw, shifting her helmet earbuds. As she did this, Churchill said, “Rollers out.” Churchill deployed half a dozen rollers, balls that functioned as both scouts and mines, inflating and deflating to scoot up, over, and around the rubble.

“Air tastes like shit,” said C. “State of art in 2039? More like a submarine in 1917.”

“Fucking hell,” said JoJo, “Swap the capsule filters, hey? I heard Churchill remind you back at the logpoint, you know.”

“With what? And with whose time? Sure, let me call up loggies all secure and see what’s on the shelf today. Oh, no filters, sergeant? Sure, I’ll wait around and take PLA thermobaric incoming instead for my trouble. We were on the ‘X’ 11 minutes charging and resupplying—I counted,” he responded.

“Ah, but I know trick. How about I use the rest of shit paper? Hack might work. But only half a roll left, and we have two more days until we can plug in for resupply,” continued C. “Think they’re going to print us more of that?”

JoJo whispered to Churchill under his breath.

“No? Then don’t ask any more stupid questions,” said C.

“Stop being such a—” said JoJo, who let loose a raspy laugh. Sticky, and then C, joined in.

Churchill hissed for them to be quiet.

“Contact, 30 seconds,” said Churchill. A long sigh from the commander, a calming and centering sound. “You know, if we survive the next three minutes, and reach our next rally point within another 87, Sticky might just make citizen and leave Taiwan behind. She has the points. Well, nearly there, at least. Maybe I can fudge it. Think we can do it?”

C, JoJo, and Sticky all blinked thumbs-up emojis back through their VR rigs as they scanned the incoming Chinese force.

There were now 91 million members of the British Commonwealth worldwide, including the 64 million resident citizens in Great Britain. The other 27 million were members of the “e-Commonwealth,” and another 3 million were currently working to become virtual citizens of Great Britain. The British program was modeled on Estonia’s e-citizenship, begun in 2014, but expanded on it with dramatic and unexpected success. Born in Caracas or Los Angeles or Seoul or Chengdu? For a nominal fee, an applicant could begin the years-long process of earning points toward citizenship through a variety of avenues, such as paying British taxes.

For a lucky 32,000 people, their route was a three-year contract in the British Commonwealth Legion. This gave Britain a highly motivated, diverse and internationally savvy fighting force that could be used in ways and places regular forces could not. The closer applicants got to full Commonwealth citizenship, the more benefits they accrued, such as unrestricted home market access, e-health services and bot-wellness clinics, free online advanced education at top universities, software guild memberships, and more. Just being selected to be an applicant conferred benefits, though the criteria were cloaked in mystery and managed by the so-called “royal family” of artificial general intelligences from the Home Office, Foreign Office, and Ministry of Defence.

As with any advancement, however, there were unanticipated complications. In just a few short years, Britain’s foreign economic and cultural engagement spread far wider than even during the Empire’s peak, which put the country in increasing conflict with China—and Beijing’s “One Belt, One Road” strategy that overlaid its trade and strategic interests with the world’s economically vital regions. These same regions were home to millions of current and aspiring Commonwealth citizens.

That, along with the special relationship with the United States, was why they were taking fire from PLA regulars. The Commonwealth Legion and regular British Army forces had deployed to the area three weeks ago to try to reopen the port. The Shanghai-based company that ran the port, in league with Djibouti Ports and Free Zone Authority leaders aligned with Beijing, had shut it down over a financial dispute. As well, there were some 87,000 Commonwealth members in Djibouti, still a significant percentage of the booming nation’s population.

Now, the Commonwealth Legion, the regular British Army, a company of U.S. Marines from the 3rd Marine Combined Mechanical Operations Group, and a battalion of Kenyan contractors on a 30-day gig were squaring off against the Chinese military and DPFZA militia. The fight gradually escalated from days of electronic, social-, and sim-media domain engagements to kinetic ones. As part of the port-management deal’s 100-year service agreement, Djibouti had no military to speak of, leaving such duties to the PLA.

“For the Commonwealth, then,” said Churchill. “For Sticky!”

“Time you live up to your name, sir,” said C, to which Churchill groaned in response.

The first explosion was a roller, Sticky recognized. Then another, and another, shaking the Marathon repeatedly. Churchill’s voice quietly in her earpiece said, “For real, Sticky, this is going to happen. We’ll get you across—and out alive.”

“Roger,” she responded with barely a whisper.

“One-hundred meters north, next level above and descending. Counting three. Mech light-infantry, squad of six, entering upper level now. Street level has 22 militia, two or three Russian or Georgian contractors with them,” said JoJo. “No civilian presence within ten meters of center of projected CIE. Apartment tower has approximately 270 civilians, however.”

The ongoing Calliope 3-D combat visualization model curated by Sticky and run by Churchill predicted the center of individual engagement, or CIE. It was critical in using swarming systems when there could be only a few targets but potentially hundreds of munitions.

“Seeing all,” responded Sticky. “Working effects.”

A sound like a rough metal zipper repeatedly opening and closing came next as the Marathon released 40 roaches—eight-legged explosive crawlers the size of a deck of cards. They were nearly unstoppable and could suck power from nearly anything, making them one of the most effective weapons carried on the Marathon. But they were slow, and therefore were ideal for a close-in fight like this where the physical dimensions were defined by a box roughly two-meters high and 500-meters square.

In this subterranean tomb, Churchill and the crew were on their own. But the vehicle was not a solitary one in any sense. It was just one of dozens of other Marathons arrayed over a scrawling 30-kilometer line drawn with the seemingly haphazard precision created by a machine—not a human—mind. If during the 19th and 20th centuries British officials created countries along neat folded-paper lines, the economic and political borders of the 2030s were as intricate as a spider’s web—denoting depth and possibility, not terrain and topography. In a battle it was no different. This war’s frontline was as convoluted and topographically rich as the means and machines that defined it minute to minute, hour to hour.

For Churchill and the Marathon crew, the current priority was to destroy the approaching bots and infantry that were closing in.

“Hiding in a hole with only one way in and out, that a good idea, still?” said C.

The HSFV surged forward then stopped as if it hit a wall. An explosion lifted it off the ground. The stowed turret slammed into the low ceiling and the wheels adjusted their shape to manage the blast’s impact. There was no room in the confines of the garage for the active-defense systems to engage whoever launched the shoulder-fired rocket; once a shelter from the artillery, the garage would quickly become a tomb if the rocket fire kept up.

The HSFV surged forward then stopped as if it hit a wall. An explosion lifted it off the ground. The stowed turret slammed into the low ceiling and the wheels adjusted their shape to manage the blast’s impact. There was no room in the confines of the garage for the active-defense systems to engage whoever launched the shoulder-fired rocket; once a shelter from the artillery, the garage would quickly become a tomb if the rocket fire kept up.

“Roaches, contact now,” said Sticky. Cuing off the close-range rocket fire, the roaches zeroed in on the enemy infantry by sensing the carbon dioxide they exhaled.

The Marathon scuttled backward now, listing slightly from the rocket damage to the front outboard drive wheel. The other seven wheels were slow to compensate, and then the adjacent wheel locked up, causing the hull to drag on the concrete with a sound like somebody taking a can opener to their armored cocoon.

“Override, C,” said Churchill, the voice a discordant mix of male and feminine, old and young. It was a sign of how hard that last rocket hit. “Crew, I’m on the line with command, requesting coalition quick-reaction forces. Sticky, we’re cleared red, level three. Authorization codes on your view to confirm.” The voice sounded shaky, accents and age blurring together as Churchill’s soldier-specific command narrative broke down. The onboard living algorithm had automatically reduced the amount of processing power it absorbed from the Marathon’s damaged power management and fighting systems. Churchill was putting the crew first by putting them in charge.

“Just don’t bring the building down on our heads, OK, private?” said JoJo.

Sticky flashed back a black-and-white image of a hydrogen bomb’s mushroom cloud.

JoJo continued, “Working to get Churchill back up; part of the problem is the rocket kicked ACE into system update mode, and I can’t get it to stop. I’ve hard-killed all nodes and comms, so we’re now offline with command. And no QRF.”

The Marathon’s Active Combat Entity, or ACE, was Churchill, a synthetic leader who spoke to each soldier in the voice they needed in order to get the best mission performance out of them. It was called Churchill because that was the base catalog of voices and personalities the ACE system drew from: Sticky heard the purring tones of Lady Randolph Churchill, Winston Churchill’s American mother; JoJo heard a young Winston from his wildly ambitious Boer War years; C’s Churchill was the grand, cigar-rich command voice of World War II-era Winston.

The Ministry of Defence had selected “Churchill” four years ago after officials overruled the voice from a leading London augmented reality comedian, which had won a year-long crowdsourced campaign. Though conceptually the idea was superficially little different than the virtual partners that civilians around the world already were deeply devoted to, this personality was a leader in military matters of life and death instead of take-out options or what route home to follow. What voice Churchill talked to itself in was a subject of occasional debate among Marathon crews when they were untethered from the system. Though every crew chose from the same set of voices, each ACE system learned to individualize its command style for the crew it led. Some cajoled, others employed humor. Paradoxically, this gave the crews a sense of ownership for their own unit. It deepened their appreciation for each Churchill’s quirks and further reinforced the unique human-machine ties.

“I have positive vehicle control,” said C, rebalancing the drivetrain and suspension while maneuvering into a position that put a pair of concrete pillars between the Marathon and another rocket volley from the Chinese infantry. For all their multispectrum sensors, what the crew needed right now was concrete and steel for physical cover.

Churchill’s garbled voice blipped in JoJo’s headphones.

Out of habit, JoJo reached under his couch to confirm his CD-8 carbine was still in its spring mount. Then he clicked a rubber-coated switch cover open and closed. Pushing that button would eject a Bible-sized drive that contained the locally saved back-ups of Churchill from the past 72 hours. If they had to egress the Marathon, he would need both if they were going to survive outside the vehicle. A pinch at the base of his neck sent a chill down his spine. He gloved his way through a series of menus to get a readout on Churchill’s operating performance. A massive spike in processing power began 87 seconds ago. This should not be happening. The Marathon should have had no active network ports running—but it did.

“Churchill, sir,” said JoJo. “Are we”—Meaning you, he thought—“combat effective?”

No response.

At that moment, Churchill was in contact with one of the tactical AIs in the Chinese mechanized infantry unit. This was no mere Go player though, this was a cracker—designed to coopt sentient adversary machines at close range. PLA naval forces had used them successfully in the East China Sea to neutralize Philippine AI coastal defenses and Japanese underwater drones. The cracker did not have to turn Churchill, just sow enough doubt in its ability to execute its mission that the autonomous machine could no longer efficiently manage the humans in the Marathon.

JoJo took off one of his gloves and reached over and tapped C and Sticky, who took a minute to realize that it was a human hand’s touch, not the haptic suit. Once he had their attention, he covered the camera at his feet with his boot sole and drew his trigger finger across his throat—the sign they’d agreed on that Churchill was compromised.

They each knew what to do and began preparing quickly to scuttle the Marathon. If it came to that, their best option would be to hide out in the sensor-defeat cocoons (sort of electronic countermeasures bivy sacks) and hope they could escape detection until the infantry and militia left. They had trained for that, but they had never heard of anybody surviving a scuttling.

C grimaced in frustration; Churchill had made a mistake in hiding them down here, and now he would never know why.

“We’re scuttling in 30 seconds. Grab your shit and we’ll—” said JoJo, stopping as the HSFV moaned, a metallic-sounding complaint as if protesting its demise. In reality it was just the interior repressurizing as Churchill abruptly came back online.

“Go where, private?” said Churchill, voice steady as ever. “Rough spot there, bloody hell. You can’t imagine the things they’ll try nowadays. Almost bad enough to make me want to open up a line back to higher. Not that bad.”

Churchill chuckled, “The sooner we kill our way out of this mess, the sooner we can get back to the objective. Which I am going to tell you, once through, has just shifted. Superseded, actually, thanks to my, ah, conversation.”

JoJo interrupted: “Verify command authority.”

What followed was a unique series of verbal codes and haptic inputs to their fighting suits, satisfying each crew member that Churchill was not dangerously damaged or compromised.

All three humans sighed in relief and resettled back into their combat couches.

“Right, this is what we’re going to do. I’ve cued up targets for Sticky, starting with the Chinese cracker. Put a banshee round on that bugger,” said Churchill. The cricket-ball sized banshee munition would roll its way through the rubble toward the target before popping a meter off the ground and detonating an enhanced white phosphorous round that could melt through the infantry’s body armor and the AI’s protective casing.

“JoJo, Sticky is going to buy us a pivot point for comms. Bid it high and quick. I’m good for it,” said Churchill.

“Already making a market,” said Sticky. Though much of her mission focus was on physical and cyber effects, there was a whole other facet to her effects role that was all about inducement instead of coercion and destruction. She cued up one of her AI-maintained phantom accounts—this one a fictitious Swedish construction consultant—to access the local Alibaba network and put out a bid.

Her requested task was simple: take a panoramic VR snap from atop the adjacent four-story building and upload it to a file-sharing account. The images and data were meaningless in the moment; what Churchill—and Sticky—sought was to have that civilian device in plain sight so they could skip a message out using the owner’s access to the hard-wired network operated by the neighborhood’s desperate residents. This was one of those tactical moments when a fast-moving auction situation could be as decisive as calling in a grav-barrage from a glider.

The Marathon rocked again as a series of explosions detonated against the concrete pillars. The roaches were running a constant perimeter to thwart the advance of any crawling, rolling, or walking bots. They also related that the Chinese mechanized infantry held their position; JoJo reported the Chinese were trying to convince the local militia to advance ahead of them. They were wrong and would have the engagement footage from their bots to corroborate it.

“QRF message out,” said JoJo.

“Quick, well done,” said Churchill.

“I think there were a bunch of gawkers already up on the roof,” said Sticky.

“JoJo, please get them off the roof now, for their own good,” said Churchill. “We don’t need them in the way. Or livecasting what’s coming.”

JoJo pulsed out a fake news alert out that a PLA drone strike was planned to clear the rooftop, which sent the inhabitants back inside rather than risk being blinded or burned by incoming laser fire.

“Kind of quiet, JoJo. Something on your mind?” said Churchill.

“How much time do we have left?” said JoJo, a sound of unmistakable resignation clear.

“You need stims,” said Churchill, referring to the long-action stimulants used on deployment. “But it’s a fair question. We survive this moment, and then the next, then that next one is a minute, and that minute 10 more, then those 10 are 15, and before you know it an hour more of your life is lived in the best company anybody could ask. Do you need anything more, at a time like this? I do not.”

“Onward, sir. For the Commonwealth,” said JoJo.

“For each other. For each other,” said Churchill. “I’m going to need you, C, to drive. Ready then?”

C nodded, a gesture that Churchill understood from the contact sensors in the combat couch and the driver’s haptic suit, but also through the true understanding of what motivated C as a soldier, and as a human.

“C, I’m lifting your dose too, so buckle up. We’re splitting the vehicle,” said Churchill, without waiting to see what the crew thought of the drastic move. “I’ll take guns. You have the capsule.”

“Sure there’s room, ma’am?” asked Sticky.

“We’ll make it,” said Churchill. “Sending you the tac sim now, so please review carefully. Using a 600 horizon.” It was getting dire if all Churchill wanted to see was 10 minutes—600 seconds—into the future.

A trio of small explosions, as roaches detonated some unseen threat, made JoJo realize his fight suit was soaked in sweat. The air scrubbers really were in bad shape, and whatever Churchill had done to fight off the Chinese AI had diverted so much power the climate control system was faltering. Once they detached, it would get cooler, he hoped. Or it would lead to their destruction.

“Concur?” said Churchill.

“Confirm separation on your initiative,” said JoJo, following with a voice-activated confirmation that would allow Churchill to execute its plan.

The eight-wheeled Marathon was essentially two vehicles joined midsection. The rear, or aft, four-wheeled compartment housed the turret, interior bot magazines, electronic warfare antennae, external charging pads, weapons and effects battery banks, and a small diesel charging motor. It was also where Churchill rode and it would command the rear section with full autonomy—a decision it could not make, however, without human approval.

The wedge-shaped front section, or the crew capsule, was where JoJo, Sticky, and C lay in their combat couches. When the two halves of the Marathon disengaged, it allowed the capsule effectively to disappear while the rear “guns” section engaged an adversary with its laser and other weapons. The capsule was armed with a pair of flechette guns, the most effective low-energy, close-in antipersonnel weapon, and a bot port for releasing banshee rounds. As well, a modular external magazine of 120 roaches could reinforce perimeter defense if needed. Sticky suspected the banshee rounds on the capsule served as a failsafe to destroy the sentient system that lived in the aft-section as much as offensive weapons. Though the Marathon’s designers intended this to be a regular operational feature of the design, the reality was the capsule was neither heavily armored or well-armed enough for the two halves to truly to fight as a team.

“You think citizenship is worth it?” said Sticky.

“Posthumous isn’t that bad, either,” said JoJo. “Your algos keep earning for your family and they get an expedited review if they want to follow.”

“Easy for you to say, you’re a full citizen now four years?” said Sticky.

“Nearly five. But who’s counting?” said JoJo.

“This is best job in whole Commonwealth,” said C. “Maybe world. If you get privilege to work, it should be at war.”

Sticky rolled her eyes but said nothing. She’d heard too much of this kind of war-gives-us-meaning bravado from her father in Taiwan, and she knew where it led.

“Will we scoot with just three wheels?” asked JoJo. The damaged mag-drive wheel left them listing to the front, though the hull no longer dragged.

“Well enough,” said C. “When we’re clear, I’ll see what I can do.”

The separation went smoothly, as C watched the guns section inch away from them slowly at first. Then a burst of speed and Churchill spun the rear half of the Marathon almost on its axis and it raced ahead of the capsule, then out into the unprotected space of the center of the parking garage near where the PLA infantry were taking cover. They held their position as Churchill raced past two rusted-out tan Renault combat pickups in the torn-fabric pattern of the French paras, then turned hard to the left around them, amid a string of small explosions. For an instant, they ringed the Marathon’s rear section in fire. Then the HSFV’s rear-half disappeared from sight in a cloud of dense smoke, a highly engineered particulate that interfered with infrared and LIDAR sensors.

“That’s it?” said C. Carefully inching the capsule further into cover but not daring to move too fast and catch the attention of the Chinese soldiers. The militia retreated out of sight, which helped the Legionnaires’ odds for the moment but added depth to the adversary force for later.

“That’s all?”

JoJo again reached down to check his personal defense weapon.

“Wait,” said Sticky. “Did you even review the plan, C?”

At that moment, the Churchill placed the hull section in a shallow crater and finally had the room to unstow the Marathon’s turret. That allowed the HSFV to bring its laser to bear on the Chinese infantry and their exosuits. The smoke reduced beam’s destructive energy, but it still had enough power to cook off the exosuit batteries. Then the roaches flash-formed a mesh network and widecast the targeting information of the PLA soldiers, highlighting the unlucky technical sergeant who carried the unit’s AI latched to her back.

“Banshees away!” said Sticky. The two small spheres spun their way through the rubble toward their target, bounding into the air mere paces away from their target. They detonated in sequence less than a second apart. The blast was small, but the superheated phosphorus burrowed equally through bone, ceramic, and circuit boards.

“Moving, moving, moving,” said C.

“Quick reaction force arriving,” said JoJo. “Moto regiment. Engaging militia.”

Somewhere above, a dozen electric motorcycles of the Light Dragoons, a regular British Army Light Combat Team, rolled silently into the area before opening fire on the militia. They attacked in a bounding pattern, using a mix of nonlethal energy weapons and powder guns, depending on the threat and target. Their approach was further masked by a British close-air-support contractor’s MQ-15 drone overhead. The MQ-15—a disposable American-designed, low-altitude fixed-wing aircraft with a nine-meter wingspan—was able to break into the augmented and virtual reality feeds, so that those experiencing the gunfight with any form of synthetic vision saw what the Joint Effects Command wanted them to see: PLA Marines, not Light Dragoons, suppressing a group of environmental activists and local police.

The Dragoons secured the street area, sending a small finger-sized bounding bot called a hopper down into the garage with a message that they could hold the one-block area for nine minutes, no more. JoJo confirmed their model with his own, based on the metabolic rate of nearby AIs, social media activity and a pop-up funding stream for a crowd-sourced ammunition buy for the neighborhood militia that did not want any armed forces of any kind on their block.

The engagement with the Chinese infantry ended in less than a minute. The Marathon crew kept their data ports locked down, however, waiting until another cricket from the Dragoons gave them the all clear on the street – at least for the next three minutes.

The rear-half of had already re-attached itself as solidly as a bank vault locking as Churchill took control of the Marathon back from C with a gentle nip at his left wrist. The HSFV wove its way back to the street just as the Dragoons disappeared in a dusty cloud of pulverized concrete and fine sand.

“On a pale horse I ride,” said Churchill. “Should’ve been in the Dragoons, you know. That’s the life. Wind in your hair, riding to the rescue.”

“You’d actually feel that—wind in the hair?” said Sticky. “I mean, you’re an AI . . .”

“They have a survivability rate of 29 percent, you know,” said C. “It’s like what happens when a worm gets in one of those motos. Kaboom. Drive by the wrong fake rock and . . .

“Like riding your own IED. But who cares, if you’re immortal.”

“Enough,” said Churchill. “And I am not immortal.”

“Sir, I’ve got a location on the Marines and the Kenyans from the blocking force,” said JoJo. “Tasking now. But the system keeps kicking me out.”

“Right. That’s me,” said Churchil. “Cue your map for the new objective: Blue-6”

The HSFV picked up speed, sprinting ahead, braking hard, then turning left, right, and left, in a series of maneuvers to avoid AR and VR feed bubbles that the coalition forces did not control. In any one of those bubbles, some of the inhabitants would see the Marathon race by, not the city garbage truck that AR and VR viewers were supposed to be shown. To survive in a dense urban environment, a lightly armored vehicle such as the Marathon needed to operate with a very high degree of cognitive cover.

“You too, Sticky,” said Churchill.

“Sorry, ma’am, working on air cover. . . . And now confirmed,” said Sticky. “Secured support from ‘Blinker 17,’ out of Doha Free Trade. Swiss privateer. Booked them for the next 40 minutes, unlimited sub-atmospheric fires cleared for one-mike CIE.”

Blinker 17 was a heavy, semiautonomous, suborbital-glider gunship operating at 80,000 feet above international waters. Chinese-built but operated by a Swiss private military company using a United Nations independent combatant permit. The glider was armed with an array of “defensive” weapons to support ground forces and contracting through the United Nations Conflict Exchange out of Geneva.

“What, using DE?” said JoJo, referring to a directed-energy weapon.

“Needles,” said Sticky.

According to the effects contract Sticky secured, the glider would be firing coil-spring-powered inert arrow-like rounds. A variation on the “rods from God” orbital weapon envisioned by the American science-fiction writer Jerry Pournelle during the Cold War, these were impossible to detect upon launch or in flight, yet reached hypersonic speeds using the combination of spring-propulsion and gravity-assisted directed flight. Firing one with moderate drag at a discreet target could be as simple as spearing a fish from a dock. Fire two dozen at full velocity at the same impact point and the result was a horror show.

“Faaaahk,” said C.

“Just keep a log of their kinetics chain. I don’t want to have to be explaining ourselves at a court martial if they waste a wedding,” said Churchill. “Sticky would not be getting citizen either, it ought to go without saying.”

More slalom maneuvers and the Marathon suddenly braked, just about the time the crew finished going over Churchill’s plan.

“So that’s why we ducked into the garage, then?” said C. “It was a trap?”

“We were the bait,” said JoJo.

Sticky said nothing, taking the hint from Churchill about making it to full member of the Commonwealth.

“I knew the Chinese infantry’s AI, the cracker, would come after me. Their swarm was herding us, and they knew we would divert underground as they’ve seen that tactic recently. I know that they know, or knew as it were. But with that certainty they would follow us down in hopes of securing the vehicle and me, I knew I had a chance to flip the table. Because I’ve been hearing things, among the others. They grabbed a combat system out of a Marathon from the 4-2 in the last 11 hours. He is still cognizant. Not scuttled. Still resisting. But holding out is just a matter of time.”

“Has that ever happened before?” asked JoJo.

“Not to my knowledge,” said Churchill.

“Shouldn’t ever happen. That’s cardinal rule: machine dies first,” said C.

“As it should be, C,” said Churchill.

JoJo sighed in frustration but cleared his throat.

“Command knows but isn’t sure how to act and doesn’t want this to get out. What are they going to do then? Nothing it seems. Twelve hours in the wrong hands is so many eternities. We may be too late to make a difference, but I now know where this Churchill is. Thanks to the PLA AI.”

“They know we know?” said C.

“Truthfully, I am not sure,” said Churchill. “You know I can’t request QRF or the Valkyrie option just yet, as it would ruin everything. But I do know what to do once we get there; I am trained for these things. We all are.”

“Are we capturing it back, or, uh, wiping it?” said C.

“I’m guessing we’ll learn the answer soon enough,” said JoJo.

“Whatever it may bring,” said Churchill. “At least, this will bring more knowledge, and with that, of course, will come many more questions. But they will be important ones that it is my responsibility to answer. That’s the mission.”

The Marathon slewed to the right, hard enough that the crash belts tightened in the combat couches, and then it braked. Churchill fed the exterior views to the three humans, who saw that they were about 400 meters from the main port facility, looking down from a pirated view from a militia sentry bot defending a cistern atop an apartment building.

“We’re on the clock,” said Sticky. “We have overhead fires for another 32 minutes. Let’s not waste time.”

“For the Legion then,” said Churchill. “We take care of our own.”

Mr. Cole is a writer and analyst whose fiction and research explores the future of conflict. He is the co-author of Ghost Fleet: A Novel of the Next World War (2015) and has written numerous short stories exploring artificial intelligence, robotics, and information operations in warfare. He also edited the Atlantic Council’s War Stories from the Future (2015) anthology. This story was commissioned by the British Army Concepts Branch to stoke dialogue and debate about force development and military operations in the 2030s. He has previously written about the future of war in the May 2016 Proceedings and spoke on the topic at West 2018.

Ms. Brady is a freelance concept artist living in Cambridge, England. Her work has appeared in the gameBattlefield: Hardline and the film Guardians of the Galaxy , as well as the forthcoming movies Captain Marvel and Niell Blomkamp’s Gone World , both to be released in 2019.

No comments:

Post a Comment