A WAVE of automation anxiety has hit the West. Just try typing “Will machines…” into Google. An algorithm offers to complete the sentence with differing degrees of disquiet: “...take my job?”; “...take all jobs?”; “...replace humans?”; “...take over the world?”

A WAVE of automation anxiety has hit the West. Just try typing “Will machines…” into Google. An algorithm offers to complete the sentence with differing degrees of disquiet: “...take my job?”; “...take all jobs?”; “...replace humans?”; “...take over the world?”

Job-grabbing robots are no longer science fiction. In 2013 Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael Osborne of Oxford University used—what else?—a machine-learning algorithm to assess how easily 702 different kinds of job in America could be automated. They concluded that fully 47% could be done by machines “over the next decade or two”.

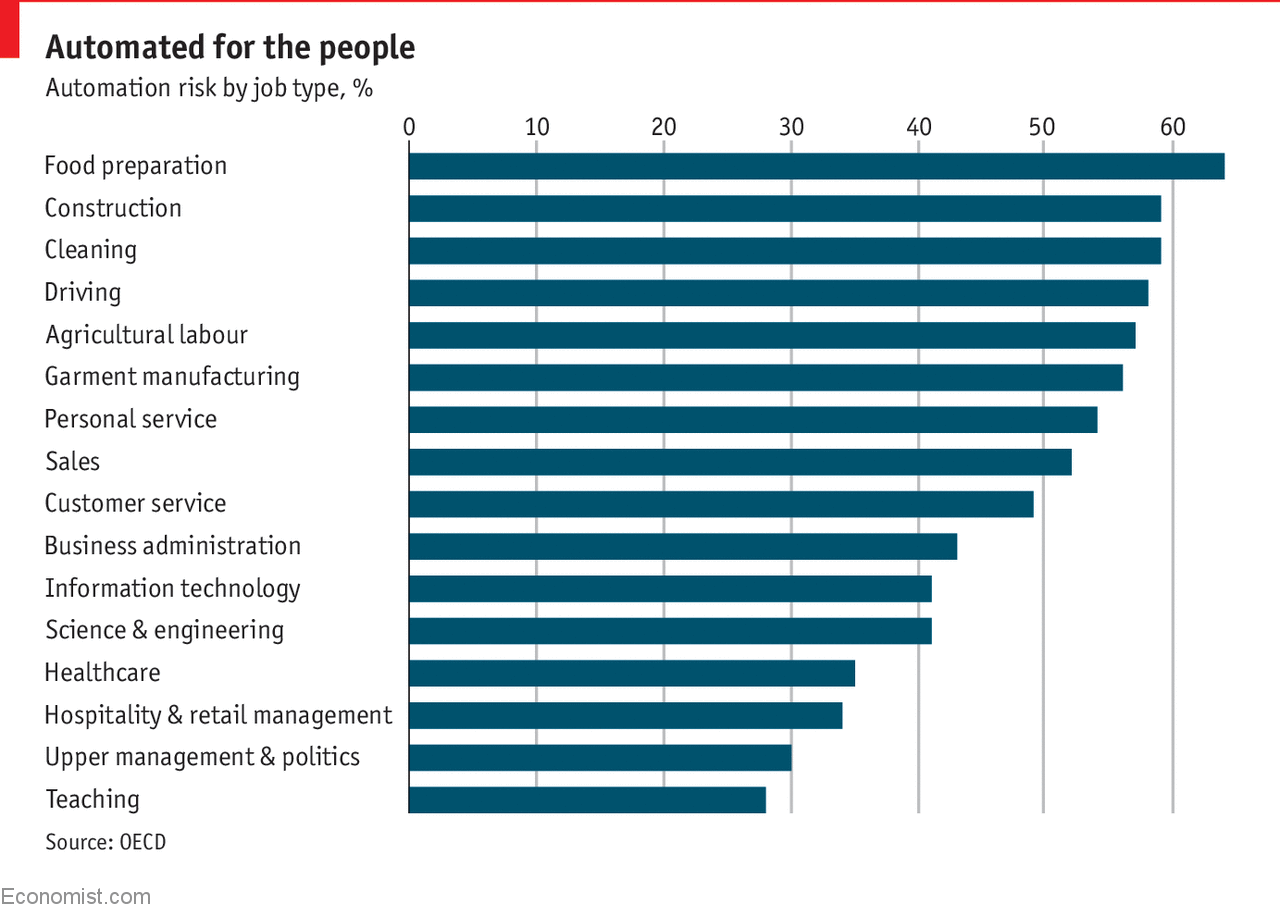

A new working paper by the OECD, a club of mostly rich countries, employs a similar approach, looking at other developed economies. Its technique differs from Mr Frey and Mr Osborne’s study by assessing the automatability of each task within a given job, based on a survey of skills in 2015. Overall, the study finds that 14% of jobs across 32 countries are highly vulnerable, defined as having at least a 70% chance of automation. A further 32% were slightly less imperilled, with a probability between 50% and 70%. At current employment rates, that puts 210m jobs at risk across the 32 countries in the study.

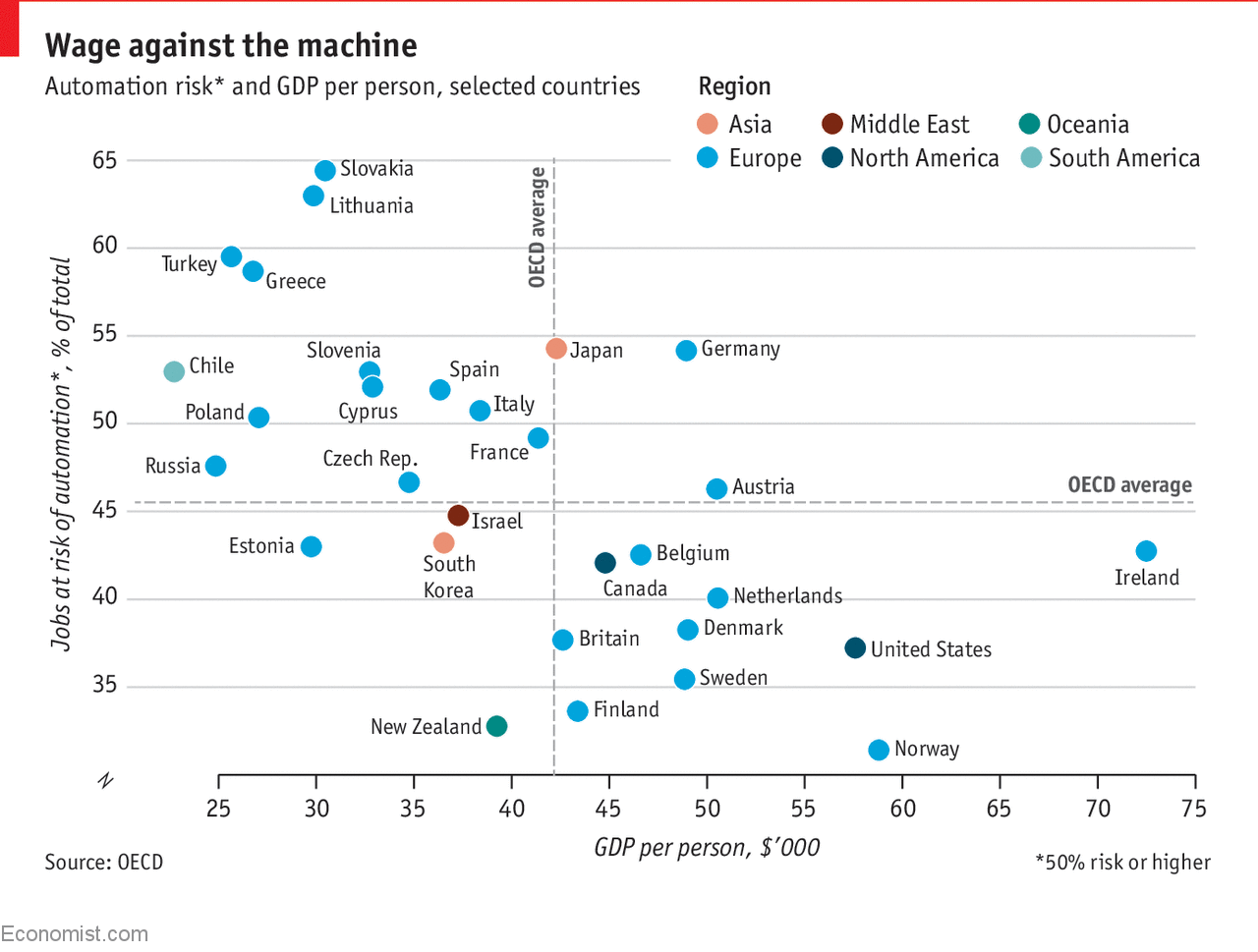

The pain will not be shared evenly. The study finds large variation across countries: jobs in Slovakia are twice as vulnerable as those in Norway. In general, workers in rich countries appear less at risk than those in middle-income ones. But wide gaps exist even between countries of similar wealth.

Differences in organisational structure and industry mix both play a role, but the former matters more. In South Korea, for example, 30% of jobs are in manufacturing, compared with 22% in Canada. Nonetheless, on average, Korean jobs are harder to automate than Canadian ones are. This may be because Korean employers have found better ways to combine, in the same job, and without reducing productivity, both routine tasks and social and creative ones, which computers or robots cannot do. A gloomier explanation would be “survivor bias”: the jobs that remain in Korea appear harder to automate only because Korean firms have already handed most of the easily automatable jobs to machines.

No comments:

Post a Comment