Anirudh Kanisetti

Far from being eternally peaceful pilgrimage sites, the Himalayas have seen centuries of brutal conflict, religious divides, wily entrepreneurship, and intellectual and cultural flourishing on par with any place in the world. The 17th and 18th centuries were particularly momentous years for the scattered, warring peoples who lived in the world’s highest mountains. Gushi Khan, the founder of the Mongol Dzungar Khanate that politically united Tibet and established the primacy of the Dalai Lama. Tibet, at the time, was very much the politico-cultural center of the Himalayan peoples, and was torn by conflict between the great noble houses and ambitious monastic schools. Appealing to Mongol aid, the Dalai Lamas eventually emerged from the chaos into the political and spiritual role through which they would rule the Tibetans until the present day. Meanwhile, a certain lama fleeing powerful rivals in Tibet had subdued most of Bhutan’s tribes, turning it into a united kingdom for the first time. From Tibet, also, came a family, supposedly descended from another great monk, who united Sikkim and extended it up to the Chumbi Valley, where it was contested with the new state of Bhutan.

Far from being eternally peaceful pilgrimage sites, the Himalayas have seen centuries of brutal conflict, religious divides, wily entrepreneurship, and intellectual and cultural flourishing on par with any place in the world. The 17th and 18th centuries were particularly momentous years for the scattered, warring peoples who lived in the world’s highest mountains. Gushi Khan, the founder of the Mongol Dzungar Khanate that politically united Tibet and established the primacy of the Dalai Lama. Tibet, at the time, was very much the politico-cultural center of the Himalayan peoples, and was torn by conflict between the great noble houses and ambitious monastic schools. Appealing to Mongol aid, the Dalai Lamas eventually emerged from the chaos into the political and spiritual role through which they would rule the Tibetans until the present day. Meanwhile, a certain lama fleeing powerful rivals in Tibet had subdued most of Bhutan’s tribes, turning it into a united kingdom for the first time. From Tibet, also, came a family, supposedly descended from another great monk, who united Sikkim and extended it up to the Chumbi Valley, where it was contested with the new state of Bhutan.

This Himalayan status quo, however, was shattered when the Gorkhassuccessfully united the warring kingdoms of Kathmandu, Patan, and Bhaktapur into the Kingdom of Nepal in 1768. The extremely martial Gorkhas, neighboured by Sikkim in the East and Tibet to the North, were constantly locked in low-intensity raiding warfare with both over the control of lucrative mountain trade routes. Borders were never clearly demarcated, for none of these states had a concept of nationhood that depended on it. There were few places that could support intensive agricultural states, giving those states that existed more of an incentive to raid. Control was exerted through forts and trade posts. Pastoralists were constantly moving between the valleys with little regard for which particular overlord claimed the grass on the mountains.

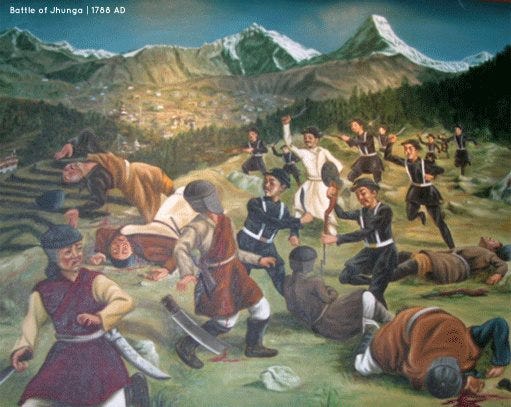

The Gorkhas attack the Tibetans. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The Gorkhas attack the Tibetans. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Within a matter of decades, the Gorkhas were powerful enough to encroach onto Tibetan territory in order to ostensibly settle a trade dispute, leading to an appeal being sent to the Kangxi Emperor of China and China’s first sustained Himalayan entanglement. Unable to convincingly defeat the Gorkhas in their mountain strongholds, the overextended Chinese agreed to a stalemate, declaring Tibet to henceforth be a Chinese protectorate and requiring Nepal to pay them tribute.

Over the course of the 19th century, however, China was torn apart by disastrous conflicts, from the Opium Wars to the Taiping Rebellion (which, to put it into perspective, had a higher casualty count than the First World War). The states of the Himalayas were left to its own devices, and the Gorkhas had plenty of other people to fight in any case. All of these players — the Dalai Lamas, the Gorkhas, Sikkim, Bhutan, China, and Britain — would make decisions that, centuries later, would end with shivering soldiers patrolling and building roads in the world’s highest mountains.

Part II: Colonisation

As the East India company expanded from Bengal into the fertile plains of North India, they could hardly have ignored the Gorkhas. Nepal was situated at the crux of Himalayan trade with Tibet, and stubbornly (if sensibly) refused to open up to the British.

Strategically speaking, the English could not leave a hostile indigenous state to their rear if they were going to decisively finish off the Marathas or the Sikhs. Of course, the Gorkhas had no lack of enemies thanks to their aggressive expansionism, and the Sikkimese were pleased to ally with the British and empower them to negotiate on their behalf. The Gorkhas, like so many subcontinental states before them, fell before the British war machine.

By the 1860s, Britain dominated the Himalayas, with Sikkim becoming a protectorate. In 1890, they negotiated on behalf of Sikkim to establish a border with Tibet (nominally with the Qing Dynasty of China, but really with the Dalai Lama). It was in British interests to have plenty of buffer states between their Indian posessions and the growing power of Russia, a strategy known rather patronisingly as The Great Game, as if it were not meant to keep millions of people under one boot or another. But, moving on..

How does one draw a border on a mountain range? By referring to the highest known geographical features. To the British, this was the mountain Gymochen. Later surveys would establish it to be the Merug La pass. The crucial point here is that the British and Chinese agreed then that the border between Tibet and Sikkim was demarcated by certain geographical features. The Bhutanese were not signatories to this treaty and did not agree to it even after becoming a British “protected state”. In 1890, the British Empire was among the world’s most powerful, and these inequal colonial-era terms hardly mattered to the Himalayan peoples, who continued to move from one valley to the next with equally scant regard for who claimed what. Over the course of a century, this too would change irrevocably, as new powers entered the mountains — the People’s Republic of China and the Republic of India.

No comments:

Post a Comment