IN THE 27 years since he became headmaster of a school in Trishal, in northern Bangladesh, Mohamed Iqbal Baher has noticed some changes in his pupils. Although boys and girls are often absent because they are helping their parents in the fields, they miss fewer lessons because of illness. Mr Baher does not recall an outbreak of cholera in the past ten years. And, although he cannot be sure, he thinks that pupils are taller than they used to be.

IN THE 27 years since he became headmaster of a school in Trishal, in northern Bangladesh, Mohamed Iqbal Baher has noticed some changes in his pupils. Although boys and girls are often absent because they are helping their parents in the fields, they miss fewer lessons because of illness. Mr Baher does not recall an outbreak of cholera in the past ten years. And, although he cannot be sure, he thinks that pupils are taller than they used to be.

If so, it is probably because they were healthier infants. In 1993-94, 14% of Bangladeshi babies aged between 6 and 11 months had suffered an attack of diarrhoea in the previous two weeks, according to their parents, who were responding to a household survey. That is an important stage in a child’s development, but also a period of great vulnerability to stomach bugs, as babies are weaned. By 2004 the proportion of stricken babies had fallen to 12%, and in 2014 it had dropped below 7%. Stunting—being extremely short for one’s age—has declined roughly in parallel.

Get our daily newsletter

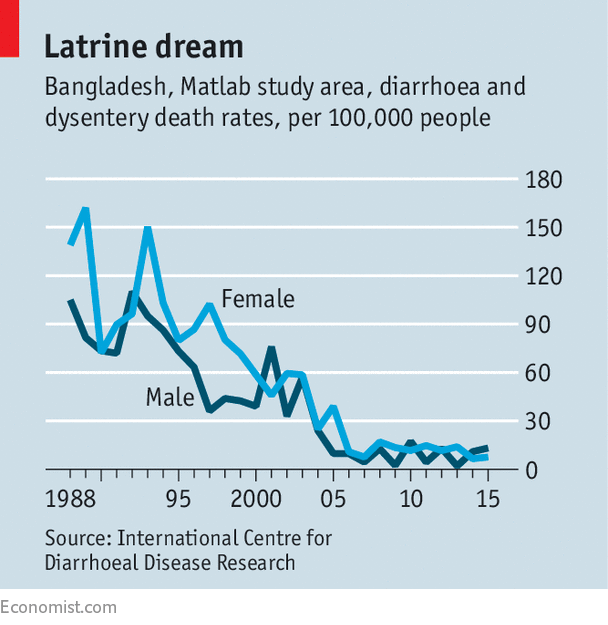

The abating of enteric disease, together with the growing use of salty rehydration solutions to treat it, has spared many lives. In Matlab, a part of Bangladesh with good data, deaths from diarrhoea and dysentery have dropped by about 90% since the early 1990s (see chart). That decline helps to explain how Bangladesh has pulled off a remarkable feat. Though it is still one of Asia’s poorest countries, with only half the GDP per person of India, Bangladesh now has a child-mortality rate lower than India or Pakistan, and indeed lower than the world average.

The most obvious explanation for Bangladesh’s success is the proliferation of outhouses in Trishal and other villages. Made of tin or palm fronds, these conceal simple pit latrines—concrete rings sunk into holes in the ground, with toilets on top. Between 2006 and 2015 a sanitation programme run by BRAC, a charity that is ubiquitous in Bangladesh, helped more than 5m households build a toilet.

What charity started, village one-upmanship has accelerated. A group of women in Trishal explain that a household toilet is now a symbol of respectability, to the extent that marriages have been called off when a groom’s family is discovered not to have one. Even in the districts where BRAC operates, two-thirds of the latrines built between 2006 and 2015 were constructed not by charities or the government, but by ordinary people.

More important, people use the latrines. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), the proportion of Bangladeshi households that defecate in the open has fallen to zero. That is probably overstating things. Other studies suggest that about 5% of households still resort to woods or roadsides, or use toilets overhanging rivers. But Bangladesh has certainly done better than other poor countries. According to the WHO, 40% of Indians defecate outdoors. The Indian government, which is in the midst of a fierce campaign against open defecation, disputes that, and claims to have cut the number of rural people relieving themselves outside from 550m to 250m since 2014. Either way, that is still far behind Bangladesh.

Janir Ahmed, a sanitation specialist at BRAC, says that villagers were reluctant to use outhouses at first. They complained about the smell and felt uncomfortably enclosed. BRAC discovered that the poorest people were more willing to listen to experts. The charity built latrines for them, then gently (and sometimes not so gently) shamed wealthier villagers into following suit. Mushfiq Mobarak, an economist at Yale University who has researched sanitation decisions, suggests that better-off people may be more likely to copy poor people than the other way round. If a wealthy person has something, you do not necessarily feel ashamed not to have it.

The other striking thing about Trishal is the abundance of drinking water. This village of 270 households has 33 water pumps. As with the outhouses, the great majority were paid for privately. Bangladesh has a thriving boring industry—teams of men who will drill tube wells dozens or hundreds of feet deep, depending on the height of the water table and levels of arsenic in the area. The water pumps are unnervingly close to the outhouses. But Mohammad Sirajul Islam, of the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research in Bangladesh, suggests that this does not matter. By testing groundwater around pit latrines, he has found that bugs can barely travel more than two metres underground.

Mr Sirajul Islam has also discovered something else. Whereas groundwater is pretty clean, the water that comes out of pumps is not. And the water stored in people’s homes is often filthy, as is the food that mothers have set aside to feed to their babies. If Bangladeshis can be persuaded to wash water pumps, pots and their hands, and to reheat food that has been allowed to cool down, all as a matter of routine, rates of enteric disease ought to decline even further. A mass killer has already been reduced to the level of a hazard. It could yet be turned into an occasional nuisance.This article appeared in the Asia section of the print edition under the headline "Beating the bugs"

No comments:

Post a Comment