Xie YuMaggie Zhang

As the Chinese government continues to gear up for what’s increasingly looking like its “techno-nationalism” push, officials are believed to have created a hit list of some 200 top firms, that it hopes to see listed on mainland bourses. Together with a set of new rules issued by the State Council, China’s cabinet, on Friday evening that focused on regulating Chinese Depositary Receipts (CDRs) offering by overseas listed tech giants like Alibaba, a campaign by Beijing is in full swing to get its most innovative companies listed on the home market.

As the Chinese government continues to gear up for what’s increasingly looking like its “techno-nationalism” push, officials are believed to have created a hit list of some 200 top firms, that it hopes to see listed on mainland bourses. Together with a set of new rules issued by the State Council, China’s cabinet, on Friday evening that focused on regulating Chinese Depositary Receipts (CDRs) offering by overseas listed tech giants like Alibaba, a campaign by Beijing is in full swing to get its most innovative companies listed on the home market.

And the country’s Party leaders, regulators, and bankers, alike, are actively now knocking on their doors.

But analysts have reservations on whether such a frenzied push will result in the desired sustained levels of innovation, or prove to be just a short-lived gold rush, led by opportunists.

The firms themselves, they add, could also face what for many is becoming a moral dilemma: a tough choice between political duty, and the sound economic reasoning needed before taking the big step to list.

“In its attempt to establish the next generation of tech ‘unicorns’ [start-ups worth more than US$1 billion], China has ironically injected nationalism into its development process,” says Brock Silvers, managing director of Kaiyuan Capital, a Shanghai-based investment advisory firm.

“But America’s innovation advantage actually results from the freedom it offers, via its capital markets.”

Guan Qingyou, head of the Rushi Institute of Finance, a respected research body based in Beijing, adds the temptation to court favour with Beijing may be very alluring, but he also questions its value.

“When certain companies become favoured by the government, all the best resources tend to flock to them. But it directly turns smart money into dumb money.

“Follow the government line rather than business sense is not encouraging innovation – in fact it actually harms it.”

The State Council on Friday issued a new set of rules on CDR offerings in the mainland market, specially designed for “innovative firms”, in a bid to boost a “strategic industry upgrading”, it said in a statement.

Similar to an ADR (American Depositary Receipt), CDRs are traded on the A-share market and represent securities in a company incorporated outside mainland China.

The securities regulator has created them with the sole purpose of allowing overseas-listed Chinese companies and unicorns to list at home, while allowing them to bypass existing restrictions, such as putting a prohibition on variable interest entity (VIE) structures and multiple share classes, and the requirement to have an unblemished track record of profitability.

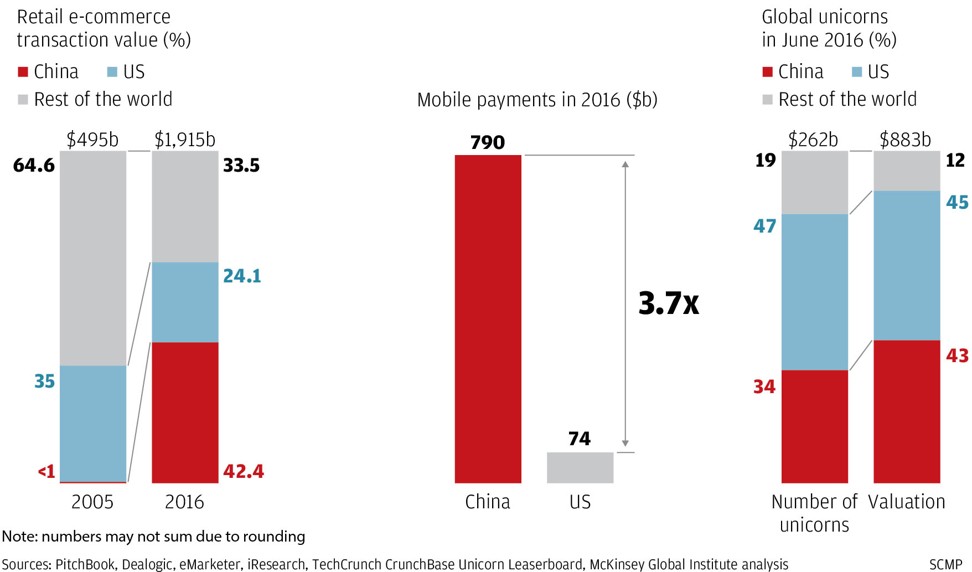

A week ago, a joint study issued by a Ministry of Science and Technology affiliate and a Beijing-based consultancy issued the 2017 China Unicorn Enterprise Development Report, showing China now has 164 unicorns, worth a combined US$628.4 billion, which has galloped well ahead of the US by number.

The most recent US figures suggest there were 132 unicorns based there at the end of 2017, valued at more than US$700 billion, from just US$35 billion in 2009.

China’s top 10 all claim individual valuations of more than US$10 billion – companies that are now being dubbed “decacorns”.

It’s a list that reads like a veritable who’s who of the country’s premier e-commerce giants: Alibaba Group Holding’s finance arm Ant Financial, taxi hailer Didi Chuxing, smartphone heavyweight Xiaomi, Alibaba Cloud, Meituan Dianping, a group buying website for locally found consumer products and retail services, CATL Battery, Toutiao.com, Cainiao, Lufax and Jiedaibao, an online platform only launched in 2014 to link lenders with borrowers.

Alibaba owns the South China Morning Post.

Ant Financial took the crown with a valuation of US$75 billion, while Didi and Xiaomi were placed second and third with US$56 billion and US$46 billion valuations, respectively. Most of those top ten have seen big jumps in valuation in the past two years especially.

The study says Alibaba invested in the most unicorns incubated in 2017 among Chinese tech giants, with a total of 29 start-ups it backed making the list, followed by Tencent (26), Xiaomi (12), Baidu (8) and JD.com (4).

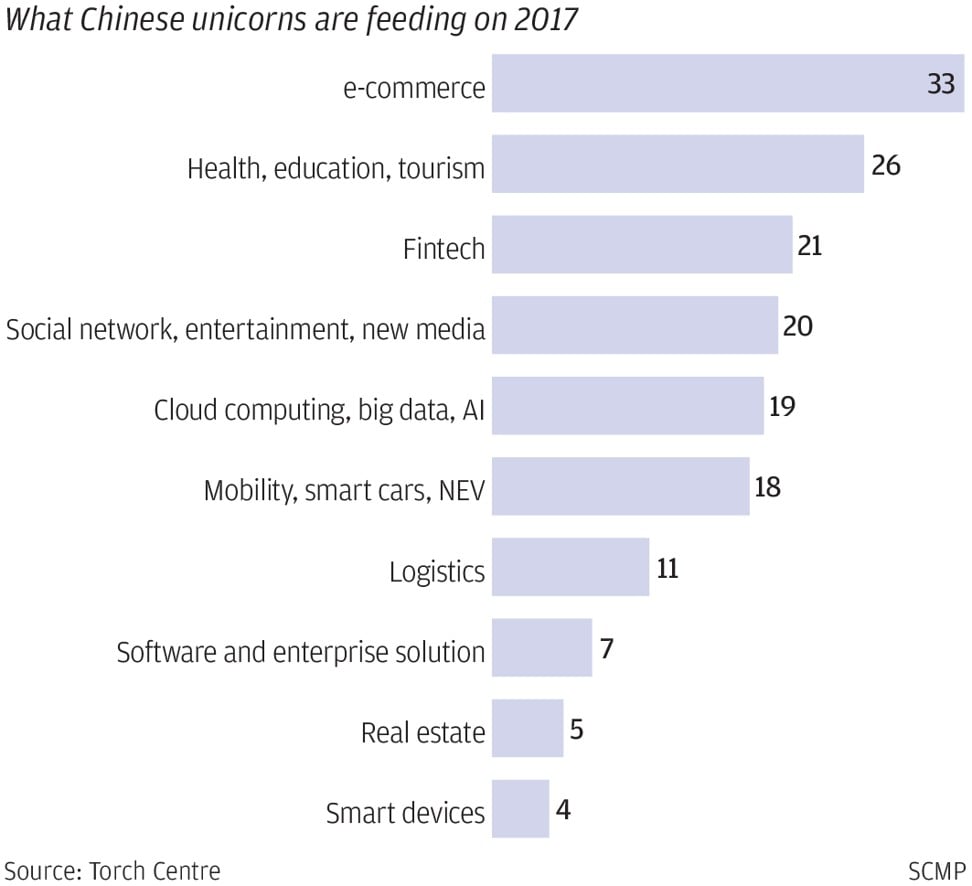

Five sectors dominate the roll-call – e-commerce, internet finance, health, cultural and entertainment and logistics – accounting for 92 of them, well over half, according to the report.

Beijing is home to 70 unicorns, 43 per cent of the total, followed Shanghai (36), Alibaba’s home patch Hangzhou (17), Shenzhen (13) and Hong Kong (4).

That latest list might not be a fully accurate picture that recognises all China’s unicorns, as valuations do fluctuate.

But what is at least clear, is that rapidly expanding tech start-ups do represent the nation’s creme of the crop in terms of innovation, and that they will play a crucial part in fuelling high-growth within the economy, with the government remaining eager to have them listed in Shanghai or Shenzhen as soon as possible.

To achieve that, the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) has set up a fast-track vetting process, and has urged the country’s top bankers to submit initial public offerings (IPOs) proposals pronto.

A prime example is Foxconn Industrial Internet, the mainland unit of Taiwan’s Foxconn, which had its planned Chinese IPO waved through after just 36 days, compared with the usual waiting time of one to two years, or longer.

Another list compiled by the CSRC has a 63-strong tally of Cayman Islands registered, but offshore listed domestic-started firms, which it is also working on to persuade them to take up CDRs in China.

Xiaomi, the country’s leading domestic smartphone maker, is now considering offering part of its shares on the domestic market, after it was approached personally recently by CSRC chairman Liu Shiyu, sources close the regulator say.

The company had previously planned an IPO in Hong Kong in early January, which could have given it a thumping valuation of around US$100 billion.

But Beijing seriously stepped up its lobbying in the hope of holding up Xiaomi as its model tech flotation, putting other previous large-scale headline foreign listings – including Alibaba and Tencent – into the shade, sources close to the regulator say.

Of the other top targets, Chinese news aggregator Toutiao.com stands out.

Translated into “Today’s Headlines”, it has already attracted hefty investment from US dollar funds, and is reported to have been approached by China’s regulators, too, dangling carrots to list at home, and is poising for a mainland IPO next year, banking sources add.

Toutiao raised more than US$2 billion in its latest funding round in August 2017, boosting its valuation to more than US$20 billion, according to Reuters. Ranked fifth overall in China by total time spent online by users, the app prides itself on its machine learning algorithms to create personalised news feeds, which pulled in US$869 million in advertising revenue in 2016.

China’s vast and still growing population of internet users has helped foster a unique environment whereby tech start-ups can enjoy huge success in an unusually short period of time, according to a joint report released by US-based Boston Consulting Group, Alibaba, Baidu and Didi Chuxing in September last year.

The term “unicorn” was first coined in 2013 by US-based seed investor Aileen Lee, who chose the mythical horse-like beast with a twisted single horn to highlight how billion-dollar technology start-up were once the stuff of myth.

But the irony is that Chinese unicorns are now being created at a much faster rate than their US counterparts, added the report, which examined the development cycles of 175 from both markets over the past decade.

In 2010, almost every new-billion-dollar start-up that broke into the unicorn arena, called the US or Europe home.

It now takes just four years on average in China, however, from gestation to unicorn status, compared with a seven year-maturity in the US, says Boston Consulting.

China’s progress is even more impressive when you consider that 46 per cent of these Chinese firms – fed well by a bull market and a new generation of disruptive technology – broke through the all-important US$1 billion valuation in just two years from launch, against nine per cent of US unicorns achieving the goal within the same time frame.

As one technology news website put it recently, with the number of Chinese unicorns growing so fast, we might have to change the term into ‘dragons’ in the very near future.

No comments:

Post a Comment