DESPITE THE EXTRAORDINARY decline in interstate wars over the past 70 years, many foreign-policy experts believe that the world is entering a new era in which they are becoming all too possible again. But there is a big difference between regional wars that might be triggered by the actions of a rogue state, such as North Korea or Iran, and those between great powers, which remain much less likely. Still, increased competition between America, Russia and China poses threats to the international order and does have a military dimension.

DESPITE THE EXTRAORDINARY decline in interstate wars over the past 70 years, many foreign-policy experts believe that the world is entering a new era in which they are becoming all too possible again. But there is a big difference between regional wars that might be triggered by the actions of a rogue state, such as North Korea or Iran, and those between great powers, which remain much less likely. Still, increased competition between America, Russia and China poses threats to the international order and does have a military dimension.

This special report will concentrate on what could lead to a future conflict between big powers rather than consider the threat of a war on the Korean peninsula, which is firmly in the present. A war to stop Iran acquiring nuclear weapons seems a more speculative prospect for now, but could become more likely a few years hence. Either would be terrible, but its destructive capacity would pale in comparison with full-blown conflict between the West and Russia or China, even if that did not escalate to a nuclear exchange.

The main reason why great-power warfare has become somewhat more plausible than at any time since the height of the cold war is that both Russia and China are dissatisfied powers determined to change the terms of a Western-devised, American-policed international order which they believe does not serve their legitimate interests. In the past decade both have invested heavily in modernising their armed forces in ways that exploit Western political and technical vulnerabilities and thwart America’s ability to project power in what they see as their spheres of influence. Both have shown themselves prepared to impose their will on neighbours by force. Both countries’ leaders are giving voice to popular yearning for renewed national power and international respect, and both are reaping the domestic political benefits. Where they differ is that Russia, demographically and economically, is a declining power with an opportunistic leadership, whereas China is clearly a rising one that has time on its side and sees itself as at least the equal of America, if not eventually its superior.

Russia’s president, Vladimir Putin, wants to regain at least some of the prestige and clout his country lost after the collapse of the Soviet Union, an event he has described as the “greatest geopolitical tragedy of the [20th] century”. He believes that in the 1990s the West rejected making Russia an equal partner, and that the European Union’s and NATO’s eastward expansion jeopardised Russia’s external and internal security. In a statement on national-security strategy at the end of 2015 the Russian government designated NATO as the greatest threat it faced. It believes that the West actively tries to bring about “colour revolutions” of the sort seen in Ukraine, both in Russia’s “near abroad” and in Russia itself.

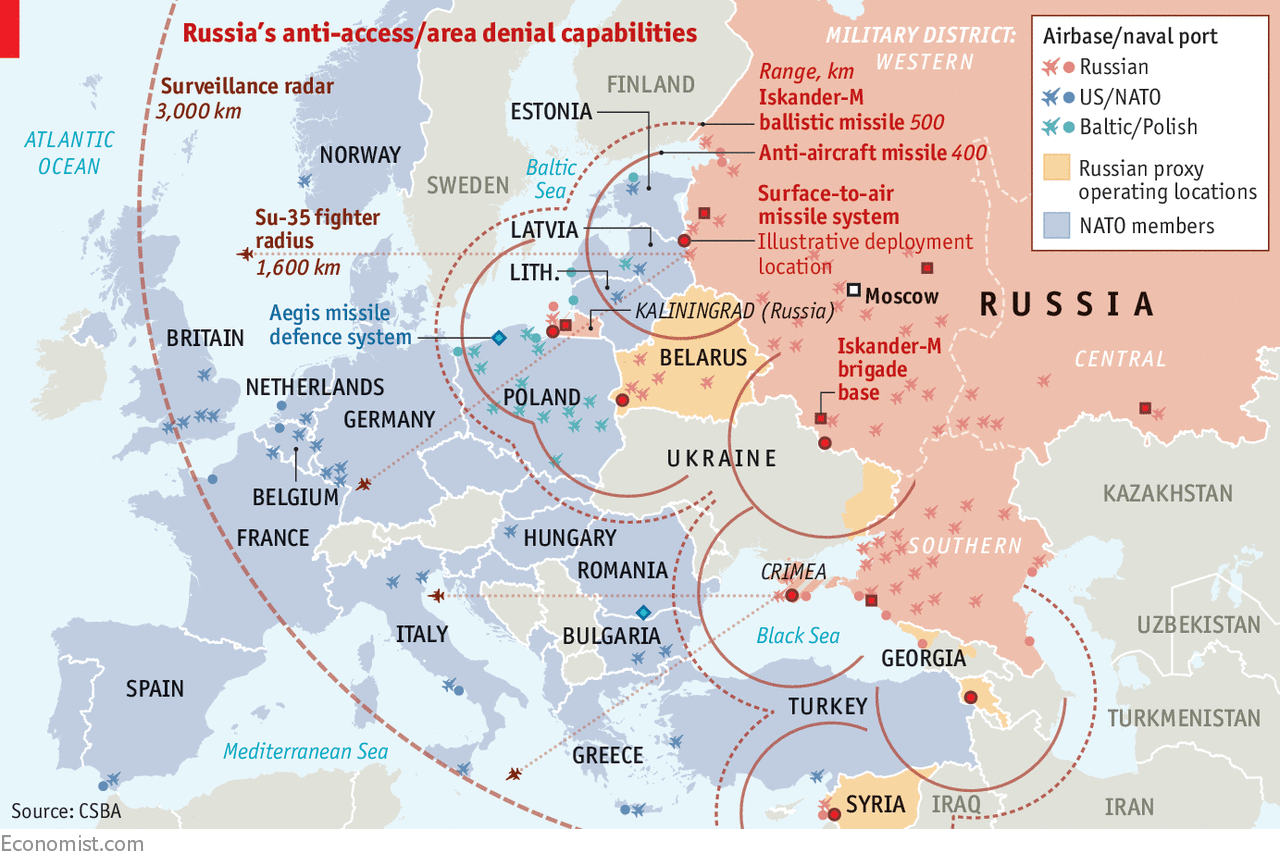

Russia’s armed forces, although no match for America’s, are undergoing substantial modernisation, carry out frequent large-scale exercises and are capable of conducting high-intensity warfare at short notice across a narrow front against NATO forces. Russian military aircraft often probe European air defences and buzz NATO warships in the Baltic and the Black Sea, risking an incident that could rapidly get out of control.

War games carried out by the RAND Corporation, a think-tank, in 2015 concluded that in the face of a Russian attack “as currently postured, NATO cannot successfully defend the territory of its most exposed members”. NATO has since slightly beefed up its presence in the Baltic states and Poland, but probably not enough to change the RAND report’s conclusion that it would take Russian forces 60 hours at most to fight their way to the capital of Latvia or Estonia.

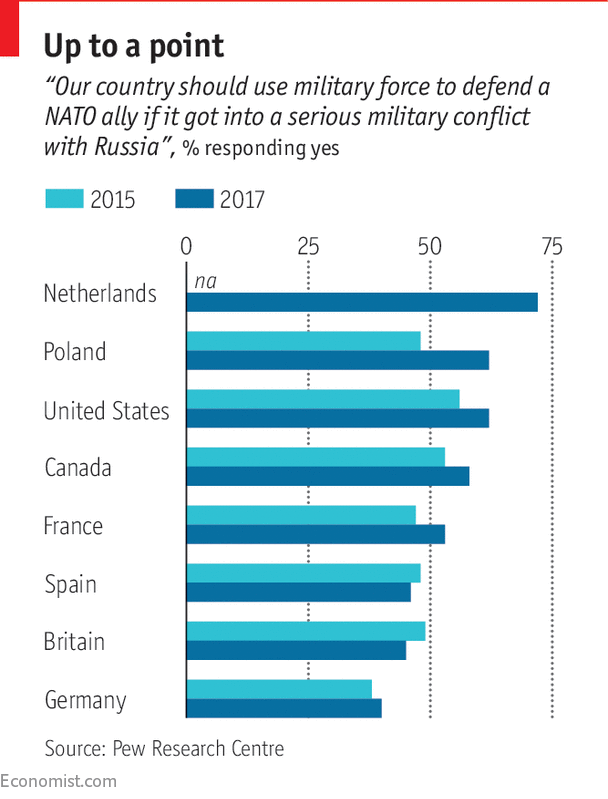

If that were to happen, NATO’s political leaders would have to choose between three bad options: launch a bloody counter-offensive fraught with the risk of escalation; exacerbate the conflict itself by threatening targets in Russia; or concede defeat, with disastrous consequences for the alliance. Domestic support for the first and second options would be fragile (in Britain and Germany a Pew survey last year found only minority backing for NATO’s Article 5 commitment to mutual defence if Russia were to attack a neighbouring alliance member, see chart). And Mr Putin’s doctrine of “escalate to de-escalate” would almost certainly bring the threat, and possibly even the use, of Russian tactical nuclear weapons to encourage NATO to throw in the towel. Mr Putin reckons, probably correctly, that he has a much higher tolerance for risk than his Western counterparts.

If that were to happen, NATO’s political leaders would have to choose between three bad options: launch a bloody counter-offensive fraught with the risk of escalation; exacerbate the conflict itself by threatening targets in Russia; or concede defeat, with disastrous consequences for the alliance. Domestic support for the first and second options would be fragile (in Britain and Germany a Pew survey last year found only minority backing for NATO’s Article 5 commitment to mutual defence if Russia were to attack a neighbouring alliance member, see chart). And Mr Putin’s doctrine of “escalate to de-escalate” would almost certainly bring the threat, and possibly even the use, of Russian tactical nuclear weapons to encourage NATO to throw in the towel. Mr Putin reckons, probably correctly, that he has a much higher tolerance for risk than his Western counterparts.

The probability of such a direct test of NATO members’ Article 5 promise is low. But Mr Putin has shown in Georgia, Ukraine and Syria that he is an opportunist prepared to roll the dice when he is feeling desperate or lucky. A second-term Trump administration, shorn of generals committed to NATO and with a more populist Republican party in Congress, might well tempt him, especially if low energy prices and a weak economy were creating mounting problems at home.

Some suggest that America and China are destined to go to war, falling into the “Thucydides trap” as encountered in antiquity by Sparta and Athens. In essence, the established power feels threatened by the rising power, which in turn feels resentful and frustrated. Graham Allison, the author of a popular book expounding this thesis, believes that “war between the US and China in the decades ahead is not just possible, but much more likely than currently recognised.”

Mr Allison’s prognosis, based on an analysis of past conflicts between incumbent powers and thrusting newcomers, may be too deterministic. Although China and America do not have anything like the shared international agenda that America had with Britain when the roles were reversed, they are bound together by a web of economic interests. Strategic patience and taking the long view comes naturally to Chinese leaders, and successive American presidents (except perhaps the current one) have tried hard to show that far from wanting to keep China in its box, they wish to see it playing a full and responsible part in the international system. The previous contests for hegemony cited by Mr Allison were not conducted under the shadow of nuclear weapons, which for all their risks remain the ultimate disincentive for great powers to wage war against each other.

Moreover, says Jonathan Eyal of RUSI, a defence think-tank, demographic factors and changing social attitudes in China suggest that there would be little popular appetite for conflict with America, despite the sometimes nationalistic posturing of state media. Like other developed countries, the country has very low birth rates, fast-decreasing levels of violence and large middle classes who define success by tapping the latest smartphone or putting down a deposit on a new car. In a culture of coddling children prompted by the one-child policy, Chinese parents would probably be extremely reluctant to send their precious “snowflakes” off to war.

No coffins, please

Even in Russia, where Mr Putin has encouraged a revival of a more macho culture, he wants to avoid casualties as far as possible. In his view, the thousands of coffins returning from Afghanistan in the 1980s were partly to blame for the collapse of the Soviet Union, so he has gone to extraordinary lengths both to minimise and conceal the deaths of any conscripted troops in Ukraine. In Syria, he has used private military contractors wherever possible.

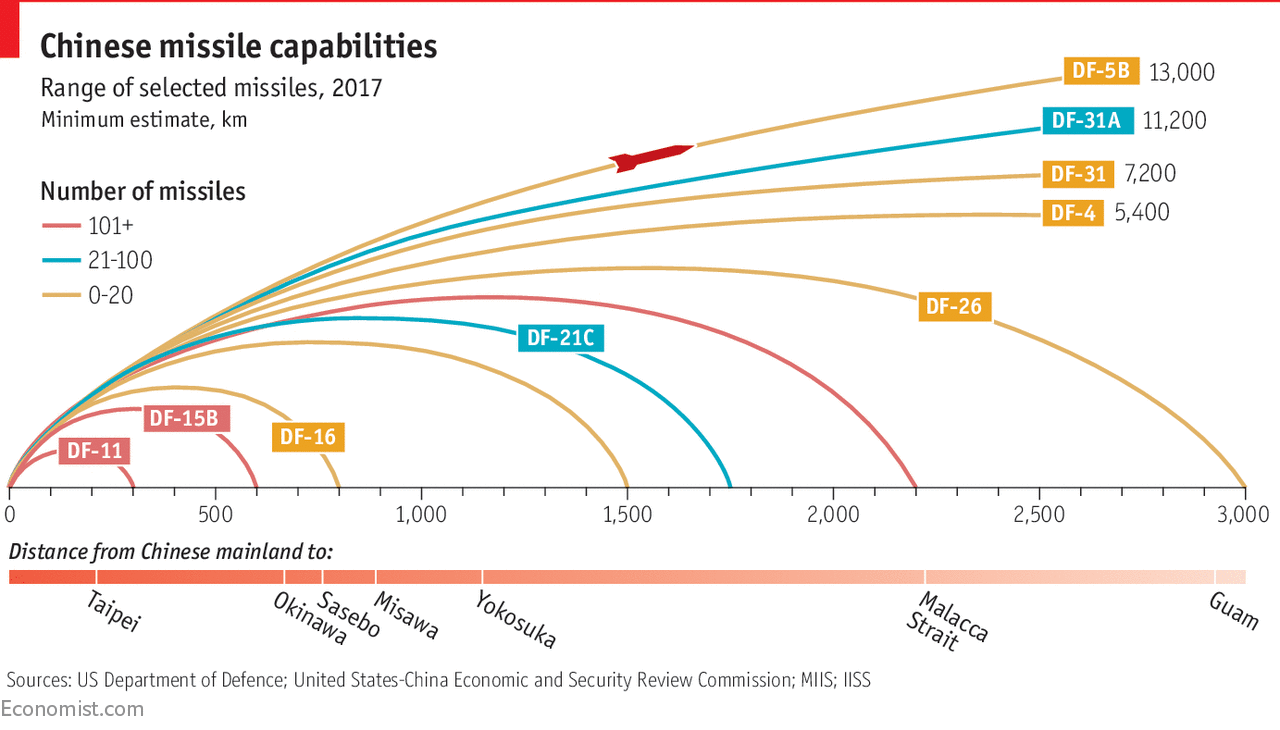

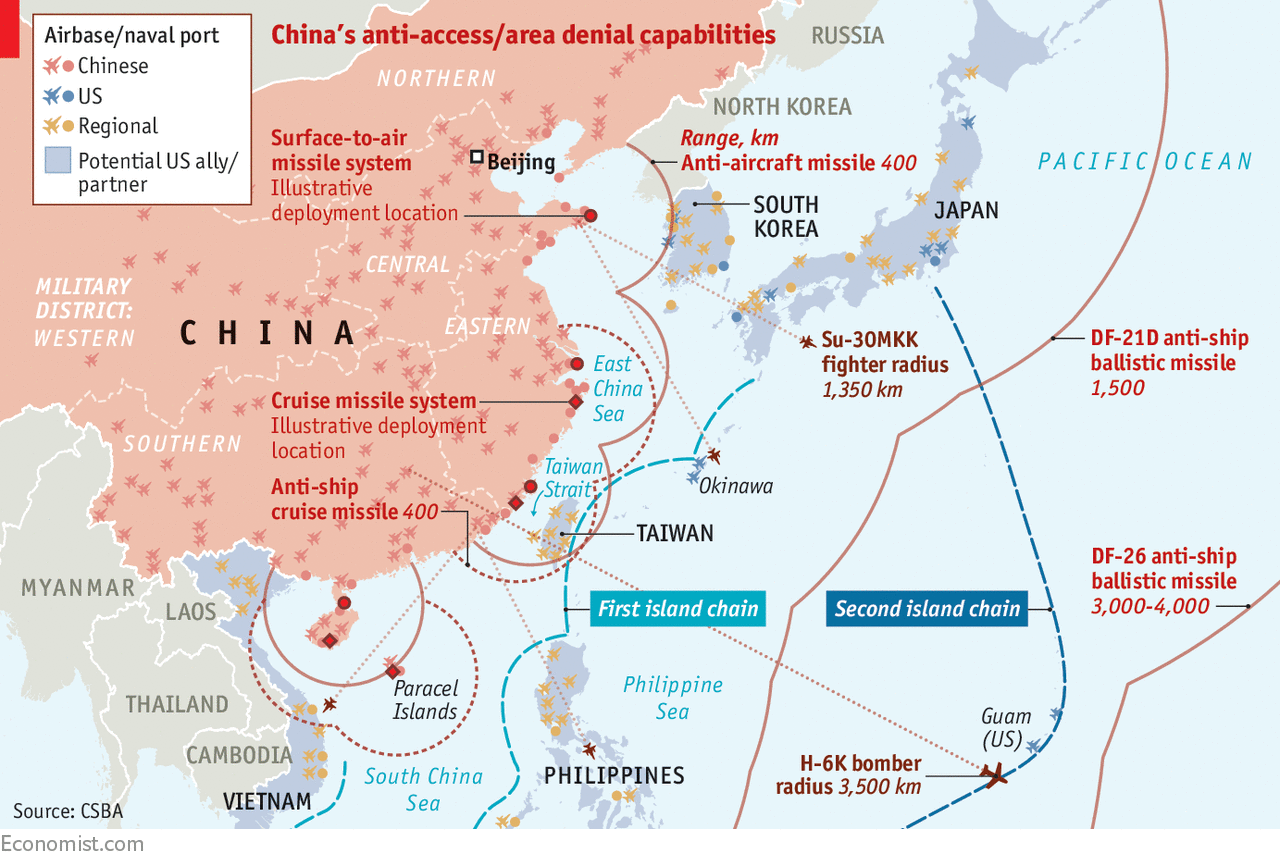

The risk that the West will run into a major conflict with China is lower than with Russia, but it is not negligible and may be growing. China resents the American naval presence in the western Pacific, and particularly the “freedom of navigation” operations that the US Seventh Fleet conducts in the South China Sea to demonstrate that America will not accept any Chinese claims or actions in the region that threaten its core national interests or those of its allies.

The risk that the West will run into a major conflict with China is lower than with Russia, but it is not negligible and may be growing. China resents the American naval presence in the western Pacific, and particularly the “freedom of navigation” operations that the US Seventh Fleet conducts in the South China Sea to demonstrate that America will not accept any Chinese claims or actions in the region that threaten its core national interests or those of its allies.

For its part, China is planning to develop its A2/AD capabilities, especially long-range anti-ship missiles and a powerful navy equipped with state-of-the-art surface vessels and a large submarine force. The idea is first to push the US Navy beyond the “first island chain” and ultimately make it too dangerous for it to operate within the “second island chain” (see map). Neither move is imminent, but China has already made a lot of progress. If there were a new crisis over Taiwan, America would no longer send an aircraft-carrier battle group through the Taiwan Strait to show its resolve, as it did in 1996.

How such tensions will play out depends partly on America’s allies. If Japan’s recently re-elected prime minister, Shinzo Abe, succeeds in his ambition to change the country’s pacifist constitution, the Japanese navy is likely to increase its capabilities and more explicitly train to fight alongside its American counterpart. At the same time other, weaker allies such as Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia and Indonesia may conclude that bowing to Chinese military and economic power is a safer bet than hoping for a declining America to fight their corner.

The greatest danger lies in miscalculation through a failure to understand an adversary’s intentions, leading to an unplanned escalation that runs out of control. Competition in the “grey zone” between peace and war requires constant calibration that could all too easily be lost in the heat of the moment.

The greatest danger lies in miscalculation through a failure to understand an adversary’s intentions, leading to an unplanned escalation that runs out of control. Competition in the “grey zone” between peace and war requires constant calibration that could all too easily be lost in the heat of the moment.

This article appeared in the Special report section of the print edition under the headline "Pride and prejudice"

No comments:

Post a Comment