Bottom Line: A spy’s tradecraft must constantly evolve because of the rapid changes of the digital age – especially the tools and skills required to maintain a legend, or cover identity. Virtual recordkeeping, modern surveillance technology and the vast amounts of a person’s background accessible on open-source platforms such as social media are affecting intelligence operatives’ ability to operate covertly overseas.

Bottom Line: A spy’s tradecraft must constantly evolve because of the rapid changes of the digital age – especially the tools and skills required to maintain a legend, or cover identity. Virtual recordkeeping, modern surveillance technology and the vast amounts of a person’s background accessible on open-source platforms such as social media are affecting intelligence operatives’ ability to operate covertly overseas.

Background: One of the most fundamental needs for a spy is their legend, or a well-prepared but made-up or assumed identity, also known as cover. Legends allow intelligence officers unique access into companies, ministries and groups of interest where they can recruit agents, manipulate unwitting insiders, or observe, report and take direct action themselves.

“The key principle is that cover is about looking like someone else. You are pretending to be somebody else, whom you are not. You should know what that person looks like and you have to know how they behave. Then you have to be able to mirror them. If you don’t do that, then you draw scrutiny on yourself.”

Broadly speaking, intelligence officers operate under three forms of cover – diplomatic, official and nonofficial. Diplomatic cover – under which an intelligence officer takes on the face of a diplomat – is likely the most common, as it grants diplomatic immunity as an insurance policy if discovered. Official covers are disclosed to the host governments and those operating under them openly cooperate and liaise directly with intelligence services in allied countries, creating a backchannel for sensitive interactions. Nonofficial cover, also known as deep cover, includes assuming a made-up identity such as a business person or student. Those under nonofficial cover operate without the knowledge of the host government. If caught, they could face severe repercussions.

During the Cold War, Soviet spies seeking to enter the West would often assume a cover that was built upon someone who had died at a young age. Back in the days of paper recordkeeping, following up on such a background cover required extensive physical research and interviews. The complexity of maintaining a cover often depended on the scrutiny an intelligence officer thought it would receive. In the old days, spies operating under cover could simply create a fake business entity or association with a particular organization, and someone who wanted to follow up on them would call and validate their identity. Perhaps the intelligence official expected someone would drive by the listed street address or walk in and make an inquiry.

From a counterintelligence standpoint, a host country, such as the United States, might immediately evaluate new foreign embassy staff members to determine whether they are intelligence officers or genuine diplomats. Diplomatic positions such as a “passport control manager” or “cultural attaché” may very well be filled with intelligence officers. Even those operating under diplomatic cover, though, can be historically parsed from actual diplomats.

Mark Kelton, former Deputy Director for Counterintelligence, CIA

“If officer X comes into an embassy, you ask: what did his predecessor do; what do we know about his predecessor; is that a position that is traditionally occupied by an intelligence officer or is it traditionally occupied by a real diplomat? Then you look individually at the person. What do we know about this person’s background and is it consistent?”

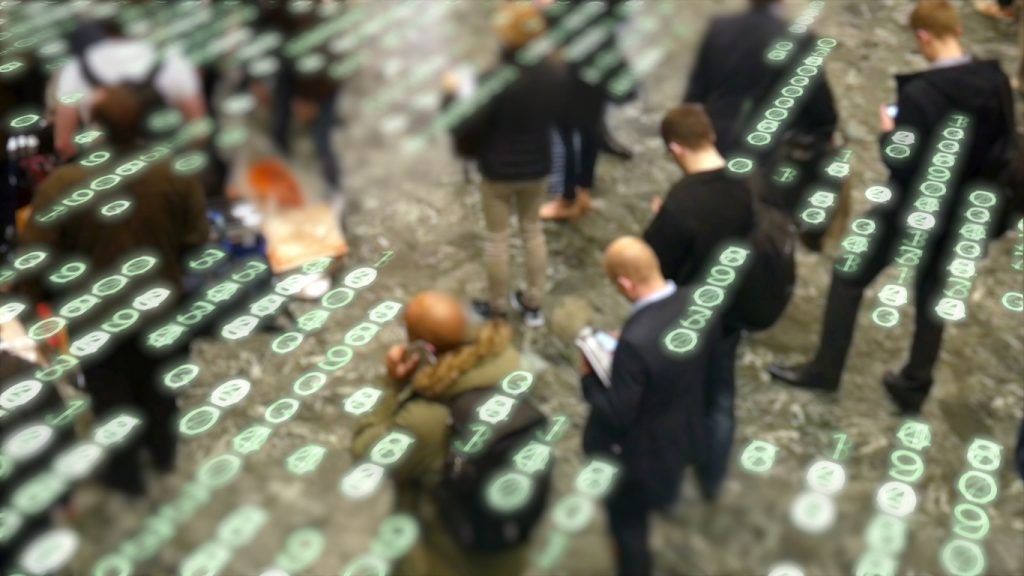

Issue: Technological advances now allow extensive recordkeeping of peoples’ lives through social media, as well as identity verification at borders with biometrics. At the same time, the complete absence of a detailed social media presence can be a red flag, causing counterintelligence investigators to scrutinize individuals further.

Matt Devost, former special advisor, U.S. Department of Defense

“It could be something as simple as a camera that is capturing your face, doing the facial recognition, comparing that against other sources for identity information, up to and including social media. You now have a lot of public access to records associated with corporations and employees, such as LinkedIn. I can be scraping LinkedIn all the time, and if you said you have worked at that job for two years, but your LinkedIn profile just showed up last week, that creates a red flag for me. So you have all of these challenges associated with the aggregation of information alongside the advances in technology that allow for the facial recognition – not only the capture, but the actual correlation piece of it – and the ever-presence of social media.”

Traditional models of joining an intelligence agency and then creating a cover background for a new intelligence officer are raught with potential vulnerabilities. An intelligence officer’s presence on social media must be consistent with their cover and cannot be subject to historical revision. This means those operating under cover have to be thinking about this as a long-term strategy, whereas in the past this process was maybe seen as more short-term. Once recruits join an intelligence service, they will likely have to seamlessly blend their previous social media presence into their new role. Intelligence agencies may already be building social media profiles for future officers to assume when they join in a decade.

While many intelligence officers could simply sync their legends to their online presence – essentially acting normal by hiding in plain sight – failures in other areas of tradecraft could spark suspicion, and retroactive analysis can now be relatively comprehensive. Take, for example, the 2010 Israeli assassination of the high-ranking Hamas member Mohmoud Al-Mabhouh in Dubai, whose body was discovered in his hotel room. The discovery prompted aninvestigation that was able to identify the Mossad officers through hundreds of hours of surveillance footage cross-referenced with airport and hotel registries, phone records, and other sources of information. The entire operation was posted in a video on YouTube for the world to see, and their covers were blown.

Another example of poor tradecraft exposing networks of intelligence officers can be found following the reported CIA’s 2003 operation to abduct an Egyptian cleric known as Abu Omar in Milan and take him to Egypt for interrogation. Warrants for the arrest of 23 Americans – all but one of them identified by the Italian prosecution as CIA officers – were issued in 2005 after tracking their extensive cellphone records that allowed Italian police to determine their movements and link them together.

While mistakes – or even just border-crossings – can draw attention and trigger retroactive analysis of an intelligence officer’s background, advances in data analytic tools could also reveal them in the background noise. Similar to how social media companies are designing algorithms for finding those susceptible to radicalization, systems can be designed to recognize patterns of an intelligence officer’s digital footprint by comparing them with the patterns of spies already known.

Mark Kelton, former Deputy Director for Counterintelligence, CIA

“Young people today are out on the internet all the time and most people have a social media presence. If they don’t, then you ask why and look at the nature of that presence – who are they in touch with, what are they doing, is it something they actively keep up, or is it something that sits dormant, why would it sit dormant? All of those questions come to mind.”

“The commonalities for the operations that have been exposed are tradecraft errors and those who were involved in those operations probably were not as cognizant as they should have been of the technology that could be deployed against them. That is part of understanding the new battlespace. Hostile intelligence services focus on our social media. They have to pick and choose whose social media on which to focus but if they suspect someone of being an intelligence officer or a person of interest worth tracking, then they are going to dissect their social media.”

Response: Ultimately, an intelligence officer’s online presence, much like that in the physical world, must reflect a person who is historically and actively living the life they present themselves as living. While the underlying principles of tradecraft might remain the same, this requires a change in mindset – where it was common to keep a low profile, it now might be required to have a prominent and public online persona like so many others.

“Essentially, is their online presence something that reflects a person that is actively living a life they present themselves as living? Social media is a living thing, and some of it is private, but a lot of it is public too. You are engaged with people all the time. Intelligence officers don’t traditionally do that. So, the challenge is to adapt intelligence activities to the modern social media world.”

“Things like that and some pocket litter or business cards might have been enough many years ago. They still matter, but in today’s world you need the right kind of social media profile.”

“There are some arguing that intelligence officials should not be on social media at all. I think that raises more red flags as it becomes the anomaly. As long as you have a legend that is historically consistent, you can maintain your cover. It is possible if you have no red flags such as a deviation, rewrite, or inconsistency with your history. This means you have to be thinking about this as a long-term strategy, whereas in the past this process was maybe seen as more short-term. Now it requires thinking, if this person is going to be operating overseas, how do we make sure we have resiliency in any of these activities on social media and any of the information they are filling out as a government employee? All of that stuff needs to be consistent because it is subject to retroactive analysis.”

Anticipation: Not only does this create a problem for intelligence officers operating overseas, but it also creates a counterintelligence problem for the United States. By observing someone’s online presence, foreign intelligence services can also seek to determine whether a person of interest might be vulnerable to a recruitment pitch. Another problem intelligence officers will now encounter is doxing – when an adversary reveals a spy’s real identity to the public – news that quickly spreads now via social media, embarrassing the spy’s government and possibly endangering the spy.

Outing spooks has always been a strategic opportunity for foreign governments and others. For example, Philip Agree, a former CIA officer, published the names of CIA case officers in his book and the magazine CounterSpy, potentially leading to the assassinations of some of those revealed. This prompted Congress to pass the 1982 U.S. Intelligence Identities Protection Act, making it illegal to expose the identities of covert agents.

In the age of social media, published identities of those working for intelligence – such as those found in theleaks by the suspected Russian-affiliated Shadow Brokers or in the lists of names released by an ISIS-affiliated hacking group – reach much broader audiences. The goals of releasing this personal information include: discrediting individuals and making it harder to do their jobs; striking a blow to workforce morale and undermining recruitment; publicly shaming the U.S. for conducting operations it often criticizes other countries for; and most damaging, inspiring violence or retaliation against intelligence officers.

Daniel Hoffman, former CIA Chief of Station

“Today our enemies are using the same sort of strategy, but with different tactics – using wildly asymmetric cyberspace for delivery that carries a lot more force compared to Philip Agee’s book.”

Matt Devost, former special advisor, U.S. Department of Defense

“We in the U.S. are very vocal about putting sanctions on, and filing charges against, espionage actors. But if a foreign government is able to catch, name and shame U.S. intelligence employees that are engaging in the same kind of behaviors against different types of targets, it diminishes the U.S. diplomatic argument with some of these other countries. There is a public relations aspect to it. It also creates a safety and distraction risk. It can scare you and make your work less appealing. It can cause your colleagues who weren’t named to be concerned that they are next. So even if it is a minuscule potential for actual physical harm as a result of the documents being released, there is still that psychological impact. Another aspect of it is that they may be aspirational, thinking that maybe there are a few people who will get ahold of that information and go cause problems – maybe not manifesting itself in the physical realm, but rather identity theft or the identification of additional information.”

Mark Kelton, former Deputy Director for Counterintelligence, CIA

“As an intelligence officer – particularly one operating under a cover identity – you are never not working. Never. So, you step through that door, and there is a different world where your life is that work. But that does not mean you don’t have a life when you are living in that world. Intelligence officers have families; they have all of those things. It is just that everything you do takes place within the context of that activity, of that work… That does not mean that you don’t have a life and can’t live a life, and that life can’t be consistent with what you are trying to do. In fact, it can help you greatly to live a life because you want to look normal. You want to look as normal as you can, because the adversary will scrutinize you.”

Levi Maxey is a cyber and technology analyst at The Cipher Brief. Follow him on Twitter @lemax13.

No comments:

Post a Comment