By Jaïr van der Lijn for Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI)

Jaïr van der Lijn argues there is a growing consensus that peace operations have a role to play in preventing and combating organized crime, particularly in weak or collapsed states. So what potential opportunities are there for the further involvement of peace operations in combating organized crime? What negative consequences could such engagement have for the regular actives of peace operations? And how can peace operations ensure effective cooperation and coordination in their efforts to address organized crime. In this article, van der Lijn tackles these questions and more.

Jaïr van der Lijn argues there is a growing consensus that peace operations have a role to play in preventing and combating organized crime, particularly in weak or collapsed states. So what potential opportunities are there for the further involvement of peace operations in combating organized crime? What negative consequences could such engagement have for the regular actives of peace operations? And how can peace operations ensure effective cooperation and coordination in their efforts to address organized crime. In this article, van der Lijn tackles these questions and more.

This article was originally published by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) in February 2018.

I. Introduction

Multilateral peace operations are increasingly confronting a set of interrelated and mutually reinforcing security challenges that are relatively new to them, that do not respect borders, and that have causes and effects which cut right across the international security, peacebuilding and development agendas.1 Organized crime provides one of the most prominent examples of these ‘non-traditional’ security challenges.2

There are many different definitions of organized crime depending on the context, sector and organization. The United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime defines an ‘organized criminal group’ as ‘a structured group of three or more persons, existing for a period of time and acting in concert with the aim of committing one or more serious crimes or offences . . . in order to obtain, directly or indirectly, a financial or other material benefit’.3 However, this definition is not unchallenged. The labelling of what is legal and illegal, or legitimate and illegitimate, is done by state actors, and as this is a normative decision, the definition privileges the state. Particularly in conflict settings in which state governance is weak, corrupt or contested, the binary choice of good versus bad is arbitrary and often does not reflect the views of the population. In fact, by labelling actors as organized criminal groups, potential partners in peace processes may be pushed towards becoming spoilers instead.4

The role of organized crime in armed conflict and its relationship with multilateral peace operations has clearly varied in different contexts. When organized crime has supported spoilers to peace processes, the distinction between crime and conflict is blurred. Its support may be in competition with the state in order to continue an insurgency, for example, the Taliban and Haqqani networks taxing the opium narco-economy in Afghanistan. It may also sustain warlords in creating their own proto-states as an alternative to a strong overall state, such as in Afghanistan and Somalia. In other contexts, organized crime may evade the presence of the state, settle in regions where the state is absent and exploit the void with its own armed groups to exploit natural resources. Countries such as the Central African Republic (CAR), Côte d’Ivoire, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Liberia and Sierra Leone have seen their natural resources plundered, including coltan, diamonds, gold and timber. In Haiti, for example, drug traders have also teamed up with gangs to benefit from the absence of the state.

In another role, organized crime may be a partner of peace operations because it has gained access to or control over the host government. Some criminals may have continued their criminal activities within government, for example, in Kosovo, where addressing them is difficult as they are considered war heroes. In other cases, organized crime may have virtually captured the state, such as reportedly in Guinea-Bissau, and control the sovereign government of a country. In extreme cases, peace operations have inadvertently supported organized crime either by engaging in illicit trade or activities or by increasing the demand for such goods or activities.

Thus, organized crime may have a predatory relationship with the state when it is in violent competition, but it may also coexist with the state in a parasitic or symbiotic relationship—depending on whether or not it is targeting state resources. The challenges of organized crime may, therefore, be of direct or indirect relevance to multilateral peace operations. Directly, it may behave as a spoiler or evade peace processes. Indirectly, it may decrease the effectiveness of peace operations, particularly long term, contributing to the continued fragility of countries and their peace processes in its role as partner.5

II. Peace operations and combating organized crime

In 2009 the UN Security Council noted its increasing concern regarding drug trafficking and transnational organized crime as threats against international peace and security, and requested that the UN Secretary-General mainstreams these issues as factors in conflict prevention, peacekeeping and peacebuilding activities.6 The Secretary-General subsequently acknowledged that this needed to be done by focusing on the positive contribution of justice and the rule of law, within the ‘one UN’ approach.7

Multilateral peace operations have used both co-optive and coercive tactics, working with and against organized crime groups respectively, and it appears that different contexts require different approaches. For example, predatory groups are less likely to be co-opted and therefore often require solutions of a more law-enforcement type. Co-optation may work as an approach for dealing with symbiotic and parasitic groups in the short term. However, if not part of a transitional or transformational strategy—either by eradicating groups or inserting them into the licit system—co-optation may have negative effects in the long term, as the stability it produces might be mistaken for peace. Therefore, a sequenced transitional strategy in which organized crime groups are slowly inserted in the legitimate system is often seen as the best solution.8

Preventing and combating organized crime

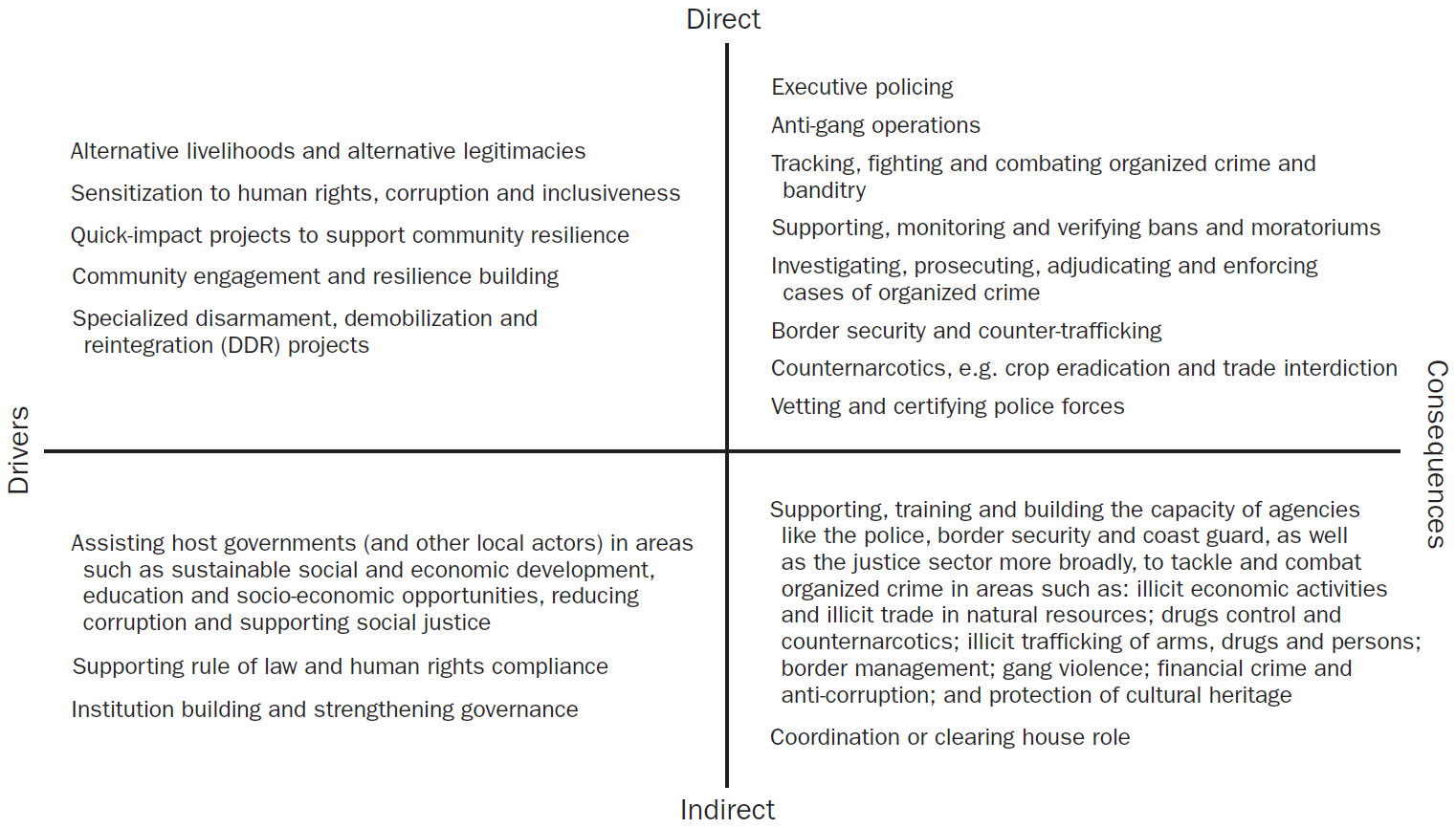

When considering ways of preventing or combating organized crime, it is possible to organize the spectrum of multilateral peace operation activities along two dimensions. First, activities can target the consequences or drivers of organized crime. Activities that target consequences (or symptoms) are mainly reactive, as they respond to a threat that has already been identified with the objective of reducing or neutralizing it. Activities that aim to target drivers (or root causes) are proactive, in the sense that they seek to prevent organized crime by addressing the push and pull factors that might produce or enable it. Second, activities can target these consequences and drivers directly or indirectly. Whereas direct activities are executed by peace operations themselves, indirect activities aim to build or strengthen the capacity of the host government—or local non-state actors at the civil society or community level—to prevent and combat organized crime, including by addressing its root causes.

Together, these two organizing principles result in four broad categories of activities that multilateral peace operations could undertake to address organized crime (see figure 1). This scheme is a simplification and some activities may not fit perfectly into one category or they may overlap. The advantage of this categorization, however, is that it can facilitate and structure further discussion by focusing on concrete activities.

Figure 1. Examples of activities that multilateral peace operations could undertake to prevent or combat organized crime. Notes: The activities included have been identified by the author in peace operation mandates or selected from examples in literature. Activities are not unique to one category and can overlap.

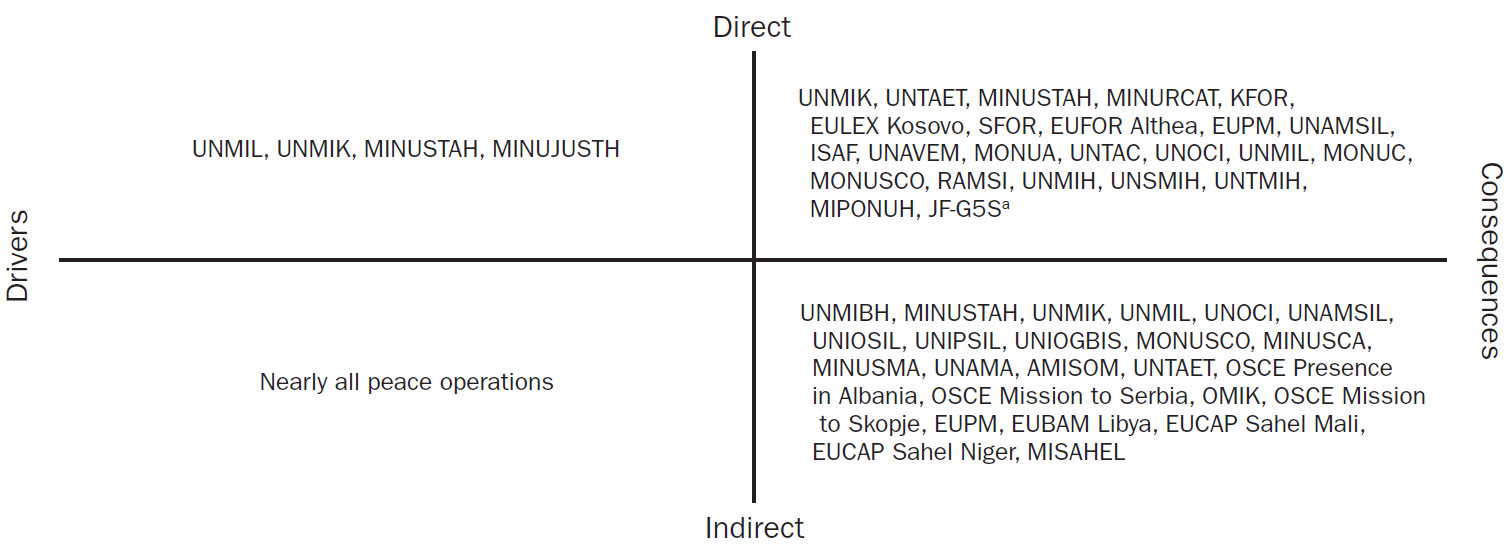

III. Examples of peace operations that have engaged in combating organized crime

References to organized crime are frequent in UN Security Council resolutions and other documents mandating multilateral peace operations, yet only a few operations have been explicitly tasked with addressing it (see figure 2). A number of multilateral peace operations have undertaken activities that address the consequences or drivers of organized crime, both directly and indirectly, as tasked by or within the policy space of their mandate. However, multilateral peace operations in general do not do so in a systematic manner and they have primarily focused on the consequences. Often these efforts have broader objectives that might deliberately or incidentally overlap with combating organized crime goals. Therefore, having a strong and specific mandate on organized crime does not guarantee that missions are able to undertake a lot of work in that area, while not having such a mandate does not prevent them from becoming heavily involved. Moreover, peace operations actually run the risk of stimulating organized crime, as their personnel can attract prostitution and encourage black market trading in items such as cigarettes.9

Activities addressing the consequences of organized crime

A number of UN and non-UN peace operations have dealt with the consequences of organized crime directly, at times by taking on executive policing and law enforcement tasks. Within their transitional authority mandates, the UN Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK) and the UN Transitional Administration in East Timor (UNTAET) effectively substituted local police forces and enforced law. In other cases, the UN did not substitute the national police, but tracked and fought organized crime alongside it.10 A few missions also vetted and certified police forces to eliminate criminal elements.11 The UN Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH) had a robust mandate to ‘tackle the risk of a resurgence in gang violence’ while it also engaged in border management and counter-trafficking tasks, as did missions in Kosovo, Bosnia-Herzegovina and Sierra Leone.12 UN peace operations in Angola, Cambodia, Côte d’Ivoire, the DRC, Liberia and Sierra Leone, and the African Union (AU) Mission in Somalia (AMISOM), have also supported, monitored and verified bans and moratoriums on conflict resources, such as diamonds, timber and charcoal.13

Although often ‘reluctantly, unsystematically and belatedly’, military forces, such as the Kosovo Force (KFOR), the Stabilization Force (SFOR) and the European Union (EU) Force in Bosnia and Herzegovina (EUFOR Althea), have also participated in such law enforcement tasks, particularly during policing vacuums before the deployment of, or during the transition between different, policing missions.14 Additionally, in Afghanistan the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) engaged in counternarcotics activities. Initially its role was to facilitate eradication and interdiction by the Afghan institutions and security forces, but later it also actively targeted insurgency-related opium storages, heroin laboratories and drug traders.15

A number of missions, such as UNMIK, the EU Rule of Law Mission in Kosovo (EULEX Kosovo) and the Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands (RAMSI), have also engaged directly further up the criminal justice chain. UNMIK and EULEX Kosovo have been tasked with ensuring that crimes are investigated, prosecuted, adjudicated and enforced, and they have received the power to do so in cooperation with Kosovan investigators, prosecutors and judges, but also independently if needed. EULEX Kosovo, in particular, has a strong focus on organized crime, corruption, fraud and other serious criminal offences.16 Likewise, RAMSI added investigative, detention and judicial officers to the existing capacity on the Solomon Islands, in part to deal with organized crime.17

Figure 2. Examples of multilateral peace operations that have undertaken activities to prevent or combat organized crime. AMISOM = African Union Mission in Somalia; EUBAM Libya = European Union Border Assistance Mission to Libya; EUCAP Sahel Mali = EU CSDP Mission in Mali; EUCAP Sahel Niger = EU CSDP Mission in Niger; EUFOR Althea = EU Force in Bosnia and Herzegovina; EULEX Kosovo = EU Rule of Law Mission in Kosovo; EUPM = EU Police Mission; ISAF = International Security Assistance Force; JF-G5S = Joint Force of the Group of Five Sahel; KFOR = Kosovo Force; MINUJUSTH = UN Mission for Justice Support in Haiti; MINURCAT = United Nations Mission in the Central African Republic and Chad; MINUSCA = UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in the Central African Republic; MINUSMA = UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali; MINUSTAH = UN Stabilization Mission in Haiti; MIPONUH = UN Civilian Police Mission in Haiti; MISAHEL = AU Mission for Mali and the Sahel; MONUA = UN Observer Mission in Angola; MONUC = UN Organization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo; MONUSCO = UN Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo; OMIK = OSCE Mission in Kosovo; RAMSI = Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands; SFOR = Stabilisation Force; UNAMA = UN Assistance Mission in Afghanistan; UNAMSIL = UN Mission in Sierra Leone; UNAVEM = UN Angola Verification Mission; UNIOGBIS = UN Integrated Peacebuilding Office in Guinea-Bissau; UNIOSIL = UN Integrated Office in Sierra Leone; UNIPSIL = UN Integrated Peacebuilding Office in Sierra Leone; UNMIBH = UN Mission in Bosnia and Herzegovina; UNMIH = UN Mission in Haiti; UNMIK = UN Mission in Kosovo; UNMIL = UN Mission in Liberia; UNOCI = UN Operation in Côte d'Ivoire; UNSMIH = UN Support Mission in Haiti; UNTAC = UN Transitional Authority in Cambodia; UNTAET = UN Transitional Administration in East Timor; UNTMIH = UN Transition Mission in Haiti. a Not a multilateral peace operation according to the definition applied by SIPRI.

A broader and increasing variety of military and civilian multilateral peace operations—UN peacekeeping operations, UN special political missions and non-UN operations—has been mandated to resource, train and assist host governments, providing planning and operational support to prevent and combat organized crime within the context of broader rule of law and security mandates. This has established or contributed to the capacity building and training of national law enforcement and other agencies (e.g. border management, coast guards and ministries), as well as the broader criminal justice system, which deal with the following areas: drugs and narcotics; illicit economic activities and illicit trade in natural resources; illicit trafficking of arms, drugs and persons; gang violence; financial crime and anti-corruption; kidnapping; destruction of cultural heritage; and transnational crime and organized crime in general. EU missions have often focused specifically on the niche of training and capacity building. Peace operations have also played clearing house roles by supporting the exchange of information and they have coordinated international efforts.18

Activities addressing the drivers of organized crime

Only a limited number of multilateral peace operations have dealt directly with the diverse drivers of organized crime. In general, these tasks seem to be left to other organizations or they are ignored. The few tasks implemented by missions focusing directly on addressing these drivers have included UNMIK setting up a campaign in 2005 called ‘not for sale’, against human trafficking in Kosovo. Another example is the reopening of the disarmament, demobilization and reintegration (DDR) process by the UN Mission in Liberia (UNMIL) and MINUSTAH’s specialized DDR programmes for gangs in Haiti. In both cases, there were projects aimed at providing training and job opportunities to actors involved in organized crime.19 Furthermore, in Haiti corruption within the Haitian National Police had fed the population’s distrust of the police, stimulating their reliance on gangs and other armed groups for protection. Therefore, addressing police corruption meant, in part, taking away some of the drivers for popular gang support.20 MINUSTAH and the UN Mission for Justice Support in Haiti (MINUJUSTH) have also implemented short-term, quick-impact projects to increase community resilience against gangs and organized crime and to draw the population away from gang protection. However, projects directly addressing the drivers of organized crime such as these have been exceptional, and they have never aimed for long-term economic transformation.21

Nonetheless, almost all multilateral peace operations have dealt with the drivers of organized crime indirectly, considering that they aim to address instability and conflict. Mission activities often have broader objectives that deliberately or incidentally overlap with preventing and combating organized crime. Peace operations have addressed issues such as corruption, development, human rights, rule of law and social justice, and have supported discussions on these topics in the media of host nations.22

IV. Peace operations, combating organized crime: potential implications

The debate on whether multilateral peace operations can or should more actively address organized crime remains divided between sceptics who are wary of the challenges and costs, and advocates who see this as an opportunity—or, indeed, a necessity—to preserve the relevance of peace operations.23 Recent discussions on the potential opportunities and challenges have focused primarily on UN peace operations, for which activities related to organized crime are a relative novelty and a clear step beyond their traditional aims and tasks.

Opportunities for the involvement of peace operations in combating organized crime

Organized crime has become more globalized and is a challenge in many of the theatres where multilateral missions have been deployed. Organized criminal groups can be spoilers in peace processes, as their illicit activities thrive in unstable environments, while political groups (state or non-state) may set up illicit conflict economies in order to continue fighting. In addition to instrumentalizing disorder, organized crime may also criminalize politics and make state fragility pervasive. Consequently, it is argued that organized crime can no longer be ignored by peace operations—a failure to understand it might undermine international efforts to build peace, security and the rule of law.24

If organized crime is dealt with early on, it may prevent the empowerment of criminal groups. The longer such groups are left untouched, the better able they are to entrench themselves and eventually even to criminalize the state. Bosnia-Herzegovina and Kosovo are often given as examples of places where missions allowed this to happen, by initially not wanting to pursue the ‘war heroes’ and offset the relative stability.25 Preventing a state from being ‘hollowed out’ by organized crime makes it less vulnerable to state collapse and coup d’états, which would otherwise require further international intervention. Moreover, as organized crime is often transnational, dealing with it can ensure stability in wider regions.26

Dealing with organized crime also increases public faith in multilateral peace operations and any state institutions they support—they may be perceived as taking on the problems that really matter to the local population. This becomes particularly important in an environment in which, as a result of the presence of a multilateral peace operation, organized crime is already able to benefit from, for example, hard currency flowing into the economy and other unwitting effects of missions and personnel potentially being involved in criminal activities.

Furthermore, taking on organized crime makes multilateral peace operations more relevant to international actors as they deal with issues that matter to them. For example, the focus of UN operations on the nexus between terrorism and organized crime helped the United States under President Barrack Obama to see their relevance to its own interests.27 Those who argue that peace operations should engage in preventing and combating organized crime tasks, however, generally believe that missions should not do so on their own, but in close collaboration with other actors, particularly the host government, and within a broader international strategy.28

Potential challenges of involvement in combating organized crime

Despite the opportunities above, there are concerns that increased engagement by multilateral peace operations in preventing and combating organized crime could have unintended consequences for their regular activities, as well as for broader efforts to address peace and security more generally. A number of potential challenges and risks are frequently mentioned in this regard.

First, countries such as China and a number of Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) members fear that by internationalizing the issue of organized crime, sovereignty may be compromised. Investigative and prosecutorial powers are traditionally seen as part of the essence of sovereignty and part of the state monopoly on the use of force. Therefore, many countries prefer to engage with organized crime at a national level. These challenges have been directly transplanted into peace operations, which operate on the basis of the host government’s consent. As such, when representatives of host governments or their armed forces have been implicated in organized crime, such as in Guinea Bissau and eastern DRC, consent cannot be assumed. Organized criminal groups with government connections have used sovereignty to shield off external intervention, while they have also used international interventions to deal with competitors.29

Second, multilateral peace operations might not be the most suitable tool to deal with the challenge, and specialized organizations may have more relevant expertise. Making missions responsible for dealing with organized crime might not be realistic given their already overly ambitious mandates and limited resources. Combating organized crime requires police forces and capabilities which most organizations that deploy peace operations (e.g. the UN) do not have sufficiently at their disposal. Neither are governments often prepared to provide them, unless a clear national security interest is at stake. Likewise, given the international character of organized crime, missions lack the human, financial and technical resources to comprehensively address organized crime, as this would require operations beyond the territory of the host nation. The short-term presence of peace operations and the frequent rotation of civilian and uniformed personnel also mean limited long-term commitment.30

Third, working against organized crime may have trade-offs, for example, when an important interlocutor for an operation is engaged in illegal activities. Particularly in the early stages of a peace process, when stability is still fragile, dealing with organized crime is often a low priority. In fact, the topic is often avoided altogether for the sake of short-term political expediency and deliverables, because otherwise the government and other parties involved might have to be held accountable. In some cases, organized crime may even have a positive impact on peacebuilding processes and function as a partner to peace operations. Organized criminal groups may be service providers to parts of the population and possess local, grass roots legitimacy. They may stimulate intercommunal trade and interaction and, as such, integrate the economies of former adversaries. Moreover, working against organized crime may ultimately affect the security of peace operations personnel, and so senior officials in peace operations tend to avoid targeting organized criminal groups.31

Fourth, by focusing on organized crime, complex challenges risk being reduced to law enforcement problems between the host nation and ‘criminal’ actors. Consequently, the underlying causes may be ignored, such as insufficient inclusive governance and limited economic development, while the law enforcement interventions only work to further alienate intractable actors. An approach which does not address the broader political economy and underlying factors enabling crime also runs the risk of supporting and leaving behind a security apparatus that does not fight crime, but profits from it.32

Fifth, the involvement of the military in fighting crime within peace operations brings with it challenges. There is the risk of blurring the division of labour between the military and the police. If there is a policing gap, this is often filled by gendarmerie units and SWAT teams, such as in Haiti and Kosovo. Including combating organized crime can, therefore, undermine a central principle of security sector reform. Moreover, examples such as Kosovo and Bosnia-Herzegovina have shown that the military generally does not have the right training, equipment or expertise to deal with organized crime. This has resulted in investigations and prosecutions being hampered because crime scenes were not preserved and evidence was not secured.33

Sixth, when combating organized crime is included in the context of peace operations and ‘outsourced’ to international actors, it is often done in a largely unaccountable manner. Democratic control over such activities is complicated by weak institutions in the host nation and limited oversight of the mission and its personnel. In Kosovo this led to a number of incidents, for example, KFOR reportedly detained 1800 persons at a US camp in the absence of a functioning legal system and with only limited official access.34

Seventh, although combating organized crime in peace operations is generally presented as a noble cause, it is also used to legitimize the use of funds and resources to audiences in finance-contributing countries. This change of perspective—away from host populations—may affect the focus of peace operations on the ground. Rather than solving the problems of host nations, operations may prefer to deal with the challenges that are most relevant to external actors.35

V. Cooperation and coordination

Effective cooperation and coordination is a major challenge in all multi-stakeholder efforts in the field of peace and security. The need to improve cooperation and coordination within organizations and missions, and with other relevant actors including other peace operations, receives recurring attention in mandates, policy documents and strategies. Since multilateral peace operations are relative newcomers to the field of preventing and combating organized crime, it is important to consider the opportunities and challenges for effective cooperation and coordination presented by their actual and potential activities in this area.

Cooperation and coordination between and within peace operations

Cooperation and coordination between the different components of a multilateral peace operation are essential in preventing and combating organized crime. A technical approach that only deals with law enforcement, for example, is not enough given the frequently claimed nexus of organized crime, armed conflict and violent extremism. A comprehensive or integrated approach is required that also deals with strengthening governance, the legitimacy of the government and social cohesion, and that stimulates social and economic inclusivity and development.36

MINUSTAH is a good example of a mission in which the military and civilian parts cooperated together in fighting gang violence in intelligence-led operations. The Joint Missions Analysis Centre (JMAC), working extensively with local informants, collaborated with Brazilian, Chilean and Uruguayan military contingents to gather the required information for the Haitian National Police, and MINUSTAH formed police units to conduct operations against gangs and their leaders. This was primarily possible because deteriorating gang violence required urgent action, regional troop contributors were willing to act, and the mission’s leadership was in favour of a proactive response. In many other missions, cooperation and coordination between different units and contingents has been difficult, particularly in the field of intelligence sharing.37

Cooperation and coordination is also important between different multilateral peace operations. Modern mission environments often host multiple operations in complex constellations, both in parallel and in sequence. Missions that are deployed in parallel usually cooperate in various ways and have both formal and informal mechanisms in place to coordinate their activities. However, recent experiences have demonstrated that there are challenges to an effective division of labour among the various peace operation actors, and to their cooperation and coordination.

First, having a comprehensive and sustainable approach to organized crime in such multi-mission environments is difficult. Preventing and combating organized crime demands all the different parts of the judicial chain to cooperate within one approach. Moreover, the judicial dimension is only one aspect, and addressing the broader political economy and underlying factors enabling crime is also required. Within complex constellations of missions, coordination problems are often combined with the absence of a systematic strategic approach and together they have a negative effect on mission effectiveness. Different organizations, or even different contingents, using different approaches that do not sufficiently link up with those used by others, risk becoming a ramshackle body of incongruent systems and outcomes.38

Second, turf battles are common. In Kosovo, for example, UNMIK and EULEX Kosovo saw KFOR’s Multinational Specialized Units (gendarmerie) as a redundant force and it has been argued that they encroached on civilian policing tasks without coordinating with those actors primarily responsible for policing.39

Third, the different approaches and perspectives of organizations deploying peace operations are amplified by the geopolitics of countries and regions. In Kosovo the cooperation and cohesion of efforts between UNMIK, KFOR, OMIK and EULEX Kosovo were impeded by the power politics of the USA, the EU and Russia, which were played out in and between these organizations.40 In Africa, in peace operations such as in the CAR, Mali and Guinea-Bissau, there has been frequent disagreement between the Regional Economic Communities, the AU, the EU and the UN over the concept of subsidiarity and whose interests and approaches should be leading the work.41

Fourth, the deployment of parallel military and civilian peace operations may create obstacles when a predominantly military operation is given public security tasks. As discussed above, the organized crime efforts of KFOR have been perceived as disjointed and ad hoc. Even if some gendarmerie units were effective, they were not part of a coherent international structure and faced a weak criminal justice system.42

Fifth, intelligence sharing between missions is a challenge. Again, Kosovo is a good example, where KFOR was often unwilling to share intelligence with UNMIK. This impeded cooperation between the missions and resulted in errors such as KFOR raiding brothels that were also being monitored by UNMIK.43

Sixth, and finally, the handover from one mission to another needs further regulation. Follow-up missions often complain that precursor missions are not forthcoming enough, while precursor missions often see follow-up missions as too demanding, with the consequence that handovers can be ineffective or incomplete. For example, in the case of the handover from UNMIK to EULEX Kosovo, a lot of criminal cases were dropped following the transition, as records and documents were lost or incomplete.44

Cooperation and coordination between peace operations and other actors

As multilateral peace operations assume a larger role in addressing organized crime, they join a multitude of other actors that are already involved at international, regional, national and local levels. The responsibilities are currently dispersed—and to varying extents duplicated— across multiple entities in multilateral organizations and governments, as well as across different domains, such as security, development and economy. Preventing and combating organized crime also requires engagement with civil society, notably local communities, women and youth. Therefore, peace operations have to coordinate potential activities with all these different stakeholders in order to ensure their coherence and effectiveness.

In recent years international coordination and cooperation between peace operations and other stakeholders, while limited, has intensified, although resistance remains from those who are against peace operations venturing too far into combating organized crime. The UN’s role is often seen as that of coordinator and provider of technical assistance. The years 2010–12 were a turning point in international cooperation. The UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) started to cooperate with the UN Department of Political Affairs in an internal Task Force on Drug Trafficking and Organized Crime, and with the UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations (UNDPKO) following a joint plan of action to strengthen their cooperation in conflict and post-conflict areas.45 The Global Focal Point (GFP) was set up, bringing together the Office of Rule of Law and Security Institutions (OROLSI) and the UN Development Programme (UNDP), to form a ‘one-stop shop for rule of law issues’. Lastly, UN police increasingly cooperated with INTERPOL and UNODC for the collection and analysis of police intelligence.46

However, cooperation and coordination with host nations remain the core elements of international cooperation on organized crime. This is particularly challenging if a host government’s institutions are weak, corrupt or not committed to addressing organized crime. Cooperation may become ineffective, as national counterparts try to frustrate operations, or even dangerous, if the state is already corrupted and additional state capacity is built. Nevertheless, any successful effort to deal with organized crime requires national and local ownership and working closely with local actors. Extensive knowledge of the situation on the ground and local support are essential for capacity building and the eventual handover to local counterparts. The example of EULEX Kosovo is particularly telling in this regard. In spite of its sophisticated capabilities, information gathering on the local situation has remained difficult and costly. The limited extent of support for the mission has meant that military escort is often required for arrests, and joint investigations by the mission and the Kosovo Police have been limited due to a lack of trust and understanding.47

As organized crime is generally international in character, a multilateral peace operation dealing with the issue requires a regional or even global approach, and often has to coordinate and cooperate with the governments of neighbouring countries. However, those governments do not always appreciate external coordination, and particularly not when headed by the UN. In the case of MINUSTAH, at times UN staff felt that the USA discouraged or ignored the mission’s efforts in the field of organized crime.48

Although multilateral peace operations are essentially state-centred, they are increasingly trying to pay attention to civil society in a people-centred approach. Thus far, however, they have been less able to implement bottom-up approaches when it comes to combating organized crime. Nevertheless, the UNDP and the UN Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat) have shown that community resilience against organized crime can be strengthened and that supporting communities through development and governance projects can be effective, for example, by supporting civil society and local governance.49

It is important for multilateral peace operations and security actors, on the one hand, and economic and development actors, on the other hand, to ensure a concerted effort. They often have different perspectives and risk thwarting each other’s work when their two approaches compete. Security actors and peace operations look at organized criminal groups as political and military actors in a state-making process; as potential spoilers or partners that are dealt with in a near-technical processes of coercion, negotiation and containment. Economic and development actors, such as the World Bank and the UNDP, tend to focus on the underlying structural causes that organized crime exploits, for example, high unemployment, poverty, weak institutions and the proliferation of weapons. Such causes require transformation through development programmes focused on macroeconomic reform, institution building and labour programming.50

Lastly, there is room for further cooperation between multilateral peace operations with a rule of law or organized crime mandate and panels of experts (small fact-finding teams appointed to monitor targeted sanctions). They have already coexisted in some countries, for example, Côte d’Ivoire, the DRC, Liberia and Sudan, and the findings and recommendations of such panels of experts have often been relevant to the work of peace operations regarding organized crime and corruption.51

VI. Conclusions

Multilateral peace operations have increasingly undertaken activities that directly and indirectly target the drivers and consequences of organized crime. Research on the topic is still relatively limited and critical criminology perspectives—challenging traditional understandings—are primarily hidden in case study literature. In spite of the challenges, there appears to be a growing consensus that there is a role for peace operations to play in preventing and combating organized crime, particularly in weak or collapsed states. However, there is also a common understanding that missions should only be one of a number of instruments within a broader strategy to tackle organized crime and that the first priority is generally stabilizing the security situation.

Nevertheless, playing this role may have important consequences for multilateral peace operations and requires the following: (a) a geographical refocus away from the host nation’s centre towards border regions, as organized crime thrives primarily in hinterlands and ‘ungoverned spaces’; (b) an intelligence-led and analysis-led approach to ensure that the context of the efforts, particularly the political economy, is well understood and operations are well informed and do not have negative effects; (c) a transnational approach that goes beyond a single host nation and deals with the challenge in a regional manner; (d) an integrated approach in which different organizations cooperate and coordinate all international efforts; and (e) a gradual approach in which preventing and combating organized crime starts as soon as possible, but only after minimal security is established, providing a mission with the operational space to look into other activities.52

No comments:

Post a Comment