By SYDNEY J. FREEDBERG JR.

WASHINGTON: Why are the Marines in love with 3D printing? Like most romances, it starts with the small things, things too small for the conventional supply system to manage, like a two-cent plastic button that preempts a $11,000 repair. Big defense contractors, take notice. “There’s an intercom in most helicopters,” said Gen. Robert Neller, commandant of the Marine Corps. Ground-pounders like him tend to hit the buttons too hard and break them. But the Pentagon supply system doesn’t deal in replacing individual buttons. “You’ve got to buy the whole faceplate of the intercom,” Neller said. “It costs $11,000.”

WASHINGTON: Why are the Marines in love with 3D printing? Like most romances, it starts with the small things, things too small for the conventional supply system to manage, like a two-cent plastic button that preempts a $11,000 repair. Big defense contractors, take notice. “There’s an intercom in most helicopters,” said Gen. Robert Neller, commandant of the Marine Corps. Ground-pounders like him tend to hit the buttons too hard and break them. But the Pentagon supply system doesn’t deal in replacing individual buttons. “You’ve got to buy the whole faceplate of the intercom,” Neller said. “It costs $11,000.”

Recently, Neller met a young corporal with a 3D printer: “Now they can print a button for two cents.”

The only hitch? The parts weren’t approved for installation on an aircraft. “I said, put the button on,” Neller told the National Defense Industrial Association last week. “Print a bag of them and hang them there.”

Neller’s No. 2, Gen. Glenn Walters, has his own longtime love affair with 3D printing. His favorite anecdote is a Marine Corps tank unit that had six 70-ton M1 Abrams tanks idled because of a broken impeller fan needed to clear the air filter. Ordering a single spare fan through the normal system would cost $1,400 and take 18 months. Instead, Walters said, a young female sergeant in the 1st Maintenance Battalion took the initiative to find a contractor “who could 3D print that thing for about $300 dollars and delivered all of them in seven days.”

“My eyes are watering with what our young people can do right now,” Walters told the McAleese/Credit Suisse conference last week. “I have an engineering background, but I’m telling you, some of these 21- and 22-year-olds are well ahead of me.”

“The men and women in uniform, they’re impressing us, they’re really smart and they’ve got a lot of really good ideas,” Neller said. “We would be well served to turn them loose. I saw that at the Innovation Challenge.”

The Marine Corps now systematically cultivates its young innovators with field experiments and what it calls Innovation Challenges. The most recent, on logistics, brought a hundred young Marines from around the Corps to San Diego to work with university students on robotics, energy supplies, and 3D printing. It’s formally known as “additive manufacturing” because it builds parts up one droplet of material at a time, whereas traditional “subtractive” manufacturing starts with a big piece of metal or wood and carves it down.

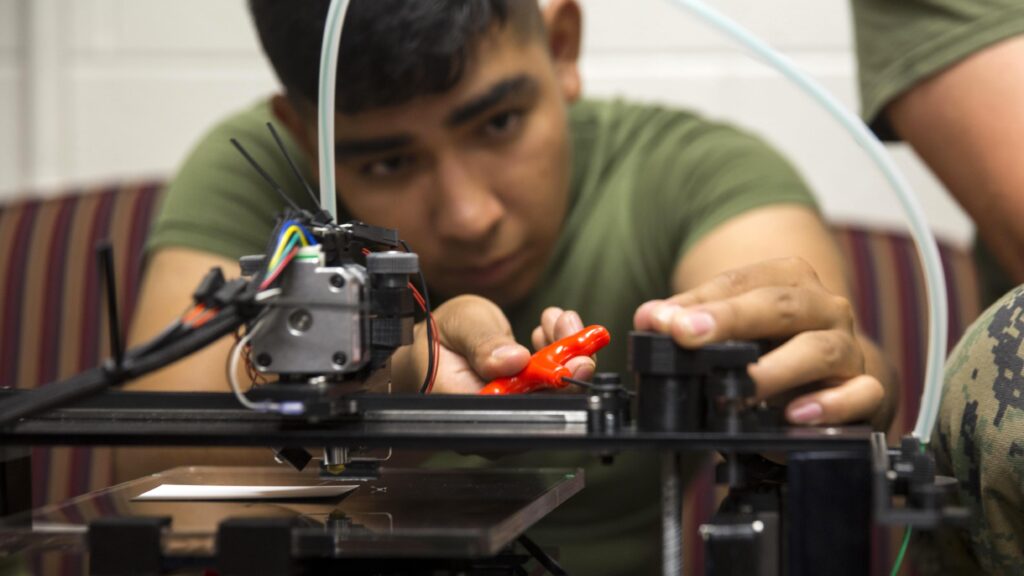

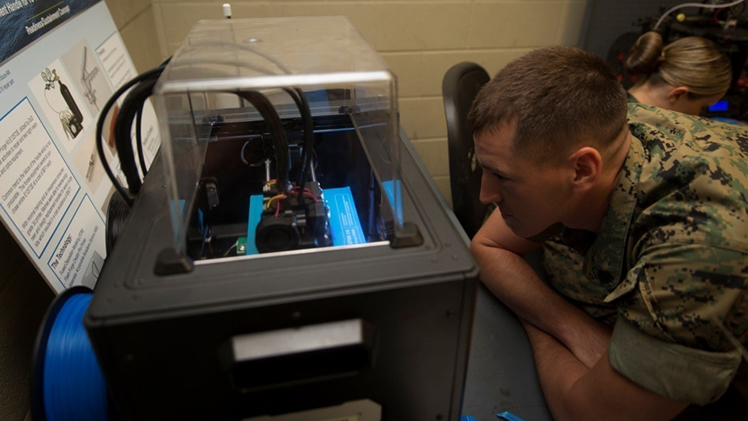

A Marine watches his design take shape on a 3D printer.

Beyond the one-shot challenges, the Marines are also pushing to institutionalize 3D printers in their units. At last count, said Walters, there were 69 printers of various types in maintenance battalions, infantry battalions, and aircraft squadrons — the three main branches of the Corps.

As 3D printing spreads, it is going to change how the Marine Corps contracts for supplies, Neller warned National Defense Industrial Association members. “Many of our vendors use additive manufacturing to build stuff for us, and my question to them is, well, if you can print this … why can’t I just print it?

“I’ll pay you for the tech data,” Neller emphasized. “We were at a meeting with a very senior prime vendor that builds a lot of stuff for a lot of us…. I said, look, you should expect to get paid for the intellectual property, (but) as opposed to buying a parts block or a maintenance plan, I’m going to say, hey, I’ll pay you for the technical data package that comes in a hard drive that I can print.”

Then-Maj. Gen. Glenn “Bluto” Walters smiles at his promotion ceremony in Aghanistan.

Neller and Walters envision a future in which Marine units routinely print many spare parts and small items of equipment on the spot — maybe even the mini-UAVs that Neller is now issuing to every rifle squad. Instead of buying drones out of the procurement accounts, for example, Walters suggested, “these small UAVs, these small things, they need to be more consumable – buy them in O&M (Operations and Maintenance).”

Not every ground unit or Navy ship will have the full complement of specialized printers. Printing metal parts — especially ones rated safe for aircraft — is much more demanding than plastic, for example. Additive manufacturing’s building up of parts layer by layer may not always work well on a tossing, rolling ship. But if a ship needs a part they can’t print for themselves, Neller mused, “we’ll put it on a drone and we’ll fly it over to your ship. Boom. We’re done. No more DHL … No more Bahraini customs.” (That last got rueful laughter).

Why are the Marines so much more visibly enthused about 3D printing than, say, the Army? It’s in part because of personalities: Neller and Walters have seized on the idea. It’s in part because the culture of the Marine Corps, as the smallest and least bureaucratic service, is more receptive to entrusting junior personnel to innovate on their own initiative. And it’s in part because the Marines’ mission scatters them so widely across the world in small units, at the end of long and often precarious supply lines. But as the entire military moves away from big bases like in Iraq to “distributed operations” in multiple domains, the other branches may fall in love with 3D printingtoo.

No comments:

Post a Comment