By Lise Howard and Alexandra Stark

As with most civil wars, the war in Yemen is marked by the influence of outside actors. It began in September 2014, when the Iranian-backed Houthis took over the capital Sana’a, and it might well have ended six months later, when the president fled a Houthi advance on Aden. Instead, Saudi Arabia led a coalition of ten Arab countries—supported by the United States—in an air and ground campaign against the Houthis. Since then, the war has ground on, with a new dimension of fighting opening recently between southern secessionist militias—many of which receive support from the United Arab Emirates—and government forces backed by the Saudi coalition. Since taking office, the Trump administration has increased American air strikes in Yemen six fold.

As with most civil wars, the war in Yemen is marked by the influence of outside actors. It began in September 2014, when the Iranian-backed Houthis took over the capital Sana’a, and it might well have ended six months later, when the president fled a Houthi advance on Aden. Instead, Saudi Arabia led a coalition of ten Arab countries—supported by the United States—in an air and ground campaign against the Houthis. Since then, the war has ground on, with a new dimension of fighting opening recently between southern secessionist militias—many of which receive support from the United Arab Emirates—and government forces backed by the Saudi coalition. Since taking office, the Trump administration has increased American air strikes in Yemen six fold.

The phenomenon of outside powers supporting different sides in civil wars is not unusual, of course. Civil wars are often beholden to the whims of external forces. It is surprising, however, that the scholarly literature on civil war termination has not addressed systematic changes over time in the ways in which external powers seek to end civil wars.

In a recent article published in International Security, we find that civil war termination varies by time period. We identify three important shifts in recent history. During the Cold War, most civil wars ended with complete defeat for the losing side. After the Cold war, most ended in negotiated settlement. Since the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001, civil wars still tend to end in negotiation, but not when a terrorist group is involved. Why would the nature of civil war termination vary by time period?

Civil wars tend to end the way that external forces think they ought to end. In other words, norms—ideas of appropriate behavior—play a direct role in civil war outcomes. During the bi-polar era of the Cold War, both sides believed that wars should end in military victory. Neither side was willing to negotiate compromise solutions. As a result, most civil wars ended in victory. With the end of the Cold War, and the rise of democratic unipolarity, the great powers (and a wide array of multilateral organizations) contended that civil wars should end in negotiation, as a path to democratization. And indeed, most civil wars after that point ended in negotiation. Since 9/11, although the norm of negotiation remains strong, a countervailing norm of non-negotiation with terrorists means that the appropriateness of military victory is once again ascendant. Instead of seeking democracy, the United States and others are promoting a new norm of “stabilization.”

Norms are notoriously difficult to pin down empirically. A key measure is the extent to which great powers use words associated with those norms, followed by action. The United Nations Security Council is the highest international authority that makes decisions about the legitimacy of the use of force. Most mediation efforts, and eventual negotiated settlements, enjoy the blessing of the Council’s permanent five members—China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States. It is therefore important to analyze normative trends in the Council, which reflect the preferences of its great-power permanent members.

The Security Council issues annual reports that survey the issues that the Council, and other UN bodies, deem worthy of attention. In analyzing the content of these reports, some striking normative trends become apparent.

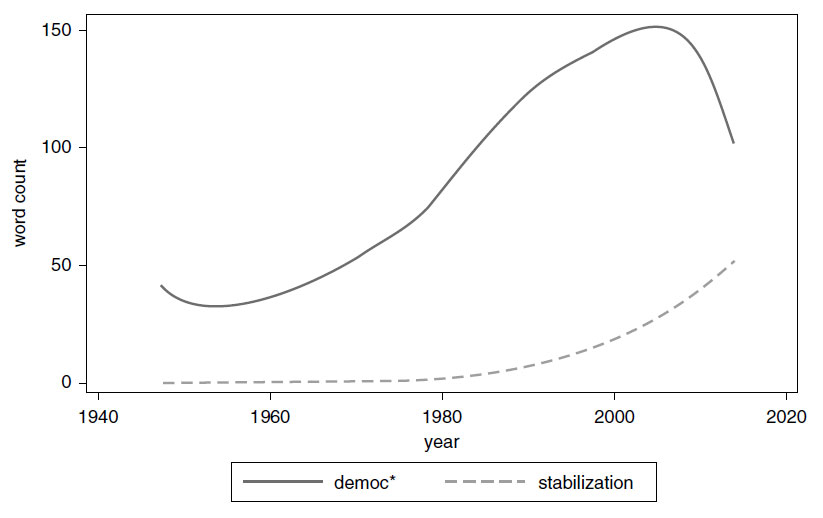

In the figure below, we see a dramatic increase in the word “stabilization,” while words associated with the norm of democracy promotion (democratize, democratization, etc.), decrease after 9/11.

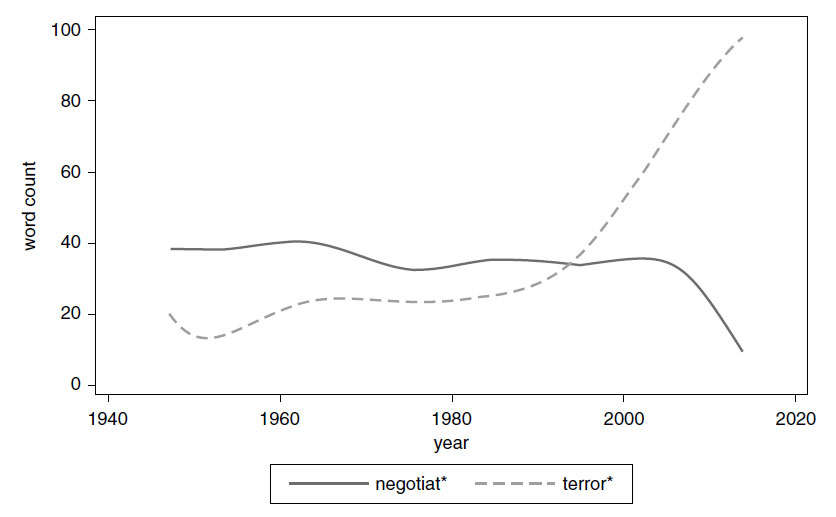

The next figure depicts another set of normative trends important for civil war termination: instances of great power use of words associated with the norm of negotiation (negotiations, negotiating, negotiator) decrease in line with an increase in the use of words associated with terrorism (terror, terrorist). These trends reflect a decrease in the norm of negotiated settlements in civil wars: external powers ought not negotiate with terrorists.

Civil wars are an important international problem. Such conflicts give rise to critical global security threats such as mass displacement, organized crime, and terrorism; these wars are lasting longer, drawing more external involvement, and generating more civilian casualties than ever before. The trends are evident in Yemen, where the violence grinds on with no end in sight. Mediation attempts have failed in large part due to insufficient buy-in from external actors. Meanwhile, terrorist organizations like AQAP and ISIS flourish in the chaos.

It is imperative for scholars and policymakers to decipher and explain large-scale trends in how civil wars end. There is no easy solution to these complex and destructive wars, but our findings show that external actors play a crucial role in determining how (and whether) civil wars conclude. Civil wars end the way that external powers think they should end. For Yemen, until external powers agree on how the civil war ought to end, it will not cease.

No comments:

Post a Comment