FINBARR O’REILLY

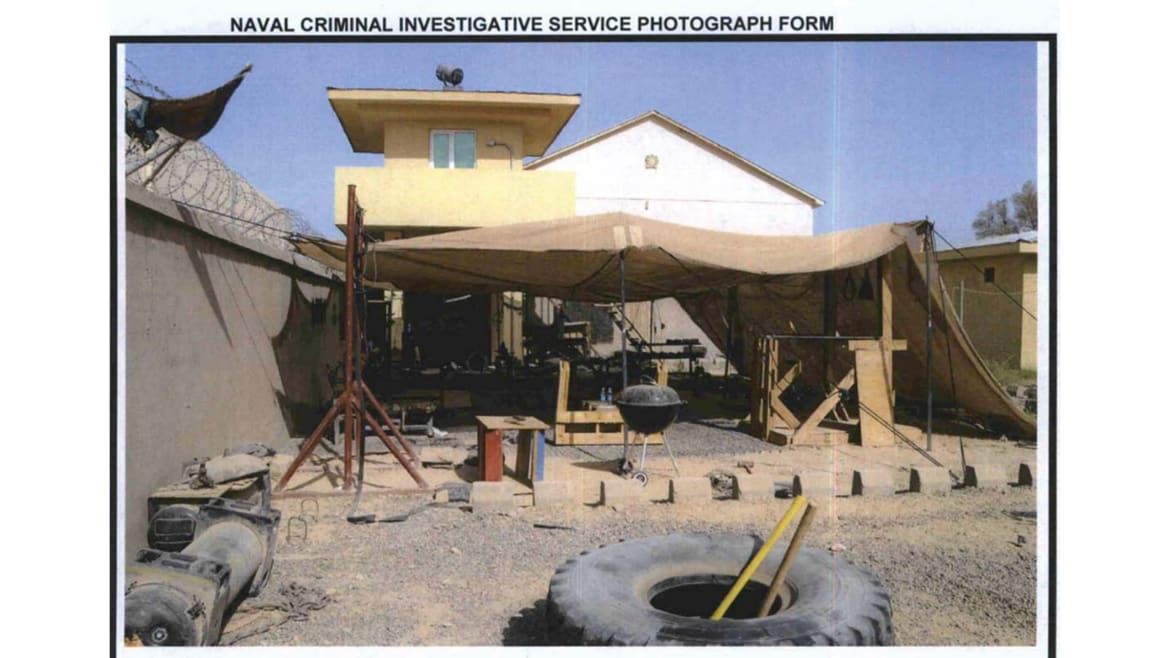

After sunset most evenings in Afghanistan, Cody Rhode and his friend, Scott Dickinson, would lift weights in an outdoor gym.

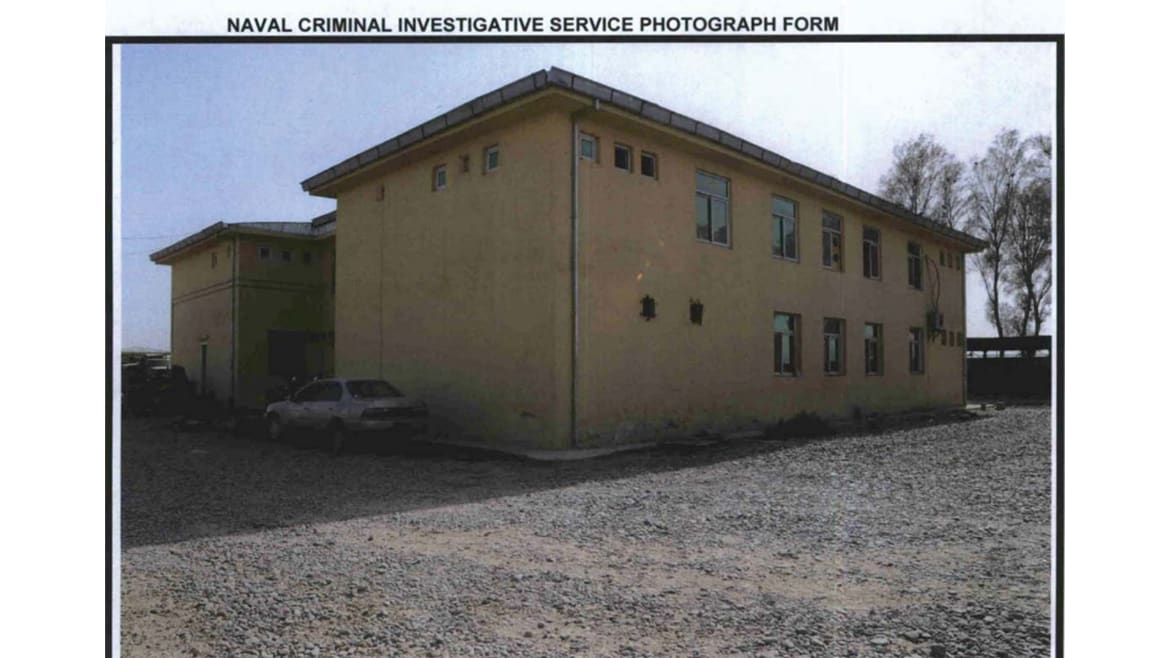

The U.S. Marine staff sergeants were just days from completing their 2012 deployment on the Afghan National Police compound of Forward Operating Base (FOB) Delhi, a joint U.S. and Afghan security forces base. They were part of a small police advisor team responsible for training Afghan police at the base, in an abandoned agricultural college building in the Helmand River valley district of Garmsir.

Around 8 p.m. on Aug. 10, 2012, which the Marines present described as an unusually dark, moonless night, the two friends entered the gym, where Cpl. Richard “Richie” Rivera and Lance Cpl. Gregory “Buck” Buckley Jr. were already working out. Soon after, they were joined by Sgt. Daniel Burlap and U.S. Navy Corpsman David “Doc” Oliver.

The workout buddies were doing chest presses at the flat bench, next to the gym entrance. Rhode was wearing headphones and listening to Steely Dan on his iPod. He moved to a different machine under the guard tower at the back of the gym. Dickinson stayed at the bench.

Their last minute of peace was 8:19 p.m.

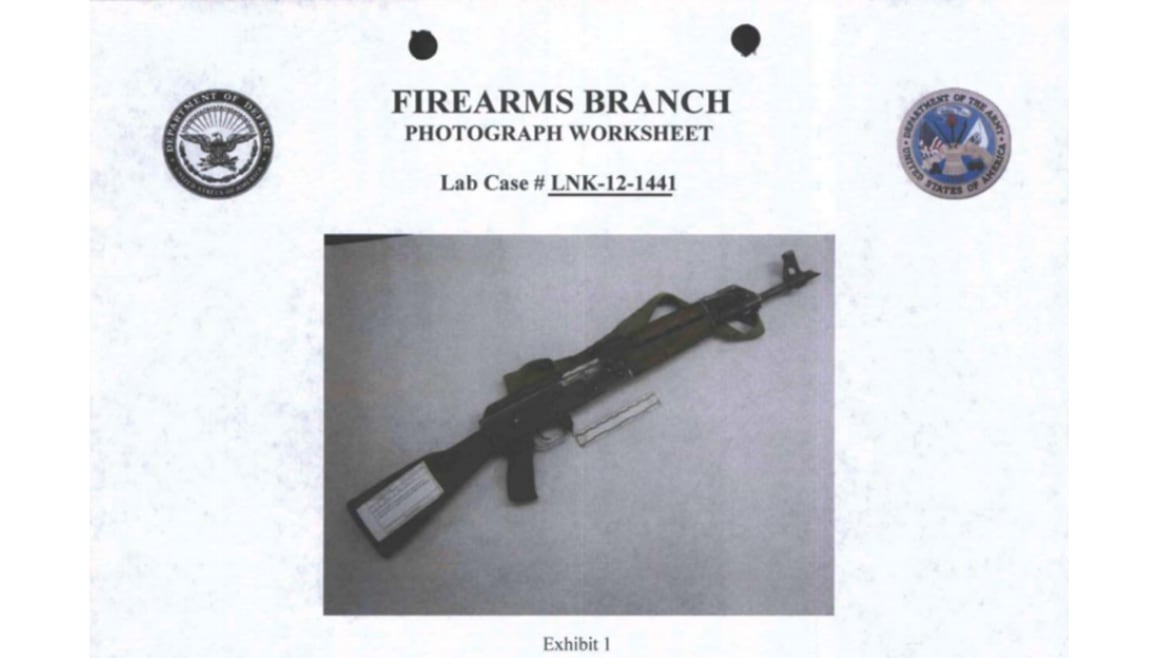

At 8:20, a young man in traditional Afghan dress approached the gym’s entrance, carrying an AK-47 set on full automatic fire.

The Longest War

More than 16 years into America’s longest war, a resurgent Taliban has frustrated U.S. and Afghan government efforts to build a stable state. The Trump administration in August announced a surge of more than 4,000 additional American troops into Afghanistan, where about 14,000 American forces are now operating.

More than 16 years into America’s longest war, a resurgent Taliban has frustrated U.S. and Afghan government efforts to build a stable state. The Trump administration in August announced a surge of more than 4,000 additional American troops into Afghanistan, where about 14,000 American forces are now operating.

Training Afghan security forces and police remains one of the most dangerous and frustrating tasks for American troops. U.S. military officials say Afghan security forces remain dependent on American assistance and are not ready to defend their country without foreign help. And yet the war ticks on, now with a casualty count of 2,216 dead and 20,050 injured on the U.S. side (PDF).

2012 was the bloodiest year for green-on-blue attacks, or Americans killed by the Afghan security forces they were training. It was also a turning point: The high body count caused the U.S. to pull back from direct interactions with Afghan forces—but from a safer distance, American forces have struggled to train Afghans effectively enough to defeat the Taliban and run the country.

Aside from killing the Taliban and Islamic State militants that have begun to operate within the region, the U.S. has a mandate to advise, train, and assist Afghan security forces, including local municipal police departments.

In the Spring of 2018, the U.S. Army will send its newly formed Security Force Assistance Brigade (SFAB) to Afghanistan to take over the training mission. But the SFAB is ill-equipped to train the Afghan National Police (ANP), as most of the soldiers have little law enforcement experience—much like the Marines training Afghans on FOB Delhi in 2012.

Many of the Marines who spoke to The Daily Beast have never spoken to the press about what took place at FOB Delhi. Now that more than five years have passed and the final investigations into the incident have concluded, the Marines who were there say they want America to see the war with clear eyes.

Rhode and Dickinson were scheduled to leave FOB Delhi in a day and a half to start their team’s rotation back to Hawaii. There were no plans to insert a new police advisor team once they were gone.

“[Insider threats] were my biggest fear going into this thing,” Rhode recalled. “We all knew that the threat wasn’t outside the wire, it was inside the wire.”

August 2012 was a particularly dangerous time for U.S. and NATO coalition forces inside Afghanistan, with several green-on-blue incidents. Earlier on Aug. 10, three Marine Raiders, the Corps’ special operations forces, were killed in Sangin when an Afghan police officer opened fire on the Marines after sharing an early-morning meal. By the end of Aug. 10, six Marines would be dead from a pair of attacks, making it the highest-casualty day of that year for green-on-blue attacks on American forces.

August 2012 was a particularly dangerous time for U.S. and NATO coalition forces inside Afghanistan, with several green-on-blue incidents. Earlier on Aug. 10, three Marine Raiders, the Corps’ special operations forces, were killed in Sangin when an Afghan police officer opened fire on the Marines after sharing an early-morning meal. By the end of Aug. 10, six Marines would be dead from a pair of attacks, making it the highest-casualty day of that year for green-on-blue attacks on American forces.

Long War Journal, a website that tracks combat reports from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, reported a record 44 “insider-threat” attacks in Afghanistan in 2012, compared with only 16 for 2011, a 175 percent increase. Green-on-blue accounted for 15 percent of the deaths of coalition forces that year in Afghanistan. A total of 99 insider attacks have taken place in Afghanistan from 2008 to the present day.

Training and working with local Afghan police and military remains problematic for American forces today, but 2012 was the peak year for American deaths at the hands of their Afghan allies. As Trump tweeted in 2012, “Why are we continuing to train these Afghanis [sic] who then shoot our soldiers in the back? Afghanistan is a complete waste. Time to come home!”

After several years’ decline starting in 2013 in the number of American troops killed by insider attacks, that total is back on the rise, the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR) wrote in an Oct. 2017 report to Congress (PDF).

After several years’ decline starting in 2013 in the number of American troops killed by insider attacks, that total is back on the rise, the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR) wrote in an Oct. 2017 report to Congress (PDF).

James Cunningham, senior analyst for SIGAR, said the U.S. military had long struggled to train Afghan security forces safely and effectively, and that despite the changes, problems have persisted.

“The U.S. government lacks a deployable police training force to high threat environments,” Cunningham wrote. “That is still a gap.”

The training gap made for frustrating deployments for U.S. forces. While half the team at FOB Delhi had a background in law enforcement, other teams throughout the country were not so lucky, with some police advisory teams having no actual police officers, so they struggled to teach the basics of law enforcement to Afghan police, many of whom were poorly educated.

“One U.S. officer watched TV shows like COPS and NCIS to learn what he should teach,” SIGAR found. “The U.S. government was ill-prepared to conduct security-sector assistance programs of the size and scope required in Afghanistan, whose population is about 70% illiterate and largely unskilled in technology.”

At FOB Delhi in August 2012, the police advisory team had turn over internal security to Kilo Company 3rd Battalion, 8th Marine Regiment (3/8), an infantry battalion out of Marine base Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, just a few days before the shooting. The police advisory team was about to rotate back to the U.S.

On Aug. 10, 2012, the Marines were advised not to leave the secure area of the police compound because of threats associated with the Ramadan holiday. Rhode noticed Afghans praying more often than usual, but nothing else out of the ordinary.

Rhode said that up until that evening, the Marines were always nice and friendly to the Afghan police recruits on base, helping them solve problems and procure supplies. And for a few months in 2012, a small group of Afghan police recruits between 15 and 22 years old would closely observe the Marines’ gym workouts on FOB Delhi, he said.

“It was really awkward,” Rhode told the Naval Criminal Investigative Service (NCIS) in 2012. “They would squat down right in front of you and watch you work out. It was like they knew it was uncomfortable for us. I remember one of them took a drink from my water bottle while I was working out. I looked at him and all he said was, ‘What?’ It was as if he was trying to push me to get mad so he would have a reason to retaliate.”

In the weeks before Aug. 10, 2012, a young Afghan man who was the assistant to a local Afghan police chief would serve chai tea and help the Marines differentiate between Dari and Pashto police recruits, because the two Afghan ethnic groups did not get along.

Lance Cpl. Buckley often stood post at the entry control point that separated the Afghan Police side of FOB Delhi from the Afghan Army side. An unnamed Marine told NCIS that Buckley and one Afghan “chai boy” would regularly talk and trade juice boxes for Gatorade.

That chai boy was Ainuddin Khudairaham, later identified as the shooter.

The NCIS investigation determined that on the day in question, Ainuddin found a loaded AK-47 in the barracks room of an Afghan police officer who had left it unattended, according to transcripts of interviews with Afghan police officers present at the attack. Just after dark, Ainuddin picked up the rifle and walked across a courtyard toward the outdoor gym.

COURTESY OF LA PORTA

COURTESY OF LA PORTA

Rhode had earphones on when the shooting began, so it took him a few seconds to process what was happening. None of the Marines in the gym were armed; one said he had placed a pistol on a table but couldn’t get to it.

“I realized what was going on by the fifth shot,” Rhode said. “I could see the sparks flying. I had headphones in, which now that I think about it was stupid, not to mention not having a gun.

“I was behind one of the pylons and I could see the bullets flying by me because [the shooter] had walked in from the front, shot Buckley in the back and then he turned and shot at Dickinson, and he was spraying,” Rhode said. “He wasn’t aiming, he just had it on auto and he was spraying.”

The gunshots were coming from near the entrance to the gym, fanning from the shooter’s left to right. Rhode saw another Marine desperately trying to squeeze through a narrow gap between a fence and a back wall, so he sprinted toward him like a linebacker and rammed the Marine and himself through. He saw Oliver, the corpsman, jump over the fence behind him.

Rhode was shot twice in the left shoulder, twice in the left thigh, and once in his right elbow, but he kept moving. He sensed that the shots were now coming from above, but he couldn’t see the shooter.

An armed Marine took cover behind some parked police trucks near the Afghan police headquarters building, according to NCIS documents. He saw the sparks of bullets hitting weight machines, and then he saw two of the injured—Rhode and Rivera—run past him, into the police building.

“Staff Sergeant Rhode yelled ‘live shooter, get the fuck out here,’ and then he threw on his gear and body armor, grabbed his weapon and started running out the door,” said Capt. Brian Harrington, who was the commander of the police advisor team (PAT). “Oliver and another corpsman had to tackle him and hold him down, because he was trying to run back outside after getting shot five times.”

Oliver tourniqueted Rhode’s three injured limbs and treated his wounds. Rhode survived, but with severe damage to his right arm. The remaining Marines split into two groups: one to evacuate and care for the wounded, the other to capture or kill the shooter.

Ainuddin entered the guard tower and asked for help from the Afghan police inside, but they wrestled the AK-47 away from him. Ainuddin then jumped out of the window of the tower, onto a narrow wrap-around balcony where a Marine sergeant engaged Ainuddin in hand-to-hand combat and captured him.

The Fallen

When the shooting began, Dickinson, 29, was shot immediately, bullets tearing through his groin and torso. He died soon after.

“I had been with Dickinson since day one,” Rhode said. “He was real funny. He was a good [staff sergeant], he knew his job well. He knew how to do logistics right and he knew how to take care of his Marines. He was always volunteering to go out on combat patrols.

“He was a good guy, a real good guy. He was my workout buddy.”

Buckley, 21, was shot through his neck, his clavicle, and his upper chest. Gravely wounded, he managed to exit the gym area, but his body would be recovered between the guard tower and the fence with the small gap.

Rivera, 20, was shot through the left side of his neck, and despite massive blood loss, he escaped the gym, but collapsed some 30 feet from the entrance of the police headquarters building from the massive blood loss, where he went into cardiac arrest. Harrington said he stumbled over Rivera in the dark, and when he touched him, his hands were wet with blood.

Doc Oliver performed CPR and tried to stop the bleeding, but Rivera died in his arms.

Four days after his death, a deputy medical examiner for mortuary affairs at Dover Air Force Base performed an autopsy on Rivera. The examiner listed only one personal effect: a Casio G-shock watch, still ticking.

Ainuddin was interrogated for nine days by a team of Marines specializing in counterintelligence. He toggled between denying his role in the shooting and saying he had no memory of it; he said he had no ill-will toward the Marines stationed at FOB Delhi and no intention to wage jihad; and he indicated that someone else, possibly the Afghan officers in the guard tower, framed him for the shooting.

A panel of Afghan judges convicted Ainuddin of multiple counts of murder and sentenced him to seven and a half years in prison, the maximum sentence allowed for a juvenile. Today Ainuddin remains in prison in the Afghan National Detention Facility in Parwan province, near Bagram Air Field.

The Warning?

In the shooting’s aftermath, the Marines who were stationed at FOB Delhi, along with some of their families and lawyers, argued about whether the attack might have been prevented.

“If the MEF guidance and Col. Healey’s guidance regarding guardian angels had been adhered to, those Marines would probably still be alive.”

— Intelligence Analyst

In early 2012, five months before the FOB Delhi shooting, Marine Gen. John Allen, the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) commander in Afghanistan, instituted the “Guardian Angel” strategy: American service members and coalition forces interacting or training their Afghan counterparts would be watched at all times by a sentry with a loaded weapon, in case an insider attack occurred.

There was no guardian angel at FOB Delhi’s outdoor gym on Aug. 10 at the time of the shooting, but they were present earlier in the day. An intelligence analyst for 3/8 at the time, who asked that only his first name, Kevin, be used, said that strategy was the one warning that might have made a difference.

“If the MEF guidance and Col. Healey’s guidance regarding guardian angels had been adhered to,” Kevin said, “those Marines would probably still be alive.”

Two days after the shooting, Pentagon officials announced ISAF would increase intelligence and counterintelligence operations to prevent green-on-blue attacks. American and coalition troops were ordered to carry their loaded weapons with them while on base, and they were banned from wearing headphones because it interfered with “situational awareness.”

Buckley Sr. and Buckley’s aunt Mary Grosseto believe that if the commander of the police advisory team had heeded an alleged warning to separate the Marines from Afghans on base, Buckley Jr. might still be alive.

In a call home three months before the shooting, Buckley Jr. supposedly predicted his own death on FOB Delhi at the hands of an Afghan ally, his father recounted in a 2013 speech: “Dad, I’m scared. I’m not scared about being out there and fighting, I’m scared about being murdered at night while I’m sleeping. These people sleep underneath me.”

The Marines slept on the building’s second floor, the Afghan officers on the first.

Other Marines on FOB Delhi at the time had a different impression of Buckley’s state of mind, describing him as gregarious and happy even in the tough conditions, and saying he had friendly relationships with the Afghans on base.

The attorney for the Buckley family, Michael Bowe, told The Daily Beast that Marines present at FOB Delhi at the time complained about security at the Afghan police compound, and that commanders ignored legitimate warnings.

“We do now know the 3/8 Marines at FOB Delhi were concerned about… the security of the PAT [Police Advisory Team] co-located with the Afghan police, and that they told the PAT commander, to no avail,” Bowe said.

A source close to the Buckley family who asked not to be named said that before the shooting, Capt. Devin Blowes, the commanding officer for Kilo Company 3/8, a Marine infantry unit stationed on the American side of FOB Delhi, told the commander of the police advisory team that the shared part of the Afghan police compound was not secure.

The Daily Beast attempted repeatedly to contact Blowes, but no reply was returned.

First Sgt. John Saul, who was the senior enlisted advisor in Kilo Company that had previously served with Blowes in Iraq and elsewhere, said he was present when Blowes recommended they relocate to the American side of the compound because of the elevated threat level, especially during Ramadan. Saul said Blowes warned the police advisory team on several occasions that they were becoming complacent in terms of security on the side of the compound shared with Afghans.

Harrington, the police advisory team’s commanding officer, disputed Saul’s account of the meeting, who Harrington claims was not at the meeting. Harrington said he, Blowes, and Lt. Col. Edward Healey, the commanding officer of 3/8, discussed the Afghan police team’s need to stand on its own and decided that the next group of Marines on their way into the area would sleep on the U.S. side of the compound.

“The conversation happened, but the discussion was not how Saul remembers it and Capt. Devin Blowes, would agree with me. We were never told to, ‘get off that compound,’” Harrington said. “Saul was never even in the room when we had the conversation.

“The conversation with Lt. Col. Healey, who was the battalion commander, was about at what point do we leave, Healey asked us, ‘Hey what do you think about moving off the compound?’ But not from a force-protection standpoint, but like, they [Afghan National Police] need to operate on their own, you’re kind of a crutch for them.

“I was never told by Blowes or Healey that we needed to move out because of force protection concerns, or complacency,” Harrington added.

Healey, who was present during the conversation, confirmed Harrington’s version of the meeting.

“I concur with Capt. Harrington’s recollection of events,” Healey said. He told The Daily Beast that leading up to the shooting, there was no prior knowledge “at any level, from the private first class to the battlespace commander and higher headquarters,” that the Marines of the police advisory team were at risk.

“There was never any imminent intelligence or credible evidence of a threat to those Marines,” Healey said.

After Healey seconded Harrington’s version of events, the Buckley’s attorney, Bowe, told The Daily Beast, “I don’t think we are talking to you further.”

The Daily Beast interviewed six enlisted Marines and officers present at FOB Delhi before and during the shooting, and all said that even if heeded, no warning would have prevented the attack. Rhode, the survivor, said he doesn’t believe the police advisory team received or disregarded a specific warning.

“I think that may be a stretch [that the police advisors were too complacent],” Rhode said. “Yes, we had grown close to the [Afghan National and Local Police], many of the Marines had. They knew them by first name and had become friends, but I always think in the back of everyone’s mind was the thought that at any time, these guys could turn.”

The Survivor

On the shore of a lake in eastern Michigan, Pastor Cody Rhode reels in line with his 2-year-old son.

In the photo he later posts, the golden hour has come to Waters Edge Church. The sun eases behind the trees and the sky is reflected on still water.

Five years after the green-on-blue shooting at FOB Delhi that killed three of his Marine brothers and shattered his elbow, Rhode is not bitter or vengeful. He is contemplative, and he is mostly at peace.

He sympathizes with the American troops still fighting in Afghanistan, struggling to train Afghan forces from a safe distance, and he thinks often of Buckley, Riviera, and Dickinson. “What would they want me to be doing?” he asks.

Rhode has chosen to be a man of family and cloth. The associate pastor has built a modest life in Caro, northeast of Flint, Michigan, with his wife and four children—two girls, two boys. Their days are filled with baseball, ballet, and Sunday school.

“It was a weird day,” he said of the shooting, which he does not view as a defining moment of his military service or life. “We have to remember it’s just a moment—a terrible moment, but a moment. You have to see beyond that.”

Beyond it, to a blue-glass lake at dusk, where Rhode kneels beside his son and teaches him how to fish.

No comments:

Post a Comment