2017will certainly be remembered as a year of political anxiety. Between Trump’s first year in office, Brexit, populist surges in the West, crisis in the Middle East, and rising aggression with North Korea, this year offered plenty of tension and reason to worry about where the world is heading.

Will 2018 offer more of the same, or will the world enjoy more stability?

There will be some cause for hope. The world economy as a whole will improve, fueled by a continued Obama-initiated US recovery (which Trump will gladly take credit for); steady growth in Europe; higher commodity prices; and renewed stability for economies such as Brazil, China, and Russia. Optimism for internationalism and cooperation will begin to overtake the nationalist insularity and division that was en vogue for the last couple of years. Leaders such as France’s Emmanuel Macron, Germany’s Angela Merkel, and Canada’s Justin Trudeau will look to steer the global community towards concrete actions on major issues, including climate change, migration, and humanitarian crises (don’t hold your breath on major breakthroughs though). 2018 will also see the demise of Islamic State, which just might lessen the turmoil wrought on by terrorist groups around the world.

But there will also be lots of cause for concern. President Trump will become the world’s biggest impediment to global diplomacy and order. His insistence on turning the US inwards will hamper multilateral efforts on poverty reduction, the refugee crisis, counter-terrorism, and climate change, among others. His lack of strategy and blatant lack of fitness for the presidency will make tensions with Iran and, in particular, North Korea (who might have a fully capable nuclear warhead by year’s end) all the more worrisome. Short-sighted and hateful policies such as expelling migrants from poor countries, moving the US embassy to Jerusalem, and slapping protectionist tariffs, will make the US one of the most hated countries again. 2018 might indeed be the year the US, for the first time since the turn of the 20th century, gives up its leadership role in the global community.

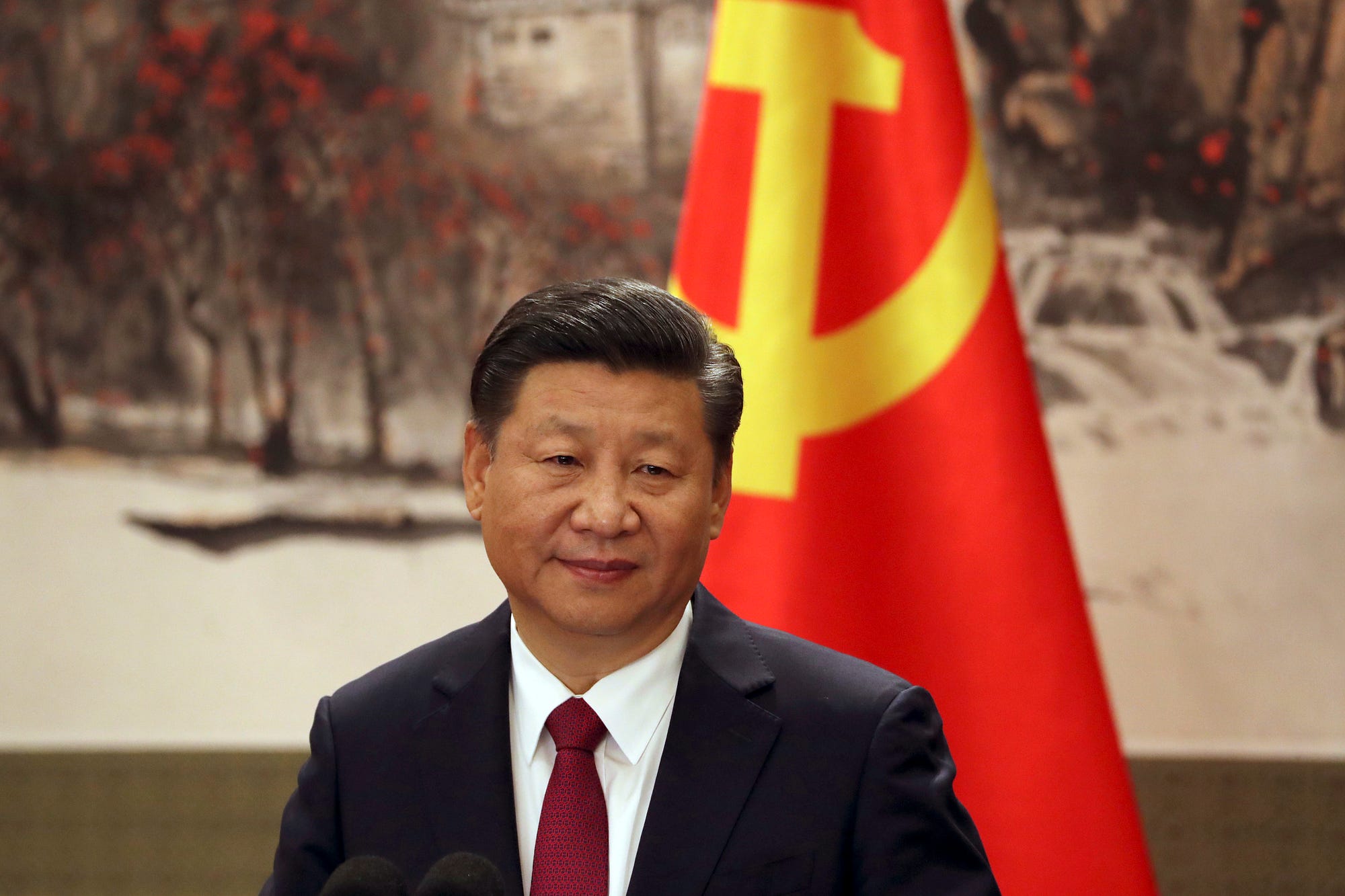

Autocrats and dictators, no longer fearing pressure from the US, will be emboldened to further suppress the voices and rights of their own people. Despots such as Vladimir Putin, China’s Xi Jinping, and Iran’s Ali Khomenei will look to further their regional sphere of influence. Positive resolutions to current conflicts — be they in Yemen, Syria, South Sudan, or Myanmar — will be increasingly difficult and unlikely.

What else might we see next year? Here are some of our other predictions:

No, at least not in 2018. However, Chinese President Xi Jinping, fresh from his October consolidation of power, will look to further establish himself as the center of government authority. He will do so by sidelining any potential source of dissent or opposition. Expect further crackdowns on human rights in China over the coming year, particularly the suppression of free speech.

The economy will be Mr. Xi’s most pressing concern, however. China registered a robust 6.9% growth rate last year, surpassing many expectations. However, economists foresee a slowdown this year, as the country balances away from industry towards a service-based system. This is not, in and of itself, a bad thing; however, China faces major obstacles to make this shift. China’s growth has increasingly been fueled by debt, which now stands at a whopping 274% of GDP. Many of the country’s banks are also holding billions in bad loans, prompting fears of a bubble.

Mr. Xi will opt for stability over major reform. Expect a continuation of his forays abroad, from efforts on climate change, new regional trade deals, and progress on China’s ambitious One Belt, One Road initiative. In our current unpredictable era, it is almost fitting that an authoritarian ruler may become the world’s elder statesmen.

Though this year looks to be filled with surprises, Russia’s elections in March will not be one of them. President Vladimir Putin will be re-elected to another six years in an election put on more for show than anything else. The main opposition figure, Alexei Navalny, has been banned from running; all other “opponents” are there for appearances only. Another round of protests is surely likely, but will be suppressed (possible violently).

Once Mr. Putin is done with those formalities, he will look forward to a big year ahead. He will be hosting the 2018 World Cup this summer, which will give him the sort of world stage he needs to project himself as his country’s supreme ruler. To make sure he faces no international backlash during his time in the spotlight, Mr. Putin will most likely strike a more diplomatic tone abroad for a while, at least outwardly. Some resolution on Syria is possible, and there may be a reduction in online attacks on Western elections, though the question of Crimea will not be on the table.

Mr. Putin will get some temporary reprieve from Russia’s economic hardship. Though the US is prepared to launch a new round of sanctions, rising oil prices will stabilize the Russian ruble and usher in modest growth. This will make for prime propaganda fodder for state-owned media but will belie the country’s acute lack of any other viable industry other than extracting resources. Mr. Putin’s re-centralization of the economy, via the creation of massive state-owned enterprises, has stifled innovation and private enterprise. Initiatives such as the Skolkovo project, Russia’s attempt to create its own Silicon Valley, look like a drop in the bucket to bridge this gap.

This will not matter much to Mr. Putin, as it will do little to affect his grip on power. Ironically, 2017 marked the centennial of the Russian revolution, the socialist overthrow of tsarist reign. 100 years later, Tsar Vladimir will hold firmly to his throne.

The past few years have seen right-wing populists and nationalists enter the forefront of politics in the West. In 2018, such parties will look to cement themselves within the standard political spectrum. In addition to midterm elections in the US, elections in Italy, Sweden, the Czech Republic, and Hungary will test the West’s acceptance of far-right, populist, nationalist, Eurosceptic, and/or xenophobic platforms. Such messages will also be tested outside of the West as well.

In Italy, the anti-establishment M5S will most likely gain the most votes. Their libertarian platform includes calls for direct democracy with internet voting, which appeals to many young Italians disillusioned with mainstream politics. However, they lack no clear ideas for governing and will find it hard to form a coalition given that they have forsworn not to do so. If M5S commits to this resistance, Italy may indeed see a fringe party in government, along with a familiar face. Silvio Berlusconi, he of the massive corruption scandals andbunga-bunga parties, is gearing for a return to politics. His centre-right Forza Italia may be able to cobble up a coalition, ending up in bed with a far-right outfit such as the neo-fascist Brothers of Italy or, more likely, the anti-immigration Northern League in order to get a majority.

Other outfits such as the nationalist Sweden Democrats will also look to continue the far-right wave. In Hungary, mainstream parties may be tempted to strike a deal with the fascist Jobbik party, which may emerge as the main opposition to autocrat Victor Orban and his Fidesz party.

Elections will not be the only indicator of the far-right’s reach. Parties who are in opposition, from Germany’s Alternative for Germany to Marine Le Penn’s National Front, will look to make a mark on major political issues. Chief among them will be immigration, where they will succeed in pressuring governments to cut down on the number of migrants they allow into the continent.

The one to watch is Austria’s Sebastian Kurz. If the 31-year old conservative is able to cater to the far-right and lead a legitimate government, he will become a bizarro Macron-like figure that nationalists the continent over will rally around. Comparisons to a more prominent former charismatic leader from Austria will abound.

2018 will also see the same anti-establishment mood spread to Latin America. In Mexico, it will be Andrés Manuel López Obrador, a far-left populist, who will likely capitalize on such sentiment. He has endeared himself to voters as an alternative to the ultra unpopular incumbent Enrique Pena Nieto, and also by promising to reduce corruption and stand up to President Trump. Critics see in AMLO (as he is called) a Chavez-lite, one who will stir up nationalist fervor to enact radical socialist policy damaging to the economy and the rule of law. His mulling of pardoning drug kingpins doesn’t do much to disprove this. If elected, his win will be felt on the other side of the Rio Grande on issues including trade, immigration, and national security.

In Brazil, it is a candidate from the other side of the spectrum who will look to be crowned populist-in-chief. Jair Bolsonaro, a man who takes pride in comparisons to Donald Trump, will look to capitalize on the disenchantment felt by many Brazilians after the massive Operation Car Wash scandal tainted the country’s entire political class. Known for his litany of racist, misogynistic, and homophobic remarks, Mr. Bolsonaro’s popularity is growing, and he is now polling second in a pretty open field. This ought to worry Brazilians who do not want their own Senhor Trump. The favorite, former President Luiz Inacio “Lula” da Silva, has just had his conviction on corruption and money laundering charges upheld in court.

Who Will Fall From Power?

2017saw the fall of two of the world’s longest-ruling heads of state. Zimbabwe’s Robert Mugabe, in power in since 1980, was ousted by the country’s military in November. Two months prior, Angola’s Jose Eduardo dos Santos, who began his rule just a year prior, stepped down voluntarily after elections in August (though he will retain his party’s leadership post.) Will we see another major ruler fall from grace this year?

Many readers of this site will no doubt love to see Trump himself see his comeuppance via impeachment, but that looks unlikely to happen this year. Ditto for Iran’s Ali Kamenei, where protests in December have largely fizzled out without major upheaval. Nicolas Maduro of Venezuela will also likely cling to power, to the detriment of his struggling people. Nor will Africa’s other longtime autocrats — Yoweri Museveni of Uganda, Paul Biya of Cameroon, or Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo of Equatorial Guinea — likely emulate Mr. dos Santos or go the way of Mr. Mugabe.

Yours truly will take some safer bets, and predict three major leaders to go this year. The first is Jacob Zuma of South Africa. His rule over the country has become synonymous with corruption and graft; he has been charged with over 800 counts of them. His mishandling of the economy and blatant cronyism has squandered South Africa’s post-apartheid potential. Though he is not due to step down until 2019, Zuma will likely meet his fate much sooner. Last month, the ruling African National Congress voted in Cyril Ramaphosa — one of South Africa’s richest men, Zuma’s rival, and allegedly Nelson Mandela’s preferred successor — as party leader, over Mr. Zuma’s ex-wife. This has empowered Zuma’s opponents to press ahead in finding a way to remove him. There will not be many in South Africa that will be opposed.

The second bet is on a similarly unpopular leader: Joseph Kabila of the Democratic Republic of Congo. Mr. Kabila has already overstayed his welcome; he was supposed to leave office in December 2016 but has yet to vacate the presidency and call fresh elections. An agreement between Mr. Kabila and the opposition gave him until the end of 2017 to step down and call elections. This has not yet happened, and elections have now been postponed until December 23rd of this year. Mr. Kabila may see his way out before that, however. Protests erupted in the DRC’s capital, Kinshasa, and are being violently suppressed by security forces. The president’s compound in the restless North Kivu region was burned down over Christmas. Four days prior, the American government slapped sanctions on Dan Gertler, an Israeli businessman with huge interests in mining (the country’s biggest source of exports) and close ties to Mr. Kabila, which could hamper the latter’s patronage networks. With civil war (the third in 20 years) a real possibility, the international community will look for a resolution and a peaceful transfer of power. That would be for the best for both the DRC and for Mr. Kabila; his country has never seen a ruler go willingly.

What Else?

2018 features two of the world’s biggest sporting events: the Winter Olympics in February and the World Cup in June. With Russia ousted from this year’s Olympics in South Korea, yours truly is comfortable in predicting the US to lead in medal count.

The World Cup promises to be one of the most competitive this time around, making predictions particularly tough. Let’s go with France, one of the deepest teams in the field, for the win.

Bonne chance to all in the year ahead!

No comments:

Post a Comment