By Thierry Tardy

Thierry Tardy contends that the EU may recognize the importance of expanding security cooperation with third party states to help it boost its own security. However, he also believes that the Union’s partner policies which deal with security lack coherence and strategic direction. So how can the EU improve its strategic approach towards partner countries? And what key issues must the EU grapple with in order to achieve this goal? In this article, Tardy responds to these questions and more.

Thierry Tardy contends that the EU may recognize the importance of expanding security cooperation with third party states to help it boost its own security. However, he also believes that the Union’s partner policies which deal with security lack coherence and strategic direction. So how can the EU improve its strategic approach towards partner countries? And what key issues must the EU grapple with in order to achieve this goal? In this article, Tardy responds to these questions and more.

Recent evolutions in the security realm within and at the periphery of Europe have led to a series of responses and adaptations from the European Union, in the context of the 2016 EU Global Strategy (EUGS). At the heart of those responses to tackle current security challenges are the questions of ‘what to do’, with ‘what capabilities’, and ‘with whom’. The latter relates to the interaction between the EU and third parties, be they states or institutions. How can the EU reach out to these third parties so as to best guarantee its own security?

In its May 2017 Conclusions, the Council of the EU reiterated its commitment to develop a ‘more strategic approach of CSDP cooperation with partner countries’ in line with the three EUGS strategic priorities of ‘responding to external conflicts and crises’, ‘building the capacities of partners’ and ‘protecting the Union and its citizens’. More specifically, the Council called for the development of CSDP cooperation with partner countries in areas that are not necessarily part of CSDP operations and missions per se. This bears particular resonance given that the UK is due to become a third state in 2019.

CSDP partnerships have traditionally focused on two sets of issues: the role of third countries in CSDP operations and missions; and partnerships between the EU and international organisations, the UN, NATO, the African Union and the OSCE in particular (this institutional aspect of the debate is not the object of this piece). More recently, the EU has started to reach out to third states on other security matters, such as terrorism and migration, but also hybrid threats, cyber, and resilience issues. The revised European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP) also features security (and CSDP) more prominently than had been the case initially.

Those evolutions are positive in the sense that they attest to a desire on the part of the EU to be more reactive to evolving threats; yet what characterises the EU’s partnership policies in the security domain is their fragmentation and overall weak conceptualisation. The EU partners with some countries on CSDP operations, with others on counter-terrorism, and with a third group on migration, but the overall coherence of these policies, as well as their visibility is yet to be ensured. In other words, these various policy tracks lack a strategic direction.

What partners?

A key question for all partnership policies is that of prioritisation of partners. Which third countries the EU should establish partnerships with, and on the basis of what criteria? Beyond geography, intuitively partners must share the EU’s values, as well as represent an interest for European security, either as security consumers or providers.

Partnerships imply the idea of pooling (resources) and sharing (gains) in a relationship that cannot be too asymmetrical, lest the very nature of partnership be distorted. But one key theme of the EUGS is also that the EU must become more self-interested in its assertion as a security actor. Any prioritisation must therefore take as a starting point the EU’s own political and security interests rather than a general contribution to international peace.

In this general framework, a typology of potential partners includes at least six categories that overlap to a large extent:

countries where CSDP operations and missions are deployed (currently 11 countries for 16 operations);

countries that have signed a Framework Participation Agreement (FPA) with the EU regulating their participation to CSDP operations (18 countries + Switzerland which although it has not signed an FPA, regularly contributes to CSDP operations);

countries with which the EU has political dialogues on counter-terrorism (more than 20 states, including 13 where the EU has posted security officers);

European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP) countries (16);

candidate countries (5) and potential candidates (2);

countries with which the EU has signed Migration Compacts (8).

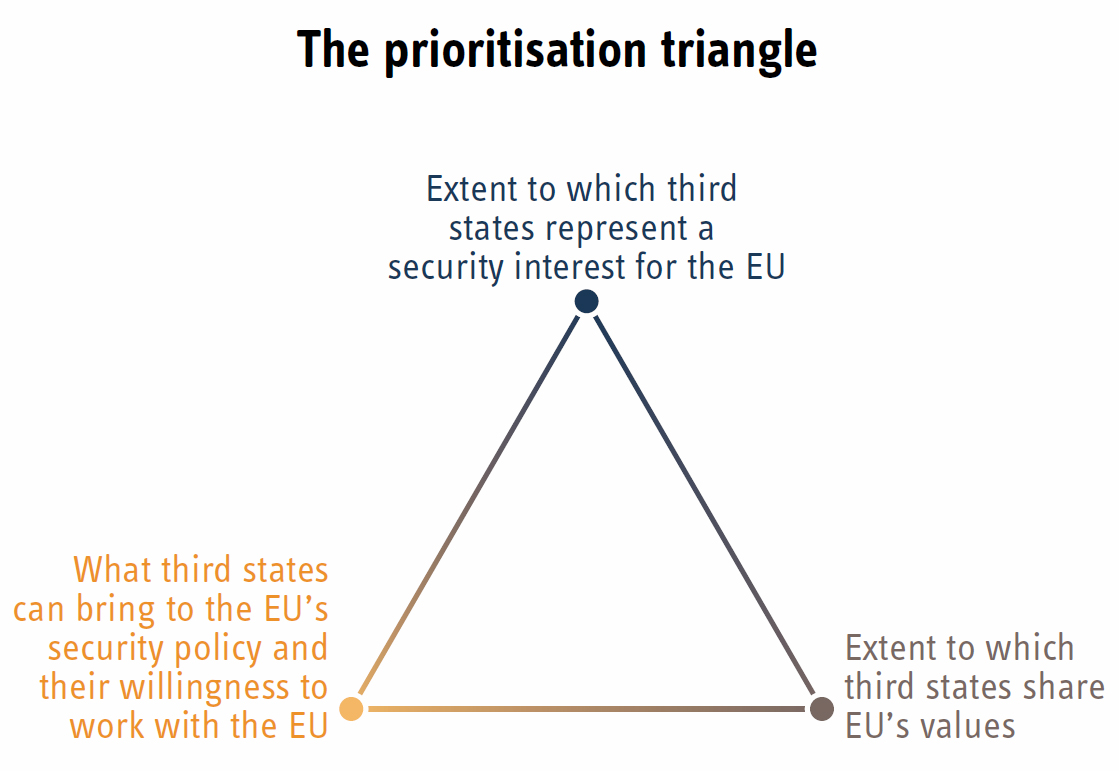

This typology features states that differ significantly in terms of: a) the security interest that they represent for the EU; b) what they can bring to the EU’s security policy, as well as their willingness to work with the EU on a broad security agenda; and c) the extent to which they share the EU’s values and therefore can legitimately cooperate with the EU.

Prioritisation must result from an assessment of these three variables and how each weighs in the overall analysis (see graphic below).

Such a typology also shows the heterogeneity of third states. For obvious reasons, the US or Norway – and soon the UK – are by nature different from, say, Kosovo, Jordan, Mali or Turkey. Not only are third states different from one another, but they may also belong to several of the above six categories, and therefore embrace a security agenda that goes well beyond CSDP operations.

They can, for instance, be simultaneously a contributor to CSDP operations and a host state of such operations (e.g. Bosnia-Herzegovina or Georgia), or an ENP country that has signed a Migration Compact with the EU (like Jordan or Lebanon). This means that dialogue with those states has to be broad-ranging and take account of the various degrees of existing or potential cooperation, both within the EU in Brussels and in situ.

What partnerships?

The Council’s mandate to develop a ‘more strategic approach of CSDP cooperation with partner countries’ raises the issue of the meaning of ‘strategic’ and of the scope of cooperation.

How strategic? ‘

Strategic’ can be interpreted in various ways. When associated with cooperation with third states in the security domain, it is both a means and an end. The means is coherence of EU policy and the end is greater impact, i.e. a better protected Europe or a more capable EU in its response to crises and conflicts.

In terms of coherence, the EU must embed its cooperation with third states on security issues into the broader framework of its external relations, and coordinate internally the various existing policy tracks. This is the idea behind the Integrated Approach: that intra-institutional coordination be operationalised in the field and be impact-oriented.

A more strategic approach to partnership therefore implies that the parallel tracks of dialogues on CSDP operations, counter-terrorism, migration or resilience are not only better coordinated but also upgraded so that they become more ambitious and mutually-reinforcing. While each track is currently being conceived and implemented separately from the others, thinking and acting more strategically requires that they all become one dimension of a broader grand design.

The EU’s cooperation with third states

CSDP Operations-Related Track

Third states as host states of operations/missions

Third states’ participation in CSDP operations/missions (within or outside a Framework Participation Agreement (FPA))

Third states’ participation in exercises/training

Capacity-building in support of Security and Development (CBSD)

Administrative arrangements signed by the European Defence Agency (EDA)

Non-CSDP Operations-Related Track

Counter-terrorism (CT) and countering violent extremism (CVE) (including through the posting of security officers)

Migration

Cyber security

Hybrid threats

Border management

Security sector reform

Non-proliferation

Second, in impact terms, acting more strategically implies that concessions on EU principles cannot be a priori ruled out. The security environment at the European periphery is such that the ‘impact imperative’ is likely to create constant tensions between interests and values as presented in the ‘prioritisation triangle’, with no easy way out. Dealing with countries such as Libya or Egypt are cases in point. Their stability is essential to the EU’s own security and therefore working with them is imperative, yet such cooperation offers no guarantee that EU values and principles are always preserved.

A key challenge of the EU’s partnership policy becoming ‘more strategic’ is to maximise the benefit of a relationship with a third state while minimising what the EU concedes on regarding its own values. Beyond partnerships, the EU will have to navigate through this dilemma if it is to become a fully-fledged security actor.

Beyond CSDP

In this context, the extent to which CSDP must be central to cooperation with third states is open to debate.

By nature, CSDP missions and operations are supposed to contribute to the stability of third states where they operate. More specifically, they fulfill a capacity- building role in different forms, be it through the training of armed forces (EUTMs in Somalia, Mali, and the Central African Republic) or security sector reform (EUCAP Sahel Mali and Niger, EUAM in Ukraine and the newly-established Advisory Mission in Iraq). More recently, CSDP operations have also broadened their areas of intervention by playing a growing role in the field of migration or counter-terrorism.

Cooperation with third states has also taken the form of their participation in CSDP operations and missions, formalised through FPAs. Eighteen third states have to date signed an FPA (Albania, Australia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Canada, Chile, Colombia, the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Georgia, Iceland, Republic of Korea, Moldova, Montenegro, New Zealand, Norway, Serbia, Turkey, Ukraine, and the US), and some of them have become key partners in the EU’s CSDP operations. This helps institutionalise partnerships in the security domain by establishing a group of like-minded countries that presumably share the EU’s overall objectives. Third states also participate in the training courses of the European Security and Defence College (ESDC), and dialogues and staff-to-staff consultations on a wide range of security issues are held on a regular basis with more than ten countries.

This said, addressing common challenges with third states today requires a broader approach than the one defined by CSDP operations to include activities such as counter-terrorism, responses to hybrid threats, tackling migration-related phenomena, cybersecurity, or resilience-building. The European External Action Service (EEAS) is now involved in a significant number of these activities in cooperation with third states. And the 2015 ENP Review Joint Communication includes a security dimension with priority areas such as security sector reform; tackling terrorism and preventing radicalisation; disrupting organised crime; chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear risk mitigation; crisis management and response; and CSDP. The definition of Partnership Priorities and updated Association Agendas (within the revised ENP) also include security elements.

This leads to two tracks of security cooperation, one that is directly linked to CSDP operations, and another one that is not (see table above).

The two tracks can be distinct, especially when third states are not involved in CSDP operations in any manner. This is the case with political dialogues on counter-terrorism that the EU runs with more than 20 third states, most of which do not host a CSDP operation. Similarly, most of the cooperation taking place within the remit of the revised ENP is not related to parallel CSDP operations.

The question is then how the CSDP operation track and the broader security track can be coordinated and developed so that they are mutually reinforcing, and support the ‘Protection of Europe’ strategic priority. In the Sahel, for example, the support that the EU brings to the G5 Sahel and the five countries of the region lies at the intersection between CSDP operations – in Mali and Niger – and other types of activities.

An FPA is a relatively narrow agreement which could be upgraded not only to strengthen cooperation with third states in CSDP operations but also to include other considerations that are of common interest to both parties. The HR/VP recently mentioned the idea to “create a mechanism for closer and more constant coordination with the non-EU countries involved in our missions and operations” (Brussels, 13 December 2017). CSDP would then be used as a platform, or an entry point, for developing other forms of security cooperation. The prospect of transferring military equipment to third states in the framework of the Capacity-building in support of Security and Development (CBSD) initiative makes the case for broad-ranging security compacts even more salient.

Towards ‘Security Compacts’?

Although the need for a more coherent or strategic approach to the EU’s security cooperation with third states is widely acknowledged, its operationalisation presents a number of challenges.

First is the issue of the type of framework that can be resorted to. Being strategic has to do with institutionalisation, yet flexibility and tailor-made frameworks are also essential to ensure effectiveness. A trade-off has therefore to be found between a certain level of systematisation of the EU’s policies on the one hand, and customised partnerships on the other. This raises questions about how dynamic cooperation can be in response to evolving circumstances, and how to match EU objectives with third states’ needs. As stated before, a more strategic approach can only be effective if it provides a certain equilibrium in the gains obtained by each party, something which requires that local needs be part of the equation.

The other dimension of the framework issue is whether security cooperation should be the object of a dedicated instrument or whether it simply has to be mainstreamed in existing cooperation channels. Within the ENP, for example, the security dimension is now embedded into broader frameworks, but one idea is also to consolidate existing but parallel security aspects into dedicated ‘Security Compacts’. Such Compacts could be established with a selection of third states, based on common security needs and shared responsibilities, and include specific objectives and timelines. This would grant a higher level of visibility to the security domain, as well as hopefully greater coherence to the various EU policy tracks.

This ties into the degree of inclusiveness of security cooperation, as well as of centrality of CSDP in developing cooperation further. The security dimension of the debate legitimises the role CSDP has to play. But a plea can also be made for an even larger foreign policy framework, with the idea that it is only at the level of the EU’s Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) that any relationship can really become strategic.

A second set of challenges relates to EU internal coordination and the identification of the unit(s) in charge of partnerships in the broader security domain. Whatever upgrading, consolidating and making more strategic existing mechanisms will imply, it is likely that today’s division of tasks within the EU institutions will have to be revisited. When doing so, due consideration will have to be given to the respective prerogatives of the EEAS (and within it, the geographic versus thematic desks), the Commission (and its Justice and Home Affairs agencies), and EU Delegations in situ. For the time being, cooperation on CSDP operations, counter-terrorism or migration fall within different units in Brussels, while EU Delegations are not much involved, but this may well change as cooperation further develops.

What is clear is that EU institutions are not, for the time being, in a position to play a much more strategic role in the field of security cooperation, as illustrated by the lack of dedicated staff in EU Delegations; nor is it a given that member states are willing to grant more power to the EU in this domain. Yet the context created by the release of the EUGS – and incidentally the future position of the UK as a third state – provide an opportunity to examine thoroughly how the EU can contribute to third states’ security and, maybe most importantly, how in return third states can contribute to the EU’s security. This latter point is in itself a revolution as, so far, CSDP has largely been about projecting security outside of the EU; if confirmed, the transition towards a more self-interested security actor will inevitably impact how the EU sees partners and, in return, how those partners see the EU.

No comments:

Post a Comment