BY DEBASISH ROY CHOWDHURY

Vinayak Bhat has been working hard these past months. The retired Indian colonel’s assiduous analysis of satellite images of Himalaya’s Doklam plateau has shredded the veil of peace laboriously woven by India and China since they pulled themselves back from the brink of war last summer, and is raising embarrassing questions for New Delhi on the deal it cut with Beijing to maintain peace in the Sikkim-Bhutan-Tibet “trijunction” area.

Vinayak Bhat has been working hard these past months. The retired Indian colonel’s assiduous analysis of satellite images of Himalaya’s Doklam plateau has shredded the veil of peace laboriously woven by India and China since they pulled themselves back from the brink of war last summer, and is raising embarrassing questions for New Delhi on the deal it cut with Beijing to maintain peace in the Sikkim-Bhutan-Tibet “trijunction” area.

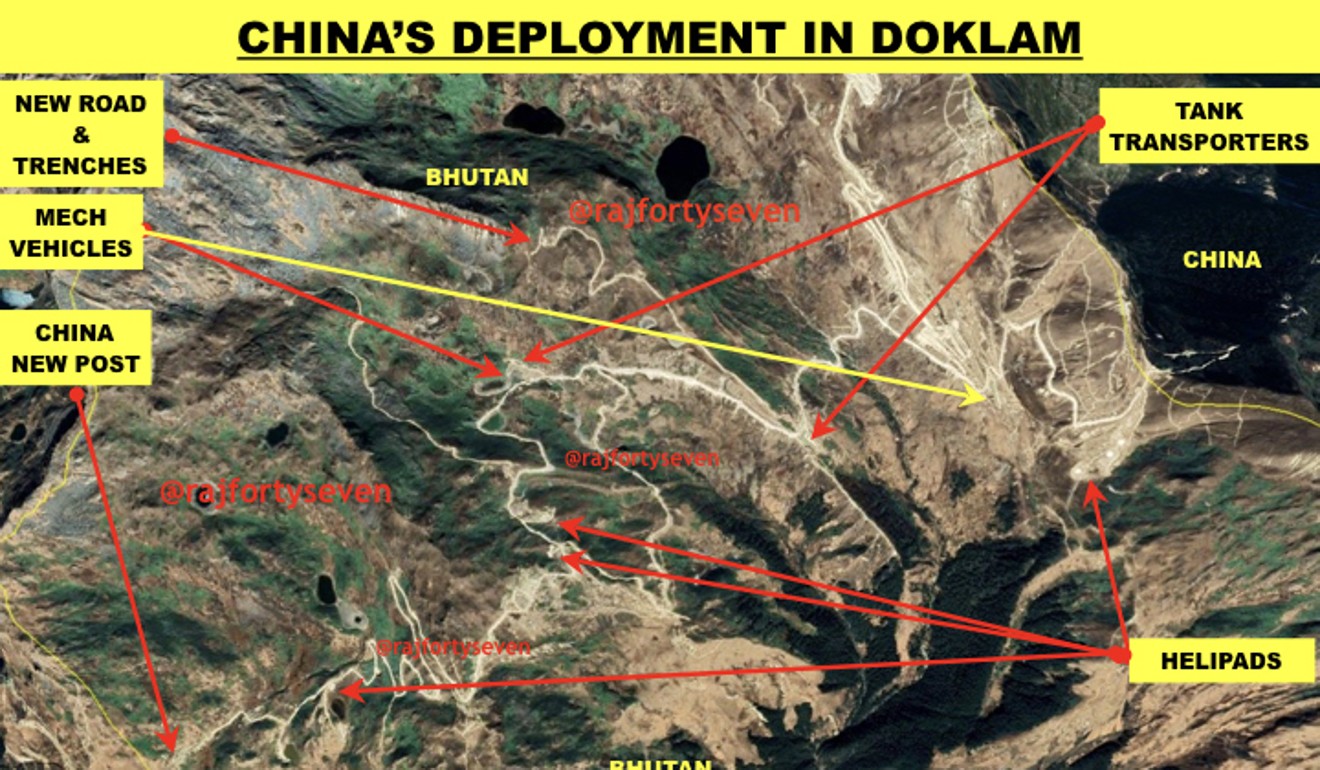

In graphic reports on the online publication ThePrint, Bhat has been detailing the heavy deployment of People’s Liberation Army (PLA) personnel close to last year’s site of confrontation and hectic build-up by the Chinese in North Doklam, including concrete posts, helipads, new trenches, and a concrete observation tower less than 10 metres from the Indian Army’s most forward trench. Fighting posts have been created on almost every hillock on the North Doklam plateau, according to his reports, confirming sporadic media reports of Chinese troops digging in rather than leaving the area.

“All these structures have come up only after June 16, according to satellite images,” the retired colonel, who served the Indian Army for 33 years, told This Week in Asia. “China is trying to change the status quo in North Doklam. India must object because the entire area is Bhutanese land occupied by China.”

The Indian government is doing nothing of the sort and is, instead, insisting all is well. After the opposition Congress party last week cited the satellite images to accuse the government of misleading the country and “snoozing” while the Chinese plan “Doklam 2.0”, the government clarified that the status quo at the site of last year’s face-off still held. It dismissed news reports such as Bhat’s as “inaccurate and mischievous”, but added that it was using “established mechanisms” to resolve misunderstandings over Doklam.

The Indian government is doing nothing of the sort and is, instead, insisting all is well. After the opposition Congress party last week cited the satellite images to accuse the government of misleading the country and “snoozing” while the Chinese plan “Doklam 2.0”, the government clarified that the status quo at the site of last year’s face-off still held. It dismissed news reports such as Bhat’s as “inaccurate and mischievous”, but added that it was using “established mechanisms” to resolve misunderstandings over Doklam.

Addressing the same concerns, Indian Army chief General Bipin Rawat said Chinese soldiers are still present in the area, “although not in numbers that we saw them in initially”, and that the PLA has “carried out some infrastructure development, which is mostly temporary in nature”. But while stressing that “bonhomie” (between India and China) had returned to pre-Doklam levels, Rawat also said it’s time for India to “shift focus” from its western border with Pakistan to its northern border with China, in what Chinese experts like Wang Dehua see as signs of “border aggression from India”.

In an editorial headlined “Time for clarity”, The Hindunewspaper this week noted that conflicting messages from the government pointed to an unravelling of the agreement announced in August, and demanded Delhi “drop the ambiguity” over Doklam and share details of just what’s going on there.

“The Chinese build-up appears to be of a different order of magnitude than anything seen in the past and therefore should be a source of concern,” opposition lawmaker Shashi Tharoor told This Week in Asia. “The government chose to spin the mutual disengagement from the face-off site as a major diplomatic victory. Its silence seems to have more to do with its reluctance to dilute that ‘triumph’ than with any realistic appreciation of the situation,” said Tharoor, who also heads India’s parliamentary standing committee on external affairs. The issue, he said, had come up “repeatedly” in the committee, but declined to elaborate on the “closed-door deliberations”.

“The Chinese build-up appears to be of a different order of magnitude than anything seen in the past and therefore should be a source of concern,” opposition lawmaker Shashi Tharoor told This Week in Asia. “The government chose to spin the mutual disengagement from the face-off site as a major diplomatic victory. Its silence seems to have more to do with its reluctance to dilute that ‘triumph’ than with any realistic appreciation of the situation,” said Tharoor, who also heads India’s parliamentary standing committee on external affairs. The issue, he said, had come up “repeatedly” in the committee, but declined to elaborate on the “closed-door deliberations”.

While the government claimed victory of “quiet diplomacy” to end the stand-off, the politics around Doklam has been anything but quiet.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, left, and Chinese Premier Li Keqiang, centre, hold hands as Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte prepares to chair a meeting at the East Asia Summit. Photo: AP

As an opposition leader before he became prime minister in 2014, Narendra Modi would often criticise the then Congress-led government for its allegedly soft stance towards China. Doklam, coming as it did ahead of crucial regional elections, enhanced his muscular nationalist image as he was seen as having successfully stared China down in a high-stakes battle of nerves.

However, while India’s two-paragraph announcement of truce at the time said both sides were standing down, China never actually admitted it was pulling back its troops. Even as it confirmed that India was withdrawing its border personnel “illegally on the Chinese territory”, Beijing maintained that Chinese troops would continue to patrol the area.

“The brevity of the government’s statements then hid the reality that more than getting the Chinese back to their original position, there was very little we could do,” said Jabin Jacob, a fellow at the Institute of Chinese Studies in Delhi. “But it allowed politicians and the politically minded among the strategic community in India to crow about ‘victory’. The Chinese, on the other hand, can do all they want in the areas of Bhutanese territory that are within their effective control.”

As the controversy in India over the fresh build-up snowballs, Beijing has again asserted that Doklam belongs to China and what it does there is nobody’s business. Chinese foreign ministry spokesman Lu Kang also warned India not to cross the border again like last time – the dispute over Doklam being one between China and Bhutan – and “learn lessons” from it to avoid another confrontation

As the controversy in India over the fresh build-up snowballs, Beijing has again asserted that Doklam belongs to China and what it does there is nobody’s business. Chinese foreign ministry spokesman Lu Kang also warned India not to cross the border again like last time – the dispute over Doklam being one between China and Bhutan – and “learn lessons” from it to avoid another confrontation

If there is another confrontation, it could be a lot more difficult to resolve as “India can’t get away by applying force, as we did last time”, said former army colonel and strategic analyst Ajai Shukla. “A major takeaway for the Chinese from the Doklam incident is the realisation that they need to ditch vehicle-based patrolling and establish a permanent presence on the ground, and that’s what they are doing now.”

Agrees Sourabh Gupta, a senior fellow at the Institute for China-America Studies in Washington, who sees the de-escalation agreement holding up just fine, but a more permanent Chinese presence as the price India has to pay for the tactical win last year.

A satellite image shows Chinese troop deployments in Doklam.

A satellite image shows Chinese troop deployments in Doklam.

“De-escalation was sold in India as a great victory of resolve compelling Beijing to back down. So there is great confusion over how this great victory that Modi won ended up with a larger and more permanent Chinese presence in Doklam, which India does not or will not contest. This is not how the endgame was supposed to be, and this confusion is the source of fears regarding China’s motivations in Doklam,” said Gupta.

For defence experts like Shukla, these fears are mostly misplaced as India holds the higher ground in the southern edge of Doklam compared to Northern Doklam. The spate of infrastructure building may be good optics for the Chinese, they say, but it does not change the status quo on the ground as India is at an advantage there. But with China now beginning to build close-in light infrastructure across parts of the frontier, the real concern for India lies beyond Doklam.

“A much greater worry are other areas where the Indians are at a disadvantage or can’t reinforce as quickly. And it is certain Indian and Chinese forces will come into contact more often along the disputed boundary post-Doklam,” said Jacob. ■

No comments:

Post a Comment