Shyam Saran

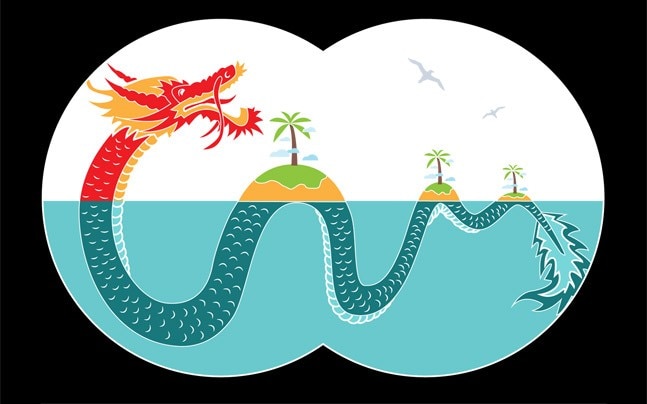

The domestic political crisis in the Maldives may have created fewer waves in India had it not, concurrently, opened the door for Chinese naval power to entrench itself among the islands strung south of the Indian peninsula. President Abdulla Yameen's regime in Male has-since the illegal ouster of Nasheed in a coup in 2012-systematically sought to reduce political, security-related and economic engagement with India even as it has invited Chinese presence, which has rapidly expanded.

The domestic political crisis in the Maldives may have created fewer waves in India had it not, concurrently, opened the door for Chinese naval power to entrench itself among the islands strung south of the Indian peninsula. President Abdulla Yameen's regime in Male has-since the illegal ouster of Nasheed in a coup in 2012-systematically sought to reduce political, security-related and economic engagement with India even as it has invited Chinese presence, which has rapidly expanded.

It began with the cancellation in 2013 of the Male airport project contracted to the Indian firm, GMR, and its award shortly thereafter to a Chinese company. Maldivian property laws were changed in July 2015 to allow foreign ownership of land, provided the investment was at least $ 1 billion and 70 per cent was land reclaimed from the sea. With China's experience in large-scale island building through reclaimed land in the South China Sea, one need not speculate about the likely beneficiary of this new law. In November 2017, on a visit to Beijing, Yameen signed a Free Trade Agreement with China and followed it up with ratification in record time. Chinese and Saudi investors are developing the ambitious iHavan project on the northern island of Ihavandhippolu, not far from India.

It will boast of a modern port, an airport, a cruise hub, a marina and a dockyard. And there are reports that China may build another port on the southern atoll of Laamu with the eventual aim of turning it into a high-end resort for Chinese tourists, who now constitute the largest number of visitors to the country.

China opened its mission in Male only as late as 2011, so this is remarkable progress indeed. China repeatedly forswears any intention of setting up bases in the Maldives, but has signalled its intention to maintain a naval presence in this part of the Indian Ocean by undertaking a highly visible visit, for the first time, of three naval vessels to Male in August 2017. So the message is loud and clear: China is determined to demonstrate its oft-repeated assertion that the Indian Ocean is not India's ocean. And Yameen is happy to be the medium through which this message is being delivered just as Mahinda Rajapaksa in Sri Lanka did earlier by putting his country in hock to China in developing the unviable Hambantota port in the southern part of the country.

It has been argued that Chinese investment in Sri Lanka and the Maldives has been driven by commercial motives and lately by the ambitious Belt and Road Initiative. The fact is that the costs of these large-scale projects are beyond the financing capacity of the recipient countries, which invariably fall into a debt trap. And this leads to vulnerability to Chinese demands driven by geopolitical motives as we have seen in the case of Hambantota. The Maldives is even more likely to go the same way.

What is worth noting is that Chinese naval strategists have made their intentions clear for some time. A couple of years back, a Chinese Navy journal had spelt out the country's Indian Ocean strategy in the form a 16-Chinese character guideline: "Select locations meticulously, make deployments discreetly, give priority to cooperative activities and penetrate gradually."

Chinese activities in the Indian Ocean faithfully follow this playbook laying out starkly what India is up against when it comes to its maritime security. In determining our response to the latest developments in the Maldives and other strategic island countries, one must keep the evolving geopolitical picture in mind. What is happening in the Maldives is important to India-not only because of the rights and wrongs of political actions taken by Yameen but also because of what his continuance in power may mean for the credibility of our maritime strategy. Another way of looking at current developments in the Maldives is to assess whether they provide us with a window of opportunity to stall, if not reverse, the erosion of our influence in a particularly sensitive security theatre.

In 2012, India may have taken the wrong call in not responding to Nasheed's appeal for intervention when he was being forced to resign under duress, paving the way for Yameen's capture of state power. Nasheed was the constitutionally elected head of state and an Indian intervention to prevent the coup against him would have been justified. There are occasions when safeguarding Indian interests requires swift action despite risks involved. A wait and watch approach may sometimes undermine our interests through a relentless attrition process.

Why is it important for China to secure a foothold in these island countries, including not only Sri Lanka and the Maldives but also Seychelles and Mauritius? In the same China Navy journal referred to earlier, it is acknowledged that with India straddling the vital sea lines of communication between the Indian Ocean and the Western Pacific, China would be vulnerable to Indian interdiction or India acting in concert with other major powers such as the US and Japan. Establishing a chain of naval bases or at least naval supply and docking facilities around the Indian peninsula makes sense as a flanking strategy. What could be a credible Indian countervailing strategy? Such a strategy has to contend with the glaring reality that there is a significant economic and military gap between China and India which is unlikely to diminish in the foreseeable future.

There are two policy adjustments suggested in this regard. First, one may need to reallocate resources from less critical theatres to the immediate sub-continental periphery to reverse the erosion in our overall profile. Instead of being thinly spread over a vast geography, this would instead involve a major refocus on the immediate neighbourhood. Two, the Chinese inroads into the Indian Ocean threaten not only Indian interests but also those of other major powers such as the US, Japan and Australia. The American base at Diego Garcia will be affected as will the Japanese commitment to the Indo-Pacific, which the Australians have also bought into. These are also members of the revived though still somewhat hesitant Quadrilateral. There is greater urgency to fashioning a credible role for the "Quad" to prevent unilateral Chinese ingress into the Indian Ocean. India's strategic space is being squeezed by Chinese activities in our immediate neighbourhood. One needs to recognise its ominous implications and take the right calls before the facts on the ground here change in the same manner as they already have in the South China Sea.

In the long run India will need to grow its economic and military capabilities more rapidly in order to reduce the power gap with China. That alone will expand our strategic options. In growing these capabilities, there must be greater priority attached to maritime capabilities. From about 17 per cent of the defence budget currently, the navy should incrementally raise its share to about 30 per cent by 2030. This will be indispensable to maintaining the maritime edge that we enjoy in the Indian Ocean which is being rapidly eroded by Chinese naval expansion.

No comments:

Post a Comment