JAN PIETRZAK has just one demand. He’s not fussy about the design of the centennial arch with which he wants to mark the Polish victory over the Bolshevik armies in 1920. But he does insist that it must be taller than the 237-metre (778-foot) Palace of Culture and Science, given to the Polish nation by Stalin. Mr Pietrzak is a gruff old man with white hair and a fine, bushy moustache, a popular entertainer best known for a patriotic song that became an anthem for Solidarity in the 1980s. Although the Warsaw authorities have balked at his dream of a triumphal arch, he has the backing of the Law and Justice party, which forms the national government. It will be a symbol, he says: “Young people …will know that Poland was victorious—like Trafalgar Square.”

JAN PIETRZAK has just one demand. He’s not fussy about the design of the centennial arch with which he wants to mark the Polish victory over the Bolshevik armies in 1920. But he does insist that it must be taller than the 237-metre (778-foot) Palace of Culture and Science, given to the Polish nation by Stalin. Mr Pietrzak is a gruff old man with white hair and a fine, bushy moustache, a popular entertainer best known for a patriotic song that became an anthem for Solidarity in the 1980s. Although the Warsaw authorities have balked at his dream of a triumphal arch, he has the backing of the Law and Justice party, which forms the national government. It will be a symbol, he says: “Young people …will know that Poland was victorious—like Trafalgar Square.”

The Battle of Warsaw was indeed glorious. The Polish army, facing utter defeat, miraculously stopped the Russians’ advance on the capital. Your correspondent married into a family that still remembers how, during the fighting, grandfather Leon had 17 horses shot from under him. Twenty years later, as Poles were being lined up and murdered in the forest of Katyn, a Russian officer he had spared returned the favour, offering him the choice of the bullet or the gulag. Against the officer’s advice, Leon asked to live.

Commemoration is never just about past valour and suffering. It is about present priorities. Poland is in the grip of a new nationalism. Mr Pietrzak says Law and Justice, which took power in 2015, is the first government to serve Poles well; its predecessors were responsible for a “long tradition of betrayal and treason” with respect to Germany and Russia. Not long ago only a few hundred people turned up to the annual Independence Day parade. This November 60,000 Poles marched alongside two radical-nationalist groups toting banners saying: “Clean blood” and “Europe will be white or deserted”.

Wherever you look, nationalism is rising. Sometimes it takes the form of self-declared nations demanding the right to determine their future: Catalonia in Spain and Kurdistan in Iraq, Scotland in Britain and Biafra in Nigeria. More often it is a lurch to the populist and reactionary right. The Alternative for Germany has won 94 seats in the Bundestag. Marine Le Pen of the National Front won a third of the vote in France’s presidential election. In Hungary, Austria and the Czech Republic nationalists have taken power, just as they did in Poland. In post-referendum Britain they have “taken back control”, or at least pretended to. Turkey is militant, Japan is shedding its pacifism, India is toying with Hindu supremacy, China dreams of glory and Russia is belligerent.

Most remarkable is the nationalist turn in the United States. America was the first nation to declare itself independent of all sovereigns save its people and constitution. It has always seen itself as a place apart. But for most of its history this exceptionalism has been a form of self-regarding universalism; in time, the rest of the world would catch up. Now it has an angry, nativist president who sees America not leading, but being left behind—and vows to make it great again.

People who cross borders and cultures easily, and who prosper as they do so, find this new nationalism disturbing. They see it hindering peaceful countries from trading, mingling and co-operating on the world’s problems. But they tend to think that it will pass, like a fever. It may put off the day when the differences between nations finally melt away; it does not mean that day will never come.

That is to brush aside what is happening far too lightly. Nationalism is an abiding legacy of the Enlightenment. It has embedded itself in global politics more completely and more successfully than any of the Enlightenment’s more celebrated legacies, including Marxism, classical liberalism and even industrial capitalism. It is not an aberration. It is here to stay. Putting aside the concerns of a cosmopolitan elite, this is not necessarily a bad thing. Like religion, nationalism is capable of bringing out the best in people as well as the worst. It can inspire them to bind together freely in pursuit of the common good. But it can also fill them with a terrifying, righteous certainty, breeding strife and injustice.

Sadly, the new nationalism plays to the paranoid, intolerant side of this legacy. It sees every “citizen of the world” as a “citizen of nowhere”, in the mocking phrase of Theresa May, Britain’s prime minister. When the citizens of the world call them bigots, the nationalists retort that the citizens of nowhere are traitors. That turns politics into a test of loyalty. When nations eye each other with contempt, the global order which was stitched together after the second world war under American leadership starts to come asunder. Geopolitics becomes a free-for-all.

To see where this leads you need a handle on what nationalism is and how it works. What connects a skinhead wrapped in the flag of St George to a granny waving at the Queen with a Union Flag on a stick? When Jaroslaw Kaczynski, the head of Law and Justice, whips up one of the mass-meetings at which he peddles conspiracy theories on a chilly Tuesday evening, what alchemy persuades each member of his audience that he is summoning an ancient and personal loyalty? Why would someone avoid talking to a stranger on the bus but lay down her life for him on the battlefield? The answers draw on politics, philosophy and psychology. But they begin with history.

NATIONS have existed for centuries. Nationalism came of age in Valmy, in northern France, on September 20th 1792, round about noon.

That was when, in an engagement as mythologised as the Battle of Warsaw, French volunteers confronted a superior army of Prussian regulars under the Duke of Brunswick. In the crucial moment, General François Kellermann brandished his hat on the end of his sword and roared “Vive la nation!” From battalion after battalion the cry went up, a wave that carried the citizen-soldiers to triumph.

It was the first victory of the Revolutionary War, claimed for the nation not the king. It inspired the National Convention in Paris to be done with the monarchy. A stunned Europe grasped that the divine rule of kings really was coming to an end. The order that replaced it was built on three philosophical claims:

1) Legitimacy is not handed down from God; it surges up from the people. Thinkers like Jean-Jacques Rousseau and John Locke drew on a well-established sense of nationhood, particularly visible in England, to explain how individual citizens have the right to join freely in a nation that will protect and benefit them. Three years before Valmy, Article III of the Declaration of the Rights of Man had said: “The principle of all sovereignty resides essentially in the nation. No body nor individual may exercise any authority which does not proceed directly from the nation.”

2) Government is not just an agreement between individuals, but also a statement of the nation’s general will. As Rousseau argued, individual rights can be qualified: a state wields its power in the name of the collective. Scholars quarrel over whether Rousseau meant to trample on individual rights or protect them from the majority, but governments have used and abused the principle ever since.

3) Each nation is different. By the time Napoleon was invading his neighbours, France’s fraternal claim to be spreading the universal virtues of liberty and equality looked to the rest of Europe very much like brazen conquest. German thinkers turned to the philosopher Johann Gottfried Herder, who insisted that each nation is shaped by its own unique past and that its true essence emerges from history, culture and, ultimately, race. The French could not impose their version of liberty and equality; only Germans could know what those ideas mean for the powers and principalities that would eventually form Germany.

Nationalism slips and slides between these three divergent claims. Flag-waving patriots who get weepy over the Olympic games and the poems of Rudyard Kipling draw on history and culture, but go easy on the general will. Civic nationalists, from places like Brazil, America and Australia that are largely made up of immigrants, exalt universal values and the example their nation sets in pursuing them. They dally with Rousseau’s general will, urging newcomers to assimilate, but tread lightly on race and culture, which are not shared. Ethnic nationalists mine race and history to create a politics that sacrifices individual liberty to the will of the majority.

Some seek to have the good parts of this melange without the bad. Thinkers like George Orwell and Elie Kedourie have argued that patriotism—tolerant, welcoming and reasonable—really has nothing to do with nationalism. It is a comforting thought; it separates decent people from the bigots who cling blindly to their own nation’s superiority. But one person’s patriotism is another’s prejudice. In 1917 the Indian writer Rabindranath Tagore lamented how “the people which loves freedom perpetuates slavery in a large portion of the world with the comfortable feeling of pride in having done its duty.” Genial English patriots were blind to the harm they caused.

The late Benedict Anderson, an Irish political scientist, called modern nations “imagined communities”—imagined because people are drawn together within them who have not met and never will. It is the power of such imagination that allows an essentially modern doctrine like nationalism to feel so deeply rooted in the past. Today’s Polish nationalists hark back to the country’s commonwealth with Lithuania, which at its height, in the 17th century, was one of Europe’s great powers. Zimbabwe takes its name from ruins abandoned hundreds of years before the country’s boundaries were carved out by colonialists. Germany’s 19th-century nationalists romanticised the tribes who fought the Roman legions—which is why Wagner throngs with spear maidens and knuckleheaded heroes.

Today’s nations are, in a sense, products of nationalism, rather than, as nationalists might claim, it is of them. Ten years ago Poland had a couple of magazines that dealt with history; now it has a dozen. The Battle of Warsaw is celebrated, with other landmarks, on T-shirts produced by a popular fashion brand, called Red is Bad. Though having such history to hand is a help, pure fantasy can be drafted into the mythmaking, too. Other Red is Bad designs feature valiant Poles battling Nazi cyborgs and Teutonic knights depicted as villains from “The Lord of the Rings”.

The manipulation of history and culture has a long tradition. The French army beat the Prussians at Valmy because of its professional gunners, rather than its citizen volunteers. Diponegoro, whom Indonesians hail as a national hero for opposing Dutch colonial rule in the 19th century, intended to conquer Java, not to liberate it; Anderson noted that he seems to have had no concept of who the Dutch were nor any desire to expel them. When Italy was unified in 1861, only 2.5% of the population spoke standard Italian. Massimo d’Azeglio, a leading patriot, declared: “We have made Italy; now we must make Italians.” So much for Herder’s unique community bound by language and culture.

This process of national construction can be harnessed for violence and hatred. Simon Winder, an author and publisher, exaggerated when he said on BBC radio some months ago that “nationalism always starts off with folk-dancing and ends up with barbed wire”. But such journeys are all too easy, especially when nationalism is contaminated by theories of racial purity. Then it was able to fuel the Nazi drive to “protect” ethnic Germans in neighbouring countries, and to permit the building of concentration camps and gas chambers. That spectre has haunted nationalism ever since.

But nationalism has liberated oppressed people as often as it has fired up anti-Semites. In the 19th century, beneath the carapace of the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman empires, liberals and radicals built movements of national liberation. After the first world war, when Woodrow Wilson, America’s president, championed the principle of national self-determination, these new nations emerged, blinking, into sunlight, a process typically accompanied by national anthems that sounded like subpar Verdi.

Once Europeans had accepted self-determination, it was just a matter of time before Africans and Asians founded national-liberation movements of their own. James Mayall, a British academic, points out that European powers could sustain empires only so long as they believed that their imperial subjects were barbarians who did not count as people with rights. When the Europeans’ arguments were turned back against them, their great empires collapsed under the weight of their own contradictions.

A new internationalism was born; cosmopolitans looked with pleasure on the United Nations, alike in dignity, diverse in their national dress. They saw a world of nations which, in the words of the 19th-century writer Ernest Renan, “serve the common cause of civilisation; each holds one note in the concert of humanity.” Liberal multiculturalism carries an echo of the same feeling, promising a civic nationalism so strong and legitimate that Herder’s different peoples can jostle along within it, separate yet united.

A lot of movements—most notably Marxism—have aimed to surpass the nation. None has succeeded. Delegates to a pan-Slavic congress in the mid-19th century could not understand each other and had to fall back on German. Pan-Arabism and Negritude failed to unite the Middle East or Africa. Far from creating a post-national caliphate, Islamic State and al-Qaeda have divided Sunni Islam.

The most ambitious attempt to lay nationalism to rest is the European Union. It has succeeded in that war between EU members is unthinkable. But the European nation state has not withered away as some of the pioneers hoped. National governments still run Brussels, national machinery is hard to dismantle and institutions, such as the press and the bureaucracy, cannot easily be unplugged. Someone, somewhere always seems to want to hang on to power.

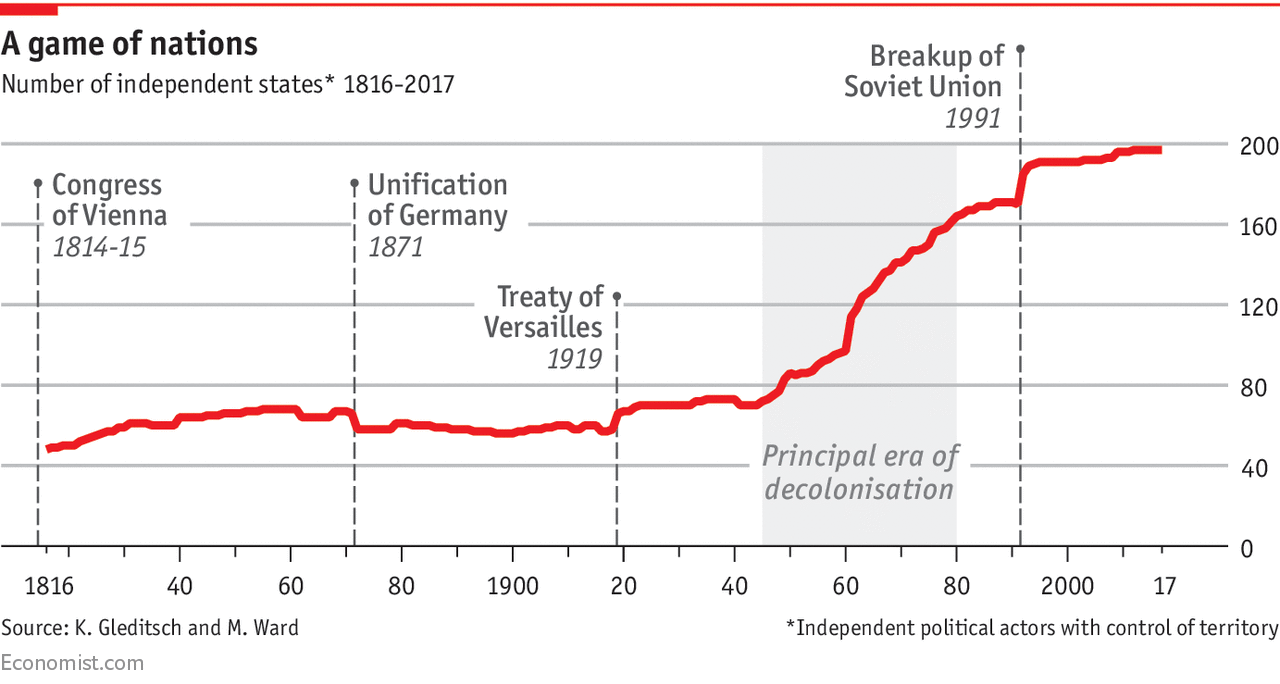

Instead, as empires have fallen apart, Wilson’s principle of national self-determination has spread around the world. The philosophy that nations are sovereign and uniquely able to say what suits them is incorporated into the bedrock of the UN, the Bretton Woods institutions and the whole of international law. Everything else follows from it.

Indeed, nationalism has become so much a part of the backdrop that you hardly notice it—except, as today, when there is a crisis.

TO REACH the Moscow office of Aleksandr Dugin you must first pass through the looking glass. The lift is so small and cramped that you can smell last night’s vodka. On Mr Dugin’s floor you file along endless half-decorated corridors that seem to confound geometry by turning left at every corner. The man himself, tall and ascetic, hair swept back from a high forehead, is a visitor from the 19th century.

His ideas are very influential among Russian nationalists. They are also odd and mystical, involving Vladimir Putin, Russia’s president, as a sort of tsar who subsumes the identity of all Russians. “For us, the tsar is the subject and we are people of the subject,” he says enigmatically. “Human rights are the rights of the tsar.”

Some of his compatriots would differ on this point, Mr Dugin concedes. But he insists that, were he to recast it as Russia’s holy right to be reunited with Crimea, he would command wide agreement. It is always the same: when the West tries to impose what it sees as universal human rights, democracy and the rule of law, it is a denial of the Russian way of life. The West could leave us alone, he says, “but you never do…You think everyone should be like you.”

Here, Mr Dugin is surely right. Since the second world war the West has preached that liberty, law and democracy are universal—something The Economist endorses. Much of the world is not so sure.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Francis Fukuyama, an American political scientist, famously wrote that humanity had reached the end of history, because the only system of beliefs left standing was liberal, democratic capitalism. Led by America, the West energetically promoted this vision, both in its formal foreign policy and through NGOs and think-tanks. Its suasion mostly used example and encouragement, urging supply-side reform, deregulation and privatisation. Occasionally, in the former Yugoslavia, Iraq and Libya, it used force.

But when Communism fell, liberalism was not the Enlightenment’s only remaining legacy. Mr Fukuyama reckoned without nationalism, which he expected to fade away. Just as 19th-century Germans thought Revolutionary cries of liberty, fraternity and equality were camouflage for French conquest, so the leaders of Russia, China, India, Turkey and others have seen the West’s promotion of universal values as a cynical ploy to subvert their rule and their ambitions.

In 19th-century Europe the Germans insisted that only they could say what was best for the Germany they were building. Likewise, today’s nationalists make Dugin-like claims that their values are different from the West’s and just as valid. A new, confident middle class in, say, India and China often agrees. Many of its members want respect, not lectures on how to behave.

The attempt to repel Western universalism has been stunningly successful. The International Criminal Court, which opened its doors in 2002, and the doctrine known as the Responsibility to Protect (R2P), approved by the UN as recently as 2005, were supposed to embody the new, end-of-history consensus that the international community should police crimes against humanity. But the court has been a disappointment and R2P has fallen into disuse. The ethnic cleansing of Rohingya from Rakhine state in Myanmar this year has elicited a lot of noise, but very little action. As famine and disease pick over the carcass of Yemen, torn apart by a pointless war, the world is busy looking the other way.

Once, America would have stepped in. But the champion of universal values has undergone a dramatic change of heart. Rex Tillerson, America’s secretary of state, told his dismayed diplomats this year that his priorities were security and the economy. Promoting American values had, he said, become an “obstacle”.

President Donald Trump could not have been clearer when he addressed the UN’s General Assembly last September: “We do not expect diverse countries to share the same cultures, traditions, or even systems of government. But we do expect all nations to uphold these two core sovereign duties: to respect the interests of their own people and the rights of every other sovereign nation.”

To grasp how much ground Mr Trump has surrendered, consider that two world wars led America’s leaders to conclude they needed to make the world safe for their country. That meant forging a broad-shouldered alliance based on democracy, the rule of law and an open economy. It was the most powerful alliance in history, based on an intense civic nationalism that promoted Western values. By endorsing the world of blood and soil, Mr Trump has tossed aside that common cause. If each country defines its own values, what holds the alliance together?

The new nationalism does not just insist on the differences between countries, it also thrives on the anger within them. Michal Bilewicz, a social psychologist at the University of Warsaw, explains this anger in terms of what his profession calls “agency”—the power to control your own life. Nationalism is determined not by patriotic ardour, he argues, but by self-esteem. Loyalty to the nation combined with confidence and trust favours altruism. By contrast, feelings of frustration and inadequacy tend to lead to narcissism.

Men and women lacking in, or deprived of, agency look to nationalism to assure them that, in their own way, they are as good as everyone else—better, even. It is just that the world does not give them the respect they deserve. They are quick to identify with those they see as on their side and to show contempt for others, Mr Bilewicz says. At the same time they are obsessed by how others see them. Their world is that of Carl Schmitt, a German Nazi and constitutional lawyer, who believed such conflict to be the fundamental stuff of politics, both within nations and between them: “The distinction specific to politics…is that between friend and enemy.” In Schmitt’s view, politics is a kind of civil war. Everything boils down to loyalty.

Here is how altruists contrast with narcissists:

Look to the future—Rake over the past

Positive-sum—Zero-sum

Share—Exclude

Work together—Gang up

Improvement—Struggle

Opponents complement—Opponents are traitors

Immigrants add variety—They threaten our way of life

United by values—United by race and culture.

Altruists acknowledge a chequered past, give thanks for today’s blessings and look forward to a better future—a straight line sloping up across time. Narcissists exalt in a glorious past, denigrate a miserable present and promise a magnificent future—a rollercoaster U-curve, with today in its pit. This geometry explains why nationalist books such as “The French Suicide” and “Germany Destroying Itself” can succeed while appearing to do down the very nation they worship. If you need a rule of thumb for assessing a nationalist movement, ascending ramp v switchback U is as good as you are likely to get.

The citizens of nowhere have a point when they root the new nationalism in economic inequality; but the driving force is not absolute poverty so much as a relative loss of agency. Mr Bilewicz’s narcissistic nationalists feel that the disruptions to the economy caused by globalisation and technological change have increasingly rigged it against them. Their hard work—real or imagined—goes unrewarded while self-serving elites and the minorities who enjoy their favour reap privileged access to wealth and power. Bureaucrats obsessed by political correctness give immigrants jobs, houses and places in local schools, while the nationalist’s loyalty to the nation, which is held to stretch back generations, is rewarded only by sneering and disdain.

The impotence and insecurity felt by large numbers in developed countries shows that an important lesson has been forgotten. In “Ill Fares the Land”, written in 2010 as he lay dying, the British historian Tony Judt described how post-war democracies were transfixed by the fear that fascism or Bolshevism could once again spellbind the masses. Democracy was fragile, they thought; they were determined that the mistakes of 1914 to 1945 should never be repeated. So they tried to ensure that economies grew in ways that benefited all those who participated in them and provided safety nets for those who could not. Karl Marx believed the working class needed a revolution to get justice. Western democracies gave it welfare states and Great Societies instead.

Judt’s argument was that this system was breaking down. He blamed the market reforms of the 1980s for enriching the elite at the expense of the rest and for destroying the sense that everyone is in the same boat. Yet, in some ways, he was not sufficiently pessimistic. In his eagerness to condemn the market-loving Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, who led America and Britain in the 1980s, Judt ignored the ways in which wasteful and unresponsive bureaucracies had, even in their heyday and their European redoubt, frequently failed the people they were supposed to help.

Judt issued a dying warning: “We have entered an age of insecurity: economic insecurity, physical insecurity, political insecurity.” Populist politicians—almost always nationalist—exploit those insecurities. Claiming a special connection to “the people”, they tell and retell their narratives of corrupt elites, crooked immigrants, misleading media and sinister conspiracies. Social media, which amplify outrage, are the ideal vehicle to spread the word. Rodrigo Duterte, president of the Philippines, has a “keyboard army” to purvey his half-truths. Mr Trump uses Twitter to shout his Schmitt-like distinctions between friend and foe. Nigel Farage, of the UK Independence Party, fans grievance and discontent.

Often the populists are from the hard right. Edmund Fawcett, a writer on political philosophy who was on the staff of this newspaper for many years, points out that the right has always rebelled against the creative destruction wrought by progress. Liberals (in the British sense) try to deal with change through tolerance, education, material improvement and ensuring that no set interest ever dominates. Conservatives, however, look to tradition, hierarchy, deference, protectionism and orthodoxy to keep the chaos at bay. Some have never abandoned their belief that only a strong, ethnic culture and a powerful government can keep them safe. Such people are the backbone of the new nationalism.

SOCIAL scientists tell a story about a peasant called Vladimir. One day God comes down to him and says: “I will give you one wish. You can name anything you want and I will grant it to you.”

Vladimir starts to celebrate, but then God lays down a condition. “Whatever you choose,” He says, “I will give to your neighbour twice over.”

Vladimir frowns and thinks. And then he clicks his fingers. “I have it,” he says. “Lord, please take out one of my eyes!”

In a sense, Vladimir was blind all along. Fixated by status, he could not bear to see his neighbour do better than him, even if he had to suffer to prevent it.

Social scientists use Vladimir’s choice to explain the seemingly irrational behaviour of subjects in psychological experiments. But it is tempting to project that same frame of mind onto nationalists obsessed by their own greatness. You might think that the answer to economic insecurity would be schools, roads and other civic improvements, but the new nationalists prefer triumphal arches to cycle lanes. Monuments are a (temporary) remedy for their lack of self-esteem. Nationalism gets in the way of clear thinking, because it turns politics into Schmitt’s contest between friends and enemies, rather than the creation of common projects arrived at from diverse outlooks.

Time and again, nationalists make choices that cause themselves harm. If there are enough Vladimirs, these choices will feed off each other. Nationalist leaders are highly sensitive to their own injured pride. They are less sensitive to the fact that other countries have pride, too. Poland has fallen out with its most important ally, Germany. Turkey is blasting the EU, its biggest trading partner. Venezuela’s pursuit of the Bolivarian revolution has taken the country over a precipice.

In this light, Britain’s vote to take back control from Eurocrats, the European Parliament and the court in Luxembourg looks like an uprising by the English—or rather the English outside London—who opted for Brexit. (The Welsh chose narrowly to leave, Londoners, the Scots and the Northern Irish to stay.)

Fintan O’Toole, an Irish journalist, thinks this uprising showed how the English have refused to accept their decline. The United Kingdom and great-power politics once amplified Englishness: both have now fallen away. The surrender of sovereignty to Brussels felt like another rung on the ladder towards mediocrity. But, says Mr O’Toole, English nationalism is naive. “Wrapped for so long in the protective blankets of Britishness and empire,” he says, “[England] has not had to test itself in the real conditions of 21st-century life for a middle-sized global economy.”

In its negotiations with the remainder of the EU and the rest of the world, Britain will have to surrender sovereignty once again while at the same time coming to terms with its lost influence—evaporated when it decided to relinquish its membership of the EU. Britain never faced up to the hard-nosed calculations about whether Brexit is likely to leave it better off. Anyone who expressed doubts in the campaign was accused of insufficient patriotism. Since the vote, that charge has swollen into full-blown treachery.

Bigger still is what Mr Trump’s nationalism means for the United States. In that speech to the UN General Assembly he described a world in which each country looks out for itself, a “world of proud, independent nations that embrace their duties, seek friendship, respect others, and make common cause in the greatest shared interest of all: a future of dignity and peace for the people of this wonderful Earth.”

A “pluralism of national bigotries”, as one thinker once called such a system, may indeed lead to a stable world. Roger Scruton, a conservative British philosopher, argues that nations find it easier to live side by side than religions do. For peace and security, John Stuart Mill argued, self-determination is necessary.

But is it sufficient? The institutions that shape the world and keep it running smoothly have required an order guaranteed by America, as well as the self-determination of others. Mr Trump’s readiness to walk away from the system could do it permanent harm.

Take, for example, his decision to quit the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) right at the start of his presidency. Throughout the campaign, Mr Trump rubbished the 12-member trade pact as a bad deal for America—partly because he thinks America has more negotiating clout in bilateral deals, partly because he wants to do down his predecessor, who had championed it.

Ditching the TPP was not only bad for America’s economy. It also hurt Asian security. The deal would have created a conduit to channel China’s expansion, aligning it with today’s institutions and removing its incentive to overturn them. Mr Trump said he was acting to make America great again. Instead, he let down its allies and handed China an invitation to shape the world.

Mr Trump’s foreign policy has its episodes of engagement, such as the cruise-missile attack which followed Syria’s gassing of civilians. But it is dominated by structural withdrawals, as from the TPP and the Paris climate-change agreement. Eventually this could leave the world without a leading power for the first time since 1945. Insecurity—instability—would go global. The closest parallel would be 19th-century Europe after the fall of Napoleon. For almost a century Metternich, Talleyrand, Castlereagh and their successor statesmen managed a delicate balance that avoided continental-scale wars even as national fortunes ebbed and flowed.

To re-run that diplomatic feat would be extraordinarily hard. Unlike today’s leaders, 19th-century Europeans came from a single intellectual tradition. Britain, as the strongest power, shifted its weight to ensure that no other country ever thought that it could prevail through war. In the world of 2017 no country is available to play that role. Back then there was no Twitter or 24-hour news, leaving statesmen freer to make concessions over brandy and cigars. Nineteenth-century European powers competed against each other by building empires; that option is no longer available.

The European peace came crashing down in 1914, partly because Germany’s rise led it to outgrow the system holding it back. Today’s peace will also be tested, as America faces up to the need to accommodate an ambitious China. Mr Trump’s promise to Make America Great Again will not make that any easier.

Unlike in the 19th century, some nations have nuclear weapons. That will focus minds on peace. Until it doesn’t.

IT WAS 2pm on October 13th 2017 and 48 people were about to become Canadian citizens. The judge welcoming them to the Ontario Science Centre that Friday afternoon was Albert Wong, himself an immigrant.

In most countries those who are born citizens think that immigrants are lucky to get in. But Mr Wong thanked his 48 new compatriots for the sacrifices they had made in leaving behind their homes. Later Yasmin Ratansi, MP for the local riding, stressed that Canada has expectations of its citizens—to contribute to the community, respect women and obey the law. “You must ensure that Canada is as proud of you as you are of Canada,” she said. Afterwards, when everyone had eaten a slice of cake, some members of the Ojibway nation invited Canada’s newest citizens to join them in a tribal dance that snaked around the meeting hall.

Canada is fiercely nationalistic in its way. Just like any other form of intense nationalism, the Canadian sort can be off-putting. But even though it sometimes strays into smugness and sermonising, Canada has something important to teach an uncertain world.

In emerging countries a growing new middle class wants its own set of civic clothes, not a collection of ill-fitting ideological hand-me-downs from the West. They have yet to decide whether to join the pageant of liberal democracies in a way they think will suit them, or to turn aside and march on alone. In the West nationalists have to choose between looking out and looking in. Will they be sucked into a fascination with triumphal arches, glorious sacrifices and the obsession with loyalty and betrayal? Or will they embrace a civic sort of nationalism instead, comfortable with themselves and the world around them?

Canada hints at a resolution of these conflicts between civic and ethnic nationalism. Its politics gravitates towards cohesion. Michael Adams, who has a new book arguing that the Trump revolution could not have happened north of the border, points out that a Canadian prime minister has to win the cities; and you cannot win the cities by pitching for the white vote alone. He says that what Canadians see in America only reinforces their openness. “We’re global,” he says, “and we’re becoming more xenophilic.”

The country marked the 150th anniversary of its confederation with refreshingly unstuffy and nostalgia-free celebrations. In the capital, Ottawa, they held a skating race on the Rideau Canal, a world-heritage site. A French street-theatre company entertained the crowds with giant puppet-figures. Canada is—belatedly—facing up to its mistreatment of its first nations. A light show at Miwate acknowledged the sacred importance of the Chaudière Falls to the Algonquins and marked the end of their industrial exploitation. Guy Laflamme, the main organiser for the city, admits that Canada still has problems with race. “But,” he says, “we’ve developed a model that’s pretty exemplary.”

That model celebrates difference and rewards collaboration. Canadians like to say that the cold winters forced them to work together to survive. Quebec, where years of anti-French prejudice led to a powerful drive for independence, obliged them to accept that there is room for more than one culture on equal terms. They have a mosaic, not a melting pot. They have found a way to celebrate cultural differences and wrap them in a bundle of all-enveloping tolerance. It is not a choice between cultural exceptionalism and moral universalism, but a benign mix of both.

Towards the end of the citizenship ceremony, Paul Martin, a former prime minister, rose to speak to the people who had come to his country from around the planet. He told them that Canada was now theirs to mould and improve. He congratulated Mr Wong on having the best job in the world. And he spoke about how his own father, as secretary of state in 1967, had opened Canada’s borders to immigrants from outside Europe. “It was the right thing to do then,” Mr Martin said, “and it is the right thing to do now.”

No comments:

Post a Comment