By Jack Thompson

According to Jack Thompson, US grand strategy is at a crossroads. Washington may continue to pursue internationalism, as most of the country’s conservative national security establishment would prefer. However, Donald Trump’s election and his embrace of populist conservative nationalism could mean that the US will turn its back on the liberal world order. Either way, suggests Thompson, the debates currently raging within the Trump administration will do much to determine which direction the US will eventually take, with significant consequences for the global order.

US grand strategy is at a crossroads. Will Washington continue to pursue internationalism, as most of the establishment would prefer, or does the election of Donald Trump and his embrace of populist conservative nationalism indicate that the US is about to turn its back on the liberal world order? The answer will play a significant role in determining the nature of world politics in the coming years.

US grand strategy between 1992 and 2016 was, in retrospect, remarkably consistent. Even though the foreign policy records of the post-Cold War presidents – Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama – differed, sometimes dramatically, they shared fundamental assumptions about international politics and the strategy the US should pursue to maximize the safety and prosperity of its citizens.

Judging from each administration’s National Security Strategy reports – which are mandated by Congress – and other official documents, they all advocated a muscular version of liberal internationalism. This entailed the core objectives of military predominance – albeit paired with a network of security alliances and membership in international organizations – the lowering of trade barriers, and the spread of democracy. In addition, each administration viewed legal immigration as desirable economically and acceptable culturally.

This agenda also served a wider objective – the maintenance and spread of the liberal world order. This policy of enlightened self-interest, with the US benefitting as much as its partners and allies, was consistent with mainstream thinking after 1945. When it came to grand strategy, at least, the truism about continuity in US foreign policy – that there is a lot more of it than change, regardless of which political party was in power – largely held true.

But the election of Donald Trump has thrown into doubt the future of this pattern. The president represents at least a partial break from the post-1945 consensus. In contrast to his predecessors, he espouses a zero-sum philosophy – foreign policy is about “winning” at the expense of other nations. Furthermore, his ambivalence about the liberal world order – and the level of enthusiasm that this has generated amongst his supporters – raise fundamental questions about the future of US grand strategy and the international system.

The US in a Changing World Order

The ascent of Trumpism can only be understood against the backdrop of a rapidly evolving world order. We are witnessing the emergence – or rather the return to – a genuinely multipolar system. Not since before the Second World War has international politics been characterized by such a complicated and varied power structure.

Grand Strategy: an Overview

Grand strategy can be defined, in brief, as a nation’s attempt to coordinate all aspects of its foreign policy – diplomatic, economic, and military – in order to achieve short- and long-term objectives. Perhaps the most notable modern example was the policy of containment that the US and its allies pursued during the Cold War. A useful starting point for understanding US grand strategy is the National Security Strategy. Though these documents are often criticized as products of bureaucratic busywork that lack specifics, as a historical source each NSS offers insights. They can highlight the contemporary context in which grand strategy was being developed – the 2002 NSS can only be understood within the context of the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001, for instance – and the broad themes that administrations hoped to emphasize.

Several aspects of this emerging system require the close attention of US policymakers. The most important is the rise of China. With the world’s largest population and active military and, by some measures, the largest GDP, China is a superpower and – compelled by a fierce nationalism – has begun to act like one. In recent years, it has begun to challenge US interests, especially in the South China Sea. Beijing has called into question US predominance in the world’s most important waterway and begun to undermine Washington’s alliances in East Asia. It has also sought to test US leadership in other realms. Initiatives such as the “One Belt, One Road” project and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership seek to place China at the center of Asia’s economic future.

Another persistent headache for US strategists has been the resurgence of Russia. Moscow’s interventions in Ukraine and Syria, its knack for exploiting the fault lines in NATO, its interference in the 2016 US presidential election, and the growth and modernization of its nuclear arsenal – now the world’s largest – have all served as a reminder that Russia is one of only two countries, along with China, that can challenge the US on a global scale.

Russia’s reemergence has, in many ways, renewed the importance of Europe in US strategic planning. However, it has also called into question the future of the relationship. Though most US analysts believe that Europe will continue to be a vital partner, even optimists wonder how European policy-makers will solve their internal challenges – the Eurozone and migrant crises and Brexit, to name just a few – and play a more active role in world politics, as the US has long demanded.

A more vigorous EU foreign policy is essential for many reasons, not least because the US needs help in confronting some stubborn regional challengers. In spite of vigorous efforts to contain it, North Korea has established a viable nuclear weapons program and will probably soon master the technology necessary to strike the west coast of the US with an intercontinental ballistic missile. In doing so, it has destabilized East Asia. It has further complicated relations with China, which is Pyongyang’s only ally. It has also increased uncertainty about US security guarantees in Seoul and Tokyo, where the fear is that Washington will be less likely to confront North Korea once its territory is under threat. This makes it more likely that South Korea and Japan will seek independent nuclear deterrents.

Thanks to the negotiation of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) in 2015, Iran’s nuclear program is, at least for the moment, less worrisome than that of North Korea. However, its foreign policy is, in some ways, even more problematic. The US considers Tehran to be the foremost state sponsor of terror. In addition, its interventions in hot spots throughout the Middle East, most notably in Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan, have hindered US plans for those countries.

The evolution of the international economy has troubled policy-makers at least as much as geopolitics. Free trade has benefited millions of Americans, especially in urban areas and on the coasts, and contributed to relatively steady domestic economic growth. It has also been an integral part of grand strategy since the end of Second World War, buoying allies and creating an interlocking web of economic relationships that form a cornerstone of the liberal world order.

However, there is also a dark side to expanding free trade (and to its cousin, technological change). Many Americans have seen their incomes stagnate, or their jobs disappear altogether, and inequality is at the highest level ever. This has generated significant opposition to trade liberalization – and immigration – and engendered distrust of the political and economic elite. This is not surprising, because Washington has mostly failed to help those that have struggled to adapt to the globalized economy, and also failed to react constructively to the resulting political backlash.

All of these shortcomings have contributed to a sense that the US is in decline. Whether or not this is true – scholars disagree – is somewhat beside the point. Many, at home and abroad, believe that the US is a fading power, and this perception has important implications for its grand strategy.

Trumpism and Grand Strategy

Though the conservative establishment embraced the foreign policy consensus after the late 1940s, many in the grassroots and on the fringes of the Republican Party never reconciled themselves to internationalism. Over the years, extremists such as Patrick Buchanan harnessed these impulses in passionate challenges to the conservative mainstream. These efforts, though quixotic, prevented the extinction of an alternative worldview – conservative nationalism instead of internationalism; military strength employed unilaterally instead of on behalf of the liberal order; protectionist policies that would ostensibly benefit workers and industry at home, not overseas; and skepticism about expertise and elite leadership.

Trump’s successful presidential campaign reintroduced populist nationalism to the conservative mainstream. He blamed free trade and immigration for the plight of working-class whites, called into question longstanding security alliances, flouted democratic norms, and accused political and economic elites of using globalization to enrich themselves at the expense of the rest of the country. In other words, he rejected the foundations of the liberal world order. As an alternative, he touted a path that maximized the national interest at the expense of other nations – an approach he called “America First”.

Trump’s message was effective, first and foremost, because the domestic political context has shifted dramatically in recent years. That wages are stagnant or falling in real terms is hardly news – this has been occurring for decades – but the extent of the problem was highlighted by the economic recession in 2008. Furthermore, the nation has been growing more diverse for years, but the election of Barack Obama sharpened the concerns of culturally conservative whites about multiculturalism. And many of Trump’s supporters regard the advances of competitors such as China and Russia not as a consequence of multipolarity, but as the result of the alleged fecklessness of previous administrations and their dedication to the liberal order.

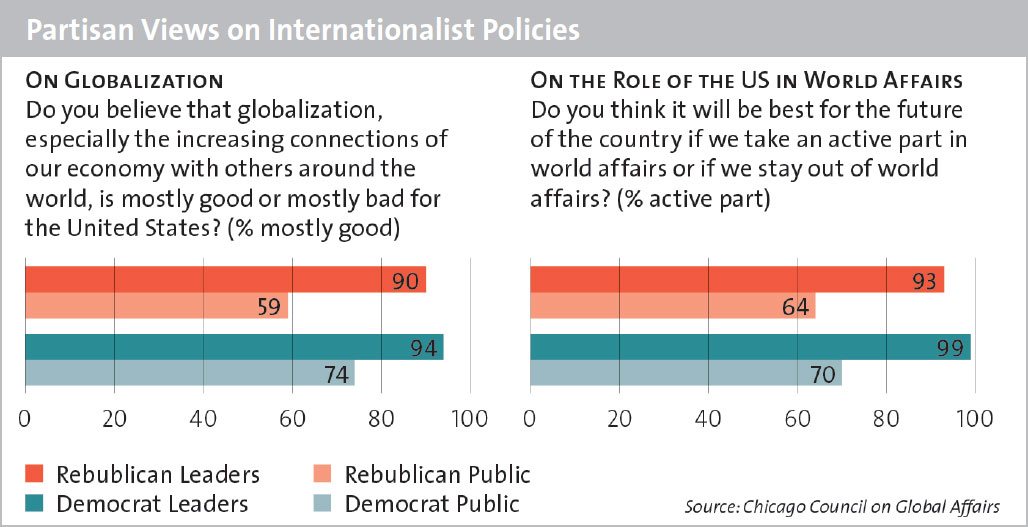

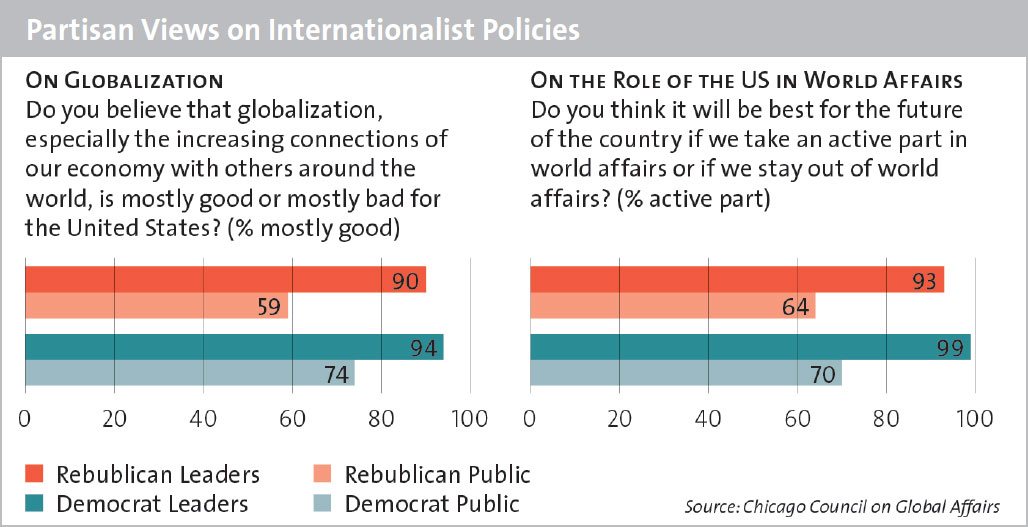

But the extent of the opposition to internationalism should not be overstated. The mainstream of the Democratic Party – though not always the grassroots left – supports policies conducive to maintaining the liberal world order. Even on the right, opposition to internationalism is far from universal. Republicans in business and with university degrees, for instance, tend to be sympathetic to much of the internationalist agenda. Most notably, the conservative national security establishment is almost universally opposed to Trumpism, a fact that is now at the heart of the fight over the future of US grand strategy.

Advantage Nationalists

Trump has made limited headway in implementing his worldview, due in part to the lack of a coherent plan for governing and the fact that some of his key decisions, such as on immigration, are subject to oversight by Congress and the courts.

But perhaps the most important factor in limiting Trump is that conservative internationalists staff much of the administration. Indeed, the vast majority of the Republican Party’s foreign policy establishment espouses internationalism – and many of them are critical of Trumpism. In spite of his reluctance to hire those whose loyalty could be questioned, the president chose several such men for key positions. These figures have fought to maintain at least some internationalist priorities. They have enjoyed some notable successes, including reinforcing the importance of alliances in Europe and East Asia.

However, the influence of the conservative internationalists has been countered by some of the president’s closest political aides, who advocate an extreme version of a nationalist foreign policy. Even after the departure of former White House Chief Strategist Steve Bannon, they remain formidable. Though their efforts to downgrade the importance of relations with the EU and NATO have met with only partial success, they have had more luck in other battles. One is the promotion of protectionism: the Trump administration withdrew from the Trans-Pacific Partnership deal and has signaled its intent to renegotiate the North American Free Trade Agreement. They scored another victory on immigration. The president signed an executive order to ban immigrants from a number of Muslim-majority countries – though this has been challenged in court – and has proposed a reform of the system that would halve legal immigration. The nationalists have also been effective in opposing international agreements, as Trump has withdrawn the US from the Paris climate accord and indicated that he will likely end US participation in the Iran nuclear deal.

However, the influence of the conservative internationalists has been countered by some of the president’s closest political aides, who advocate an extreme version of a nationalist foreign policy. Even after the departure of former White House Chief Strategist Steve Bannon, they remain formidable. Though their efforts to downgrade the importance of relations with the EU and NATO have met with only partial success, they have had more luck in other battles. One is the promotion of protectionism: the Trump administration withdrew from the Trans-Pacific Partnership deal and has signaled its intent to renegotiate the North American Free Trade Agreement. They scored another victory on immigration. The president signed an executive order to ban immigrants from a number of Muslim-majority countries – though this has been challenged in court – and has proposed a reform of the system that would halve legal immigration. The nationalists have also been effective in opposing international agreements, as Trump has withdrawn the US from the Paris climate accord and indicated that he will likely end US participation in the Iran nuclear deal.

More generally, these advisors have succeeded in injecting a note of extreme nationalism into the administration’s rhetoric. Even internationalists in the administration have been affected. H.R. McMaster, the National Security Advisor, and Gary Cohn, the Director of the National Economic Council, co-wrote an opinion piece in The Wall Street Journal that rejected the notion of a “global community” and celebrated realpolitik in world affairs. Such language is consistent with the fact that Trump never refers to democratic values or the desirability of defending the liberal world order. His harsh criticism of close allies, such as Germany, is unprecedented.

The Future of US Grand Strategy

We will have a better sense of the state of the battle between the extreme nationalists and the conservative internationalists later this year, when the administration releases its first National Security Strategy. However, we can already evaluate the extent to which Trump represents a departure from the post-1945 consensus and highlight questions that will bear watching during the remainder of the president’s tenure.

Trump’s election has altered, for the foreseeable future, the nature of US grand strategy by imparting legitimacy to populist conservative nationalism. Prior to Trump, it lurked on the fringes of the Republican Party, resonating with much of the base but shunned by elites. Now, however, nationalists occupy some of the highest positions in government and are busily cultivating opinion leaders who will ensure that these ideas endure. In one sign of the times, the mission of the most influential new policy journal, American Affairs, is the dissemination of conservative nationalist arguments (though it is ambivalent about Trump). (See also American Affairs and U.S. Foreign Policy, 2017.)

Populist nationalism is here to stay. But it is still too early to conclude that the US has reached an inflection point where a majority of the country rejects internationalism. Most of the political establishment abhors Trump’s foreign policy – and that still counts for something. However, in an age of diminishing influence for members of the political elite and a fragmented media landscape, it means less than it would have in years past. Moreover, in a sobering development, even if many elected Republicans clearly distrust or even loathe Trump, the fact that the base of the party remains staunchly supportive of the president has constrained conservative opposition to his policies. In other words, the balance could still tip in either direction.

This matters, because the US faces critical questions. When it comes to trade, for instance, will the protectionist impulse – galvanized by growing inequality and economic anxiety – prevail, or will the US remain a force for liberalization? China, in particular, is a target for protectionists, and if the nationalists have their way, a trade war, with profound implications for the entire world, will likely follow.

In fact, the entire relationship with China is now in flux. The approach of previous administrations – a mixture of carrot and sticks designed to encourage Beijing to integrate peacefully into the liberal world order – has been abandoned, but there is as yet no coherent replacement. If the nationalist approach triumphs, the likelihood of military conflict becomes significantly higher, though thankfully still remaining relatively low overall, thanks in part to the effect of nuclear deterrence. If internationalism reasserts itself, war is still a possibility, but at least there will be more time and opportunity for diplomacy.

Relations with Russia, Iran, and North Korea will also demand attention. The internationalist approach entails several advantages, including the support of allies and international institutions, but it requires patience and the willingness to settle for partial victories. The populist nationalist alternative, which emphasizes freedom from the constraints of alliances and international law and norms, is ill-suited to solving such problems peacefully. If nationalism remains influential, look for more volatility in these relationships. This means policymaking at the extremes – from Trump’s desire to establish friendly relations with an autocratic and revanchist Russia, at one end of the spectrum, to his inclination to end the JCPOA, in spite of its efficacy, on the other. (See also Trump Preparing to End Iran Nuke Deal, 2017.)

Such behavior is worrying for many – not least for Europeans, whose foreign and security policies have long taken US internationalism as a given. A more nationalistic US would damage transatlantic relations, not only affecting specific areas of cooperation – the JCPOA would have been impossible without close US-EU collaboration – but also more abstract ones, such as the common commitment to promoting democratic values.

More broadly, the contest between internationalism and nationalism will have implications for how Americans conceptualize world affairs. Will the US continue to view international politics primarily through an optimistic lens? This was an overarching theme between 1945 and 2016, as successive administrations mostly managed to balance threat perceptions with a conviction that the US and the rest of the world benefited from vigorous engagement. Or will a darker perspective predominate, one that regards interaction with the outside world as more likely to do harm? The debate currently raging in the Trump administration will do much to determine which of these visions prevails, and the result will have consequences for the entire global order.

US grand strategy is at a crossroads. Will Washington continue to pursue internationalism, as most of the establishment would prefer, or does the election of Donald Trump and his embrace of populist conservative nationalism indicate that the US is about to turn its back on the liberal world order? The answer will play a significant role in determining the nature of world politics in the coming years.

US grand strategy between 1992 and 2016 was, in retrospect, remarkably consistent. Even though the foreign policy records of the post-Cold War presidents – Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama – differed, sometimes dramatically, they shared fundamental assumptions about international politics and the strategy the US should pursue to maximize the safety and prosperity of its citizens.

Judging from each administration’s National Security Strategy reports – which are mandated by Congress – and other official documents, they all advocated a muscular version of liberal internationalism. This entailed the core objectives of military predominance – albeit paired with a network of security alliances and membership in international organizations – the lowering of trade barriers, and the spread of democracy. In addition, each administration viewed legal immigration as desirable economically and acceptable culturally.

This agenda also served a wider objective – the maintenance and spread of the liberal world order. This policy of enlightened self-interest, with the US benefitting as much as its partners and allies, was consistent with mainstream thinking after 1945. When it came to grand strategy, at least, the truism about continuity in US foreign policy – that there is a lot more of it than change, regardless of which political party was in power – largely held true.

But the election of Donald Trump has thrown into doubt the future of this pattern. The president represents at least a partial break from the post-1945 consensus. In contrast to his predecessors, he espouses a zero-sum philosophy – foreign policy is about “winning” at the expense of other nations. Furthermore, his ambivalence about the liberal world order – and the level of enthusiasm that this has generated amongst his supporters – raise fundamental questions about the future of US grand strategy and the international system.

The US in a Changing World Order

The ascent of Trumpism can only be understood against the backdrop of a rapidly evolving world order. We are witnessing the emergence – or rather the return to – a genuinely multipolar system. Not since before the Second World War has international politics been characterized by such a complicated and varied power structure.

Grand Strategy: an Overview

Grand strategy can be defined, in brief, as a nation’s attempt to coordinate all aspects of its foreign policy – diplomatic, economic, and military – in order to achieve short- and long-term objectives. Perhaps the most notable modern example was the policy of containment that the US and its allies pursued during the Cold War. A useful starting point for understanding US grand strategy is the National Security Strategy. Though these documents are often criticized as products of bureaucratic busywork that lack specifics, as a historical source each NSS offers insights. They can highlight the contemporary context in which grand strategy was being developed – the 2002 NSS can only be understood within the context of the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001, for instance – and the broad themes that administrations hoped to emphasize.

Several aspects of this emerging system require the close attention of US policymakers. The most important is the rise of China. With the world’s largest population and active military and, by some measures, the largest GDP, China is a superpower and – compelled by a fierce nationalism – has begun to act like one. In recent years, it has begun to challenge US interests, especially in the South China Sea. Beijing has called into question US predominance in the world’s most important waterway and begun to undermine Washington’s alliances in East Asia. It has also sought to test US leadership in other realms. Initiatives such as the “One Belt, One Road” project and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership seek to place China at the center of Asia’s economic future.

Another persistent headache for US strategists has been the resurgence of Russia. Moscow’s interventions in Ukraine and Syria, its knack for exploiting the fault lines in NATO, its interference in the 2016 US presidential election, and the growth and modernization of its nuclear arsenal – now the world’s largest – have all served as a reminder that Russia is one of only two countries, along with China, that can challenge the US on a global scale.

Russia’s reemergence has, in many ways, renewed the importance of Europe in US strategic planning. However, it has also called into question the future of the relationship. Though most US analysts believe that Europe will continue to be a vital partner, even optimists wonder how European policy-makers will solve their internal challenges – the Eurozone and migrant crises and Brexit, to name just a few – and play a more active role in world politics, as the US has long demanded.

A more vigorous EU foreign policy is essential for many reasons, not least because the US needs help in confronting some stubborn regional challengers. In spite of vigorous efforts to contain it, North Korea has established a viable nuclear weapons program and will probably soon master the technology necessary to strike the west coast of the US with an intercontinental ballistic missile. In doing so, it has destabilized East Asia. It has further complicated relations with China, which is Pyongyang’s only ally. It has also increased uncertainty about US security guarantees in Seoul and Tokyo, where the fear is that Washington will be less likely to confront North Korea once its territory is under threat. This makes it more likely that South Korea and Japan will seek independent nuclear deterrents.

Thanks to the negotiation of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) in 2015, Iran’s nuclear program is, at least for the moment, less worrisome than that of North Korea. However, its foreign policy is, in some ways, even more problematic. The US considers Tehran to be the foremost state sponsor of terror. In addition, its interventions in hot spots throughout the Middle East, most notably in Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan, have hindered US plans for those countries.

The evolution of the international economy has troubled policy-makers at least as much as geopolitics. Free trade has benefited millions of Americans, especially in urban areas and on the coasts, and contributed to relatively steady domestic economic growth. It has also been an integral part of grand strategy since the end of Second World War, buoying allies and creating an interlocking web of economic relationships that form a cornerstone of the liberal world order.

However, there is also a dark side to expanding free trade (and to its cousin, technological change). Many Americans have seen their incomes stagnate, or their jobs disappear altogether, and inequality is at the highest level ever. This has generated significant opposition to trade liberalization – and immigration – and engendered distrust of the political and economic elite. This is not surprising, because Washington has mostly failed to help those that have struggled to adapt to the globalized economy, and also failed to react constructively to the resulting political backlash.

All of these shortcomings have contributed to a sense that the US is in decline. Whether or not this is true – scholars disagree – is somewhat beside the point. Many, at home and abroad, believe that the US is a fading power, and this perception has important implications for its grand strategy.

Trumpism and Grand Strategy

Though the conservative establishment embraced the foreign policy consensus after the late 1940s, many in the grassroots and on the fringes of the Republican Party never reconciled themselves to internationalism. Over the years, extremists such as Patrick Buchanan harnessed these impulses in passionate challenges to the conservative mainstream. These efforts, though quixotic, prevented the extinction of an alternative worldview – conservative nationalism instead of internationalism; military strength employed unilaterally instead of on behalf of the liberal order; protectionist policies that would ostensibly benefit workers and industry at home, not overseas; and skepticism about expertise and elite leadership.

Trump’s successful presidential campaign reintroduced populist nationalism to the conservative mainstream. He blamed free trade and immigration for the plight of working-class whites, called into question longstanding security alliances, flouted democratic norms, and accused political and economic elites of using globalization to enrich themselves at the expense of the rest of the country. In other words, he rejected the foundations of the liberal world order. As an alternative, he touted a path that maximized the national interest at the expense of other nations – an approach he called “America First”.

Trump’s message was effective, first and foremost, because the domestic political context has shifted dramatically in recent years. That wages are stagnant or falling in real terms is hardly news – this has been occurring for decades – but the extent of the problem was highlighted by the economic recession in 2008. Furthermore, the nation has been growing more diverse for years, but the election of Barack Obama sharpened the concerns of culturally conservative whites about multiculturalism. And many of Trump’s supporters regard the advances of competitors such as China and Russia not as a consequence of multipolarity, but as the result of the alleged fecklessness of previous administrations and their dedication to the liberal order.

But the extent of the opposition to internationalism should not be overstated. The mainstream of the Democratic Party – though not always the grassroots left – supports policies conducive to maintaining the liberal world order. Even on the right, opposition to internationalism is far from universal. Republicans in business and with university degrees, for instance, tend to be sympathetic to much of the internationalist agenda. Most notably, the conservative national security establishment is almost universally opposed to Trumpism, a fact that is now at the heart of the fight over the future of US grand strategy.

Advantage Nationalists

Trump has made limited headway in implementing his worldview, due in part to the lack of a coherent plan for governing and the fact that some of his key decisions, such as on immigration, are subject to oversight by Congress and the courts.

But perhaps the most important factor in limiting Trump is that conservative internationalists staff much of the administration. Indeed, the vast majority of the Republican Party’s foreign policy establishment espouses internationalism – and many of them are critical of Trumpism. In spite of his reluctance to hire those whose loyalty could be questioned, the president chose several such men for key positions. These figures have fought to maintain at least some internationalist priorities. They have enjoyed some notable successes, including reinforcing the importance of alliances in Europe and East Asia.

However, the influence of the conservative internationalists has been countered by some of the president’s closest political aides, who advocate an extreme version of a nationalist foreign policy. Even after the departure of former White House Chief Strategist Steve Bannon, they remain formidable. Though their efforts to downgrade the importance of relations with the EU and NATO have met with only partial success, they have had more luck in other battles. One is the promotion of protectionism: the Trump administration withdrew from the Trans-Pacific Partnership deal and has signaled its intent to renegotiate the North American Free Trade Agreement. They scored another victory on immigration. The president signed an executive order to ban immigrants from a number of Muslim-majority countries – though this has been challenged in court – and has proposed a reform of the system that would halve legal immigration. The nationalists have also been effective in opposing international agreements, as Trump has withdrawn the US from the Paris climate accord and indicated that he will likely end US participation in the Iran nuclear deal.

However, the influence of the conservative internationalists has been countered by some of the president’s closest political aides, who advocate an extreme version of a nationalist foreign policy. Even after the departure of former White House Chief Strategist Steve Bannon, they remain formidable. Though their efforts to downgrade the importance of relations with the EU and NATO have met with only partial success, they have had more luck in other battles. One is the promotion of protectionism: the Trump administration withdrew from the Trans-Pacific Partnership deal and has signaled its intent to renegotiate the North American Free Trade Agreement. They scored another victory on immigration. The president signed an executive order to ban immigrants from a number of Muslim-majority countries – though this has been challenged in court – and has proposed a reform of the system that would halve legal immigration. The nationalists have also been effective in opposing international agreements, as Trump has withdrawn the US from the Paris climate accord and indicated that he will likely end US participation in the Iran nuclear deal.

More generally, these advisors have succeeded in injecting a note of extreme nationalism into the administration’s rhetoric. Even internationalists in the administration have been affected. H.R. McMaster, the National Security Advisor, and Gary Cohn, the Director of the National Economic Council, co-wrote an opinion piece in The Wall Street Journal that rejected the notion of a “global community” and celebrated realpolitik in world affairs. Such language is consistent with the fact that Trump never refers to democratic values or the desirability of defending the liberal world order. His harsh criticism of close allies, such as Germany, is unprecedented.

The Future of US Grand Strategy

We will have a better sense of the state of the battle between the extreme nationalists and the conservative internationalists later this year, when the administration releases its first National Security Strategy. However, we can already evaluate the extent to which Trump represents a departure from the post-1945 consensus and highlight questions that will bear watching during the remainder of the president’s tenure.

Trump’s election has altered, for the foreseeable future, the nature of US grand strategy by imparting legitimacy to populist conservative nationalism. Prior to Trump, it lurked on the fringes of the Republican Party, resonating with much of the base but shunned by elites. Now, however, nationalists occupy some of the highest positions in government and are busily cultivating opinion leaders who will ensure that these ideas endure. In one sign of the times, the mission of the most influential new policy journal, American Affairs, is the dissemination of conservative nationalist arguments (though it is ambivalent about Trump). (See also American Affairs and U.S. Foreign Policy, 2017.)

Populist nationalism is here to stay. But it is still too early to conclude that the US has reached an inflection point where a majority of the country rejects internationalism. Most of the political establishment abhors Trump’s foreign policy – and that still counts for something. However, in an age of diminishing influence for members of the political elite and a fragmented media landscape, it means less than it would have in years past. Moreover, in a sobering development, even if many elected Republicans clearly distrust or even loathe Trump, the fact that the base of the party remains staunchly supportive of the president has constrained conservative opposition to his policies. In other words, the balance could still tip in either direction.

This matters, because the US faces critical questions. When it comes to trade, for instance, will the protectionist impulse – galvanized by growing inequality and economic anxiety – prevail, or will the US remain a force for liberalization? China, in particular, is a target for protectionists, and if the nationalists have their way, a trade war, with profound implications for the entire world, will likely follow.

In fact, the entire relationship with China is now in flux. The approach of previous administrations – a mixture of carrot and sticks designed to encourage Beijing to integrate peacefully into the liberal world order – has been abandoned, but there is as yet no coherent replacement. If the nationalist approach triumphs, the likelihood of military conflict becomes significantly higher, though thankfully still remaining relatively low overall, thanks in part to the effect of nuclear deterrence. If internationalism reasserts itself, war is still a possibility, but at least there will be more time and opportunity for diplomacy.

Relations with Russia, Iran, and North Korea will also demand attention. The internationalist approach entails several advantages, including the support of allies and international institutions, but it requires patience and the willingness to settle for partial victories. The populist nationalist alternative, which emphasizes freedom from the constraints of alliances and international law and norms, is ill-suited to solving such problems peacefully. If nationalism remains influential, look for more volatility in these relationships. This means policymaking at the extremes – from Trump’s desire to establish friendly relations with an autocratic and revanchist Russia, at one end of the spectrum, to his inclination to end the JCPOA, in spite of its efficacy, on the other. (See also Trump Preparing to End Iran Nuke Deal, 2017.)

Such behavior is worrying for many – not least for Europeans, whose foreign and security policies have long taken US internationalism as a given. A more nationalistic US would damage transatlantic relations, not only affecting specific areas of cooperation – the JCPOA would have been impossible without close US-EU collaboration – but also more abstract ones, such as the common commitment to promoting democratic values.

More broadly, the contest between internationalism and nationalism will have implications for how Americans conceptualize world affairs. Will the US continue to view international politics primarily through an optimistic lens? This was an overarching theme between 1945 and 2016, as successive administrations mostly managed to balance threat perceptions with a conviction that the US and the rest of the world benefited from vigorous engagement. Or will a darker perspective predominate, one that regards interaction with the outside world as more likely to do harm? The debate currently raging in the Trump administration will do much to determine which of these visions prevails, and the result will have consequences for the entire global order.

No comments:

Post a Comment