By Jonathan Hackenbroich and Jeremy Shapiro

According to Jonathan Hackenbroich and Jeremy Shapiro, the global economic picture seems set to improve dramatically in 2018. However, they also predict that a good year of growth will not dampen great-power competition or increase security or stability in the Middle East. But that’s not all. Find out here what other key economic, security, technological and regional trends our authors think could define 2018, as well as what opportunities could open up for Europe.

The liberal world order staged something of a comeback in 2017. Yet despite suffering several election defeats in the year, anti-system parties gained momentum in a variety of countries.

The global economic picture seems set to improve dramatically in the next year. Nonetheless, a good year of growth will not dampen great-power competition or increase security or stability in the Middle East.

Two key issues will signal the direction of US policy under the Trump administration: the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action and North Korea’s nuclear and missile programmes. The United States will need to work closely with allies to contain the North Korean threat.

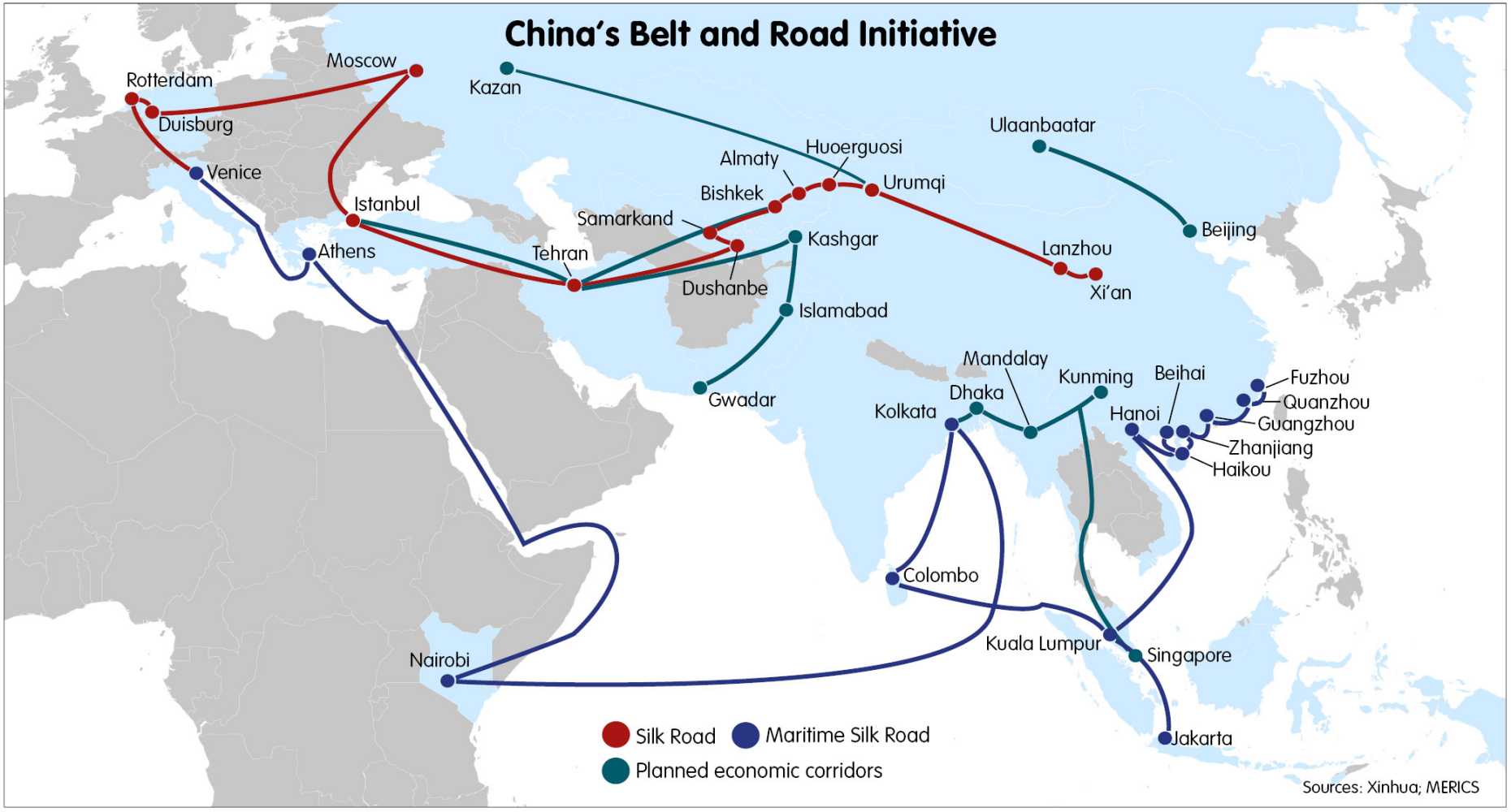

Europeans can work with Beijing to protect international institutions when necessary and possible. But they should have no illusions: they will also have to adopt a more realistic and political approach to China.

Europe has a chance in 2018 to reverse the trend of it falling behind in digital technologies – the area in which economic growth, security, and the preservation of democracy will take shape.

2017: It could have been worse

Prediction is a gloomy business, even in the best of times. It is neither fun nor interesting to predict only good times ahead. By this standard, predictions for 2017 inspired something close to total despair. One can understand why.

In 2016, Britain decided to withdraw from the European Union, America elected a volatile populist to the most powerful position in the world, the Middle East was in chaos, China was on the rise, and Russia seemed poised to further disrupt the global order. With a string of elections in France, Germany, and the Netherlands all threatening to empower populists, it seemed that 2017 might be the year that the liberal world imploded.

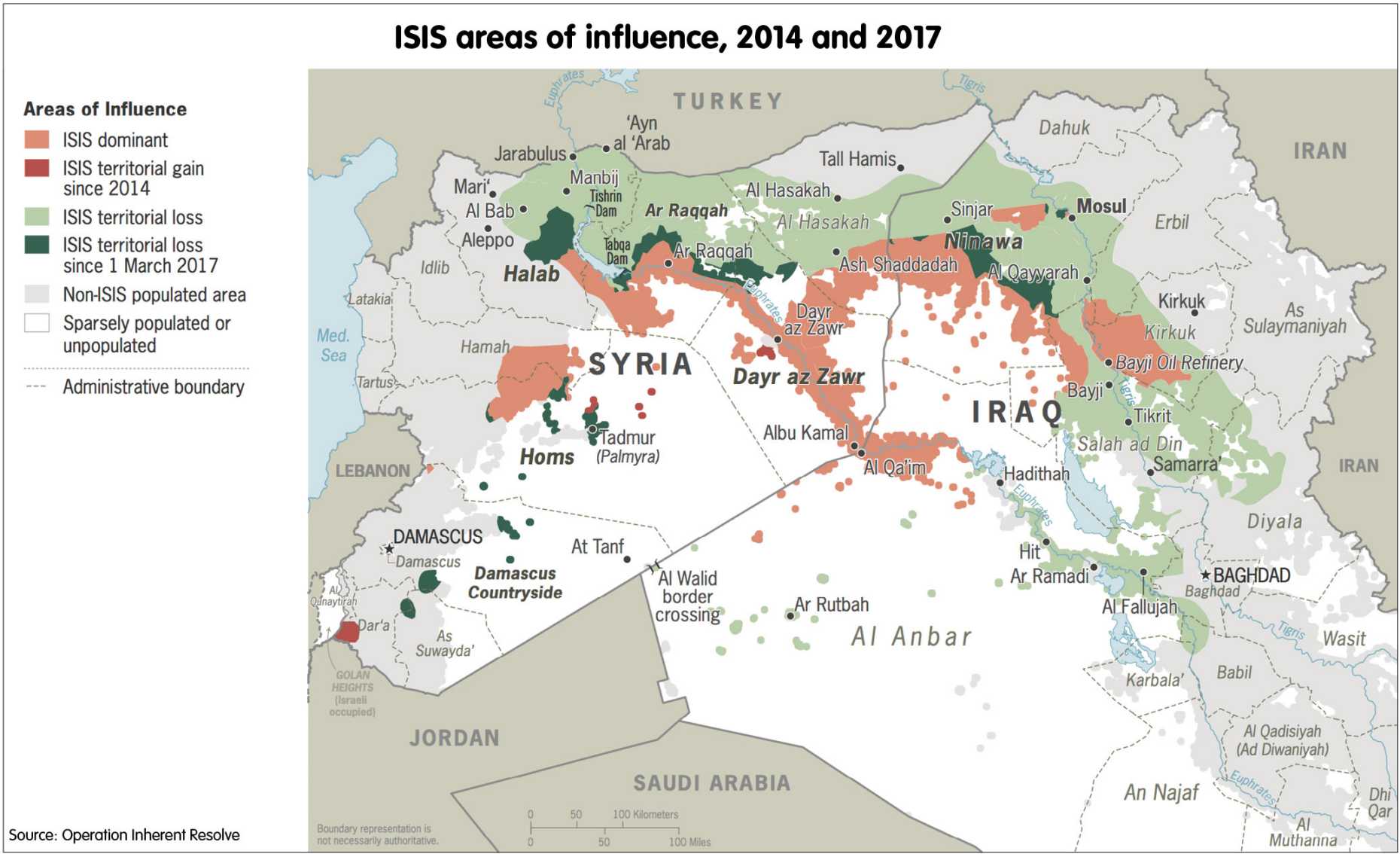

In the event, it was not nearly that bad. Internationalism proved much more resilient than feared. Far from an implosion, the liberal world order staged something of a comeback. In America, Trump seemed to have been contained by his advisers, the courts, and Congress. No new wars broke out in 2017, coalition forces largely defeated the Islamic State group (ISIS) in Syria and Iraq. The elections in 2017 demonstrated that, having seen the disruption caused by Brexit and Trump, voters often opt for more mainstream alternatives. The young, new French president, Emmanuel Macron, even brought new energy to the European-integration process.

Of course, immense challenges remain. We are still living in an angry, populist moment with an international environment characterised by imploding states in the Middle East and increased great-power competition in Europe and Asia. But 2017 reminds us that we have reserves of strength that we often underestimate.

2018: Can populism survive good times?

The question for 2018 concerns whether the positive trends that began in 2017 were merely blips – a “dead cat bounce”, in the language of financial markets – or heralded a more sustained comeback for the mainstream parties.

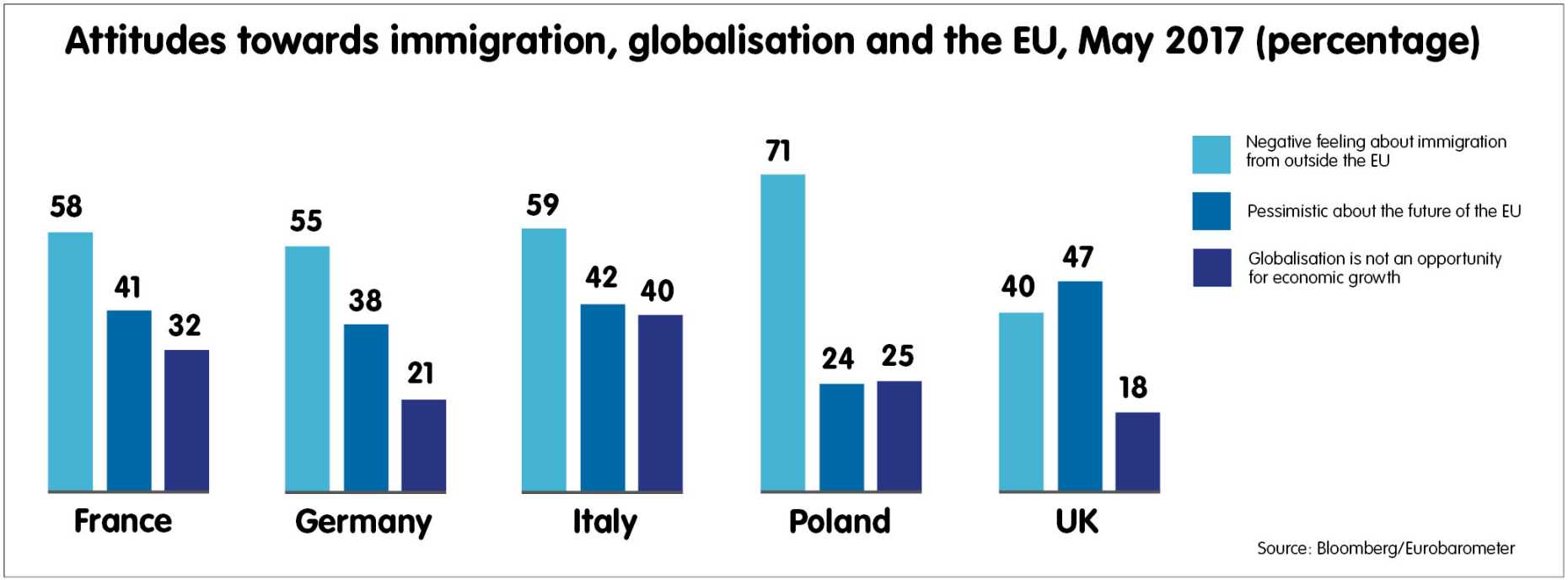

The results of the 2017 elections did not signal an end to the populist moment. Despite the defeats, anti-system parties gained momentum in a variety of countries, including Germany. We continue to see increasing authoritarian tendencies, even within the EU. In 2018, the Italian election will pose another key test.

At the same time, the global economic picture seems set to improve dramatically in the next year, including in Europe and the United States. The populist moment arises from more than just economic factors, but discontent with anaemic growth in personal income over the last two decades lies at its heart. One wonders whether populism’s momentum can survive the coming prosperity.

Regardless, a good year of growth will not dampen great-power competition or increase security or stability in the Middle East. We feel confident that, next year, we will still be able to wring our hands over the rise of China, the threat from Russia, and the tragedies of the Middle East. But if the West gets its house in order in 2018, it may also gain the assurance needed to at least manage these problems.

Regardless, a good year of growth will not dampen great-power competition or increase security or stability in the Middle East. We feel confident that, next year, we will still be able to wring our hands over the rise of China, the threat from Russia, and the tragedies of the Middle East. But if the West gets its house in order in 2018, it may also gain the assurance needed to at least manage these problems.

Much hinges on the nature of the Trump administration. Although America’s influence has receded somewhat in recent years, the country remains the pre-eminent power in the world. In 2017, the White House produced a surprisingly traditional, if often dysfunctional, foreign policy that starkly contrasted with not only Trump’s campaign promises, but also his own statements and tweets as president.

So, the key question for 2018 concerns whether Trump will continue to be hemmed in by Congress and his advisers or else forgo his campaign rhetoric and late-night tweets to finally start to govern. The answer to this question will have an enormous impact on geopolitics in every region of the world.

Major trends

1. Economics: The year of underrated global growth

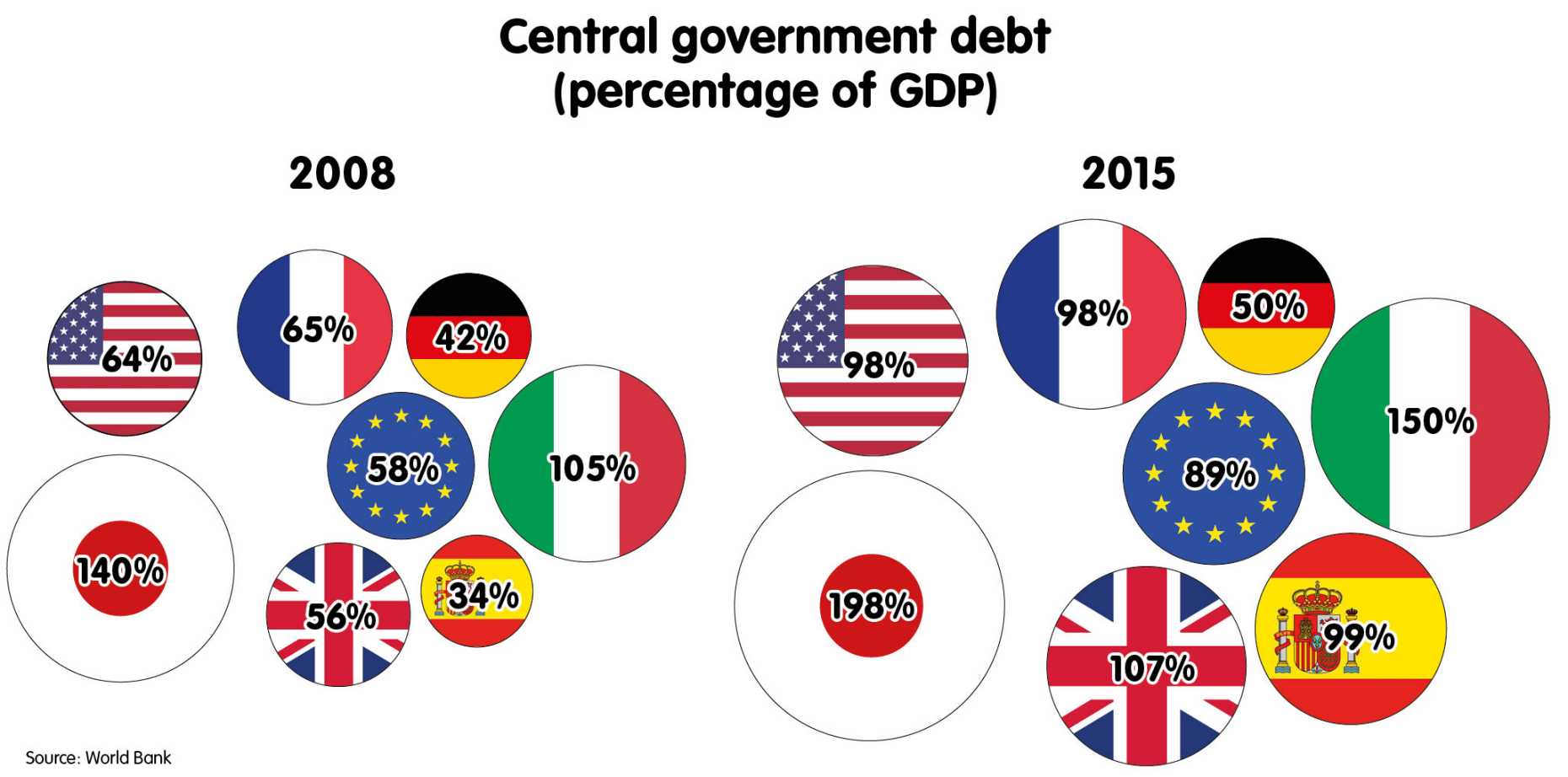

Economically, 2018 promises to be a good year – and it has the potential to be a great year. According to the latest World Economic Outlook by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), global GDP growth is set to accelerate to 3.7 percent, the highest rate since the 2010 rebound from the deep global and economic crisis that unfolded during 2008-2009. The European Commission and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development project a similar pick-up in global growth.

Yet, there is a good chance that these already rosy forecasts still underestimate the momentum. For the first time since 2011, all major country groups are set for a robust, simultaneous upswing, with economic growth rates of at least around 2 percent. The US is already very far into its recovery, with unemployment lower than at any time since the early 2000s. Other regions have just embarked on recoveries or reached the point at which their recoveries have become self-sustaining.

Latin America’s largest economy, Brazil, is climbing out of its deepest recession in decades. Except for in Venezuela, there is for once no acute economic crisis festering in the region. In the euro area, a tepid recovery with unimpressive growth rates is turning into a fully fledged upswing as increases in domestic demand beget capital expenditure and consumption, further boosting this demand. China’s economy has slowed marginally, but there is no reason to expect growth rates to drop dramatically from their current pace of around 6 percent.

In comparable scenarios in the past, professional forecasters have often underestimated the self-sustaining momentum of the business cycle. It is likely that they are doing so again now – especially given that, since the crisis, observers have become accustomed to a dismal growth outlook in much of the world, including the euro area, and are thus reluctant to forecast the kind of growth rates experienced before 2008.

At the end of 2017, there is little indication of purely economic tensions that could derail the global upward momentum. Monetary policy is still expansionary in the largest advanced economies. While the US Federal Reserve has started to tighten monetary policy somewhat and to slowly increase interest rates, most forecasters see interest rates remaining very low by historical standards in 2018.

The European Central Bank has even hinted that, while phasing out its quantitative-easing programme over the coming year, it will wait until 2019 to raise interest rates. Inflation is still subdued and there are no signs of bottlenecks in the major economies or of a sudden jump in inflation.

Austerity, which did so much damage to the European growth outlook earlier this decade, is a thing of the past. In the US and some important European countries, such as Germany, the political situation hints that 2018 will bring fiscal expansion even if their economies are already growing robustly.

As austerity mostly weighed on the European economic outlook, the largest improvements are likely to be seen in the euro area. The eurozone architecture remains incomplete, with key euro members Germany, Italy, and France still in disagreement on how to complete the currency union. But the positive effects of the strengthening recovery now mostly conceal these problems – a rising tide hides all rocks.

Strong nominal GDP growth means that debt-to-GDP ratios will soon fall. This growth, coupled with low interest rates, will allow more companies to continue to service, or resume servicing, their debt, which in turn will bring down the share of non-performing loans in banks’ portfolios. With healthier balance sheets, banks are more likely to extend loans to the rest of the economy, further boosting the recovery.

There remains the possibility that political upheaval will spill over into economics. For the euro area, the risk is that a political force fundamentally opposed to the common currency might gain power in a member state, triggering capital outflows and a return to a fully fledged euro crisis. Current polls in the countries most at risk in 2018 (especially Italy) predict that anti-euro parties will lack the support needed to form new populist governments. But polls have become increasingly unreliable in many countries in the past few years, so this risk should be monitored.

In contrast, many political risks might be less significant than sceptics believe. For example, the possibility of a minority government, a dysfunctional coalition government or even repeat elections in Germany (Europe’s current economic and political powerhouse) will only have limited downsides for the country’s macroeconomic outlook.

A developed country with an experienced army of civil servants can do fine economically without any party having a clear majority in parliament. Spain, after all, staged an impressive recovery from the euro-crisis recession during the first half of 2016, even as its political class struggled for months, in vain, to form a coalition government. Paradoxically, in Germany, a weak government might boost the economy in the short term. The caretaker government might implement a slightly expansionary fiscal policy to allow all coalition partners to realise some of their pet projects, fuelling the recovery in Germany and its neighbours.

For Europe, another risk is a no-deal Brexit in which the United Kingdom leaves the EU in chaotic fashion. While it is true that Britain would suffer most in such a scenario, the country is a sufficiently important trading partner for the rest of the EU that the event would cause significant economic harm to the continent. However, even if such a scenario finally materialised, the EU would only feel the economic consequences after 2018. Both sides will continue negotiating for as long as possible to prevent such a scenario; companies will bet that European negotiators can come up with a creative way to prolong the deadline, as they have done at crucial moments in the past.

For the rest of the world, a major, oft-mentioned political risk with macroeconomic consequences is that Donald Trump will try to whip up his base in the run-up to the midterm elections in November by implementing even more populist trade policies. One possibility is that he will follow through with his threat to pull the US out of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), blaming his action on insufficient progress in talks to reform the deal with the Mexican and Canadian governments. As some of Trump’s advisers have advocated, this might even serve as a prelude to a US withdrawal from the World Trade Organization’s dispute-settlement system.

Yet, while 2018 is set to be a good year economically, the smooth sailing will not continue forever. More economic risks are likely to materialise towards the end of the year. Going into 2019, the world’s central banks will have to show how they manage the balancing act of slowly tightening monetary policy without strangulating the economy. But this will only become a serious issue in 2019. Until then, let’s enjoy the good times as long as they last.

2. International security: a tough year ahead

Good economic times in 2018 will probably focus attention on global security problems, which have deepened in recent years and show little sign of improvement.

The fight against terrorism leads the list of concerns. Even though 2018 will see ISIS relinquish the remaining territory in its control, the fall of its so-called caliphate will not end the terrorist threat. Not only will ISIS activity likely continue to morph into an insurgency in both in Iraq and Syria, but the global terrorist threat will also evolve. Foreign fighters returning home may present new dangers. We may also see the emergence of new areas of operation or even a post-ISIS reorganisation of the jihadist galaxy. In any case, jihadist terrorist groups will remain active, and continue to attract recruits, in regions from the Sahel to south-east Asia.

The fight against terrorism leads the list of concerns. Even though 2018 will see ISIS relinquish the remaining territory in its control, the fall of its so-called caliphate will not end the terrorist threat. Not only will ISIS activity likely continue to morph into an insurgency in both in Iraq and Syria, but the global terrorist threat will also evolve. Foreign fighters returning home may present new dangers. We may also see the emergence of new areas of operation or even a post-ISIS reorganisation of the jihadist galaxy. In any case, jihadist terrorist groups will remain active, and continue to attract recruits, in regions from the Sahel to south-east Asia.

Although terrorism will persist in absorbing much international attention, inter-state tensions present a greater danger in 2018. Currently simmering crises – from the nuclear crisis in North Korea to the still-not-frozen conflict in Ukraine, to various conflicts in sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East – may erupt into full-blown wars or humanitarian catastrophes.

The struggle to protect international security in 2018 will be less about achieving military victory than figuring out how to make such victories endure. From Afghanistan to Mali, European and other Western powers have in recent years mostly proved unable to turn their military advantage into sustained political solutions. Despite rising awareness of the need for better strategies to “win the peace”, there has been little progress on how to do so. Of course, this challenge is not limited to the West – as Russia is likely to experience in Ukraine and Syria.

In 2018 the global security environment will also be marked by non-military threats beyond terrorism. Cyber warfare is likely to remain a significant concern, as it has proven its effectiveness and presses at the core of Western societies’ ambition to remain open and democratic. There will also be other major non-military security concerns, particularly migration. Many countries that receive migrants will continue to securitise the issue – sealing their borders and deporting people who have entered illegally, among other measures – despite the growing and visible shortcomings of this approach.

More broadly, we expect to see a growing international security vacuum in 2018. Since the election of Trump, US foreign policy has a shown a degree of unpredictability and dysfunctionality that is destabilising the international security system. Regardless of the pragmatism of some key members of the US administration, Washington is likely to continue to sow uncertainty about its willingness to act as a guarantor of stability – and might even contribute to further instability in, for example, its relations with Iran.

No obvious successor will fill this vacuum. Russia seems mostly interested in maintaining its role as a spoiler in the current security order. China, even though it wants to increasingly cast itself as a security provider, remains focused on its national security and will be wary of expanding its global responsibilities. Europeans, even if they succeed in their goal of raising their defence profile, will remain limited in their collective ability to provide security beyond their territory.

As a consequence, the international security architecture will be further weakened. Regional powers will feel that they have greater freedom to escalate local disputes, following the example of Saudi Arabia in Yemen. Increasing divides between great powers mean that the multilateral system will remain blocked and multilateral missions for peacekeeping and humanitarian assistance will be increasingly starved of funds. States will also take advantage of the vacuum to contest key international norms: the nuclear non-proliferation regime, the ban on use of chemical weapons, the protection of civilians, and the sanctity of territorial integrity.

How governments will respond

In the face of these security challenges, governments will not stand still. Some responses are already evident.

Increasing government regulation of technology infrastructure: major threats to the technologies that enable modern life have become a critical security concern. The nature of some of these technologies – dual-use, decentralised, connected, and global – will only increase the need to expand policy responses beyond technological issues to include their environment. New technologies have turned the media and domestic civil society broadly into areas of security contestation. Governments will increasingly demand that the private sector collaborate with them to provide protection from asymmetric threats, regulate behaviour, and prevent an excessive diffusion of technologies (including to non-state actors and even individuals).

Eroding the distinction between internal and external security: this trend has been apparent for several years, but it is far from having reached its full potential to transform security and defence policies. The distinction between internal and external security will surely continue to erode, both because of the evolution of the threats, and because of the limitations of current policies – as demonstrated by, for example, the growing discussion in France about the operational shortcomings and unsustainability of the military presence in the streets.

Growing efforts to increase societal resilience: resilience will also continue to grow in importance as an aspect of security and defence policy thinking. The debate will spread from a broad social and political discussion – on issues such as whether terrorist groups’ ability to generate fear will increase, and the impact of Russian influence operations – to more precise topics, such as attention paid to victims or resilient information systems. This debate will occur not just within governments, but also at the level of private companies, local governments, and civil society generally.

Finding creative new mechanisms for international cooperation: In the rather bleak context outlined above, a silver lining could be that, faced with a hardened security environment, international cooperation makes a comeback out of necessity. Indeed, necessity is already a key source of the current European momentum on defence integration.

3. Technology: quantum leaps, learning machines, and robots that leap and learn

Three technologies stand out for their capacity to finally realise some of their potential and change the world in 2018. They are quantum technology, artificial intelligence, and robotics.

Quantum technology: both hype and reality on the progress of quantum technology will continue to rise as developments accelerate, but the discipline will remain poorly understood outside the scientific community. In August 2016, China made headlines around the world for launching the world’s first quantum-communications satellite. The satellite proved in July 2017 that particles can remain linked in a quantum state at a distance of more than 1,200km.1 Hailed as a major step towards unbreakable encryption, “quantum everything” has since become the world’s least-understood buzzword.

Progress in the field of quantum technology is indeed both slower and faster than many people tend to realise, in the sense that much is being accomplished but there is still a long way to go. For instance, IBM announced in November 2017 that it had created a 50-quantum-bit (qubit) prototype computer with double the coherence time of its older, 20-qubit machine.2 As MIT Technology Review writer Russ Juskalian explained, “the top supercomputer systems can currently do all the same things that five- to 20-qubit quantum computers can, but at around 50 qubits this becomes physically impossible”.3 In other words, we are still at least 5-10 years away from building quantum computers that work on an industrial scale, but both governments and companies are engaged in fierce competition in the field.

Based on the success of its satellite, China announced a plan to create the world’s first unhackable computer network.4 In the US, meanwhile, government research agencies are aiming to create the first quantum key distribution network and funding research into logical qubits, coherent superconducting qubits, and error-free quantum computing.5 The European Commission’s €1 billion quantum project is slowly taking shape.6 With IBM, Google, Microsoft, Intel, and several promising start-ups working on quantum technology, 2018 is likely to witness several technological breakthroughs on our journey into the quantum age.7

Artificial intelligence and machine learning: artificial intelligence and machine learning are intertwined and naturally progress in lockstep. One can see why by looking at the difference between Google’s AlphaGo Zero and Microsoft’s Tay.

Tay, a bot on Twitter designed to learn to understand conversation, lacked an effective method for adapting to the medium. As a result, the Twittersphere turned it into a racist homophobe within 24 hours of its launch in March 2016.8 AlphaGo Zero, an artificial-intelligence program designed to master the game of Go, applied reinforced learning for the first time by playing against itself and utilising search algorithms to predict moves. Through this approach, the programme freed itself from the constraints of human knowledge and essentially learned from itself. By October 2017, AlphaGo Zero had learned to become arguably the best Go player in the world in just 40 days.9

As neural-network software progresses and machine-learning techniques become more refined, the goal of creating artificial intelligence is coming ever closer. Capsule networks are one of the latest trends in artificial intelligence and machine learning. The idea behind these networks is to bring artificial-intelligence systems’ capacity to understand their surroundings closer to that of a human toddler. Instead of feeding the system a growing quantity of data on objects viewed from different angles in different positions, capsule networks track various parts of an object and their relative positions in space. In this way, the networks can recognise when an apparently new object is actually a known object seen from a different view.10

Given the progress there has been in artificial intelligence and machine learning, these technologies elicit a vast range of predictions from different observers. Russian president Vladimir Putin perhaps kicked off the artificial-intelligence race between nation states in September 2017, when he noted that “whoever becomes the leader in this sphere will become the ruler of the world”. Tesla’s Elon Musk warned that the “competition for AI superiority at national level [will] most likely cause [World War Three]”.11 But Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg denounced Musk’s warning as “pretty irresponsible”, and Google’s head of search and artificial intelligence, John Giannandrea, declared that he is “definitely not worried about the AI apocalypse”.12 Whatever the military adoption and future of artificial intelligence may be, 2018 will most likely be a year in which we take a leap into the unknown.

Robotics: robotics is a wide field within which progress varies across domains. For instance, Saudi Arabia awarded honorary citizenship to Sophia, the first humanoid robot, in late October 2017.13 The following month, Atlas, a robot created by Boston Dynamics, leaped between boxes before turning round and performing a backflip. This was in marked contrast to the numerous failures of machines at the Robotics Challenge held by the US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) in 2012-2015, or that of Honda’s Asimo, which fell from a set of stairs 11 years ago. As Paul Miller, a writer at the Verge put it, “there was a time before Atlas could do backflips, back when robots were for factories, bomb disposal, vacuuming, and the occasional gimmick, and none of the useful ones were humanoids. Now we’re living in an era where humanoid robots are apparently as agile as we are. So, what will they be used for? It’s time to get out the popcorn.”14

Robotics, and similar areas of technology development, also provide a real opportunity for Europe. If Macron can push through his idea of a European version of DARPA, the next Robotics Challenge could take place on European soil, with European know-how and technology.15

Regional overview

1. Europe: the populist challenge

Since the twin shocks of 2016 – the Brexit vote and the election of Trump – the European political landscape has changed dramatically. 2017 has been about learning to live with this change. Europe’s mainstream parties have veered between euphoria after elections in the Netherlands and France, which strong populist candidates lost, and panic after those in Austria and the Czech Republic, which populists arguably won. But these mood swings often miss the point: the new politics is not about battles that can be won or lost at elections. We would do better to understand the outlook for 2018 through three longer-term trends likely to continue to shape European politics over the coming years.

More fragmented politics: European populism is multifaceted and specific to the various national contexts in which it exists. In some countries, it is anti-EU and rooted in economic nationalism. This applies to, for example, the UK Independence Party and other elements in the “hard Brexit” campaign in the United Kingdom. In other contexts, it is regionalist – as with Catalan separatist parties in Spain and Lega Nord in Italy. These parties are often critical of EU policies, but supportive of the project as a whole. Elsewhere, populism takes the form of nostalgic, nativist nationalism such as that of the Front National in France, or a rejection of bureaucracy in favour of a businesslike approach to the challenge of globalisation, as practised by the Czech Republic’s new prime minister, Andrej Babis. In some ways, the picture is so diverse that the catch-all label of ‘populism’ is less and less useful to describe what is going on across the EU.

However, these movements collectively signal that more extreme political ideas are gaining influence across Europe, and that populist parties are eroding their mainstream rivals’ dominance of the electoral system. In 2018, five member states will be led by governments representing these views, with the new coalition in Austria and the new Czech government joining the governments of Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia.

But even where they do not have parties with relatively extreme views in government, many key EU states will have to work with far smaller governing majorities in 2018. They will have to listen and respond to the worldview of populist, extremist, or nativist political groups from outside government. One of the clearest examples of this is the UK since prime minister Theresa May held snap elections in June 2017. There is also a risk that a similar dynamic will emerge in Italy, which will hold national elections on 4 March 2018.

The largest German parties – which all lost seats in the September 2017 Bundestag elections – are also struggling with this reality. The far-right Alternative für Deutschland and far-left Die Linke vote combined means that around 20 percent of the Bundestag is now made up of extreme parties that the centre will not join in a coalition. But with a smaller majority for the Christian Democratic Union/Christian Social Union, and the vote share split more evenly between other large parties, the process of forming a coalition between mainstream groups has become more complex and looks unlikely to be completed during the first quarter of 2018.

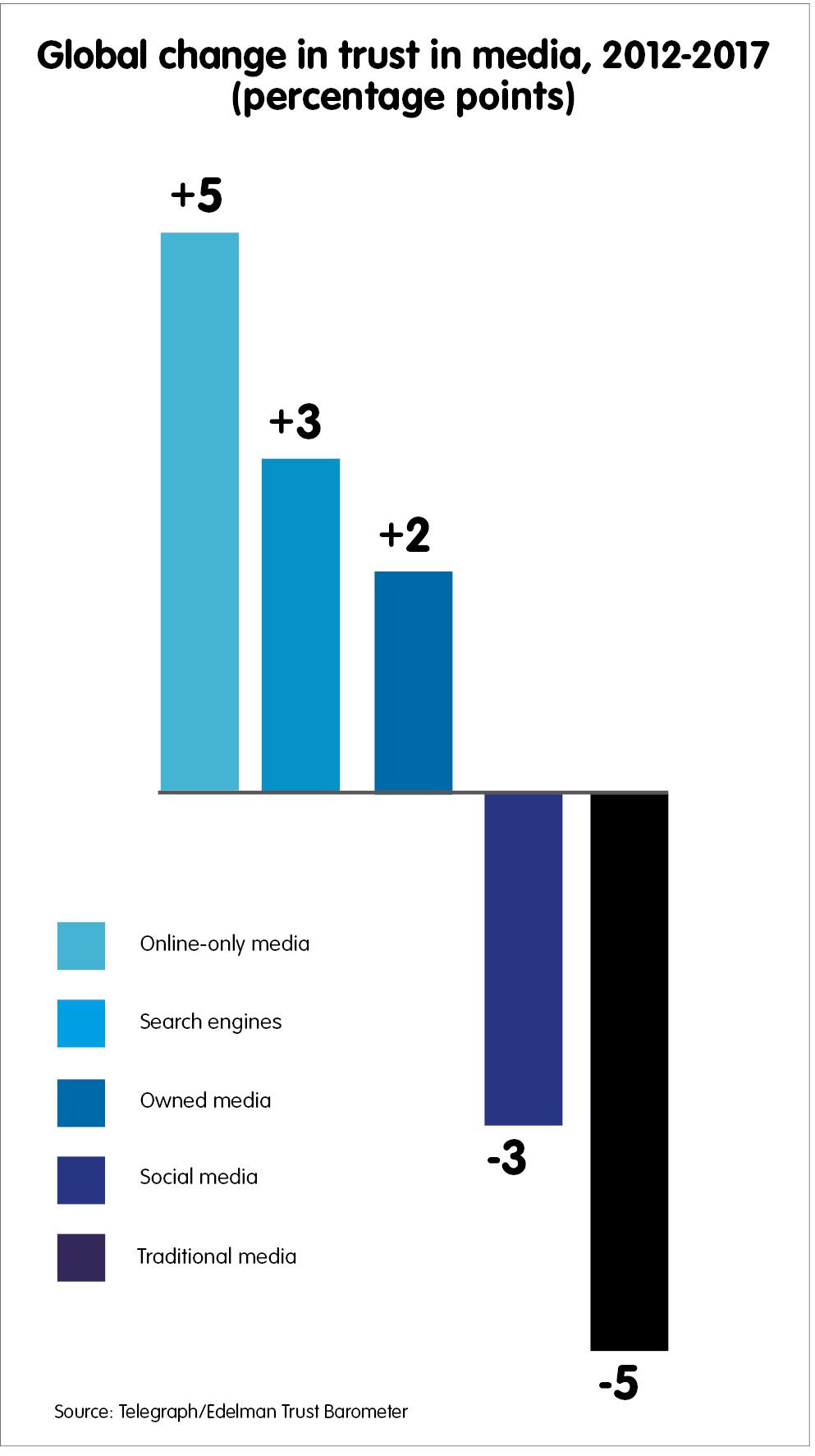

The growing normality of electoral support for extreme ideas has been exacerbated by the role of social media in news consumption, and the manipulation of this process by states, particularly Russia. Some level of media manipulation with traceable links to Russia has been present in every European election in 2017, and looks set to continue as part of Russia’s overall effort to weaken, divide, and disrupt the West.

For policymakers, this trend has underlined the interplay between foreign policy and intra-European politics. But the effect on voters is more complex. Security is one of the primary issues driving the way that people vote, yet it is approached in many parts of the European media through the prism of protecting citizens within Europe, thereby reinforcing the nativist policies of the far right and, increasingly, mainstream parties. In the coming years, governments may become less willing to defend an internationalist vision in their foreign, defence, trade, and development policies when large parts of the electorate increasingly question the link between this vision and their security.

Growing support for more populist and nativist political movements also raises direct questions about the future of the European project itself. Scepticism of the EU is strong in many of these movements. With the European Parliament election scheduled for 2019, there is a distinct possibility that the influence of anti-EU parties will grow even further, increasing the danger that EU institutions may start to disintegrate from within.

At the national level, the 2017 French presidential elections demonstrated that, when pushed, the French people were willing to put the values of the Fifth Republic above politics. The front républicain (a collective vote against the extreme candidate who contravenes the values of the French republic) came into play in the second round of the elections to ensure that Marine Le Pen failed to win the presidency.

No such safety net exists at the European level – indeed, a “front européen” seems entirely implausible in the current political environment. And yet, Brexit, the tacit acceptance of Hungarian and Polish governments with increasingly authoritarian tendencies, and the improving performance of Eurosceptic parties in national elections together create a picture that begins to look threatening to the project as a whole.

Migration: migration is the second issue that will continue to be a major driver of European politics in 2018. Throughout 2017, large numbers of people have arrived in EU countries – with a spike in those reaching Italy via north Africa in summer, and renewed pressure on the western Balkans route in autumn 2017. It is likely that in 2018 there will be renewed political tension around migration in the Balkan states, due to an increased flow of people and the response of the probable new coalition government in Austria – members of which ran on a platform of tightened border controls.

Although tensions in the EU-Turkey relationship have grown throughout 2017, the 2016 deal between the two sides on managing refugee flows from Syria and the readmission of failed asylum seekers has held. In 2018, EU governments will pursue the “migration compact” approach to policy that led to the EU-Turkey deal. This approach combines border management and overseas migration-processing centres with readmission agreements with third countries.

Although tensions in the EU-Turkey relationship have grown throughout 2017, the 2016 deal between the two sides on managing refugee flows from Syria and the readmission of failed asylum seekers has held. In 2018, EU governments will pursue the “migration compact” approach to policy that led to the EU-Turkey deal. This approach combines border management and overseas migration-processing centres with readmission agreements with third countries.

As signalled in the Paris summit on migration in autumn 2017, Macron intends to answer German chancellor Angela Merkel’s call for a more Europeanised approach to managing migration, and for France to play a more visible role on this front. If Merkel emerges as the leader of a fragile coalition, or even a minority government, she will be under increased pressure to show that Germany is not taking responsibility for migration management alone.

The Franco-German motor: cooperation on migration forms part of the third trend that will shape the EU picture in the coming years, with efforts from Paris and Berlin to restart a Franco-German motor at the centre of the EU project. Under increased pressure from extreme political movements across Europe, there is a renewed determination among core member states to show that the EU can be effective, and can deliver on issues of concern to voters – partly through flexible cooperation. The November 2017 agreement to launch a system of permanent structured cooperation (PESCO) on defence was a declaration of intent, designed to bring this commitment to life and lay the groundwork for concrete projects.

But beyond this top line goal to cooperate flexibly, member states will struggle to find compromises on such projects. “Flexible union” has multiple goals: from facilitating the delivery of tangible projects, to capitalising on common interests between member states, to preventing the creeping erosion of the EU through inaction in the face of difficult decisions, to paving the way for future broader cooperation. However, there is unease among non-core EU states about the motives of flexible cooperation, stemming from fear of being left behind or of facing the consequences of unwanted decisions.

Even at the centre of this initiative, the road ahead does not appear to be smooth, with so much uncertainty about the kind of government that will emerge from post-election coalition talks in Germany. The fears and tensions around the ambition for a more flexible Europe are likely to colour relationships between member states for years to come.

2. United States: the Trump distraction

2017 was the year of Trump, in the US and, arguably, the world. In the first year of his presidency, Trump sucked up nearly all media oxygen and became the most talked-about person in the world.

His undiplomatic and unconventional rhetoric, often dispensed in the wee hours of the night in dyspeptic tweets, roiled domestic politics in the US, and geopolitics throughout the world (as the rest of this survey makes clear). As the year ends, he continues to generate controversy on subjects as diverse as his campaign’s alleged collusion with Russia in the run-up to the elections, the proper decorum during the national anthem at American football games, and the penalties for shoplifting in China.

After a year of this, however, it seems a great deal of this controversy is merely a distraction. Trump is governing as he campaigned. His only interests remain himself, his political standing, and perhaps golf; he shows little interest in ideology, policy, or – god forbid – implementation. He has mostly left the troublesome details of governance to subordinates, many of whom do not share his views on key issues such as Russia or Afghanistan.

Broadly, the result has been incoherence and a lack of achievement. The first year of Trump’s presidency, generally the most productive period in any presidency, has few accomplishments. He has failed to find a working relationship with the Republican majority in Congress and only very slowly filled the key positions in his administration.

Partly as a result, of the three major legislative initiatives planned for the first year – the repeal of Obamacare, an infrastructure bill, and tax reform – only tax reform came to fruition. Reform of Obamacare failed to pass Congress and the infrastructure bill never even came up. Trump’s immigration reforms remain stuck in the courts and he has not started to build a wall along the US-Mexican border as he repeatedly promised during the campaign.

Meanwhile, his administration is mired in multiple scandals and dogged by a special counsel that is investigating his campaign’s collusion with Russia. The counsel has already indicted a top Trump aide, convicted a lesser one, and arranged for a plea bargain with Michael Flynn, a former national security adviser. More indictments will likely follow in 2018. Impeachment remains a possible outcome of the investigation, but for that to happen before the November midterm elections would require new and truly explosive revelations.

In foreign policy, presidents typically enjoy more freedom of action than they have at home. Trump’s rhetoric, even when it has been mostly bluster, has sometimes had a direct impact. He engaged in a war of words with North Korea’s leader, Kim Jong-un, over the country’s nuclear and ballistic missile programmes that has dramatically raised tensions and the threat of war in the region. In April, he launched a cruise missile attack against an airbase in Syria in response to the Assad regime’s use of chemical weapons. And he has withdrawn the US from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade effort and the Paris Agreement on climate change.

These are important effects, but they remain much less dramatic than those that Trump promised during the campaign and that his rhetoric since has implied. Trump has not withdrawn the US from NAFTA, engaged in a trade war with China or Germany, abandoned NATO or the US-Japan alliance, torn up the Iran nuclear deal, nor established a strategic partnership with Russia.

Beneath the Twitter broadsides, his foreign policy in the first year has broadly conformed to the norms of previous Republican administrations (with the notable exception of trade policy). This reflects the fact that much of his cabinet consists of experienced generals and members of the Republican foreign policy establishment. US officials abroad regularly tell their counterparts not to pay any attention to what the president says or tweets. They prefer others to judge US foreign policy by its actions.

Will Trump be Trump?

The question for 2018 is whether this bizarre situation can or will continue. As the November 2018 congressional elections approach, Trump will face a growing political dilemma. He has very low approval ratings (in the range of 35-40 percent) for this point in his presidency, in part because he has made little effort to move to the centre and win over people who did not vote for him in the election. He has instead chosen to fire up his hardcore supporters with constant controversies and polarising rhetoric. At this stage, large segments of the voting population are essentially lost to him. He must find a strategy to win the Congressional elections and ultimately re-election on this very narrow base.

He will try to do this in part by stressing the accomplishments of his first two years – but, as noted, they are likely to be few. Republican losses in the 2017 elections in Virginia, New Jersey, and, most surprisingly, Alabama imply that such a strategy has serious limits. As with previous presidents, he will probably look to foreign policy to find quick wins that will distract and motivate his supporters.

But to do so in many areas, Trump would first have to take on his own administration, which to date has blunted his worst instincts. Given the personnel already in place, there are probably only two ways in 2018 that Trump can find expression for this political strategy.

The first is by accepting or even stoking conflict with either North Korea or Iran. North Korea remains more volatile, so conflict there is a real possibility. But the generals in Trump’s cabinet are very cautious on this issue, given the likely fallout of such a conflict. However, the Trump administration is much more unified on Iran. There is a strong consensus in the White House on the need to confront Iran and roll back Iranian gains in places such as Syria, Lebanon, Yemen, and Iraq. In 2018, we should expect there to be increasing strain on the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) – the nuclear deal with Iran championed by Trump’s predecessor, Barack Obama – and, even if the deal technically survives, greater direct confrontation between Washington and Tehran.

Trump’s second opportunity to demonstrate his impact is on trade. For all of Trump’s inconsistencies, he has remained steadfast in his view that America is getting a raw deal from the international trading system. In this area, uniquely, he has also put in place top officials that share his views. Trump will likely make dramatic moves on trade in 2018, perhaps blowing up the ongoing talks on NAFTA or increasing the use of anti-dumping or other trade sanctions to stoke a trade war with China.

Either a trade war or an actual war would be enormously disruptive worldwide, but they are perhaps Trump’s only ways out of his political dilemma at home. This means that, while his volatile rhetorical style and penchant for controversy will remain unchanged, they will be more consequential than ever in 2018.

3. Latin America: shaky normality

Latin America entered 2017 seemingly on a shaky but nevertheless encouraging path to normality. The region has in recent years demonstrated democratic resilience and a capacity for political renewal – despite a steep decline in global prices of natural resources, its chief exports.

Populists have lost power in several countries, including major ones such as Argentina and Brazil (even though, in Brazil’s case, this was due to Dilma Rousseff’s controversial impeachment). Those still in power are on the back foot. For example, Bolivian president Evo Morales is struggling to pursue his complicated path to a third consecutive presidency and Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro faces massive erosion of popular support.

Trends in 2017 signalled that, after almost two decades, the golden age of Latin America’s left was coming to an end as the region turned to more conservative leaders. Sebastián Piñera’s victory in Chile’s December 2017 presidential election has confirmed this shift. At the same time, Latin America moved further towards banishing at least two major ghosts of the past. Colombia’s government waged an uphill battle to implement its 2016 peace agreement with the country’s largest guerrilla movement, FARC, after more than 50 years of bloody conflict. And the US dispute with Cuba, a deeply polarising issue in the western hemisphere, had eased since a diplomatic thaw began in 2014.

But the region’s return to normality was wobbly from the start. The evidence from 2017 is that progress will not be easy to achieve. In the most visible crisis in the region, the Venezuelan opposition failed to translate its 2015 legislative victory into real political change. Months of protests and political mobilisation only hardened the ruling chavista party’s intent to remain in power – including by blocking an impeachment procedure, replacing parliament with the pro-government Constituent Assembly, and holding regional elections in undemocratic conditions. Colombia’s peace agreement faces outright political opposition, the threat of political and criminal violence, and implementation challenges.

Lastly, the Trump administration has both marginalised Latin America in US foreign policy and abandoned partnerships with states in the region in favour of a more unilateral and asymmetric approach. Trump has already quit the TPP, threatened to dump NAFTA, reintroduced several sanctions on Cuba, initiated several disputes with neighbouring Mexico, and openly expressed a conviction that the United States’ civilisation is superior to that of Latin America. The consequences may be dire for the political environment in the region, as Mexico’s 2018 presidential and legislative elections will likely illustrate.

Trump’s anti-immigrant rhetoric and policy may serve as another pretext for populist, nationalist, and anti-US tendencies in Latin American countries. But the region faces major challenges of its own. Politically, even if democratic regimes have prevailed over dictatorships, some remain ridden with conflict and beset with a political culture in which ruling parties feel entitled to total control. Many Latin American countries remain fraught with large-scale criminal violence and powerful criminal organisations – not to mention significant environmental, urban-development, and human-capital challenges. The region’s disappointing economic performance points to underinvestment and an overreliance on commodities, exacerbating political uncertainty.

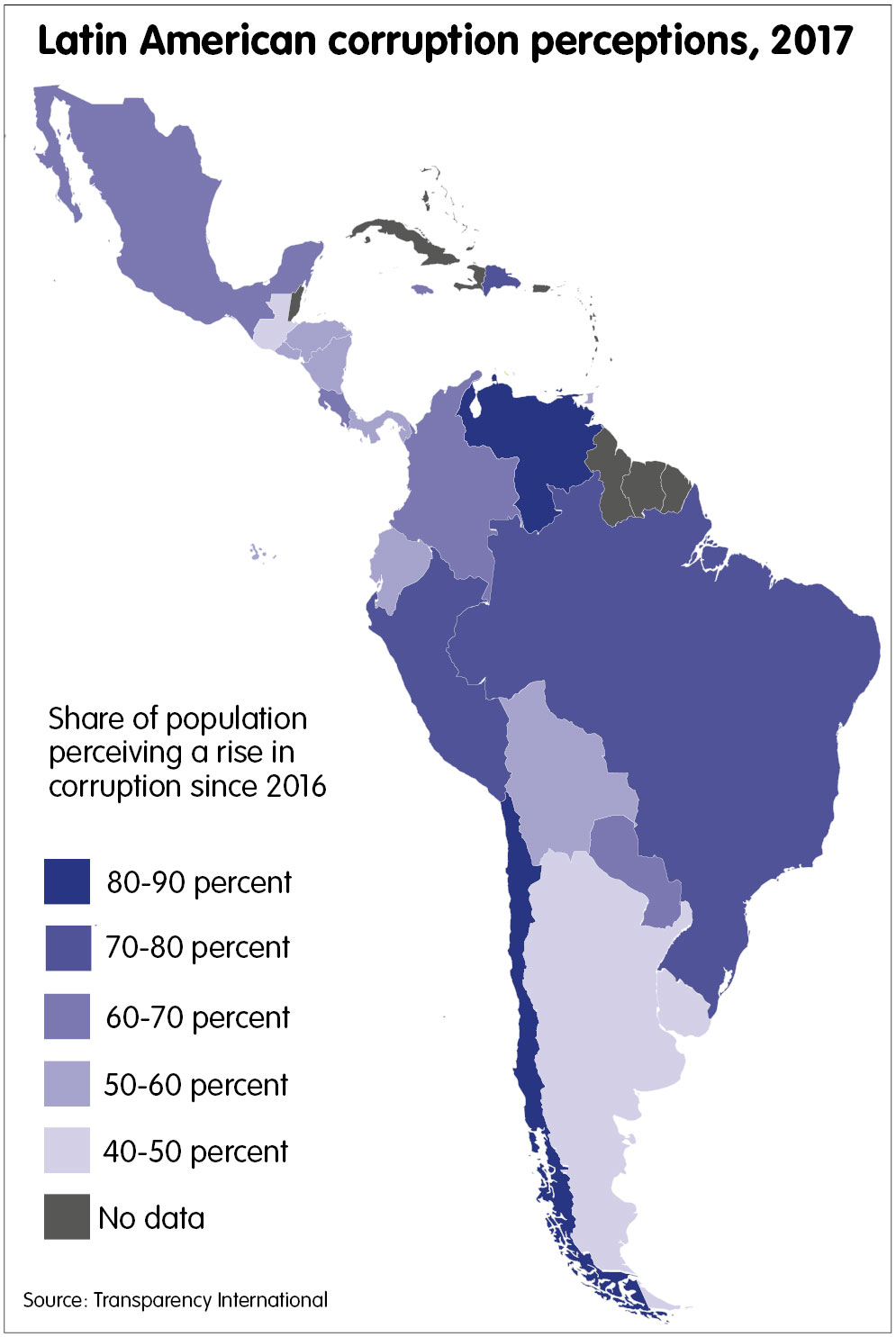

In this context, it is no surprise that Latin America is fertile ground for growing popular impatience with political elites. Against a background of massive corruption scandals – seen on a national scale (in Brazil, Mexico, and Venezuela, for example), and in the transcontinental activities of Brazilian firm Odebrecht (in Peru and Colombia, among other countries) – decreasing public tolerance for impunity, cronyism, and opportunism is becoming a key driver of Latin American politics. The consequences of this vary across countries. In Brazil, it may help rejuvenate the country’s static political system, but could also boost the chances of Jair Bolsonaro, a populist, in the presidential race. Peru may see the premature collapse of liberal technocratic president Pedro Pablo Kuczynski, given rising public indignation with his unclear links to Odebrecht and his controversial December 2017 decision to pardon the country’s former autocrat, Alberto Fujimori. The pardon could pave the way for the Fujimori family to return to power in 2018.

Prospects for 2018

In 2018, Latin America’s stability will face a series of tests, largely due to an exceptional concurrence of presidential or legislative elections in several of the region’s most important countries. Following the December 2017 run-off elections in Chile, these tests will continue in 2018 in Colombia, Mexico, Brazil, Venezuela, Honduras, Paraguay, El Salvador, Peru, and Costa Rica.

Colombia’s post-conflict reconciliation efforts are at stake in legislative and presidential elections (scheduled for March and May respectively). Rodrigo Londoño, the divisive leader of FARC, has announced that he will participate in the presidential race. His presence may boost the profile of Iván Duque Márquez, a candidate from former president Álvaro Uribe’s political camp, which questions the validity of the peace process. Even if Márquez does not win the contest, Uribe may still be able to further undermine the fragile reconciliation process.

In July 2018, Latin America’s second-largest economic power, Mexico, will hold legislative and presidential elections. Trump’s paternalistic attitude towards Mexico is already working to the advantage of Andrés Manuel López Obrador, a politically indestructible anti-establishment candidate who, like the US president, speaks in favour of protectionism and nationalism. At the time of writing, Obrador leads in opinion polls.

Brazil, the region’s largest economic power, is facing a similar threat of populism and political polarisation. The Odebrecht scandal – nicknamed Lava Jato (carwash) – has decimated Brazil’s political class, opening the door to self-proclaimed saviours and strongmen with dubious democratic credentials. For more than six months, Bolsonaro, an anti-establishment religious nationalist and former army captain, has been steadily polling in second place for the October 2018 presidential election, behind former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. Having been convicted of corruption, Lula may be excluded from the race altogether if he loses his appeal.

Venezuela is a unique case, given the country’s authoritarian drift under Maduro. Still, if opposition parties are to take power any time soon, they will have to overcome internal disputes, choose a joint presidential candidate, and mobilise their supporters once more for the presidential election likely to occur in late 2018. In the meantime, Venezuela’s political and economic exhaustion, its looming default, and apparent divisions within the army may create a window of opportunity for political change. But China’s and Russia’s unwavering support for the governing party, coupled with rising global oil prices, may once again preserve the chavista regime.

In 2018, Latin America will struggle through a dense thicket of electoral challenges. The threat is that elections may further boost instability and political polarisation in many countries. In most cases, Trump’s presidency is surely not the main source of turbulence or incertitude. However, he is certainly not helping a fragile Latin America tackle, at last, the many structural challenges that have hampered its stability and development since the fall of its cold war-era dictatorships.

4. Middle East: total chaos, with a glimmer of hope

As 2017 ends, the Middle East remains in crisis. Six years since the first protests of the optimistically named Arab Spring, the revolutions they engendered have in most cases become sources of chaos, instability, and civilian suffering. The sense that the region was unable to right itself has grown in 2017 due to ongoing conflicts in Syria, Libya, and Yemen; the crisis in relations between Qatar and other Gulf Arab states; Baghdad’s pushback against the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG); and heightened confrontation between Saudi Arabia and Iran – all problems exacerbated by uncertainty about the intentions of the new US administration. These challenges risk inhibiting efforts to stabilise areas from which ISIS has been driven, one of the year’s notable successes.

The Trump effect

As the US wields outsized influence in the Middle East, the advent of a new US administration always threatens major changes in the region. In early 2017, the broad outlines of Trump’s approach became clear. He emphasised counter-terrorism, particularly that targeting ISIS; a drive to get tough on Iran and undo the JCPOA; and an effort to rebuild partnerships with Israel and Sunni Arab states, particularly Saudi Arabia. Advancing Israeli-Palestinian peace was also touted as a signature element of Trump’s policy, but this quickly lost steam. Trump’s sudden decision in December to recognise Jerusalem as the capital of Israel told most observers that the administration had never really been serious about the peace process. The UN General Assembly voted 128-9 (with 35 abstentions) to condemn the move, while Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas responded by declaring that the US could no longer play a mediation role in peace process. All told, this means that 2018 will likely see little progress in achieving Israeli-Palestinian peace.

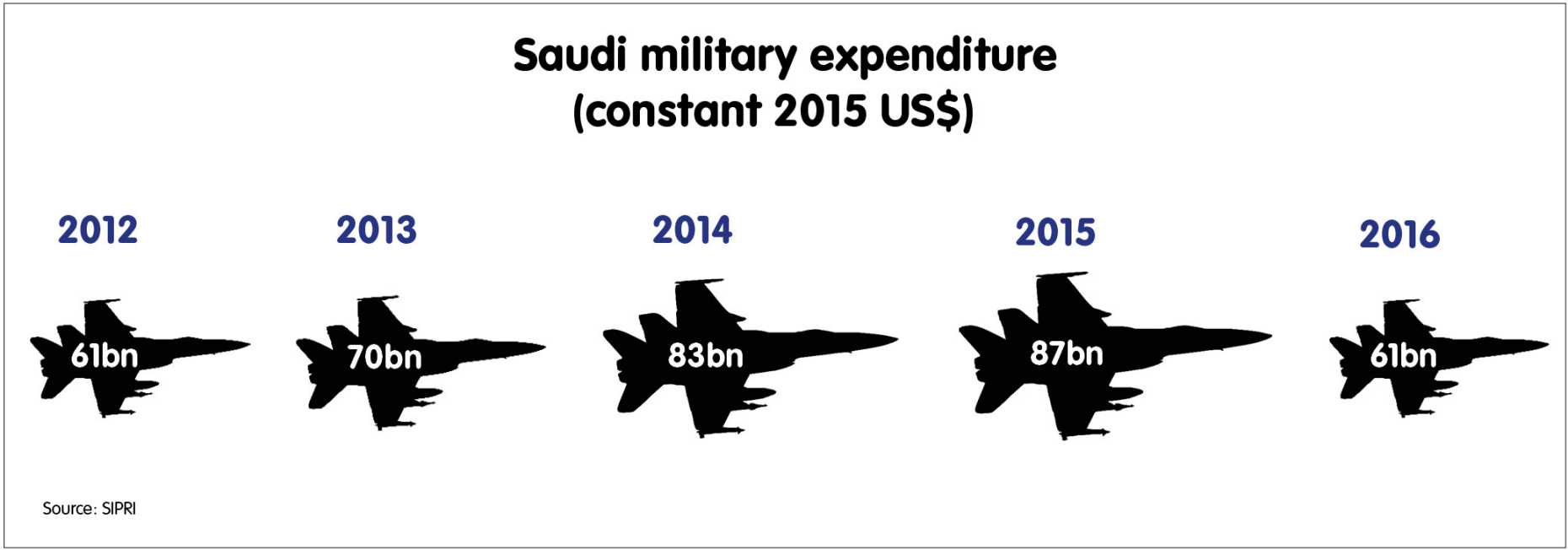

By the end of 2017, the administration’s stance on Iran had hardened, with Trump having decertified the JCPOA and made aggressive statements on Iran’s role in the region. Trump’s messaging emboldened US partners in the Middle East to try to roll back Iranian influence – if not necessarily in concert with the White House.

Saudi Arabia displayed its determination to counter the perceived Iranian threat by apparently persuading the Lebanese prime minister to announce his resignation in early November, redoubling its commitment to a costly and much-criticised military campaign against the Houthis in Yemen, and hinting that it would expand its engagement with Israel. Even the rift with Qatar, though largely a product of long-standing tension between Gulf Arab states over Qatar’s regional activities, was tinged with irritation about Doha’s flexibility towards Iran. The cumulative effect of these (sometimes manufactured) crises was to complicate efforts to de-escalate conflicts across the region and divert attention away from the long-term challenge of providing stability and effective governance.

As the ISIS military campaign winds down, what follows?

In 2017, speculation about the depth of the US commitment to post-ISIS efforts – including that on its military presence, investment in stabilisation efforts, and intentions in Syria – heightened uncertainty about the aftermath of the fighting, encouraging key regional actors to jockey for position.

The Trump administration downplayed its diplomatic role in Syria, partly because of the changing situation on the ground, which favoured Bashar Assad and his allies. Washington has tried to pacify southern Syria (and keep Iranian-backed forces away from Israel’s border), but Russia, Iran, and Turkey – each of which is pursuing its own aims – led broader efforts to de-escalate the Syrian conflict. Turkey is solidifying its hold in the north largely as insurance against further advances by the Syrian Kurds. Iran is supporting the regime’s push eastward to ensure that it has uninterrupted access to Lebanon. Russia is angling for a grand political bargain that involves just enough Syrian actors for it to claim victory and hand the task of reconstruction to Europeans – ideally, before the Russian presidential election in March 2018. None of these efforts seem likely to prompt the kind of genuine political accommodation required to restore stability in Syria.

In Iraq, elation over progress in the anti-ISIS fight was dimmed by confrontation between the KRG and the central government. The KRG handily won a popular referendum on independence from Iraq, but overall failed spectacularly in its attempt to capitalise on gains made in the fight against ISIS to rebalance relations with Baghdad. The central government – backed by Iran, Turkey, and (quietly) the US – responded with a forceful reassertion of its authority, reclaiming disputed areas held by the Kurds since 2014 and imposing strict curbs on the KRG.

The political crisis has left the KRG in political turmoil and Iraq on edge, at a moment when Iraqis and international actors invested in the counter-ISIS effort should be turning to the economic, infrastructure, and essential-service needs that follow military victory. With parliamentary elections scheduled for May 2018, the prime minister, Haider al-Abadi, will likely aim to parlay ISIS victories and rising support among Iraqi Arabs into a second term as prime minister. Regardless of who wins the election, Baghdad faces a daunting reform and reconstruction challenge – especially if it is to make good on its promise of inclusive governance, thereby mitigating the risk of resurgent extremism.

Moreover, the recapture of most ISIS-controlled areas in Iraq and Syria does not end the threat from the group. ISIS retains a network and an attack capability throughout the region, as suggested by its claims of responsibility for a bombing that killed more than 300 people on Egypt’s Sinai peninsula in November 2017. It is reportedly regrouping in Libya and gaining a foothold alongside al-Qaeda in Yemen, which has long used ungoverned spaces to organise attacks. In any case, the Middle East’s conflicts will continue in 2018 regardless of how ISIS evolves, demonstrating yet again that terrorism is only one factor in the region’s many disputes.

Meanwhile, much of north Africa remains stable but fragile. Tunisia’s quick transition to democratic governance has come under strain as figures from the old regime and corruption scandals draw increasing public attention. The government is stronger and more able to handle security threats posed by ISIS and al-Qaeda-affiliated groups, due in no small part to concerted security cooperation with the US, France, and Algeria. But its failure to respond to Tunisians’ aspirations could lead to increasing public frustration and protests in 2018.

Egypt has taken some steps towards economic reform, but its population is struggling with a falling standard of living, while armed groups based in north Sinai continue to mount large-scale attacks. Against this background, the presidential election in 2018 could indicate the extent to which President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi has lost the confidence of the country’s elites and wider population.

In Algeria, the government continues to burn through its remaining financial resources and stoke inflation. Questions swirl about whether the ailing president – confined to a wheelchair and largely hidden from public view since suffering a stroke in 2013 – will run for a fifth term in 2019 or else facilitate a long-awaited political transition. And, in Morocco, the outward-facing and modernising king so beloved in international forums continues to expand the country’s presence in African institutions and economies, even as persistent protests in the northern region of Rif threaten to trouble the government in 2018.

Regional rivalries: a recipe for deepening instability

A failure of leadership within the region is a major cause of instability. The meddling and competition for influence among regional actors – whether it be between Saudi Arabia and Iran or among Gulf Arab states – intensifies and expands the region’s worst conflicts.

In late 2017, Yemen appears to be hopelessly ensnared in the confrontation between Saudi Arabia and Iran. Prospects for de-escalating fighting, alleviating the worst humanitarian crisis in the world, and focusing on settling intra-Yemeni disputes are diminished by Saudi Arabia’s heightened sense of threat from Houthi rebels. The latter wield ballistic missiles, purportedly supplied by Tehran, along the country’s southern border. Tensions among Gulf Arab States are also polarising the region.

In late 2017, Yemen appears to be hopelessly ensnared in the confrontation between Saudi Arabia and Iran. Prospects for de-escalating fighting, alleviating the worst humanitarian crisis in the world, and focusing on settling intra-Yemeni disputes are diminished by Saudi Arabia’s heightened sense of threat from Houthi rebels. The latter wield ballistic missiles, purportedly supplied by Tehran, along the country’s southern border. Tensions among Gulf Arab States are also polarising the region.

In contrast, regional actors can open space for compromise when they step back or pull in the same direction. As 2017 ends, Egypt and Russia are tempering their continued support for General Khalifa Haftar in Libya’s east by backing UN Special Representative Ghassan Salamé’s efforts to re-establish some form of central and inclusive government. With Algeria and Tunisia having pushed in this direction for some time, the coordinated messaging that emerges from this limited convergence of interests encourages compromise among parties to the Libyan conflict. With a revised UN plan on the table, momentum may be building for an agreement among Libya’s warring parties and competing political factions. Experience suggests that the chances of success are slim but, if the sides do make progress, 2018 may begin on a relatively optimistic note.

5. Asia: confused by Trump and North Korea

In 2017, two events dominated international politics in east Asia. The first was Trump’s ascent to the US presidency. The second was North Korea’s accelerating drive towards a credible nuclear capability. The Trump administration has stepped up American diplomatic and military activity in the region. It continued freedom-of-navigation operations in the South China Sea, issued bellicose threats in response to Pyongyang’s nuclear and ballistic ventures, and directed tough talk at China – on trade, theft of technology, and North Korea. The administration also renewed the United States’ emphasis on quadrilateral cooperation with Japan, India, and Australia to counterbalance rising Chinese influence.

Washington’s allies in the region have had a broadly positive response to this increased American activism. The Japanese prime minister, Shinzo Abe, has stuck close to Trump. South Korea, despite being led by a president who favours détente with Pyongyang, feels that its strategic situation requires strong ties with the US. The Indian prime minister, Narendra Modi, has turned a deepening defence relationship with Washington into a quasi-alliance.

But the uncertainties and contradictions of Trump’s transactional approach to foreign policy are also deeply disquieting for America’s Asian allies. The Japanese and South Korean governments expended a great deal of political capital on the TPP as a hedge against China’s mercantilism and efforts to build a sphere of influence. They view Trump’s withdrawal from agreement as a surrender of long-term leadership.

Trump’s apparent desire to make concessions on trade issues with China in exchange for cooperation on North Korea also worries both countries. They see a risk of an even more brutal abandonment than the trend under the Obama administration had indicated. At the same time, some of Trump’s most radical outbursts – such as calling into question America’s “One China” policy, and promising to direct “fire and fury” at North Korea – now appear to have been merely passing fancies. The US administration includes more advocates of a strong posture in east Asia in key positions than at any time since George W Bush’s first term. But the gyrations at the top instil doubt among US allies.

North Korea’s apparent hydrogen bomb test and repeated mid- and long-range missile tests – in complete disregard of toughened UN sanctions – are the continuation of a project that began in the early 1990s. For the North Korean leadership, the nuclear programme is not merely a bargaining chip; it is crucial to a strategy for regime survival.

This strategy is nearing fruition. North Korea is just one test away – that of a long-range missile with a nuclear warhead – from acquiring a credible capability to launch a first strike against most global targets, including the US. For decades, the international community has used negotiations and sanctions to play for time while hoping for a change in North Korean policy – but time is nearly up.

A credible nuclear force presents huge problems for both the US and China. For the US, its credibility with its allies and the international non-proliferation movement is in question. For China, a visible loss of control over North Korea’s strategy will call into question its capacity to act as a security provider in east Asia.

Trends of continuity

By comparison with these two dramatic changes, there has been continuity in the other main trends in the region. President Xi Jinping has achieved greater power and ideological leadership than any Chinese leader since Mao Zedong. With Xi in charge, China now has a powerful and assertive nationalist counter-narrative with which to oppose the Western idea of market-oriented liberal democracy.

Yet China’s socialist model is meant for itself. The country’s assertive narrative is key to its global influence and to international acceptance of its ways of doing business. The narrative heralds a new era in which China mobilises experts and advanced technologies to amass national power – including, of course, military power – to exercise control over Chinese society and beyond.

China has avoided a financial crisis and maintained strong growth, even if debt – usually estimated to be around 250-300 percent of GDP – may be a financial time bomb. The country’s industrial policy and technology acquisition – along with its massive investment in artificial intelligence, robots, drones, deep-sea exploration, and aerospace – form part of an attempt to dispel the belief that only a free and open society can produce major innovations.

In relations with its neighbours, China alternately engages in bold moves and pauses in which it seeks openings for negotiation. In the South China Sea, Beijing has boldly asserted control over most of the Spratly Islands. China had only insignificant presence on the islands before it started land-reclamation work. It has constructed seven artificial islands, three airstrips, and an air defence installation there, giving the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) an edge over all other claimants. In his work report to the 19th Party Congress, Xi described construction work in the South China Sea as a major achievement of the 18th Central Committee.

With China-Japan relations in a relatively conciliatory phase, there have been fewer incidents in the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands in 2017 than in the previous year. There are signs that China seeks to manage its structural rivalry with Japan, keeping it below the level of conflict despite the countries’ immutable lack of strategic trust.

With India, China has adopted a hard line on territorial issues. But India has responded in kind. In summer 2017, the Indian military crossed the Chinese border to prevent the PLA from constructing a road in territory disputed by China and Bhutan. The gamble worked, resulting in a return to the status quo ante and showing that China is not always ready to escalate disputes.

The stand-off also highlighted the fact that China is not the only Asian country to have gained strength and resilience. In late 2017, Abe and Modi – both of whom rely on charisma and nationalist sentiment – were riding high in electoral support and popularity respectively. Both India and Japan are experiencing impressive growth. In late 2017, India’s economy is growing at an annualised rate of more than 6 percent, while Japan’s has grown for seven consecutive quarters after decades of poor performance.

China’s rise and its ambitious plans, including the Belt and Road Initiative, will once again be the most important trend in 2018. But the increasing strength of China’s neighbours means the year will continue to see competitive relationships between Asia’s major powers. This level of competition and the various geopolitical disputes in the region, particularly on the Korean peninsula, mean that 2018 presents a much greater risk of conflict than previous years.

6. Russia: planning for the presidential election

Russia maintained its dreams of greatness in world affairs throughout 2017 by pursuing an assertive foreign policy both in its immediate neighbourhood and further afield. Its kinetic wars in Ukraine and Syria rolled on without an obvious endgame in sight. Its political war against the West made headlines through efforts to influence elections in Europe. But Moscow’s main preoccupation in 2017 was its attempt to make sense of – and figure out how to deal with – the Trump administration.

The much-touted improvement in US-Russia relations did not materialise in 2017. Instead, Moscow found Trump to have been boxed in by an active Congress and an investigation into his election campaign’s alleged links with Russia. The congressional sanctions bill, the decision to provide lethal arms to Ukraine, and increases in US defence spending pointed to a more traditional, hawkish US policy on Russia. The US and Russia even engaged in a cold war-style expulsion of diplomats and closure of diplomatic facilities.

Even so, Trump continued to insist throughout 2017 that he wanted better relations with Russia. He has never criticised Putin, preserving hope in the Kremlin that the US administration will some day improve their relationship. Bilateral meetings between Trump and Putin at the G20 in Hamburg, and on the margins of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit in Vietnam, showed that Trump was willing to bend over backwards for rapprochement.

Meanwhile, Russia’s relations with Europe remained frigid. The EU maintained a unified stance on Russia and, notably, its sanctions on the country. This unity was partly buttressed by outrage over Russian meddling in domestic politics in countries such as France, Germany, the Netherlands, Spain, and the UK. But Moscow’s broad political campaign against the West – which included disinformation, support for right-wing populist parties, and cyber attacks – seemed to largely backfire. Instead of undermining European democracies, Russian meddling sensitised the European public to the threat it poses to the foundations of open societies. By the time of the German election in September 2017, Russia did not even bother mounting much of a disinformation campaign.

Russia did not give up on its ambition to bring its “near abroad” into its sphere of influence and subdue Ukraine. The war in eastern Ukraine entered its fourth year, with daily exchanges of fire and no progress on diplomatic efforts to resolve the conflict. A ray of hope appeared in September, when Putin suggested a UN peacekeeping mission for Donbas. But this ray soon flickered and died when it became clear that the initiative was little more than a diversionary ploy. By the end of 2017, fighting in Donbas had intensified; more than 10,000 people had been killed since the war began.

In 2018, Russia will continue its current foreign policy trajectory but face a more complicated international environment. However, the Kremlin’s main preoccupation in 2018 will be maintaining a stable domestic environment for the the presidential election in March and the World Cup in summer. But while football is important, the Kremlin’s priority will be ensuring the undisturbed continuation of the regime during Putin’s fourth presidential term (as well as figuring out who will succeed him). The Kremlin’s greatest fear for the election is not that people will take to the streets in protest but rather that they will stay at home and refuse to vote. A low turnout would reduce the legitimacy of Putin’s re-election as president and his nomination of a new prime minister.

Moscow will have an even more paralysed, fraught, and dysfunctional relationship with the US in 2018. The investigation into collusion between the Trump campaign and Russia will hamper the US administration’s ability to pursue any sort of coherent policy on the country. Meanwhile, increases in US military expenditure and missile defence deployments will anger Moscow, but could offer the Kremlin useful old narratives about the West for the election.

In Ukraine, Russia could move towards de-escalation and freeze the conflict – as it did a few years ago in Georgia. The current strategy of using the war to destabilise Ukraine and pressure Kyiv has proven unsuccessful and costly, especially because of the resulting sanctions on Russia. Moscow may well settle for its minimal objective of preventing Ukraine from becoming a member of NATO by freezing the conflict in perpetuity. The EU’s unity on sanctions will remain intact as it becomes clear Russia will not soon leave Donbas and even member states sceptical of the measures come to accept them as vital.

Overall, predictability and stability will be the leitmotif of Russian foreign policy in 2018. But, ever agile and unpredictable, Putin may still produce a surprise if doing so provides a tactical advantage.

7. Turkey: increasing centralisation and isolation

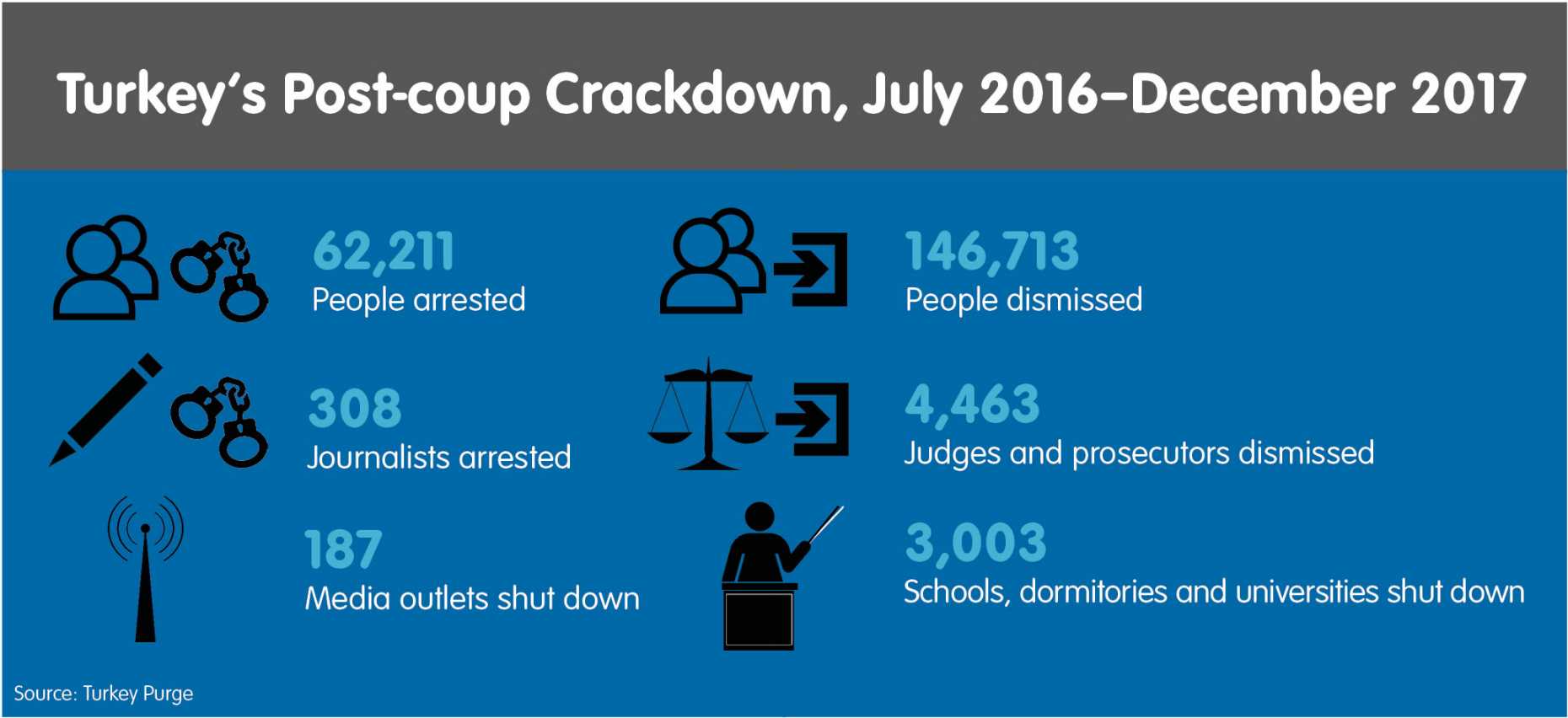

Turkey continued to slide away from democratic rule in 2017, as President Recep Tayyip Erdogan consolidated his grip on power. Erdogan’s strongman politics also manifested in Turkey’s foreign policy, alienating the country’s allies but patching up its relations with Russia.

Turkey’s relationships with both the EU and the US deteriorated throughout 2017. Europeans were troubled by Ankara’s post-coup purges and April 2017 referendum on constitutional reform, which established an executive presidency. But what most shocked European sensibilities were Erdogan’s repeated descriptions of various European leaders as Nazis, and his regime’s detention of European nationals. As Turkey’s relations with Europe worsened, a growing number of member states started to ask whether the time had come to formally suspend Turkey’s EU accession talks. Although the majority of EU member states believed that they should not rock the boat, as 2017 ended Turkey’s friends in Europe were few and far between.

There was also deepening division between Turkey and the US over Washington’s support for Syrian Kurds and its refusal to hand over Fethullah Gülen, whom Ankara blames for the failed July 2016 coup attempt. The United States’ decision to suspend visa services for Turks in response to Ankara’s detention of a US embassy employee marked a new low in the relationship. It remains to be seen whether Washington will impose sanctions on Turkey, a NATO member, for its planned purchase of S-400 air-defence systems from Russia.

There was also deepening division between Turkey and the US over Washington’s support for Syrian Kurds and its refusal to hand over Fethullah Gülen, whom Ankara blames for the failed July 2016 coup attempt. The United States’ decision to suspend visa services for Turks in response to Ankara’s detention of a US embassy employee marked a new low in the relationship. It remains to be seen whether Washington will impose sanctions on Turkey, a NATO member, for its planned purchase of S-400 air-defence systems from Russia.

In 2018, the centralisation of power in Turkey will continue. Erdogan will instrumentalise relations with Europe and the US, playing up anti-Western narratives to attract the nationalist vote as the 2019 presidential elections approach. This will further polarise Turkish society and increase tension with the West.

Will 2018 be the year that the EU breaks up with Turkey? Probably not, but marriage counselling will certainly be needed as their relationship continues its downward spiral. While the EU may not formally suspend the accession process, it is likely to impose various forms of sanctions on Ankara.

But an increasingly isolated Turkey, coupled with a sharp decline in the country’s economic growth, could restrain Erdogan’s worst instincts, especially in the lead-up to the presidential elections. The IMF projects that Turkey’s economy will grow by 3.5 percent in 2018, down from 5.1 percent in 2017. Erdogan’s popularity has always rested on delivering economic performance. If the economy takes a nose-dive in 2018, his resulting electoral weakness will force him to repair relations with Turkey’s largest economic partners in the West.

Reversing trends in 2018

The key to understanding the future lies in not just identifying the most important trends but also assessing how purposeful behaviour by key actors, and even unplanned events, might reverse these trends. In this section, we identify the key opportunities for Europeans to address some of the trends described above. This is not a prediction; it is an illustration of the ways in which these trends in no sense lead to inevitable outcomes. The section emphasises the fact that trends can always be reversed or have surprising consequences.

The retreat of the populist wave?

2018 could see the crest of the populist wave that has roiled Western politics for the last few years. In 2017, the picture has been mixed. Populists gained vote share across Europe and Alternative für Deutschland entered the German parliament for the first time, but populists failed to attain power in the Netherlands or France, and, indeed, the French public elected a decidedly mainstream leader as president.

Three key issues in 2018 will help determine which possible future holds sway. The first is whether the new German government works with Macron to relaunch the European project and thereby provide an alternative narrative to that of nationalist populism. The second is whether the Italian elections deal a defeat to the Five Star Movement, demonstrating yet again that populists have limited appeal in key European countries. The final issue is whether the United Kingdom descends towards a chaotic Brexit that would damage its economy, showing that populist policies offer no panacea for the problems of globalisation and anaemic income growth.

Technology

Europe has an opportunity in 2018 to reverse the trend of it falling behind in digital technologies. It has the capacity to commit to the unfolding technological competition over quantum computing, artificial intelligence, and robotics. The alternative is to fall even further behind, with China and America shaping technological standards and norms of use. European leaders could use the European Commission’s €1 billion quantum project and Macron’s proposal to create a European DARPA as an entry point into a much broader promotion of technological innovation on the continent. This is the area in which economic growth, security, and the preservation of democracy will take shape in the future.

The authoritarian option

The likelihood that Trump will have difficult relations with Putin, Erdogan, and Xi provides an opportunity for Europe to reverse the trend of increasing European irrelevance, by both cooperating with and pressuring the White House.

Europeans can work with Beijing to protect international institutions such as the Paris Agreement on climate change when necessary and possible. But they should have no illusions: they will also have to adopt a more realistic and political (rather than purely economic) approach to dealing with China, whose reasons for working with Europe are hardly idealistic.

No comments:

Post a Comment