By Jack Thompson for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

In this Strategic Trends 2017 chapter, Jack Thompson argues that the election of Donald Trump, and the emergence of his America First credo, promises a world where the US will not pursue an internationalist foreign policy. As a result, Europe would do well to begin planning for a future in which the US is more skeptical of alliances and trade agreements and less willing to assume a leadership role in resolving international problems.

In this Strategic Trends 2017 chapter, Jack Thompson argues that the election of Donald Trump, and the emergence of his America First credo, promises a world where the US will not pursue an internationalist foreign policy. As a result, Europe would do well to begin planning for a future in which the US is more skeptical of alliances and trade agreements and less willing to assume a leadership role in resolving international problems.

This article was originally published in Strategic Trends 2017 by the Center for Security Studies on 22 March 2017.

Support in the United States for the liberal world order is under threat from a combination of profound economic, cultural, and political changes. The election of Donald Trump, and the emergence of his America First credo, underscores the fact that the world can no longer depend upon the US to pursue an internationalist foreign policy. Europe, in particular, would do well to begin planning for a future in which the US is more skeptical of alliances and trade agreements and less willing to provide leadership in addressing international challenges.

Introduction

For decades, Americans benefited greatly from the liberal international order that the United States has promoted ever since the end of World War Two. This includes formal security alliances with Europe, in the form of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, and with nations such as Australia, Japan, and South Korea. It is also based upon a set of financial, monetary, and trade institutions that have encouraged international trade, placed the US dollar at the heart of the international economy – first as part of the Bretton Woods System and after 1971 as the world’s foremost reserve currency – and made New York City the world’s leading financial center. Key financial and monetary institutions, such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, are located in Washington DC. In addition, the liberal order relies upon respect for a shared set of values. These include administering democratic elections, protecting the rights of religious and ethnic minorities, a commitment to human rights, and upholding the rule of law.

Maintaining this web of alliances, economic structures, and values has not come without challenges. These included the collapse of the Bretton Woods System in 1971 and longstanding imbalances in military spending between the US and its allies. Overall, however, it has reinforced and institutionalized the role of the US as an economic and military superpower. For decades, it also contributed to a steadily improving quality of life for most Americans and optimism about the future. Not surprisingly, this arrangement faced little opposition for many years and a bipartisan consensus coalesced around internationalism as the cornerstone of US foreign policy. Seminal advice from leaders in the early 19th century, such as Thomas Jefferson and John Quincy Adams, about avoiding “entangling alliances” and not going abroad “in search of monsters to destroy”, no longer seemed relevant.

Recently however, and especially since the Great Recession of 2008, it has become clear that many Americans no longer see the liberal international order as a beneficial arrangement. This means that the election of Donald Trump, and the embrace by many of his “America First” credo, is a symptom, not the cause, of an underlying evolution in the political fundamentals – namely, that US foreign policy is undergoing its most dramatic transformation since the onset of the Cold War. Three interrelated types of problems that, it is clear with hindsight, have been gestating for years are driving this: globalization fatigue and other economic crises; increasing multiculturalism and a corresponding backlash among cultural conservatives; and political dysfunction.

The upshot is that internationalism is no longer the default American worldview. This should worry the rest of the world. Europe, in particular, should think carefully about its longstanding partnership with the US, especially when it comes to European goals and values, trade, security cooperation, and the rise of right-wing populism.

Globalization Fatigue and Interlinked Economic Crises

Recent headlines would seem to indicate that the US economy is relatively strong. After contracting by 2.8 per cent in the wake of the global economic crisis, gross domestic product grew steadily between 2010 and 2015 and appears to have been at least as strong in 2016. The unemployment rate, after reaching a peak of 10 per cent in October of 2010 – which is very high by US standards – has been steadily dropping. It reached a low of 4.6 per cent in November 2016, which constitutes full employment in the US context. Perhaps most impressively, household income rose by more than 5 per cent in 2015, breaking a pattern of years of stagnation.1

However, a closer look indicates that important sectors of the economy, and many parts of the country, have been in crisis for some time. The overarching problem is often characterized as globalization fatigue (a term which cannot convey the massive transformation that has taken place for many Americans): discontent with the upheavals that usually accompany deeper integration with the global economy, such as loosened capital controls, lowered barriers to trade, and reducing obstacles to foreign direct investment.

The problem Americans most frequently attribute to globalization is the loss of manufacturing jobs to lower-income countries (though many economists consider technology to have had a much larger effect in this respect). The conventional argument in favor of free trade holds that, although some sectors of the economy will see job losses due to competition from cheaper imports, workers in these industries will find employment in more efficient areas and the overall economy will benefit. However, as the authors of a recent paper on trade with China argue, the reality has been more complicated. Job losses in industries exposed to import competition have been significant, as expected, but new jobs for these workers in other industries have mostly not emerged. To make matters worse, areas of the country where the worst-affected industries are located, such as parts of the Midwest and Southeast, have also experienced rising unemployment rates overall, as the departure of the manufacturing base undermines the rest of the local economy (and as Americans, once famously peripatetic, become less willing and/or able to relocate). This has literally become a matter of life and death. Regions disproportionately exposed to trade liberalization have higher rates of mortality, due to suicide and other causes of death that have been linked to reduced income and employment. This has been particularly true for working-class white Americans.2

Those working in traditional manufacturing jobs are not the only ones to have suffered in recent years. Young Americans also face significant economic challenges. The extent to which these can be directly attributed to globalization is debatable, but the end result – pervasive resentment of the status quo – is not. The official unemployment rate for those under the age of 25 was 11.5 per cent in July 2016. However, that number understates the problem, perhaps by a significant margin. A report by the Economic Policy Institute in 2015 found that the unemployment rate for recent high school graduates is almost 20 per cent. The underemployment rate – which tracks part-time work undertaken by those who would prefer full-time jobs – is higher still: nearly 15 per cent for college graduates and 37 per cent for those with only a high school diploma. These numbers are even worse for African-Americans and Hispanics.3

Even for those that manage to enter university, formidable challenges await that are further reducing social mobility and increasing income inequality. The cost of attending university in the US has risen dramatically over the last few decades, at a rate far higher than inflation, from an average of just under US$11’000 in 1983-4, for four-year institutions, to more than US$36’000 in 2013-4. This has made higher education much less affordable for the middle and working classes and, not surprisingly, led to an explosion in student debt levels. As of September 2016, borrowers no longer in school owed almost US$1.4 trillion in loans. Many of these former students – about one quarter – are behind in their loan payments or are in default. This has prompted warnings from some observers of a student debt “bubble” reminiscent of the housing bubble prior to the 2008 financial crisis.4

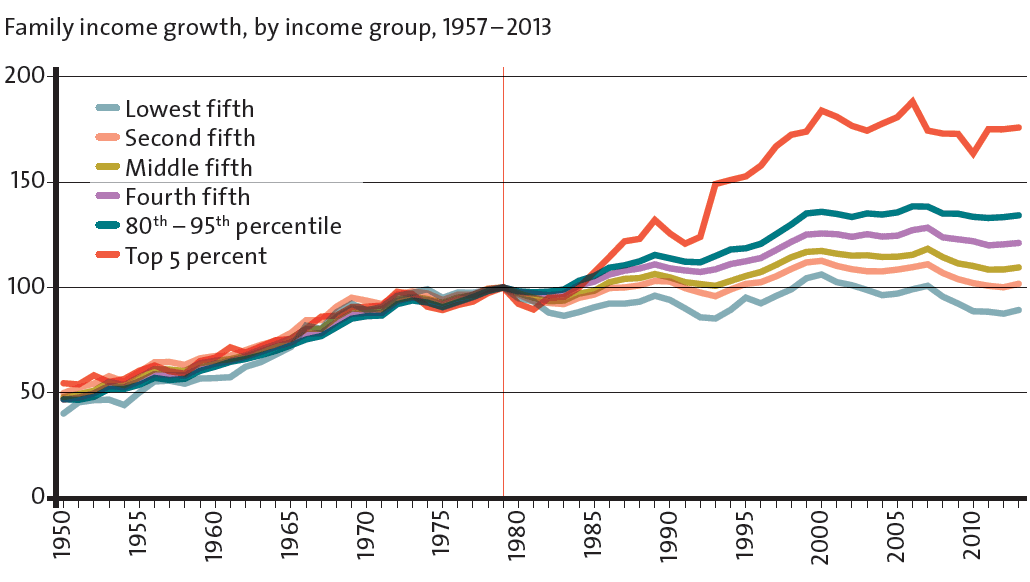

At the same time that many sectors of the traditional manufacturing economy contract, and young Americans endure a prolonged economic crisis, other concerns have emerged. One worrisome trend is the disconnect between labor force productivity and income. The share of economic output that workers collect in wages is at the lowest level on record. In fact, since the early 1970s, even as the productivity of the workforce has increased by more than 70 per cent, pay levels have been stagnant, rising only 8.7 per cent over a span of three decades. A second problem is rapidly growing inequality, to perhaps the highest level in US history. Since 1979, the wages of the top 1 per cent of earners have increased 138 per cent, whereas the income of the bottom 90 per cent has only risen 15 per cent. Hence, by 2013 families in the top ten per cent controlled more than 75 per cent of all family wealth.5

The Rich Getting Richer

Source: Economic Policy Institute

It is true that many communities in the US have benefited considerably from adapting to the globalized economy. And a plausible argument can be made that overall the US is in a stronger position because of its willingness to embrace the transformation induced by globalization. But the process has taken a profound toll on many parts of the country.

This is not only a matter of economic concern; it is also clear that globalization has become difficult to sustain politically. Even if we set aside as a fluke the election of Donald Trump – who ran for president on a staunch anti-globalization platform – his worldview is increasingly representative of the Grand Old Party (GOP). A majority of Republican voters now consider global economic ties to be, on the whole, bad for the US. What is more, although Democrats still consider engagement with the global economy to be worthwhile (albeit by a narrow margin), a majority of Americans now consider it to be bad for employment and wage levels.6

Given the longstanding commitment to internationalism among elites in both parties, it was always likely that those most concerned about the effects of globalization would become disenchanted with the status quo. In addition, in a country where many view immigration and multiculturalism as being closely linked to globalization, it was inevitable that cultural resentment would constitute part of the revolt against elites.

Multiculturalism, Immigration, and the Conservative Backlash

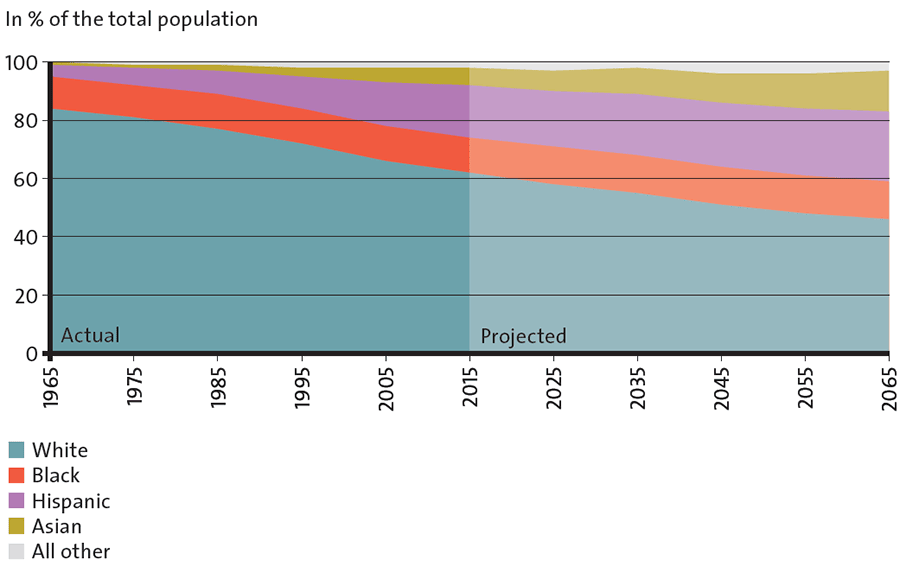

The US is becoming more diverse. Sometimes referred to as the “browning of America,” this trend is driven by two factors. One is a relatively high rate of immigration – 14 per cent of the population is foreign-born – especially from Latin America and Asia. The other is a lower fertility rate among non-Hispanic whites than is the case among most minority groups. For the first time in history, in 2015, a majority of children under one year of age were racial or ethnic minorities.7

Many observers – especially those in the media and academic elite – have celebrated this fact, or at least portrayed it as a normal and mostly advantageous consequence of living in a globalized era. There is much to be said for this viewpoint: the newcomers prevent population loss – a critical problem facing some advanced economies, such as Germany and Japan – and bring new ideas, skills, and customs with them when they arrive. However, the arrival of large numbers of immigrants also dilutes the primacy of the White Anglo-Saxon Protestant tradition that has dominated American culture since the founding of the nation. There is considerable unease about this among culturally conservative white Americans, many of whom have – especially in the years since the election of the nation’s first non-white president, Barack Obama – fiercely criticized the notion that immigration, diversity, and multiculturalism are good for the country.

The Changing Demographics of America, 1965–2065

Source: Pew Research Center

This perspective comprises several elements. One is an urgent sense that the country is changing rapidly, and for the worse. Long before Donald Trump crafted a successful presidential campaign around the theme of making America great again, prominent voices have been warning that, absent dramatic changes, the nation faces an unpleasant future. Patrick Buchanan, the former speechwriter for Richard Nixon, ran for president on this platform in the 1990s and has published books with titles such as Suicide of a Superpower: Will America Survive to 2025? In Who Are We? The Challenges to America’s National Identity Samuel Huntington, the eminent political scientist, argued that the unique American sense of identity – based upon the Anglo-Protestant “principles of liberty, equality, individualism, representative government, and private property” – was being undermined, perhaps fatally, by economic globalization and immigration from Latin America. A focus group conducted in 2013 concluded that self-identified Tea Party (essentially anti-establishment conservative) voters “want to return to a time when they believe government was small, people lived largely free of the government, and Americans took responsibility for themselves.”8

Closely related to this notion – that the country has lost touch with a more virtuous past – is the belief that minorities, especially African-Americans and Hispanics, are less likely to embrace traditional values. Instead of working hard like other Americans, goes the argument, they are more likely to rely on the government for support. A member of the Oklahoma state legislature, for instance, argued during a debate about affirmative action in 2011, “I’ve taught school, and I saw a lot of people of color who didn’t study hard because they said the government would take care of them.” One study found that Tea Party adherents placed considerable emphasis on their perception of “workers” and “people who don’t work.” Included in the second category were unauthorized immigrants “who may try to freeload at the expense of hardworking American taxpayers.”9

Indeed, a key finding of scholars who have examined white resentment is that, in spite of the fact that conservative intellectuals champion limited government, there is actually little opposition to federally funded social insurance, among the rank and file, as such. Instead, there is more selective anger that those who have worked hard and thereby earned such assistance are being crowded out by minorities who, it is believed, do not deserve it. As one man in Wisconsin told a journalist, “Free services for illegal immigrants? I had to fight six months to get food stamps after my back injury...I’m from here, my whole life…And this is the way we get treated.” Similarly, studies demonstrate that whites increasingly view gains for African-Americans as coming at their expense and view reverse racism as a more significant problem than traditional racism.10

Working-class whites are at the heart of the conservative cultural backlash. This group is confronted by multiple crises. In many parts of the country, it has been devastated by the loss of traditional manufacturing jobs and stagnant wage levels. In numerical terms, the white working class is shrinking as a per centage of the electorate, from nearly three quarters of eligible voters in the mid-1970s to less than half today. They are also less healthy than the rest of the population. One study found that middle-aged white men and women suffered an increase in mortality rates in recent years that was not seen in other ethnic groups or in other countries. The biggest increases were seen among whites with lower education levels. Not surprisingly, scholars have documented a strong sense of unhappiness and pessimism among suburban and rural uneducated whites that is not found among minority groups in similar circumstances.11

The white working class is all too aware of its diminished status, as one scholar notes, and he argues that recognition of this – in other words, awareness of the fact that they no longer occupy a central and influential role in American life – is a key factor in their radicalization. This process has played a crucial role in the emergence (or re-emergence) of extremist political behavior in recent years. It has taken several forms. One is a strong correlation between white working-class disaffection and the renewed importance of outright racism – as opposed to more subtle coded language – in shaping political behavior (the election of Barack Obama also played a central role in this process).12

Another worrying manifestation of radical political behavior is renewed enthusiasm among white nationalists. This includes the emergence of the so-called alternative right, or alt-right, a loose grouping of men that, mostly online, organizes and promotes a variety of fringe ideas. Traditional white supremacists have also been reinvigorated and view Donald Trump as the first president in the modern era who is sympathetic to some of their objectives.

Equally disquieting is the increase in illiberal political views. These numbers are particularly high among young people – only 30 per cent consider it “essential” to live in a democracy – and among supporters of Trump, just 40 per cent of whom retain faith in the US system.13

To be sure, the growing lack of trust in Washington DC cannot be attributed solely to the spread of illiberal ideas. Many Americans who embrace democratic norms are nevertheless deeply pessimistic about their system of government. That is because, in recent years, it has become increasingly dysfunctional.

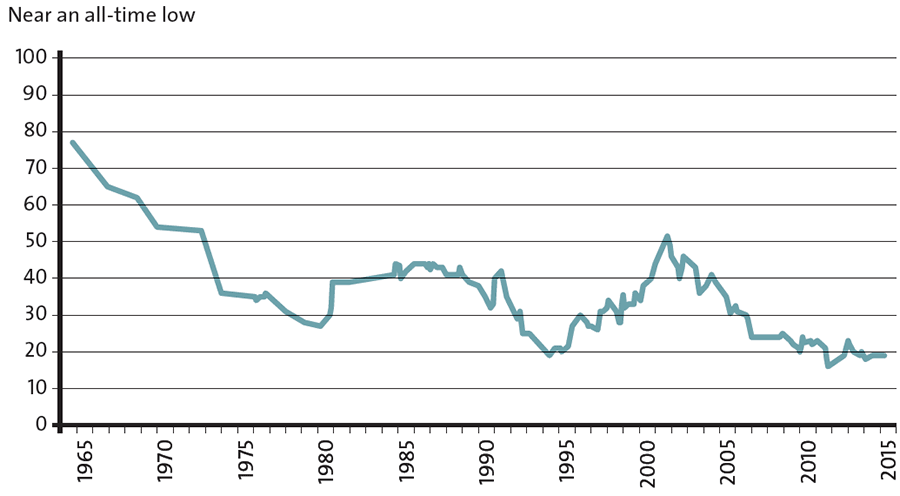

Political Dysfunction

There is little common ground in US politics these days, but voters across the spectrum agree that the government is broken. For the second year in a row, according to Gallup, respondents named the government as the biggest challenge facing the country. This result reflects a number of concerns. Congressional job approval, for example, stands somewhere in the low to mid-teens and has rarely reached 50 per cent over the last 40 years. In addition, according to a recent survey by the Associated Press-GfK, a large majority believe that the federal government mainly benefits corporations, lobbyists, and other special interests. Not surprisingly, nearly three in four respondents believe that the country is heading in the wrong direction.14 A growing body of scholarship also lends credence to the notion that the government is dysfunctional.

American Trust in Government

Source: Pew Research Center

Why is this? And why have politicians failed to fix a set of problems that have been obvious for years? One explanation is that these shortcomings are an inevitable result of the design of the US Constitution. Some scholars, for instance, note that presidential systems have, on the whole, been less stable than parliamentary systems. Holding separate elections for the executive and legislative branches, they contend, is inherently problematic because it inevitably leads to a fight for power. In fact, the US struggles across the board when it comes to running free and fair elections. Experts found that out of 22 industrialized democracies, the US ranked last in terms of electoral integrity. The office of the presidency, in particular, is potentially dangerous. It is an enormously powerful position – if not in the original conception of the framers of the Constitution, then certainly in its modern, “imperial” incarnation – especially when it comes to foreign policy. And because of the dissatisfaction that most voters express when it comes to the government, there is a temptation for candidates to craft personalized – even demagogic – platforms in which they promise to radically transform Washington DC. It has also been suggested that a system conceptualized in the late 18th century for a geopolitically marginal nation with a few million inhabitants, and which limited suffrage to a fraction of the populace, cannot possibly cope with the challenges of governing a democratic superpower with a globalized economy and a population of more than 320 million.15

Even those that consider the Constitution to be of sound design tend to agree that the US system of government no longer functions as it should. Conservative intellectuals, for instance, believe that the federal government has grown too large to be effective or democratically accountable and, as a result, is rife with rent-seeking behavior by special interests. In addition, they contend, the president and the courts have usurped powers that the framers of the Constitution intended to be exercised by Congress.16

Though few outside of the movement would agree with the conservative prescription for this problem – to shrink dramatically the size of the federal government – the view that Washington DC is more responsive to elites than to ordinary people is widespread. One study found, for instance, that business groups and their political allies have far more influence on public policy than do voters or civic groups. Francis Fukyama, the political scientist, has characterized this as part of a broader process of “political decay.” He argues that functions that, for much of the post-New Deal era, were the preserve of a skilled bureaucracy (and still are in other modern democracies) are now overseen by Congress and the courts, much as they were in the 19th century. The quality of government has steadily declined in recent decades, he contends, as the bureaucracy becomes less meritocratic, policymaking gets captured by special interests, and the enforcement of laws becomes increasingly litigious and less predictable.17

Another explanation for political dysfunction is that one of the two main parties has been radicalized to such an extent that it is sabotaging the system. For close observers of politics in the US, it has been clear for some time that the Republican Party – in spite of the fact that it now controls the White House, both chambers of Congress, and a majority of governments at the state level – is in crisis. Most of the increase in political polarization in recent years is the result of the GOP moving rightward, transforming from a center-right party into one that is very conservative. It is increasingly disdainful of expertise and evidence and is resistant to information that does not originate from within the movement (a phenomenon that has been called “epistemic closure”). The result is that, as two political scientists put it, conservatives today “show less interest in policy details or execution than they do in upholding the symbolic ideals of limited government, American nationalism and cultural traditionalism.”18

One consequence of this ideology is that, over the past two decades, Republicans have shown a striking disregard for the norms that are essential for the proper functioning of the federal government. Beginning with Newt Gingrich’s tenure as Speaker of the House of Representatives in the 1990s, they have frequently threatened to shut down the government, to instigate a default on the government’s debt, or to eliminate vital government programs in order to extract concessions from Democrats. The same is true for their growing inclination to block judicial and executive branch nominees by Democratic presidents, regardless of qualifications.19

This radicalization is intensified by unceasing pressure from the grassroots of the GOP, which is deeply suspicious of party elites. One reason for this distrust is the belief among conservative voters that their principal concerns – immigration, the negative effects of globalization, and a generalized fear that the country is changing for the worse – have been ignored by their elected representatives, who have prioritized tax cuts for the wealthy and favors for their friends and colleagues in government and corporate America. The massive bailout packages that the financial industry and General Motors received during the recession heightened this sense of betrayal. Trump’s presidential campaign platform was astutely designed to take advantage of such concerns.

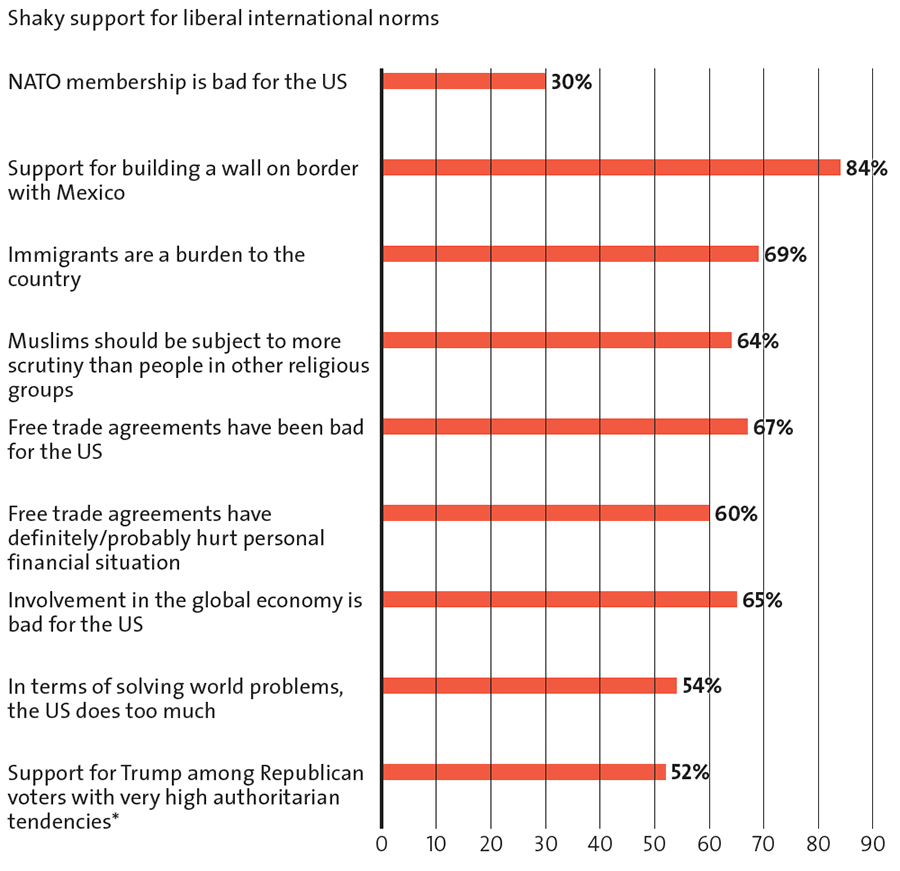

Perhaps most troubling, in recent years, is the embrace of non-democratic norms in the GOP. Some scholars have found, for instance, that the single most reliable factor in predicting support for Donald Trump in 2016 was the degree to which voters held views that correlate with authoritarianism (which can be defined as a desire for order and a fear of outsiders). It is tempting to dismiss the party’s nomination of, and strong support in the general election for, Trump – 90 per cent of Republicans voted for him – as an aberration. But his worldview – with his admiration for dictators, his penchant for conspiracy theories, his suggestion that he might not respect the election results if he lost, and his threat to put Hillary Clinton in “jail” – actually dovetails nicely with conservative political culture. After all this is a party that has, in recent years, passed laws designed to depress the turnout of minority voters. Nearly three quarters of its supporters still doubt that Barack Obama is a US citizen.20

That so many Republicans are susceptible to such conspiracy theories underscores another set of problems: the fragmentation and polarization of the media landscape. With the onset of the information age and the rise of social media, the choice of news providers is larger than ever. In contrast to most of the post-World War Two era, when a relatively small number of newspapers and television stations furnished the vast majority of daily news, voters today can consult (often partisan) sources of information that conform most closely to their preconceptions.

This has a number of consequences for political life. The new, more diverse media landscape paradoxically intensifies polarization (and hinders pluralism) as voters, especially those that are most engaged with the political process, become less open to information that contradicts their views. It also decreases the influence of traditional authority figures in the media – such as The New York Times or the nightly news broadcasts on the major networks – and those that have customarily used the media to communicate with potential voters, such as public officials.21

This means that it is increasingly difficult for accurate information to reach the public, let alone for people to be persuaded. As we have seen over the last eight years in particular, whether it relates to Barack Obama’s citizenship or global warming, false information can be attractive to many people if it reinforces their worldview. This is one reason that fake news has become such a problem.

In fact, fake news is now an international business. In the Macedonian town of Veles, for instance, locals developed a thriving industry of websites aimed mostly at Trump voters. It is also a national security problem. Russia, which has developed a sophisticated apparatus for disseminating propaganda abroad, takes advantage of the American appetite for fake news, according to intelligence officials, and skillfully used the US media in its campaign to ensure the election of its preferred candidate, Trump.

The Future of Transatlantic Relations

The resurgence of Russia, and its willingness to manipulate Western elections, highlights the indispensability of a robust US-European relationship. However the bond, as it has existed since the end of World War Two, is at risk. Perhaps most alarming is the fact that public support for the transatlantic project is on the wane. There is profound anger at elites in both parties and this has affected, in particular, the traditional autonomy of foreign policy insiders and officials. This would have been true even if Hillary Clinton had won the election. Clinton, for instance, felt compelled to withdraw her support for the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) agreement when she decided to run for president. There is no question, though, that Trump’s victory has intensified the challenge facing internationalists on both sides of the Atlantic.

At the systemic level, the question from the European standpoint is: to what degree will the US continue to be a viable partner for pursuing strategic goals and upholding values? Many of the initial indications from the Trump administration are not promising in this respect. Trump’s indifference to democratic norms – and the willingness of many Americans to overlook this disturbing trait – is unsettling for most (with the obvious exception of the European populist and illiberal right). His characterization of the European Union as little more than an instrument that Germany uses against the US in the competition for exports indicates that he has little sympathy for, or understanding of, the seminal role the European project has played in promoting peace and stability. His dismissal of the United Nations as “just a club for people to get together, talk and have a good time,” his choice of Governor Nikki Haley – who has no international experience – for ambassador to the UN, and the overwhelming support among Republicans in Congress for cutting funding to the body do not bode well for his administration’s view of the importance of international law and multilateral institutions.

Moving from the systemic to the specific, further liberalization of trade between the US and Europe will likely cease for the foreseeable future. Given Trump’s strong opposition to such deals, the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) negotiations, which were already facing potentially fatal opposition on both sides, are already effectively over. This dovetails with the president’s withdrawal from the TPP agreement, his promise to crack down on what he has called unfair trading practices and currency manipulation by China, and to renegotiate the North American Free Trade Agreement.

Taken as a whole Trump’s trade agenda could destabilize the international economic system. It could also have profound strategic implications. The Obama administration viewed TTIP and TPP as companion agreements that were intended to increase trade and prosperity and to promote stability and the development of a rules-based international system, especially in East Asia. China, which was not included in TPP, has moved quickly to replace it by suggesting a Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific. Success in this endeavor would boost Beijing’s goal of regional leadership and be a significant blow to the US

The magnitude of these setbacks in East Asia is compounded by the fact that Trump presents transatlantic security cooperation with its gravest challenge since the inception of NATO. He is the first president to publicly voice skepticism about the value of the alliance. It should be noted that more than three-quarters of Americans still believe that it is beneficial and Europe continues to enjoy a positive image in the US. However, the share of voters (37 per cent) who think that NATO benefits other countries more is almost as large as those (41 per cent) that believe it is equally important to the US. Also, a large minority of Trump’s supporters are skeptical about NATO.22

What these numbers suggest is that, although US-European security cooperation still enjoys broad support, it is no longer a political liability, as it would have surely been even a decade ago, to suggest that the US should reconsider its participation in NATO. Trump did not create this skepticism but he has used it more effectively than any previous politician. Although presidential rhetoric rarely leads to dramatic shifts in public opinion, it can set the agenda for public discussion, especially among voters in the same party. Also, when it comes to foreign policy many voters are relatively unengaged with the issues and frequently follow the cues of party elites.23

In other words, even though many Republican officials disagree with him, Trump has used his rise to power to inculcate skepticism of NATO into the mainstream of Republican foreign policy thought. In this light, it is worth recalling Lord Ismay’s witticism about NATO being designed “to keep the Russians out, the Americans in, and the Germans down”. Without the enthusiastic participation of the US, which spends more than twice as much on defense as all other member countries combined, the alliance would quickly collapse and the foundation for European security would disappear.

Trump Voters During Presidential Primaries

* Scholars have found that authoritarianism was the single best predictor of support for Trump during the Republican primaries. Sources: Pew Research Center; Vox

Ismay’s bon mot has bearing on another issue: relations with Moscow. The president’s ambivalence about NATO, when seen against the backdrop of his statements about Russia, suggests that there could be a significant shift in the US-European-Russian relationship, especially as it relates to the alliance’s eastern flank. It is too early to predict with any confidence how he would react to a conflict and it is possible that, sooner or later, Trump and Vladimir Putin will clash as a result of their nationalistic agendas. Nonetheless, there is ample reason for concern. The nature of Trump’s comments – he has praised President Putin and called for closer ties with Moscow – indicate that, at a minimum, he is untroubled by the nature of Russian foreign policy. Furthermore, Trump is unenthusiastic about restraining Russian revanchism in Eastern Europe. His team – which was otherwise unengaged with the drafting process – intervened to ensure the removal of a line in the Republican Party’s platform that called for providing lethal defensive weapons to Ukraine. He is also unwilling to commit to defending the Baltic nations in the event of an attack. This suggests that, at a minimum, the President cares more about the relationship with Moscow than he does about allies in Eastern Europe. It is no wonder that many observers have begun to speculate about a second Yalta, wherein Trump and Putin would agree to carve out spheres of influence at the expense of other nations.

This unsettling relationship, between the autocrat Putin and the democratically-elected but illiberally-inclined Trump, underscores another reason why European policymakers should take stock of their ties to the US. The election of a radical right-wing populist to the presidency has provided an enormous boost of confidence to parallel movements in Europe. Nigel Farage campaigned for Trump (who then brazenly suggested that the former UKIP leader be appointed as ambassador to the US), Marine Le Pen has been spotted at Trump Tower, and Geert Wilders predicted that Trump’s victory foreshadowed similar outcomes in Europe. But the links go beyond mere favor-trading and moral support. Those close to Steve Bannon, Trump’s chief strategist and former executive chairman of the far-right website Breitbart News, suggest that his praise of European nationalists is more than mere rhetoric: he is looking for ways to cooperate with them. In other words, in spite of the differences between Trumpism and the agendas of these groups, there is now a loose but identifiable transatlantic coalition of right-wing populist parties that is eager to collaborate and exchange ideas that are hostile to liberal internationalism.

The Need for a More Assertive Europe

Europe should not give up on the US. A majority of Americans still consider the transatlantic relationship to be of value and most members of the economic and political elite believe it is imperative that the US continue to uphold the liberal international order. These facts will not change anytime soon. What is more, there is a good chance that Trump’s successor will be a more desirable interlocutor.

However, even if Trump is not re-elected in 2020 and is replaced by a committed internationalist, the nature of US-European relations has already been permanently altered. Too much has changed for the US to fully return to its previous role of unflagging leader of the free world. The allure of the nation’s approach to foreign policy in the 19th century, when Americans believed that the best way to safeguard liberty and prosperity at home was to avoid involvement in problems abroad, is greater than at any point since 1945.

In concrete terms, Europe should expect little from the new administration. Sympathy for the many challenges facing Europe will be in short supply. When it comes to collaborating to address the problems in Europe’s backyard, à la the joint intervention in Libya in 2011, the Trump administration is unlikely to be as agreeable as its predecessors. For instance, it would be surprising if the president were willing to cooperate vis-à-vis the conflict in the Ukraine. Indeed, though he has sent mixed signals on this issue, there is reason to believe that he will lift US sanctions on Russia.

Instead of seeking partnership with Europe, we can expect the US to emphasize unilateral action – with the fight against ISIS as a chief priority – and relationships with other significant powers such as Russia and China. (The potential exceptions in this context are collaboration with Moscow in combating ISIS and perhaps employing the United Kingdom as a very junior partner.) Also, the president’s team and Republicans in Congress have little appetite for cooperating with international institutions and organizations, with the UN in particular emerging as a target for criticism.

In sum, if it cares about the maintenance of the liberal international order Europe will have to carry more of the burden in the future. If one looks for silver linings in the current state of affairs, the genesis of a more vigorous European foreign policy would certainly qualify.

Notes

1 World Bank, GDP Growth (annual %), United States; Bureau of Economic Analysis, National Income and Product Accounts: Gross Domestic Product: Fourth Quarter and Annual 2016 (Second Estimate), 22.12.2016; Bureau of Labor Statistics, Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey, 04.01.2017; Binyamin Appelbaum, “U.S. Household Income Grew 5.2 Percent in 2015, Breaking Pattern of Stagnation”, in: The New York Times, 13.09.2016.

2 David H. Autor / David Dorn / Gordon H. Hanson, “The China Shock: Learning from Labor Market Adjustment to Large Changes in Trade”, in: NBER Working Paper No. 21906 (2016), 37; Justin R. Pierce / Peter K. Schott, “Trade Liberalization and Mortality: Evidence from U.S. Counties”, in: NBER Working Paper No. 22849 (2016), 1.

3 Bureau of Labor Statistics, Employment and Unemployment among Youth Summary, 17.08.2016; Alyssa Davis / Will Kimball / Elise Gould, “The Class of 2015: Despite an Improving Economy, Young Grads Still Face an Uphill Climb”, in: Economic Policy Institute, Briefing Paper 401, 27.05.2015.

4 National Center for Education Statistics, Tuition Costs of Colleges and Universities; Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Consumer Credit, G.19 (2016); Shahien Nasiripour, “Student Loan Defaults Drop, but the Numbers Are Rigged”, in: Bloomberg, 28.09.2016.

5 Derek Thompson, “A World Without Work”, in: The Atlantic July/August (2015); Josh Bivens / Lawrence Mishel, “Understanding the Historic Divergence Between Productivity and a Typical Worker’s Pay: Why it Matters and Why it’s Real”, in: Economic Policy Institute, Briefing Paper 406 (2015), 3; Lawrence Mishel / Elise Gould / Josh Bivens, “Wage Stagnation in Nine Charts”, in: Economic Policy Institute, 06.01.2015; Peter H. Lindert / Jeffrey G. Williamson, Unequal Gains: American Growth and Inequality since 1700 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016); Congressional Budget Office, Trends in Family Wealth 1989-2013 (August 18, 2016).

6 Pew Research Center, Public Uncertain, Divided over America’s Place in the World, 05.05.2016, 19.

7 Pew Research Center, Modern Immigration Wave Brings 59 Million to U.S., Driving Population Growth and Change Through 2065: Views of Immigration’s Impact on U.S. Society Mixed, September 2015; D’Vera Cohn, It’s official: Minority babies are the majority among the nation’s infants, but only just, Pew Research Center, 23.06.2016.

8 Samuel Huntington, Who Are We? The Challenges to America's National Identity (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2004), 41; Stan Greenberg / James Carville / Erica Seifert, Inside the GOP: Report on focus groups with Evangelical, Tea Party, and moderate Republicans, 03.10.2013, 18.

9 Randy Krehbiel, “State House sends affirmative action ban to voters”, in: Tulsa World, 27.04.2011; Vanessa Williamson / Theda Skocpol / John Coggin, “The Tea Party and the Remaking of Republican Conservatism”, in: Perspectives on Politics 9 (2011), 32-35.

10 Alexander Zaitchik, The Gilded Rage: a Wild Ride through Donald Trump’s America, 37; Michael I. Norton / Samuel R. Sommers, “Whites See Racism as a Zero-Sum Game That They Are Now Losing”, in: Perspectives on Psychological Science 6 (2011), 215–218.

11 Ruy Teixeira / William H. Frey / Robert Griffin, States of Change: The Demographic Evolution of the American Electorate, 1974–2060 (2015), 14-15; Anne Case / Angus Deaton, “Rising morbidity and mortality in midlife among white non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st century”, in: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112, 08.12.2015, 15078–15083; Carol Graham / Sergio Pinto, Unhappiness in America: Desperation in white towns, resilience and diversity in the cities, Brookings Institution Report, 29.09.2016.

12 Justin Gest, The New Minority: White Working Class Politics in an Age of Immigration and Inequality (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), 16-17 and 21-22; Michael Tesler, “How racially resentful working-class whites fled the Democratic Party – before Donald Trump”, in: The Washington Post, 21.11.2016.

13 Roberto Stefan Foa / Yascha Mounk, “The Signs of Deconsolidation”, in: Journal of Democracy 28 (2017), 5-15; Nathaniel Persily / Jon Cohen, “Americans are losing faith in democracy – and in each other” in: The Washington Post, 14.10.2016.

14 Lydia Saad, Government Named Top U.S. Problem for Second Straight Year, Gallup, 04.01.2016; Gallup, Congress and the Public; Tammy Weber / Emily Swanson, “Poll: Americans happy at home, upset with federal government”, in: Associated Press, 16.04.2016.

15 Juan J. Linz, “The Perils of Presidentialism”, in: Journal of Democracy 1 (1990), 51-69; Pippa Norris, “Why American elections are flawed (and how to fix them)”, in: Harvard Kennedy School Research Working Paper Series (2016), 12-13; Sanford V. Levinson, “America's founders screwed up when they designed the presidency. Donald Trump is exhibit A”, in: Vox, 08.11.2016; Christian Caryl, “Let’s Face It: The U.S. Constitution Needs a Makeover”, in: Foreign Policy, 11.11.2016.

16 YG Network, Room to Grow: Conservative Reforms for a Limited Government and a Thriving Middle Class (2014), 107-112.

17 Martin Gilens / Benjamin I. Page, “Testing Theories of American Politics: Elites, Interest Groups, and Average Citizens,” in: Perspectives on Politics 12 (2014), 564-581; Francis Fukuyama, “America in Decay,” in: Foreign Affairs 93 (2014), 5-26.

18 Michael Barber / Nolan McCarty, “Causes and Consequences of Polarization”, in: Jane Mansbridge / Cathie Jo Martin (eds.), Negotiating Agreement in Politics (Washington, D.C.: American Political Science Association), 21; Matt Grossmann / David A. Hopkins, “How different are the Democratic and Republican parties? Too different to compare”, in: The Washington Post, 08.09.2016.

19 Norman J. Ornstein / Thomas E. Mann, “The Republicans waged a 3-decade war on government. They got Trump”, in: Vox, 18.07.2016.

20 Amanda Taub, “The Rise of American Authoritarianism”, in: Vox, 01.03.2016; Josh Clinton / Carrie Roush, “Poll: Persistent Partisan Divide Over ‘Birther’ Question”, in: NBC News, 10.08.2016.

21 W. Lance Bennett / Shanto Iyengar, “A New Era of Minimal Effects? The Changing Foundations of Political Communication”, in: Journal of Communication 58 (2008): 707-731.

22 Pew Research Center, Public Uncertain, Divided over America’s Place in the World http://www.people-press.org/2016/05/05/public-uncertain-divided-over-americas-place-in-the-world/, April 2016), 47-48.

23 George Edwards III, Persuasion is not Power: the Nature of Presidential Leadership, Paper prepared for delivery at the Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, Chicago, Illinois, 29.08.2013-01.09.2013, 21-26; John R. Zaller, The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinion (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1992).

About the Author

Dr Jack Thompson is a Senior Researcher in the Global Security Team at the Center for Security Studies (CSS). He holds a PhD from the University of Cambridge, a MA from the Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced Studies, and a BA from the University of St. Thomas. Before joining CSS, he worked at universities and/or think tanks in Ireland, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands.

No comments:

Post a Comment