By David Siman-Tov, Gabi Siboni and Gabrielle Arelle for Institute for National Security Studies (INSS)

In this article, David Siman-Tov et al highlight how elections are vulnerable to cyberattacks and other information operations, and how such weaknesses leave democratic nations open to the influence of foreign powers. Our authors conclude that the threat posed by such vulnerabilities is such that nations must recognize elections as a form of critical infrastructure. Further, states must protect each competent of electoral processes – including the media, public discourse, political parties and the voting system itself – if they are to preserve the health of their democracy.

In this article, David Siman-Tov et al highlight how elections are vulnerable to cyberattacks and other information operations, and how such weaknesses leave democratic nations open to the influence of foreign powers. Our authors conclude that the threat posed by such vulnerabilities is such that nations must recognize elections as a form of critical infrastructure. Further, states must protect each competent of electoral processes – including the media, public discourse, political parties and the voting system itself – if they are to preserve the health of their democracy.

This article was originally published by the Institute for National Security Studies (INSS) in Volume 3, Number 1 of Cyber, Intelligence and Security in December 2017.

The Russian interference in the presidential elections in the United States and in France raises questions about the need and ability of democratic countries to protect their election processes. This article indicates the importance of relating to elections in a democratic country as both critical infrastructure and as a critical process, and it presents the threats to elections posed by both cyber and cultural developments. This article addresses the reality in which the extensive use of social networks and direct communications channels enables foreign entities to significantly influence the democratic process—without crippling the voting systems—by introducing outside influence into the political discourse. This constitutes a new challenge to democratic countries, which warrants thinking and re-organization.

Introduction

The fundamental values of democratic countries are liberty, equality, participation, and civil rights. One of the main characteristics of a democratic country is the holding of general, free elections that take place at intervals as prescribed by law. Elections are the ultimate expression of the democratic process and constitute a key component of building the public’s confidence in a country and the faith of its citizens in its institutions.

In recent years, we have seen attempts of external interference and subversion of the election processes in many democratic countries throughout the world through cyberattacks. Cyber threats to the election process in democratic countries may be categorized as threats that aim to disrupt the process through technological tools designed to corrupt information systems and the polling and voting systems, and as material threats to democratic institutions by sullying their good name and by undermining the public’s faith in them. While the first category of threats is well known, and countries are well prepared to contend with them, the second—which is more abstract—is a new type of threat that requires appropriate consideration and analysis.

A report by the American intelligence community that was submitted to the US president in January 2017 assessed that Russia conducted an extensive campaign to undermine the chances of Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton and to promote Republican candidate Donald Trump in the 2016 presidential elections, using both covert cyberattacks and overt efforts to influence public opinion. According to the assessment, Russian cyber agents had hacked the Democratic Party’s computers already back in July 2015 and used information that they had collected during this intrusion.1 This incident is added to additional reports of Russia’s suspected cyber intrusions into government entities in Europe as well, and the disruption of election campaigns there.2 Russia was also suspected of a failed attempt to interfere in the presidential elections in France, with the aim of undermining the election of Emmanuel Macron by publicizing information on the internet that had been stolen from his election headquarters (some of which might have been fake).3

Another case of interference in foreign election campaigns is the exposure of people who were behind the rigging of elections in Latin America. Andrés Sepúlveda—who claimed that he led a team of hackers who had spent the last decade trying to rig the results of elections in Latin American countries like Mexico—said that his team had installed spyware in the computers of opposition offices, stole election campaign strategies, and manipulated social media to create false waves of enthusiasm or derision.4

There is a clear difference between the two cases described above: a world power was apparently behind the first case and attempted to influence the results of the presidential elections in the United States and in France. Private individuals who had been recruited by political rivals were behind the second case.

This article focuses on the first type of threat, that of interference, which we define as “strategic cyber political subversion.” This article discusses the vulnerabilities in a democratic country’s election process that enable foreign interference and analyzes the components of the process and their vulnerabilities to cyberattacks. This article also presents the elections as a critical process, the disruption of which is liable to undermine a country’s democratic stability and the public’s faith in democratic institutions altogether.

Between Critical Infrastructure and Vital Cyber Processes

From the American perspective, critical infrastructure is essential systems that constitute the foundation of American society and that support its security, economy, and health systems. This definition relates to sixteen categories of systems and agencies for which the American government is responsible for guaranteeing their physical and cybersecurity. These categories are the chemical industry, which includes the pharmaceutical, agrochemical, and special chemical industries; commercial infrastructure; communications; manufacturing industries, such as the metal industry; energy; dams; security industries for the manufacture and maintenance of war materials and military systems; emergency services; financial infrastructure; the food and agriculture sector; government infrastructure; health systems; information systems; nuclear infrastructure; transportation infrastructure; and the water infrastructure.5

In Israel, cyber defense is critical for any public infrastructure, whether under government or private ownership, and that defense encompasses physical protection as well as security of its information and computer systems.6 Infrastructure is defined as being critical when harm to it is liable to lead to socio-economic damage that could potentially disrupt the state’s economic or social stability or its security. For the most part, critical infrastructure has three main characteristics: symbolic importance; the state’s functional dependence on them, to the extent that any damage could lead to prolonged impairment and harm to the population or economy; and interactions with other infrastructure.7 In recent years, additional entities such as internet service providers and part of the financial sector have been added to the traditional definition of critical infrastructure in Israel (electricity, communications, railways, water and fuel lines, aviation, and so forth). A committee chaired by the head of the National Cyber Bureau determines which infrastructure should be defined as critical and it requires legislative amendments. Critical infrastructure must comply with national cyber defense regulations. Regulations are enacted—with input from critical infrastructure entities—by the Information Security Authority in the Israeli Security Agency. A considerable portion of the Information Security Authority’s authority is being transferred to the National Cyber Security Authority. Other public services, such as education, health, law, and the election campaigns in Israel, are not defined as critical infrastructure that require direction and guidance from the competent authorities; nevertheless, the Central Elections Committee in Israel receives guidance from the National Cyber Authority.

Demands have been made recently in the United States to update the definition of critical infrastructure and to include additional entities and processes that are vulnerable to cyberattacks, such as election campaigns, research bodies, and academia. These demands are due to the sharp rise in the use of the internet and computerized systems in all sectors (public, business, government, private, infrastructure, and academia), which warrant the reclassification of these infrastructures, given the sensitivity of complex systems that are based on communications and computer infrastructure, including elections systems.8

Democratic Election Process – Main Cyber Threats

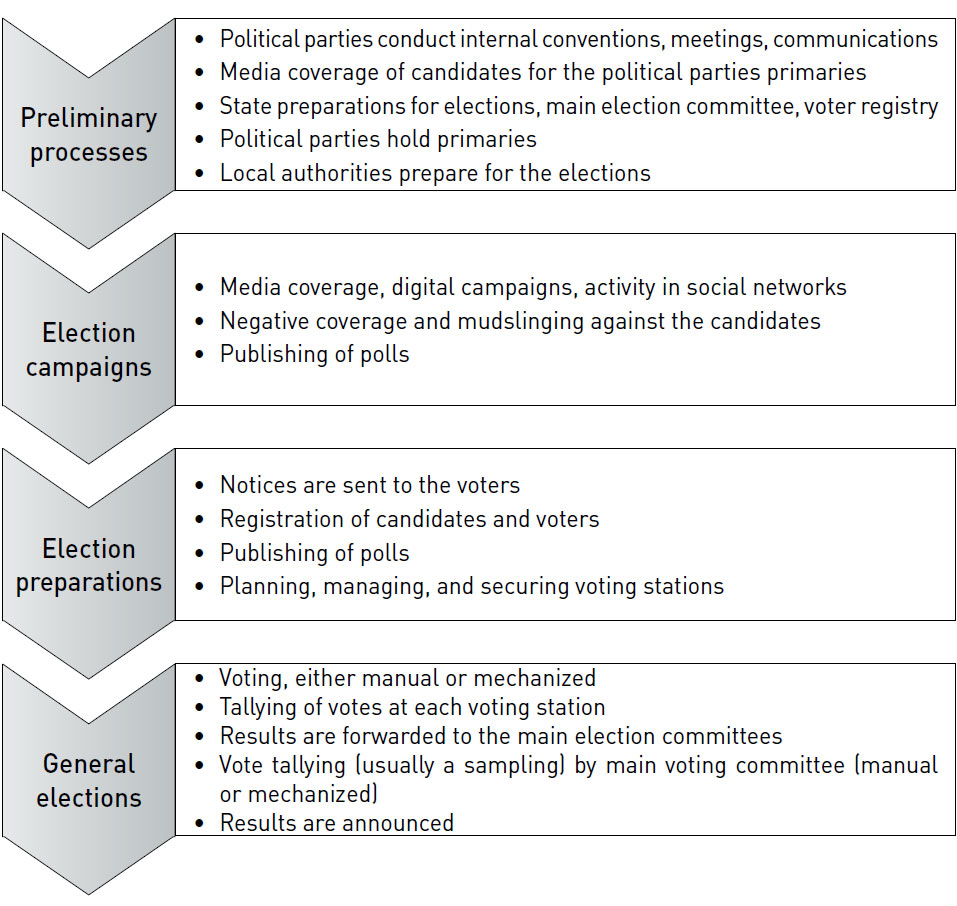

A democratic election is a process composed of various interacting players and entities. Components of the democratic process increasingly use infrastructure, including cyberspace. The election process is comprised of four stages that proceed in chronological order, as shown in the diagram below. The major cyber threats to this process, against which countries must defend themselves, are attacks on infrastructure, the collection of information about candidates and political parties, and attempts to influence public opinion.

Cyber Weaknesses in the Election Process

Disrupting, altering, and forging of information bases

The government departments that are responsible for recording and saving the personal information of the country’s citizens and companies have been undergoing advanced digitization processes and streamlining in recent decades with the installation of computerized systems for registering and managing records. These systems are extremely vulnerable to cyberattacks, as was proven in the US states of Georgia, Illinois, and Arizona.9 In these three states, cyber intrusions into the e-voting machines were discovered, which could have led to the theft or exposure of the details of about 21 million US citizens. Identity theft and leaking and/or altering voters’ details could have ramifications on the entire democratic process.

Exposing a campaign to corrupt citizens’ data or causing harm to their voting stations (such as by giving false information about the location of the voting station, potentially disqualifying votes) is liable to adversely affect the public’s faith in the election system. One example occurred during the general elections in Canada in 2011, when pranksters telephoned citizens and gave them incorrect information about the location of their voting station, apparently with the aim of diminishing voters’ motivation to exercise their right to vote.10

In Israel, voters’ details are not just saved in the databases of the State and the Elections Committee but are also forwarded to every political party running for election. This situation creates vulnerability in securing voters’ information, although, to date, no attempts to disrupt elections in Israel have yet been exposed. This raises the issue of how to guarantee the proper use and supervision of the voters’ database in a reliable way.

Hacking of voting systems on election day

Voting during elections, whether by manual or mechanized voting, entails verifying personal details, tallying of the votes at the voting stations, and transferring the data to the main system. Hacking of one of these processes will cause significant harm to the entire process. The electronic systems that facilitate the election day process include various services: registration at a voting station and providing the right to vote; electronic voting at the voting station (either using a touch screen or a personal card); remote electronic voting through internet access only; and tallying the votes. The growing use of electronic voting systems has positive and negative implications: on the one hand, an electronic system should increase citizens’ participation in elections (since they can vote from home or from mobile phones); on the other hand, such a system has a higher risk of being hacked and manipulated and requires the investment of resources to secure and maintain it.11

A study conducted by the Institute of Cyber Security in the United States, which researches cyber technologies for critical infrastructure, found that the direct-voting system together with the Op Scan system that scans the voting cards; the systems that assess the data; and the computerized databases do not provide terminal-to-terminal encryption or an adequate security solution. It was also discovered that these systems are operated on unprotected computers at many US voting stations, which can be easily hacked. The study also determined that opponents with appropriate capabilities could find a way to manipulate local and political parties’ systems, whose level of security is even lower than the state’s general election systems, by uploading malware to the computers; disabling the systems; and stealing, exposing or altering information.12

Altering the tally of votes

The mode of tallying votes at the close of election day varies from country to country, according to the voting method. In Israel, voting in national elections is done manually, through ballots tallied by hand in the voting stations and input into an electronic system that computes the regional voting percentages to obtain a final national calculation. In 2014, a seminar held in Canada conducted a comparative assessment of the main electoral systems in Britain, Canada, the United States, Australia, New Zealand, and India and reached the conclusion that, in the future, all of the bodies involved in election processes will need to contend with the challenges of the development of network-based systems and their implications on the election campaigns, including securing the on-line or remote voting processes, the databases, and the vote-tallying systems.13

Many publications in the United States have discussed the possibilities for influencing the vote-tallying systems and forging the cards that operate the electronic direct-voting systems. Thus, for example, an electronic direct-voting system has been introduced in some parts of the United States, identification is verified by using a personal chip card, and voting is conducted on a touch screen. This system saves the data and generates a printout that is produced at the close of election day, which includes the breakdown of votes at each voting station. It became evident that by using a forged card, it was possible to change the data on the screen, alter votes, delete votes, and even remove candidates.14 Furthermore, despite the identification by card, these systems may be remotely hacked to manipulate the tally of votes and even their segmentation. Electronic voting, which is done via computer with internet access, is even more vulnerable to hacking, fraud, and subversion of the general election process.15

Destroying Public Trust by Influencing the Content of the Public Discourse

As stated, besides the election process, there are additional factors that constitute the basis for the public’s faith in the country and its institutions. According to one researcher, several characteristics constitute the key components of the public’s faith in the political establishments in a democratic country: independent media, active public opinion, an independent judicial system, a fair standard of living (health services, housing, education, and employment), and free elections. Subverting these components is liable to significantly affect people’s faith in the country’s institutions and public services in general as well as their own personal sense of security in their country.16

The emergence of new arenas of discourse and communications in recent years (particularly social media) has led to the development of a wide-scale political and public discourse that addresses a more diverse audience than the traditional media and enables direct contact with citizens and voters. This change has led to the increased use of the internet as an arena for recruiting activists and support, for transmitting messages, and for managing election campaigns. The internet is no longer the domain of marketing and advertising gurus alone; rather, we have witnessed electoral candidates who have become increasingly active on various media channels, as well as hostile countries that seek to influence public opinion on the social networks and the internet.17

Consequently, the protection of democratic processes requires that we add to the direct threats defined above some additional threats that occur in the conscious space, which are liable to critically impact the democratic process and, in turn, the public’s confidence in it. In this context, a dilemma arises relating to the need to differentiate between legitimate courses of action in a political battle and illegitimate interference by foreign entities. Defense against such threats does not relate to the direct cyber aspects (defending the terminal stations, servers, networks, and so forth) but rather to interference in the content of the messages within the political discourse. The question raised concerns the limits of free speech: Does it encompass only a country’s citizens and leaders or also outside sources—such as foreign countries and terrorist organizations—when their interference is not legitimate and is intended to thwart democratic proceedings? In other words, perhaps we can reconcile ourselves to the phenomena of manipulations, lies, and rumors as a legitimate part of the political battle inside a country, but we cannot accept foreign interference that is liable to undermine the citizens’ confidence in their country’s institutions, which leads to their destabilization.

The structure of social networks enables content to “go viral” by extensive sharing, which increases its dissemination and its publication based on activity and the reactions that the content generates, and thus magnifies its exposure and publicity. Therefore, it is enough to have a few hundred users (real or fake) who create content targeting a specific audience for the message to “go viral” and awaken a public discourse that the traditional communications media will join. All the above indicates that it is important to examine how we can prevent outside sources from manipulating a country’s democratic processes—general elections, processes within political parties, judicial processes, and so forth.

As stated, in recent years, western countries have experienced several attempts to influence the political discourse, which have been attributed to Russia. There are those who believe that attempts to influence and interfere in election campaigns in other countries reflect Russia’s intent to undermine citizens’ faith in the democratic process in general and in electoral systems in particular, while fabricating a sense that the system is incapable of protecting its citizens’ privacy and of ensuring a genuine democratic process.18 In recent years, it appears that Russia has indeed been doing its best to influence public opinion in countries where it has interests, such as in Ukraine and in the Baltic republics, as well as in Germany, the Netherlands, and France, which represent the most dominant countries in the European Union. Examples of this influence include the cyber intrusion into the Bundestag in Germany in 2015 for collecting intelligence, which would harm the ruling political party, and the attempt to interfere in the referendum in the Netherlands in April 2016, which was held because of a demand to terminate the European Union’s 2014 trade agreement with Ukraine. A poll that examined the positions of voters who opposed the agreement found that most of the rationale they gave was false, not based on facts, and apparently had come from Russian propaganda.19 In addition, there were reports that Russia was trying to influence Britain’s exit from the European Union (“Brexit”); the election campaign in the United States in favor of Donald Trump; and unsuccessful attempts to influence the elections in France a few months later.

The examples mentioned above demonstrate the rise in the dissemination of political or strategic information via social networks or websites that specialize in exposing information (such as “WikiLeaks”) in order to influence public opinion and public discourse. Entities seeking to influence the discourse and the results of elections can do so by exposing information, whether real or fake, with the right timing. Such exposure is designed to create doubt about a candidate’s suitability and to spread rumors that will harm a person’s candidacy. These examples also show how elections can be influenced by the spreading of fake news, publicizing false surveys, creating media buzz about a false report that has implications on foreign policy, and leaking of personal and embarrassing information about candidates. All these can influence democratic processes and relations between countries.

The recognition of the growing use of this strategy requires a comprehensive discussion about expanding the defense measures against this threat in democratic countries.20 Moreover, even if the technological aspects of the election process will be fully protected, it will still be possible to influence the entire democratic process. This is one of the key challenges in defending any election campaign: it is not enough to protect technological infrastructure and systems; a defense response is also needed for the entire discourse against outside anti-democratic corruption. If, in the past, the attacker had sought to disrupt communications and computer systems, now, in the era of the new threat, the attacker is actually interested in ensuring that these systems continue to operate so that the attacker can inundate them with manipulative messages.

Factors Threatening the Democratic Election Process

The cyber threat to election campaigns can be expressed by the interference of world powers or foreign countries, international criminal or terrorist activities. The types of threats are differentiated by identifying the attacker, the motivation for the attack, its sophistication and complexity, and the available resources for executing the attack. In order to protect the election proceedings or any other critical infrastructure, risk management needs to include an analysis of those players who are motivated and able to subvert the democratic election process.21 An article that analyzed the sensitivity of the election process following the Russian attempts at interference, examined, inter alia, which of the various players could carry out a cyberattack against components of the US election system. Included among them were hostile countries, internal rivals, and individual hackers, the latter acting out of ideological motives, such as members of “Anonymous” or “WikiLeaks,” or funded organizations with political ideologies that work to influence the elections through massive campaigns on social networks and among young people.22

The motives of rival countries for interfering in the election campaigns of another country vary according to the target of the attack. One motive can be the desire to undermine the public’s sense of personal security and faith in the entire democratic process. The understanding that public opinion has an impact on how policies are set motivates rival countries to incite citizens against the democratic framework and, mainly, against the government and the politics within the country. Another motive for interfering in another country’s election campaign is the desire to influence the outcome of the elections. Therefore, the interfering forces will invest their resources in several channels: influencing public opinion through propaganda, for example, by planting “trolls” who operate throughout the internet against the establishment and sometimes against the internet community; disseminating negative and inflammatory reactions to particular information; hacking of websites; spamming; subverting public opinion and faith in the system; and leaking sensitive information about rival candidates. Another motive may also be to engage in espionage and intelligence collection, including the theft of sensitive information about the candidates or about their election headquarters, as was done during the summer of 2016, when e-mails were leaked from the Democratic Party’s convention.

Conclusions

This article presents the threats to election campaigns, as well as the cyber and cultural developments and underlines the importance of recognizing election campaigns as critical infrastructure and processes. The conclusion is that an overall defense of the election process is needed because its external influence is liable to completely undermine the public’s faith in the political establishment in their country and democratic values altogether. Leaders in Israel’s national cyber organization have demonstrated their understanding of the importance of defending the computer systems of the Central Elections Committee and the database of voters, and they agree that a legislative amendment may be necessary to define these systems as critical infrastructure; however, it appears that the need to protect the political discourse from external interference is still not yet understood.

An election campaign is a “soft spot” in a democratic country, and an attack on it is liable to influence both the country and the candidates. Western countries should consider expanding their approach and the modes of response to threats to the democratic proceedings, such as by safeguarding the media discourse and defending political parties, coupled with protecting election committees and voting mechanisms. Defending only one component of the overall system will not be enough, however. The attempts to influence elections by exposing and publicizing information stored in the computer systems of political parties or candidates, some of which have apparently succeeded, demonstrate that the defense of these systems must be enhanced. Those attempts also give rise to the question about the country’s responsibility to lead the cyber defense of political institutions.

This article does not discuss responses to threats facing the election system in democratic countries, as it intends at this initial stage to enable a discussion about these threats, particularly those endangering the political discourse in democratic countries. Directing the spotlight on external threats emphasizes the role that a country’s security establishment has in thwarting threats of political subversion. This also requires the security establishment to define the threats and to delineate them in a way that will protect freedom of expression on one hand and will also protect the political discourse from illegitimate interference on the other.

The challenge of defending the election process and all other democratic processes, such as the rule of law and freedom of expression, is not just safeguarding the operation of the infrastructure; rather, it also encompasses the preservation of the public’s faith in the system, which is a far more evasive achievement that may be undermined in a variety of different ways. Thus, this article presents the need—for which there is wide consensus— to defend the network of computers that operates the election system. In addition, it addresses the necessity of protecting the political discourse from external interference, which seeks to undermine the public’s faith in the entire democratic system but is still not widely recognized, because, inter alia, it challenges the democratic principles, such as safeguarding freedom of speech (in social media and the traditional media).

Notes

1 Office of Director of National Intelligence, “Background to Assessing Russian Activities and Intentions in Recent US Elections: The Analytic Process and Cyber Incident Attribution,” Intelligence Community Assessment, January 6, 2017.

2 “Not only in the United States: Russia Interferes with Elections in Europe,” Ynet, December 10, 2016 (in Hebrew).

3 Eric Auchard and Felix Bate, “French Candidate Macron Claims Massive Hack as Emails Leaked,” Reuters, May 6, 2017.

4 Jordan Robertson, Michael Riley, and Andrew Willis, “How to Hack an Election,” Bloomberg, March 31, 2016, https://www.bloomberg.com/features/2016-how-tohack-an-election.

5 The definition was taken from the website of the US Department of Homeland Security: https://www.dhs.gov/critical-infrastructure-sectors.

6 Roy Goldschmidt, “Cyber Space and Defending Critical Infrastructure,” The Knesset, the Research and Information Center, 2013 (in Hebrew).

7 Lior Tabansky, “Critical Infrastructure Protection Against Cyber Threats,” Military and Strategic Affairs 3, no. 2 (November 2011): 61–78.

8 Kate O’Keefe and Byron Tau, “U.S. Considers Classifying Election System as ‘Critical Infrastructure,’” Wall Street Journal, August 3, 2016.

9 Dan Goodin, “US E-Voting Machines are (still) Woefully Antiquated and Subject to Fraud,” Ars Technica, November 7, 2016.

10 Paul G. Thomas and Lorne R. Gibson, “Comparative Assessment of Central Electoral Agencies,” Elections Canada (May 2014), http://www.elections.ca/content.aspx?section=res&dir=rec/tech/comp&document=p4&lang=e#ftn10.

11 Goodin, “US E-Voting Machines.”

12 James Scott and Drew Spaniel, “The Painfully Vulnerable Election System and Rampant Security Theater,” ICIT Blog, Institute for Critical Infrastructure Technology, October 24, 2016.

13 Thomas and Gibson, “Comparative Assessment of Central Electoral Agencies.”

14 Goodin, “US E-Voting Machines.”

15 Dimitris A. Gritzalis, Secure Electronic Voting (New York: Springer, 2003).

16 Prof. Marco Meier, lecture, “Cyber, Politics and Elections” conference, Yuval Ne’eman Workshop for Science, Technology and Security, Tel-Aviv University, January 17, 2017.

17 Azi Lev-On and Erez Cohen, Connected: Politics and Technology in Israel (Jerusalem: Israel Political Science Association, 2011) (in Hebrew).

18 Keir Giles, Russia’s ‘New’ Tools for Confronting the West, Research Paper (London: Chatham House, Royal Institute of International Affairs, 2016).

19 Anne Appelbaum, “The Dutch just Showed the World how Russia Influences Western European Elections,” Washington Post, April 8, 2016.

20 “Emerging Cyber Threats to the United States,” Testimony of Frank J. Cilluffo, director of the Center for Cyber and Homeland Security before the US House of Representatives’ Committee on Homeland Security, and the Subcommittee on Cybersecurity, Infrastructure Protection, and Security Technologies, February 25, 2016, http://docs.house.gov/meetings/HM/HM08/20160225/104505/HHRG-114-HM08-Wstate-CilluffoF-20160225.pdf.

21 Goldschmidt, “Cybernetic Space and Defense of Critical Infrastructure.”

22 Scott and Spaniel, “The Painfully Vulnerable Election System.”

David Siman-Tov is a researcher at the Institute of National Security Studies.

Dr Gabi Siboni is a senior researcher at the Institute of National Security Studies and heads its Cyber Security Program.

No comments:

Post a Comment