By SYDNEY J. FREEDBERG JR.

CRYSTAL CITY: The Army needs revolutionary technologies from robot tanks to a long-range super-rifle, the Chief of Staff said today — and it can get them without repeating the mistakes that doomed high-tech programs in the past. By reforming the acquisition bureaucracy, embracing commercial technology and rigorously prototyping new tech to work out bugs, Gen. Mark Milley said, the Army can improve 10-fold on its current weapons without falling into the pitfalls that doomed its last attempt to leap ahead, the canceled Future Combat System.

CRYSTAL CITY: The Army needs revolutionary technologies from robot tanks to a long-range super-rifle, the Chief of Staff said today — and it can get them without repeating the mistakes that doomed high-tech programs in the past. By reforming the acquisition bureaucracy, embracing commercial technology and rigorously prototyping new tech to work out bugs, Gen. Mark Milley said, the Army can improve 10-fold on its current weapons without falling into the pitfalls that doomed its last attempt to leap ahead, the canceled Future Combat System.

An Army captain briefs the Chief of Staff, Gen. Mark Milley, at Fort Hood.

“I’m not interested in a linear progression into the future (with) incremental improvements,” Gen. Milley told an Association of the US Army breakfast here. “That will end up in defeat on a future battlefield.”

“What I’m talking about …. call it 10X, call it leap-ahead, (is) radical improvement in current capabilities,” he said. “We want to be so dominant, so good, so capable, that our enemies would never dare attack the United States, and that our enemies know for sure that, if they did, they would lose.”

“People say, ‘oh, FCS, Comanche,'” Milley said, invoking the litany of canceled Army programs of the past. “No, no, no, (this is a) different animal. We’re talking about 10X capabilities that don’t exist in the real world right this minute but they will, and we’re doing a lot of engineering, R&D, S&T, to make them exist, and we’re working closely with industry to do that.”

But FCS was all about getting radical improvements from new technology that wasn’t quite ready, I pointed out during Q&A. How do you reach for similar ambitions without falling into the same traps?

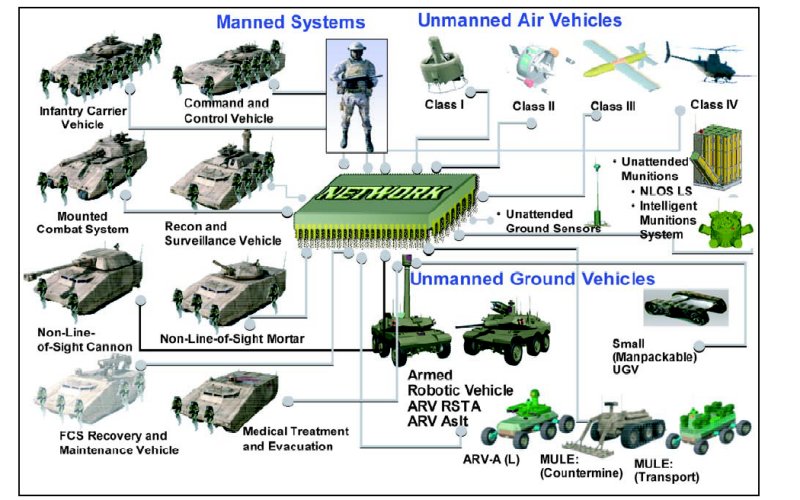

Army graphc

Army slide showing the elements of the (later canceled) Future Combat System

No Repeat of FCS

FCS isn’t the only example of the Army trying to revolutionize its technology, Milley replied: The Army has done this right before. When the current tank was introduced in the 1980s, he said, “an M1 tank was worth 10 M60A3s.” There were similar gains with the other “Big Five” programs of the 1980s — the M1 Abrams and M2 Bradley armored vehicles, the Patriot missile, the UH-60 Black Hawk transport helicopter, and the AH-64 Apache attack helicopter: “Those systems were radical advancements,” Milley said.

(One thing Milley didn’t mention that’s worth pointing out. The Big Five were managed as five complementary but separate programs. When related programs failed, like the DIVADS anti-aircraft gun, they could be killed without dragging down the whole modernization effort. By contrast, FCS was already sprawling to start with and grew to include 20 different manned vehicles, robots, and other technologies under a single program with a single contract, part of the early 2000s vogue for a “lead systems integrator.”)

M1 Abrams tanks in Iraq

Today’s M1A2 SEP V3 may look like 1980’s M1 but it boasts major improvements to the main gun, targeting system, communications and other electronics. After four decades of gradual upgrades, however, we’re up against fundamental limits of turret, hardware, suspension, and power supply.

“The M1 tank is fine, for now, for right this minute,” Milley said. “But we should at the same time not think the M1 tank or the Bradley or any of these other vehicles— (e.g.) the Apaches — are going to be okay 10, 15, 20 years from now. Because I am absolutely certain there are technologies happening in the world today that…will make these systems obsolete and out of date, and they will lose.”

Not every new technology you’d want actually exists, Milley emphasized: There’s no new lightweight armor that allows, say, a 20-ton vehicle to have the protection of a 70-ton Abrams. However, he said, “there are areas in which you can get 10X relative to current capabilities. One of them for example is robotics. Robotics is here.”

From self-driving cars in California to smart bullets being tested at Fort Benning, Milley argued, there are many revolutionary technologies already near the level where industry could start building prototypes for the Army to test.

Might one model for this approach be the Army-led Future Vertical Lift program, which is building two competing aircraft before it picks a design, one reporter asked after the event? “I think so, Milley said. “There are some things, because they’re very unique to the military, they’re not going to be available (commercially). But a lot of the stuff that we use is potentially available out there. Buy it, try it, test it out, prototype it. If it doesn’t work, don’t use it. If it does, go for it, and cut to the chase.”

As the Army reorganizes its acquisition system, Milley said, “one of the principles we’re trying to accentuate with this Futures Command and the cross-functional teams etc. is the idea of prototyping.”

Russian Uran-9 armed unmanned ground vehicle

So what kinds of technologies does Milley want to see prototyped? Many are electronic, some are hardware, and others combine them.

Drone Capability For Aircraft & Armored Vehicles: Milley wants both the Future Vertical Lift aircraft, which will replace existing helicopters, and the Next-Generation Ground Vehicle, which will replace tanks and/or Bradleys, to be “optionally manned.” That means they could be crewed by humans or operated by artificial intelligence, depending on the danger and complexity of the mission.

“Future vehicles, air or ground, are going to have to be dual use, so the commander on the ground can….make a determination as to whether he wants this assault to be manned or unmanned,” Milley said. “Does he want to attack Hill 101 with robots or does he want to do it with manned vehicles?”

Milley didn’t address how difficult that dilemma might be. High danger and low complexity, like blazing the first trial for a minefield, argues for automation. Low danger and high complexity, like peacekeeping in a crowded city, calls for humans. The hard part is missions that are both dangerous and complex, like urban combat.

Matrix-Style Training For Urban Warfare: Army trainers have to catch up to the dramatic advances in virtual reality and gaming, Milley said. While simulations will never replace live field exercises with actual troops on both sides, he emphasized, simulations are a lot cheaper, which means you can do a lot more of them. They can also simulate environments you just can’t replicate on the ground, like a sprawling megacity.

As urban population rises, Milley, said, “wars of the future, in my mind, will likely be fought in urban areas.” That’s hard to replicate in traditional training grounds, but not in virtual reality. “We can put a set of goggles on you… boom! And now you’re in City X, and it looks exactly like you’re actually walking down the street,” Milley said. He envisioned a future when “every company in the Army” could have its own multi-player training simulation suite where troops “could fight all day long.”

Precise, Long-Range Artillery Shells & Rifle Bullets: Long-Range Precision Fires is both the Army’s top modernization priority and the name of its new heavy missile system to succeed ATACMS (itself a contemporary of the Big Five). But there are other ways to achieve long-range precision than missiles, which are expensive packages of electronics, explosives, and rocket motors that you can only use once. By contrast, a gun provides reusable targeting and propulsion for an infinite number of individually cheap projectiles.

“I’m talking about a 10X capability for ground forces to really reach out and touch (the enemy), not with missiles, but with bullets,” Milley said. “It’s not physically here right this minute but we’re working very, very hard.” This sounds a lot like the Hyper-Velocity Projectile (HVP), which can fire from existing howitzers, but Milley only smiled when asked about that specific system.

US Army soldiers already carry overwhelming loads of equipment

Milley offered more detail on a next-generation personal weapon. “We have a good rifle now,” he said, dismissing decades of debate on the M-16. But ongoing research on new optics, propellants, and other technologies at Fort Benning, the Army’s infantry center, makes possible radically improved small arms, he said, with “much greater” range, lethality, and accuracy.

“They’ve done some proof of principle on it, it is real, not fantasy, and industry is moving out quickly,” Milley said. “We expect that with appropriate funding, we should be able to have this particular weapon in the not too distant future.” (This could be an evolution of the XM25, which is a kind of precision-guided grenade launcher, but it seems more like a super rifle firing solid bullets).

This potential weapon is just one of the many improvements the Army is exploring for the often-neglected foot soldier, Milley said, from exoskeletons to clothing. “From head to toe, the best helmet, the best SAPI (armor) plates, the best goggles, the best communication equipment, the best pistol, the best rifles, the best machineguns, the best everything, all the way down to the boot,” he said, “they should have the best bar none.”

No comments:

Post a Comment