Harsh V. Pant

Harsh V. Pant says the Chinese offers of economic cooperation and infrastructural development in India’s own backyard are reshaping regional relationships, and are a test of India’s own global ambitions The past year has marked a turning point in Sino-Indian relations in more ways than one. If 2017 began with India taking a strong stance against China’s ambitious “Belt and Road Initiative”, it ended with China’s tightening grip in South Asia. In between was the 73-day long Doklam stand-off between Asia’s two giants. The year’s events underscore the challenges for this bilateral relationship in ways few would have anticipated in the recent past. India and China increasingly jostle with each other for strategic space. And South Asia is fast emerging a theatre of Sino-Indian rivalry.

Harsh V. Pant says the Chinese offers of economic cooperation and infrastructural development in India’s own backyard are reshaping regional relationships, and are a test of India’s own global ambitions The past year has marked a turning point in Sino-Indian relations in more ways than one. If 2017 began with India taking a strong stance against China’s ambitious “Belt and Road Initiative”, it ended with China’s tightening grip in South Asia. In between was the 73-day long Doklam stand-off between Asia’s two giants. The year’s events underscore the challenges for this bilateral relationship in ways few would have anticipated in the recent past. India and China increasingly jostle with each other for strategic space. And South Asia is fast emerging a theatre of Sino-Indian rivalry.

China made an ambitious move in December by hosting the first trilateral meetingwith the foreign ministers of Pakistan and Afghanistan. Afghan Foreign Minister Salahuddin Rabbani and Pakistan Foreign Minister Khawaja Asif joined their Chinese counterpart Wang Yi in Beijing, where they reportedly agreed to work together to tackle the threat of terrorism. From China’s perspective, such terrorism is intricately linked to the security of its restive Xinjiang region. Beijing also gave a push to the Afghanistan peace process, in limbo since 2015.

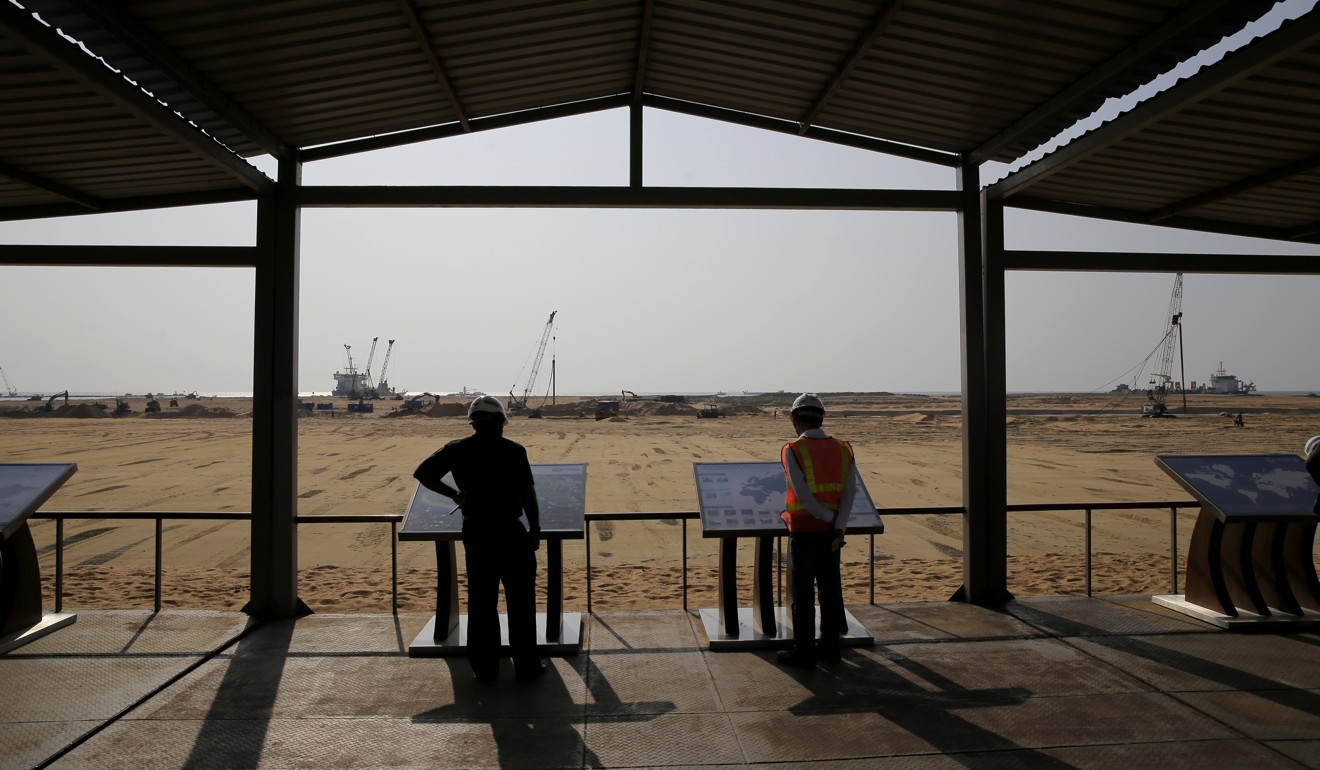

Garnering much attention is the suggestion that China and Pakistan consider extending their US$57 billion China-Pakistan Economic Corridor to Afghanistan. The Chinese foreign minister publicly expressed hope that the economic corridor could benefit the whole region and act as an impetus for development, but China’s moves were aimed at India, which has been steadfast in its refusal to accept the economic corridor.

Over the years, China has managed to tighten its economic bonds with India’s neighbours. The Maldives became the second country in South Asia, after Pakistan, to enter into a free trade agreement with China late last year. After Xi Jinping’s visit to the Maldives in 2014, the first by a Chinese president, the nation officially became part of the “21st century Maritime Silk Road”. China quickly expanded its economic profile in the Maldives by building mega infrastructure projects, including development of Hulhule and a bridge connecting Male to the country’s main international airport.

India’s ties with Nepal have also entered a difficult phase with the decisive victory of the coalition of the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist Centre), and the Communist Party of Nepal (Unified Marxist Leninist), led by Khadga Prasad Sharma Oli. Soon after his victory, Oli visited the border with China in Rasuwagadhi and declared that the Rasuwagadhi-Kerung border point, the only transit point between Nepal and China, would be upgraded to international standards. This is an implicit challenge to India, which has been Nepal’s principal link to the world.

Oli blamed the blockade along the Nepal-India border in 2015 by Madhesi groups on India, making his intention of taking his country closer to China clear. In November last year, the government of prime minister Sher Bahadur Deuba had cancelled a major US$2.5 billion hydroelectric project awarded to Chinese state company China Gezhouba Group, much to Beijing’s annoyance. The new Communist government in Nepal is likely to reverse that decision.

Beijing is also looking into the possibility of connecting Kathmandu to Tibet’s capital Lhasa via railways, at an estimated cost of US$8 billion, as part of the Belt and Road Initiative.

While China seems to be enjoying an upswing in relations throughout South Asia, not everything is going in its favour. The much-hyped China-Pakistan Economic Corridor project confronts serious problems. Pakistan reportedly rejected China’s offer of assistance for the US$14 billion Diamer-Bhasha Dam, asking Beijing to take the project out of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor so that Pakistan can build the dam on its own. Pakistan realised that the tough conditions imposed by Beijing pertaining to the dam’s ownership, operation and maintenance costs, as well as security, made the project politically and economically untenable. The Hambantota Port in Sri Lanka offers a cautionary example: China lent money and later took over the indebted port. Pakistan therefore gravitated towards self-financing.

Differences also emerged over the use of the Chinese renminbi in Pakistan along the lines of the US dollar. Pakistan rejected this demand as well, arguing that common use of the renminbi in any part of Pakistan, exchangeable like the dollar, had to be on a reciprocal basis.

The initial euphoria surrounding the economic corridor has given way to a more realistic appraisal of the project’s costs, with Beijing and Islamabad each reassessing the terms of their engagement. While China is demanding greater autonomy and security in operations, Pakistan finds it difficult to accede to most of these demands. Growing voices in Pakistan suggest that China may be a bigger beneficiary from the economic corridor than Pakistan. The expectation is that China will engage in its modus operandi of importing goods and labour for the projects at the expense of the local market, with Islamabad left carrying the burden of paying interest on loans to Chinese banks well into the future.

Such disputes may settle or intensify. But Sino-Pakistan relations are unlikely to be downgraded by either side as both view them as critical in managing India.

Smaller states in South Asia have long used the China card to balance India’s overweening regional presence. Now with China’s heft in global politics at an all-time high, the temptation to leverage Beijing’s clout in bilateral ties with India is even greater. Yet geography is a reality that cannot be changed. As New Delhi asserts itself as a global power, it must manage not only its immediate neighbourhood with greater strategic vision but also monitor China’s growing clout in South Asia. This, after all, is just the beginning of Sino-Indian jousting in South Asia.

Harsh V. Pant is a distinguished fellow at Observer Research Foundation, New Delhi, and professor of international relations at King’s College London. Reprinted with permission from

This article appeared in the South China Morning Post print edition as: the game begins

No comments:

Post a Comment