By SYDNEY J. FREEDBERG JR.

WASHINGTON: Over the next few weeks, US Army leaders will make major decisions about the Futures Command they’re standing up this summer. The new organization will be the biggest departure in how the Army buys weapons in 40 years. Important as it is, however, it’s also just one of many changes the Army must make in 2018. One of the unsung stories of 2017 was how the US Army made big down payments towards progress on multiple fronts: new weapons, new concepts, new organizations. But reinventing a huge institution takes years, and the post-Cold War Army in particular has tended to take two steps forward and 1.9 steps back. Under the irrepressibly energetic Gen. Mark Milley, who became chief of staff in 2015, the largest service seems to be overcoming inertia at last. The challenge is keeping the momentum.

WASHINGTON: Over the next few weeks, US Army leaders will make major decisions about the Futures Command they’re standing up this summer. The new organization will be the biggest departure in how the Army buys weapons in 40 years. Important as it is, however, it’s also just one of many changes the Army must make in 2018. One of the unsung stories of 2017 was how the US Army made big down payments towards progress on multiple fronts: new weapons, new concepts, new organizations. But reinventing a huge institution takes years, and the post-Cold War Army in particular has tended to take two steps forward and 1.9 steps back. Under the irrepressibly energetic Gen. Mark Milley, who became chief of staff in 2015, the largest service seems to be overcoming inertia at last. The challenge is keeping the momentum.

Milley has made two big bets that should start to pay off in 2018. One is Army Futures Command, which will pull together talent from across the service’s vast bureaucracy into a single, streamlined organization to develop new weapons and new ways to use them. While the command won’t open its doors until this summer, the core is already in place: eight Cross Functional Teams, led by one- and two-star generals, each taking on a different aspect of Milley’s Big Six modernization priorities. That said, the chief of staff’s chief collaborator, Army undersecretary Ryan McCarthy, told Breaking Defense that the teams are still getting up to speed. They’ll start making their mark in earnest, he said, with the 2020 budget — the foundations for which are laid (you guessed it) in 2018.

Milley’s other big modernization move is an in-depth review of the service’s network programs, the electronic nervous system that binds the Army together from foxhole to headquarters. Launched in 2017, the review already led him to curtail the service’s flagship WIN-T program (Warfighter Information Network – Tactical) for being too cumbersome, unreliable, and vulnerable for high-speed warfare against a high-tech foe. In 2018, the review faces the much harder task of coming up with a working alternative.

An Army soldier sets up a highband antenna.

The current plan includes both a short-term push for off-the-shelf stopgaps this year and next — which is hard enough — and a long-term comprehensive solution for the entire Army — which is even harder. Imagine setting up a home wifi network, only for almost a million people scattered across the world, while the Russians try to hack and jam you.

The current plan includes both a short-term push for off-the-shelf stopgaps this year and next — which is hard enough — and a long-term comprehensive solution for the entire Army — which is even harder. Imagine setting up a home wifi network, only for almost a million people scattered across the world, while the Russians try to hack and jam you.

To protect the network, and maybe mess with the adversary’s, the Army is investing heavily in cyber and electronic warfare. For the long-neglected electronic warriors in particular, Army cyber chief Maj. Gen. Patricia Frost said in December, “this is a tremendous year of delivery, because we’re going to deliver prototypes to the field,” building on off-the-shelf gear already urgently deployed to Europe. Said Frost: “We’re not going to wait six, ten years to build the perfect piece of kit.”

New Year, New Weapons

Not all the seeds bearing fruit in 2018 were planted by Gen. Milley. In the long, arduous process of weapons development — the very thing Futures Command is supposed to speed up — many of them began under his predecessor, Gen. Ray Odierno, or even before.

A BAE Systems M2 Bradley modified with sensors and weapons to shoot down aircraft and drones.

One big example: After at least a decade and a half of trying, and well behind other countries such as Russia and Israel, the US Army approved Active Protection Systems to shoot down incoming missiles that can penetrate existing armor. To get a brigade of M1 Abrams heavy tanks outfitted the Israeli-made Trophy APS by 2020, the Army needs to start fielding gear this year. Meanwhile, testing continues with smaller APS on lighter vehicles, the Bradley and the Stryker. The Army’s also exploring anti-aircraft variants of both these vehicles, as well as fielding upgunned Strykers to defeat light armored vehicles.

In addition to upgrades, the Army’s also building an all-new armored vehicle: the Mobile Protected Firepower (MPF) light tank, meant to accompany airborne troops and other light infantry where Strykers and Bradleys can’t. The formal Request For Proposals came out in November and the Army will choose a winner in early 2019. That means this year is crunch time for the competing design teams as they refine their prototypes to meet the exact requirements of the RFP. SAIC, for instance, said in October they’d offer a Singaporean chassis with a Belgian turret: This year they actually have to put the two together and make it work.

The Army is also the lead sponsor of the Future Vertical Lift program to replace existing helicopters with much faster, longer-ranged machines. FVL had a breakthrough in 2017: One competitor, Bell’s V-280 Valor, made its first flight (see video above). But Bell will only start flight testing in earnest this year — while the rival Sikorsky-Boeing SB>1 Defiant, a more radical design, will have to prove it can fly at all.

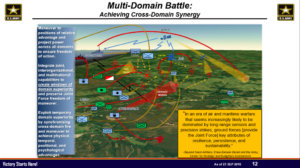

An Army slide attempting to explain the service’s new Multi-Domain Battle concept

All these new vehicles, like the new network electronics, are necessary for the Army’s alarming vision of future combat, in which armored and airborne forces must stay constantly on the move just to survive. After 16 years fighting savage but low-tech insurgents, Milley has decisively reoriented the Army towards sophisticated, high-tech nation-states. Above all, that means Russia, which he has clearly and consistently identified as the No. 1 threat. (At the same time, Milley’s also stood up two advisor brigades to preserve counterinsurgency skills). The Army’s concept for future combat, Multi-Domain Battle, first came out in late 2015, but it matured significantly in 2017: rolling out a full-length concept document, getting buy-in from the Air Force, and standing up an experimental unit to test tactics.

All these new vehicles, like the new network electronics, are necessary for the Army’s alarming vision of future combat, in which armored and airborne forces must stay constantly on the move just to survive. After 16 years fighting savage but low-tech insurgents, Milley has decisively reoriented the Army towards sophisticated, high-tech nation-states. Above all, that means Russia, which he has clearly and consistently identified as the No. 1 threat. (At the same time, Milley’s also stood up two advisor brigades to preserve counterinsurgency skills). The Army’s concept for future combat, Multi-Domain Battle, first came out in late 2015, but it matured significantly in 2017: rolling out a full-length concept document, getting buy-in from the Air Force, and standing up an experimental unit to test tactics.

The thinkers behind Multi-Domain Battle, incidentally, will probably become part of the new Futures Command. (They’re currently under Training & Doctrine Command, TRADOC). The plan is to bridge old bureaucratic divides and bring together the Army’s futurists, its technologists, its acquisitions experts, and its veteran warriors. That kind of teamwork is what it will take to move beyond today’s significant but scattered successes to the comprehensive modernization that future warfare demands. 2018 is the year that starts — or doesn’t.

No comments:

Post a Comment