By Daniel Keohane

Much of the current discussion about European defense, no matter the format, revolves around the ‘big three’: France, Germany and the UK. However, Daniel Keohane argues that Italy and Poland deserve more attention as they are both frontline states for EU and NATO security. As a result, in this article Keohane provides an insight into Poland and Italy’s national defense policies by comparing their 1) geostrategic outlooks; 2) defense operations, capabilities and spending; and 3) positions on military cooperation through NATO and the EU.

Much of the current discussion about European defense, no matter the format, revolves around the ‘big three’: France, Germany and the UK. However, Daniel Keohane argues that Italy and Poland deserve more attention as they are both frontline states for EU and NATO security. As a result, in this article Keohane provides an insight into Poland and Italy’s national defense policies by comparing their 1) geostrategic outlooks; 2) defense operations, capabilities and spending; and 3) positions on military cooperation through NATO and the EU.

Italy and Poland are both frontline states for EU and NATO security. They also represent the two main operational priorities for European military cooperation: defending NATO territory in Eastern Europe, and intervening to stabilize conflict-racked countries south of the EU.

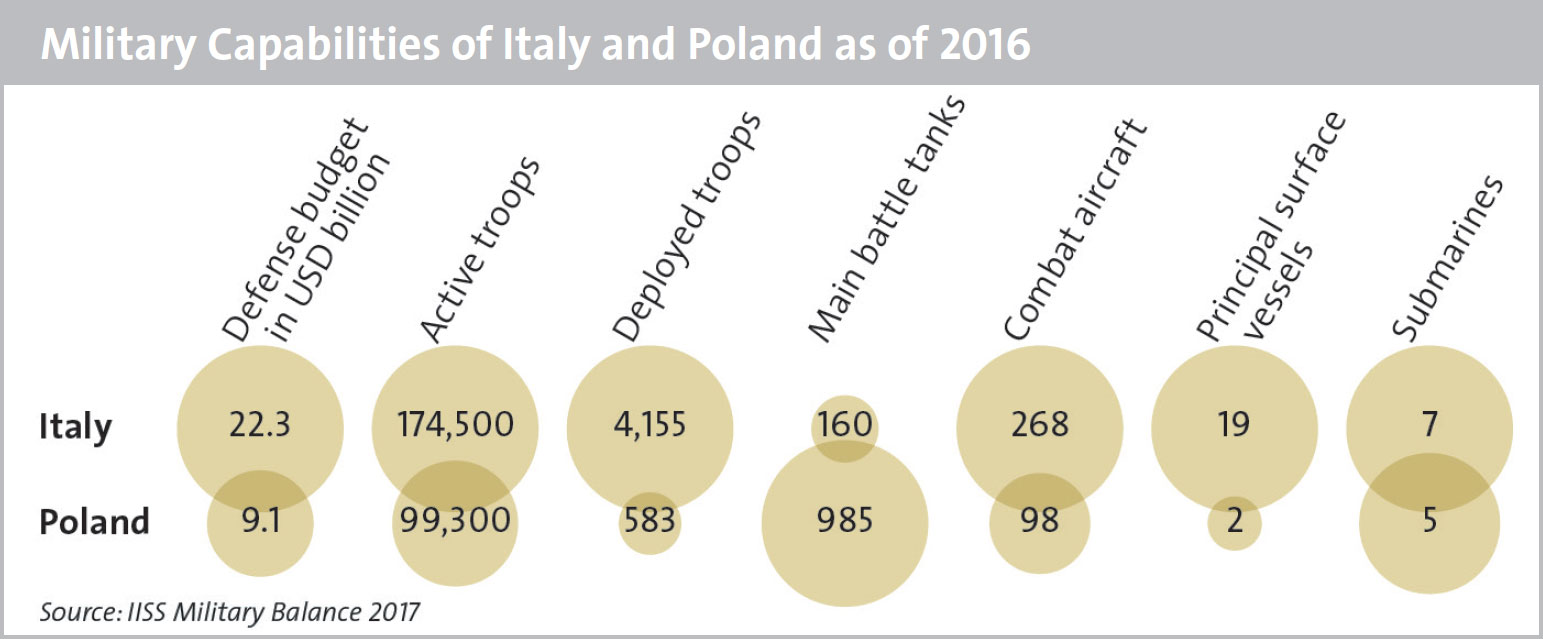

Towards the end of 2015, a few defense experts raised their eyebrows at a Credit Suisse report on the future of globalization. Contained within this wide-ranging assessment was a short analysis of global military power, ranking the top 20 countries in the world. Weighing six elements of conventional warfare, the Credit Suisse analysts considered Poland a stronger military power than Germany, and Italy came ahead of the UK.

The Credit Suisse analysts compared indicators such as active personnel, tanks, aircraft, attack helicopters, aircraft carriers, and submarines. In their explanation of their conclusions, the analysts singled out Germany, which came 18th out of 20; it ranked considerably lower than expected because of relatively smaller or non-existent capabilities in certain categories, such as aircraft carriers and submarines.

Notwithstanding those conclusions, much of the current discussion about European defense (whether through NATO, the EU, or other formats) revolves around the positions of the “big three”: France, Germany, and the UK – the leading European military spenders at NATO. However, opinions in those other two major European powers, Italy and Poland, deserve more attention. In some ways, this comparison may seem politically counter-intuitive, since on paper they would not appear to have much in common. For example, Italy is a founding member of both NATO and the EU, whereas Poland only joined NATO in 1999 and the EU in 2004.

However, it is interesting to compare their national defense policies because they are both frontline states for EU-NATO security, and represent the two main operational priorities in European military cooperation: defending NATO territory in Eastern Europe, and intervening to stabilize conflict-racked countries south of the EU.

Italy has received 75 per cent of migrants and refugees coming across the Mediterranean into the EU this year – over 110,000 people, according to the International Organization for Migration. As Elisabeth Braw of the Atlantic Council has noted, this has placed considerable strain on the Italian coast guard and navy, which rescued around 25,000 migrants between January and June of this year.

Poland worries greatly about the military threat from Russia, following Moscow’s 2014 annexation of Crimea and subsequent warfighting in eastern Ukraine. A year ago, Russia deployed Iskander-M ballistic missiles (nuclear-capable rockets with a range up to 500 kilometers) to Kaliningrad, its Baltic exclave situated between Poland and Lithuania. Part of the joint Russia-Belarusian “Zapad” military exercise in September 2017 took place in Kaliningrad, as well as in Poland’s neighbor Belarus. Estimates vary greatly as to how many armed services personnel took part in “Zapad 2017”, but some experts estimated the total number to be as high as 100,000, whereas others suspect it was lower.

Understandably, the Polish and Italian defense policies must prioritize either defensive capabilities or an interventionist stance, partly because with relatively limited resources, they must prioritize. By comparison, NATO estimates that the UK will budget USD 55 billion, France USD 44 billion, and Germany USD 43 billion for defense this year. In contrast, Italy will budget USD 22.5 billion and Poland USD 10 billion.

Geostrategic Outlooks

After France, Germany, and the UK, Italy is the largest absolute European defense spender, by some distance, of the remaining members of NATO and the EU, and the country has been an active contributor to NATO, UN, and EU operations over the last 20 years. In 2015, Italy replaced its 2002 white book with a new defense white paper that lays out Italy’s strategic vision, operational priorities, and spending intentions. The document assigned a central role to an interest-based approach to international security, and is unambiguous about the need to use military force, alongside the vital role of the military instrument for deterrence purposes.

Due to Italy’s economic difficulties in recent years and more austere government budgets, there have been fewer resources available for Italy’s national defense effort. Italian defense spending as a percentage of GDP fell from 1.3 per cent in 2011 to 1.1 per cent in 2017 (according to NATO estimates). The 2015 white paper, therefore, is very clear on what Italy’s strategic and operational priorities should be. In particular, the “Euro-Mediterranean” region is highlighted as the primary geo-strategic focus for Italy. This region is conceived in broad terms, covering the EU, the Balkans, the Maghreb, the Middle East, and the Black Sea. But it is clear that Italy, which had previously sent troops as far afield as NATO’s mission in Afghanistan, will now primarily worry about its immediate neighborhood.

This is probably not surprising, given the turbulence that has affected some of these regions in recent years, especially North Africa and the Middle East. Turmoil in Libya, for example, has greatly contributed to the large numbers of migrants being smuggled across the Mediterranean to Italy. Interestingly, Italy not only intends to contribute to international coalitions (whether NATO, the UN, or the EU) in this Euro-Mediterranean space. It is also prepared to lead high-intensity, full-spectrum crisis management missions across this region. In other words, even if the geostrategic priorities of Italian defense policy are more narrowly defined than those of other large European powers, its external operational ambitions remain relatively robust.

Poland’s geostrategic and operational approach contrasts quite markedly from Italy’s. For one, Poland is primarily geographically focused on Eastern Europe, particularly the military threat from Russia. Furthermore, its operational priority is to improve both its national defensive efforts and those of NATO, rather than contributing to robust external missions. Poland, for example, did not participate in NATO’s air bombing campaign in Libya in 2011. The Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014, following the Russo-Georgian war in 2008, strongly reinforced a perception in Poland that Warsaw must invest more in its national defense, including through NATO.

The 2017 Polish Defense Concept, a strategic review published in May, pointedly states that “the number one priority was the necessity of adequately preparing Poland to defend its own territory.” The first threat and challenge listed in the concept paper is the “aggressive policy of the Russian Federation”, followed by an “unstable neighborhood on NATO’s eastern flank”.

To be fair, the Polish paper is not myopic, and the third priority is NATO’s southern flank, to which Poland expects to “be obliged to support Allies in various endeavours”. It adds that: “Unlike in the past, we want Polish contributions to be significant, but with no enduring negative effects to our national defence capabilities”. Italy is not ignoring NATO’s eastern flank either. Rome has contributed to Baltic air policing, for example, and will be the lead nation for NATO’s Very High Readiness Task Force (VJTF) during 2018 – the alliance’s spearhead force for operational readiness.

Operations, Capabilities, Spending

Even though Italian defense spending is equivalent to only 1.1 per cent of its GDP, just over half of NATO’s much-trumpeted headline goal, Italy is one of Europe’s biggest contributors to international operations. The Istituto Affari Internazionali in Rome says that Italy sent over 6,000 armed forces personnel to international missions during 2016. This is almost double Germany’s number, which deployed roughly 3,300 during 2016, according to the German defense ombudsman. The bulk of those Italian soldiers operated across Africa and the Middle East, reflecting the priorities set out in the 2015 Italian defense white paper.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, given Italy’s focus on the Mediterranean Sea, Rome is currently investing around EUR 5.4 billion in naval platforms, such as littoral combat ships, based on a 2015 parliamentary decree (Legge Navale). More generally, contained in Italy’s 2017 budget law (Legge di Bilancio) is a plan to invest some EUR 46 billion in a mix of infrastructure, disaster relief, and territorial security over the next 15 years. Within that envelope, around EUR 12 billion in new funding is earmarked for defense, including military capabilities and technologies. This plan will draw from a special fund in the budget of the Ministry of Economic Development rather than the Ministry of Defense.

As a percentage of GDP, Poland spends almost twice as much as Italy on defense. Moreover, Polish President Andrzej Duda signed a law in October 2017 committing Poland to spend an impressive 2.5 per cent of GDP on defense by 2030 (currently, Greece has the highest European proportion at NATO, with 2.3 per cent). The same law also includes a plan to increase Poland’s armed forces from the current 100,000 personnel to 200,000. Some 50,000 of those will belong to a new voluntary “Territorial Defense Force”. Referring to the new defense law, Polish Defense Minister Antoni Macierewicz rather ambitiously stated: “The Polish army will within ten years gain the capability of stopping every opponent.”

In addition, Poland was already implementing an ambitious national military modernization plan, having committed itself to spending around USD 37 billion on military modernization by 2025. This money is being spent on upgrading armored and mechanized forces, anti-seaborne threat systems, new helicopters, air and anti-missile defense systems, submarines, and drones.

Poland is also exploring a number of bilateral initiatives to deepen military relations with other European NATO members. For example, a German battalion has been placed under a Polish brigade, while the two countries agreed in 2016 to strengthen their naval cooperation, including establishing a joint “submarine operating authority”. In November 2016, Poland and the UK announced their ambition to agree on a bilateral defense treaty. Italy too, has been developing its bilateral cooperation with some European NATO members. These have included joint projects with the UK for developing military helicopters and with Germany on submarine systems. Currently, the most notable new Italian bilateral venture aims to develop joint naval capabilities and industrial capacity with France.

The EU and NATO

Both Poland and Italy say that they have robust military intentions, whether to defend national territory or to contribute to international interventions. Even so, both want help from their allies, whether for countering Russian missiles or in coping with cross-Mediterranean migrants.

Traditionally, Italy has been strongly committed both to NATO solidarity and to European integration. The 2015 white paper places the EU and NATO on an equal footing in terms of Italy’s contribution to international security. Moreover, NATO’s role is primarily defined in defensive and deterrence terms, both for the defense of national territory and Europe as a whole: “only the Alliance between North America and Europe is able to dissuade, deter and provide military defence against any kind of threat”.

The EU is presented as important for Italy in two ways. First, Italy intends to pursue cooperation on capability development more vigorously with other European allies, and the EU – specifically the European Defense Agency – is a vital conduit for such cooperation. Second, working through the EU is also important for carrying out external operations, since EU defense policy forms part of broader EU foreign policy and mainly performs out-of-area missions.

For example, at a summit in Brussels in October 2017, Italian Prime Minister Paolo Gentiloni asked other EU governments to help more with stemming migrants, including sending a mission to police Niger’s border with Libya, on top of current EU efforts such as naval operations. Italy, like Germany, is more relaxed than many other Europeans about discussing some shared European sovereignty on defense matters, such as a stronger role for the European Commission in defense market and military research issues.

In addition, Italy is prepared to make proposals on EU military cooperation. Rome, for instance, proposed that Europeans create a multinational military force a year before French President Macron suggested the same in his Sorbonne speech in September 2017. Italy was also one of the four signatories of an October 2016 letter (along with France, Germany, and Spain) that called for the instigation of the Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) mechanism in the EU treaties, which allows a core group of EU countries to cooperate more closely on military matters. Italy sees no real or potential contradiction between its firm commitment to NATO and its wholehearted support for deeper EU military cooperation.

After some hesitation in Warsaw, Poland indicated in November 2017 that it would participate in the EU’s PESCO initiative, which is due to be formally launched in December 2017. Some Polish politicians have advocated for a “European army” in the past. Speaking to the Financial Times in 2006, Lech Kaczynski, then Poland’s president, suggested creating a 100,000-strong EU army, tied to NATO and available for use in “global trouble spots”. The Polish government has long called for stronger NATO defenses; and its members were greatly reassured by US President Donald Trump’s endorsement of NATO’s mutual defense commitment in Warsaw in July 2017.

However, Polish enthusiasm for military cooperation through NATO in recent years has not always translated into strong support for complementary efforts through the EU. The EU-NATO balance on defense matters now appears to be a binary choice for some experts in Warsaw. Andrzej Talaga from the Warsaw Enterprise Institute, for example, described French President Macron’s September 2017 proposals for a stronger EU military intervention capacity as “suicidal” for Poland, because they would weaken NATO’s Collective defense. The 2017 Polish defense concept puts this differently: “All EU actions in the security domain should complement and enrich NATO operations in a non-competitive manner.” Moreover, in the paper, that observation is preceded by a statement on the central importance of NATO for Poland, “which is key to our policy of collective defense”.

Both Warsaw and Rome say that they want close coordination between the EU’s military efforts, like PESCO, and NATO processes, such as its Defense Planning Process (NDPP). In addition, both Italy and Poland are keen supporters of NATO “nuclear sharing”, the deployment of US nuclear forces and capabilities in five countries in Europe. Although some in Warsaw would support such a move, US nuclear forces cannot be deployed on Polish territory because of restrictions in the 1997 NATO-Russia Founding Act. However, since 2014, Poland has participated with conventional forces (such as F-16 fighter jets) in NATO’s annual Support of Nuclear Operations With Conventional Air Tactics (SNOWCAT) exercise. Italy hosts US nuclear forces at its Aviano airbase, and Italian Tornado aircraft can carry US nuclear weapons based at the Ghedi Torre airbase near Brescia.

However, despite some similarities in their national outlooks, at the EU table, Poland is not always immediately enthusiastic about what Italy wants (e.g., PESCO or a multinational European military force), whereas at the NATO table, Poland would like more of what Italy has (i.e., a strong US military presence and nuclear sharing). Furthermore, because of their different priorities and approaches, in many ways Italy and Poland represent the two sides of Europe’s defense coin. Comparing the defense policies of Poland and Italy shows that European military cooperation (whether through NATO or the EU) cannot fully contribute to European security until European governments realize that they need to be collectively able to both defend their territories and intervene abroad.

No comments:

Post a Comment