By Owen Frazer and Christian Nünlist

How has the concept of Countering Violent Extremism (CVE) developed in conjunction with other ‘soft’ approaches to terrorism, such as peace and development efforts? In this analysis, Owen Frazer and Christian Nünlist respond, before going on to explore 1) five reasons why those who work in the human rights, development and peacebuilding fields have concerns about CVE; and 2) the possibility of Switzerland creating its own national Countering Violent Extremism strategy.

How has the concept of Countering Violent Extremism (CVE) developed in conjunction with other ‘soft’ approaches to terrorism, such as peace and development efforts? In this analysis, Owen Frazer and Christian Nünlist respond, before going on to explore 1) five reasons why those who work in the human rights, development and peacebuilding fields have concerns about CVE; and 2) the possibility of Switzerland creating its own national Countering Violent Extremism strategy.

The Concept of Countering Violent Extremism

After the terrorist attacks in Paris, Europe is stepping up repressive measures to combat terrorism. Yet, prevention and the “soft” aspects of counterterrorism measures must also be kept in mind. The concept of Countering Violent Extremism (CVE), in conjunction with peace and development policies, has developed as part of a modern approach to counterterrorism. This creates opportunities for Swiss foreign policy.

Since 2001, there has been a constant increase in the number of victims of violent extremist movements. Groups such as al-Qaida, the so-called “Islamic State” (IS), Boko Haram in Nigeria, and al-Shabaab in Somalia and Kenya have managed to hold their ground despite international counterterrorism efforts. In 2015, terrorist attacks in Europe further demonstrated the threat that violent extremists pose. The notion of Countering Violent Extremism (CVE) gained increasing traction in 2015 among state actors around the globe and has come to be perceived as a crucial component of a sustainable counterterrorism strategy in responding to IS and the phenomenon of so-called Foreign Terrorist Fighters (FTF). Because violent extremism is no longer associated only with individual terrorist attacks, but also with conflicts that have caused tens of thousands of deaths and injuries, CVE fosters closer cooperation and exchange between the security services and actors in the fields of conflict management and prevention.

In 2015, the concept of CVE succeeded in establishing itself in official political jargon. In February, a three-day “CVE summit” took place in the White House, chaired by US President Barack Obama and attended by ministers from nearly 70 countries. This was followed up at the end of September by a high-level meeting on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly with the participation of 100 governments and 120 representatives of civil society and the business sector. UN Secretary-General Ban Ki Moon has announced a “UN Plan of Action to Prevent Violent Extremism”, to be presented at the beginning of 2016.

The idea underpinning CVE is that violent extremists should not be fought exclusively with intelligence, police, and military means. The structural causes of violent extremism must also be tackled, including intolerance, government failure, and political, economic, and social marginalization. As UN Secretary-General Ban recently remarked: “Missiles may kill terrorists. But I am convinced that good governance is what will kill terrorism.” With the promotion of the concept of CVE, US counter-terrorism policy has shifted closer to the approach of the UN, which has long laid strong emphasis on preventive measures and thus prefers the abbreviation PVE (Preventing Violent Extremism).

Los Angeles County sheriffs attend Friday prayers at the Islamic Center of San Gabriel Valley in Rowland Heights, California, engaging with the local Muslim community.

Los Angeles County sheriffs attend Friday prayers at the Islamic Center of San Gabriel Valley in Rowland Heights, California, engaging with the local Muslim community.

David McNew / Reuters

CVE: Origins and Evolution

There is nothing new about the idea that suppression of terrorism must encompass both hard and soft measures. Even though the abbreviation “CVE” (and its alternative, “PVE”) is only now finding its way into political and diplomatic discourse, the concept has some interesting precursors. As early as December 2001, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) at its Ministerial Council Meeting had demanded that global terrorism be countered not only with military and intelligence means, but also by tackling the root causes of terrorism.

The concept of CVE was introduced in Europe after the attacks in Madrid (2004) and London (2005) in response to the fear of homegrown Islamist terrorism. The UK government’s Prevent program is regarded as the first practical example of CVE. From 2005 to 2011, GBP80 million was spent under this program on local projects for the prevention of jihadist radicalization.

The EU’s counterterrorism strategy of 2005 relied on four pillars: To prevent, protect, pursue, and respond. The “prevent” element related to the societal conditions that led to individual radicalization. The UN’s global anti-terrorism approach in 2006 also called for a holistic strategy that encompassed the conditions conducive to terrorism.

Australia, Canada, and the US all adopted national CVE strategies of their own in 2011. France, Finland, Holland, Nigeria, Norway, Spain, and Switzerland have since also drafted national strategies to combat terrorism with a particular focus on the prevention of violent extremism and the resilience of their societies in the face of terrorism. The influence of CVE/PVE is also growing in the field of development aid and international cooperation, particularly in US policy.

Many Terms, No Definition

CVE or PVE refers to the “soft” side of counterterrorism strategies that tackle the drivers which lead people to engage in politically- or ideologically-motivated violence. In practice, the current focus is on violent Islamist movements, but the term can also be applied to other violent groups, ranging from right-wing or left-wing extremists and environmental activists to Buddhist or Hindu nationalists.

The challenge for political decision-makers and practitioners stems from the fact that there are no internationally accepted definitions for either “terrorism” or “violent extremism”. Critics regard the two terms as being synonymous, with “violent extremism” as a cosmetic replacement for the highly politicized term “terrorism”. In July 2005, the US government under then president George W. Bush introduced the term “violent extremism” as an alternative to the much-criticized concept of the “war on terrorism”. The advocates of the concept, however, argue that “violent extremism” refers to something different than terrorism. Both terms describe efforts to achieve political goals by violent means. A possible distinction between the two could hinge on the idea that terrorism involves violence aimed at spreading fear and terror.

The term “radicalization” is often used to describe the process by which an individual becomes a terrorist or a violent extremist. However, this implies a direct link between radicalism or extremism and violence, which risks the stigmatization of non-violent groups. Radicalism should not be viewed as a problem per se: Although radical ideas and ideologies sometimes inspire the worst kinds of atrocities, they can also be positive catalysts of societal change (e.g., the abolition of slavery in the US).

Causes and Countermeasures

Up until now, the focus, both in public discourse and in the academic study of political violence, has been on the personal trajectories of terrorists. The attention given to personal motives and convictions as well as negative experiences of exclusion, rejection, humiliation, injustice, or frustration was a distraction from structural factors that can lead to violent extremism. Since 2005, there has been a deluge of research on “radicalization”, centering on the question of why and how individuals turn into violent extremists and how this can be avoided at an early stage. However, these studies, focused on the micro-level, were unable to identify a typical profile or decisive individual factors. It was found impossible to extrapolate generalizations from the case studies and individual life stories as the motives and ideas that turn individuals into violent extremists are multifaceted and extremely complex.

The concept of CVE/PVE aims to engage with these personal, individual causes at the micro-level. At-risk individuals are identified by family members, religious authorities, social workers, or sports coaches. Telephone helplines like the “Hayat” hot-line in Germany have proven particularly effective in this regard, and are currently being instituted in many European countries. It is hoped that through such measures, violence-prone extremists continue to receive emotional support from their family members as an important alternative reference group, even, if, for example, they happen to be fighting in Syria. This requires that the families are supported with professional counseling.

At the meso-level, focused on the hitherto less studied social milieu of a violent extremist, many programs address the question of how societies can respond with positive alternative voices to narratives and ideas espoused by violent extremists. In this context, disillusioned former violent extremists can play an important and credible role.

On the similarly under-studied macro-level, government actions both at home and overseas play an important role. Such structural drivers of violent extremism include chronically unresolved political conflicts; the “collateral damage” to civilian lives and infrastructure caused by military responses to terrorism; human rights violations; ethnic, national, and religious discrimination; the political exclusion of ethnic or religious groups; socioeconomic marginalization; lack of good governance; and a failure to integrate diaspora communities of immigrants who move between cultures.

These causes must be as resolutely tackled as those at the individual and local levels. Governments must reflect on the role their foreign policies play. Many measures that serve to eliminate breeding grounds for violent extremism are also worthy aims for peace and development policy in their own right, independently of counterterrorism efforts. These include respect for human rights, good governance, strengthening the rights of women, and inclusion in the political, economic, and social spheres.

Areas of Tension

CVE/PVE’s concern with the structural drivers of violent extremism brings it into contact with what has traditionally been the realm of those working on human rights, development, and peacebuilding. Although this linkage is in principle to be welcomed, the concept of CVE/PVE continues to make many active in these fields nervous. There are five main reasons for this:

Firstly, the counterterrorism discourse has long been prone to manipulation by governments that wish to suppress domestic opposition, ignore human rights obligations, limit the space for civil society and curb media freedoms – all in the name of national security. Such policies can themselves become drivers of violent extremism.

Secondly, CVE and PVE programs may lead to the stigmatization of communities. Members of Muslim communities in particular often feel unfairly treated as potential terrorists and fear that these programs are used as pretexts for surveillance and intelligence operations.

Third, CVE/PVE programs risk contradictions with conflict-sensitive approaches that emphasize values such as impartiality. Just like “counterterrorism”, CVE/PVE is a state-driven concept which casts those who oppose the state using violent means as the main problem. This means that in countries experiencing violent political conflict, participation in CVE/PVE initiatives may effectively mean siding with the government in an internal conflict. For development or peacebuilding organizations, civil society groups, religious leaders, or local actors, this may be problematic.

Fourth, CVE/PVE programs have largely refrained from reaching out to local actors who may espouse radical views outside of the “moderate” mainstream, but who are anti-violence. Among at-risk individuals, such people may have more credibility than moderate voices offering value-based “counter-narratives”, particularly when the latter are perceived as backed by the government.

Fifth, the current hype surrounding CVE/PVE, and the associated availability of funding, means that traditional peacebuilding and development programs are in danger of being subsumed to CVE/PVE concerns. There is a worry that instead of assessing whether they have achieved their original goals, programs will be evaluated in terms of their contribution to CVE/PVE. Similar concerns have been voiced by leaders in local communities targeted by CVE/PVE policies. They accuse the government of instrumentalizing them by imposing government-defined objectives, rather than engaging with them to design programs which take into account the concerns and priorities of their communities.

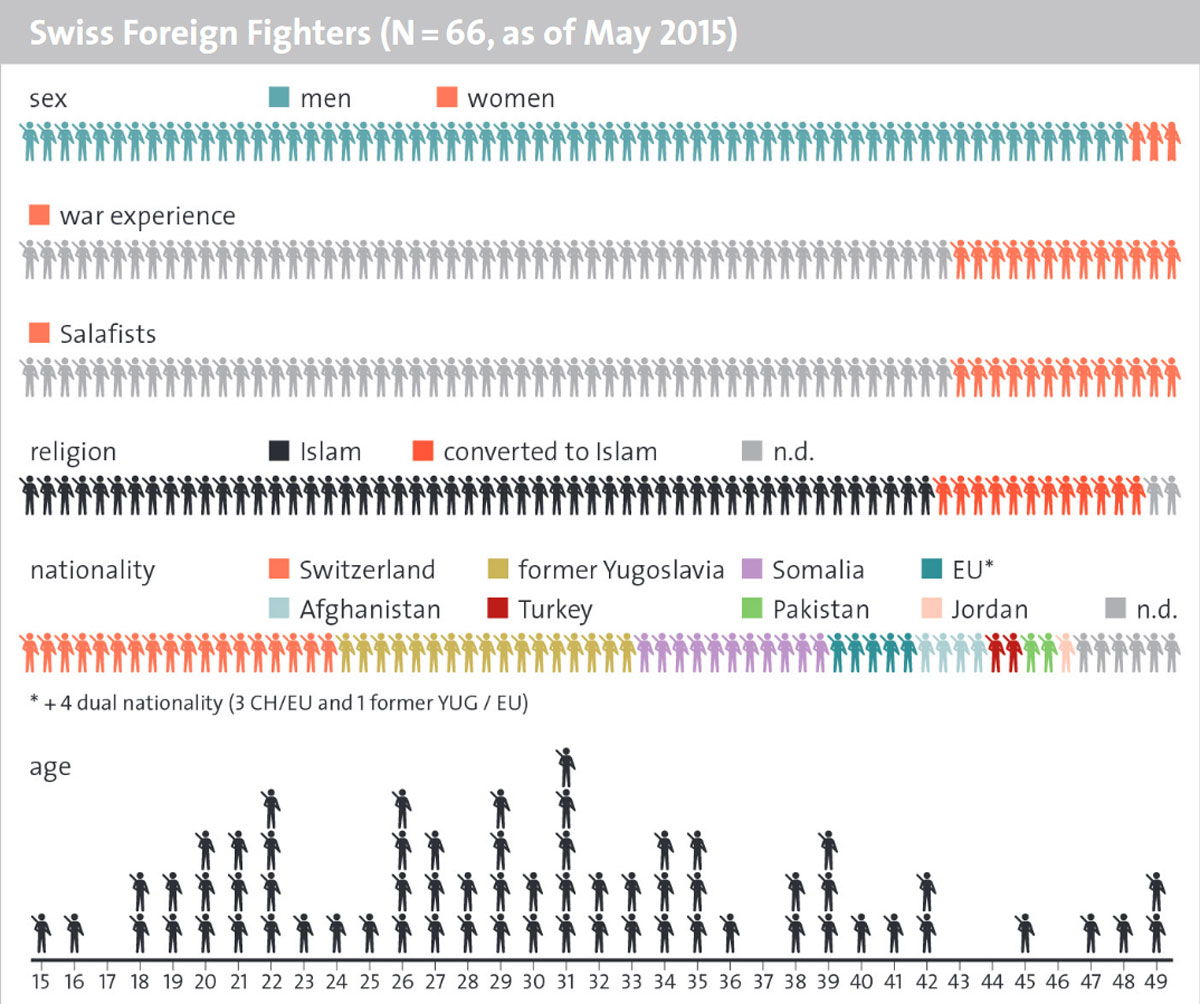

Source: Miryam Eser Davolio et al., Background to Jihadist Radicalisation in Switzerland, Septermber 2015, ZHAW.

What Next?

These challenges have been identified over the course of the “first wave” of CVE programs implemented in the last decade, exemplified by the abovementioned UK Prevent strategy of 2005. Four important conclusions can be drawn for future CVE/PVE approaches. These lessons are likely to be integrated into the announced UN Action Plan to Prevent Violent Extremism, a document which will probably become an important reference point in the development of future action plans at the national level.

First of all, it is important to ensure that strategies are not limited to programs at the individual or community level, but also take into account the structural causes of violent extremism. Secondly, it is vital that programs be tailored to the specific local context. Programs cannot simply be copy-pasted from one context to another.

Third, initiatives with too much government involvement may be counterproductive. A new buzzword in CVE/PVE circles is the “Whole of Society Approach” which includes all relevant actors in CVE/PVE efforts. However, space must be left for communities and civil society actors to develop initiatives of their own and to determine if, and when, state involvement is appropriate, and to what extent. This is particularly important in the case of initiatives aiming to mobilize actors outside of the mainstream. Credible counter-narratives necessarily require a perceptible distance from the government. Fourth, a conceptual distinction is required between programs that are “CVE-specific”, i.e., whose primary aim is to prevent violent extremism, and those that are “CVE-relevant”, i.e., which may have positive side-effects in the sphere of CVE. Not everything that is CVE-relevant needs to be labeled as a CVE program.

PVE in Swiss Politics

In 2015, the phenomenon of so-called “foreign fighters” as well as the CVE summits in the US raised the question of whether Switzerland should develop a national CVE strategy of its own. The Federal Council’s “Counterterrorism Strategy for Switzerland”, published on 18 September 2015, contains numerous elements that evoke the spirit of CVE/PVE. The focus is squarely on prevention, which is why Swiss government representatives prefer the term “PVE” over “CVE”. Swiss efforts for preventing violent extremism can be subdivided into international and national efforts.

Domestically, Switzerland is engaged in four strategic fields of action – prevention, repression, protection, and crisis preparedness. In the field of prevention, Switzerland undertakes concrete measures for violent extremism in the areas of education and (youth) unemployment, integration, religions, social welfare, and protection of both youths and adults. In prisons, youth centers, and places of worship, de-radicalization programs as well as sensitization and violence prevention campaigns are recommended. Such efforts to foster good relations and create awareness of CVE/PVE must not stigmatize nor discriminate against Muslim communities.

In 2015, the “Terrorist Travellers Task Force” (TETRA), created by the Swiss authorities for the purpose of dealing with the phenomenon of foreign fighters, laid out its position on CVE/PVE in two reports: The working group emphasized that existing structures at the municipal, cantonal, and national levels are essentially sufficient for confronting violent extremism as a society-wide challenge. Thanks to strong social and educational structures and good opportunities for integration Switzerland is considered more resilient towards jihadist radicalization than other small countries in Europe (cf. info box).

Extremist Violence in Switzerland (highlighted paragraph)

In Switzerland, violent extremism has largely been associated with right-wing. left-wing, and animal rights extremism, although the the threat has diminished in recent years. According to a CSS study of November 2013, Switzerland is noticeably less affected by jihadist radicalization than other European states due to four reasons: First of all, there are no breeding grounds for violent jihadism in Switzerland (e.g., jihadist preachers in mosques); secondly, most Muslims in Switzerland are comparatively well integrated; third, 90 per cent of Swiss Muslims have their roots in the Balkans or Turkey, where Islam is generally interpreted in a tolerant and apolitical fashion; and fourth, neutral Switzerland is much less exposed on the world stage than other countries. (Lorenzo Vidino, Jihadist Radicalization in Switzerland, November 2013, CSS/ETH)

Internationally, Switzerland’s counterterrorism efforts are conducted in the framework of the respective UN strategy and international treaties. Switzerland’s engagement is guided by three principles, the so-called “Three Rs”: Reliable, rights-based, and responsive. First of all, Switzerland guarantees compliance with international standards and agreements – for instance, to prevent terrorism financing in Switzerland. Secondly, in multilateral fora, Switzerland promotes the observance of international law and human rights in global counterterrorism efforts. Third, Switzerland seeks to eliminate the structural drivers of violent extremism through PVE-relevant development, conflict prevention, and peacebuilding efforts. Switzerland supports the Global Community Engagement and Resilience Fund (GCERF). Founded in 2014 and headquartered in Geneva, this public-private partnership fosters local initiatives on the community level around the globe in order to strengthen resilience to violent extremist agendas.

Switzerland is an active participant in the international political debate on CVE/PVE. At the CVE summit in New York in September 2015, Federal Councillor Didier Burkhalter emphasized the importance of a comprehensive and holistic approach to preventing violent extremism that takes into account the spheres of peace and security, development, and human rights. He has announced Switzerland’s willingness to host the first international conference on the implementation of the UN Action Plan on PVE in Geneva in the spring of 2016. Against the backdrop of heated emotions following the Paris attacks on 13 November 2015 and the knee-jerk response of “tough” security measures, Switzerland should reinforce its efforts in international debates to promote open dialog between the advocates of both “soft” and “tough” responses in combating terrorism. This is the only way to maintain a focus on the root causes of violent extremism and on the lessons of the past decade’s CVE debates.

No comments:

Post a Comment