By Lisa Watanabe for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

The this article was originally published by the Center for Security Studies (CSS) as part of the CSS Analysis in Security Policy series in February 2015. The neglect of the Sinai and growth of a security vacuum on the peninsula has transformed Egypt’s backwater into a stronghold of militancy, with implications of not only national, but also regional and global significance. On 10 November 2014, the deteriorating situation in the Sinai was thrust into the spotlight when the most capable and active Salafist jihadi group on the peninsula, Ansar Bayt al-Maqdis (“Supporters of Jerusalem”, ABM), pledged allegiance to the so-called Islamic State (IS) and renamed itself the “Sinai Province”. However, it has really been at least a decade since the alienation of the local population from the central state and the erosion of the latter’s authority in the peninsula began to provide fertile ground for such groups to emerge on the Sinai. The security vacuum created by the fall of the Mubarak regime in 2011 provided a further impulse for the transformation the Sinai into the site of a full-blown insurgency and a haven for jihadi groups, some of which have links to global terrorist networks. The Egyptian military and security services in particular have been targeted by Sinai-based violent Islamist groups since the 2013 coup.

The this article was originally published by the Center for Security Studies (CSS) as part of the CSS Analysis in Security Policy series in February 2015. The neglect of the Sinai and growth of a security vacuum on the peninsula has transformed Egypt’s backwater into a stronghold of militancy, with implications of not only national, but also regional and global significance. On 10 November 2014, the deteriorating situation in the Sinai was thrust into the spotlight when the most capable and active Salafist jihadi group on the peninsula, Ansar Bayt al-Maqdis (“Supporters of Jerusalem”, ABM), pledged allegiance to the so-called Islamic State (IS) and renamed itself the “Sinai Province”. However, it has really been at least a decade since the alienation of the local population from the central state and the erosion of the latter’s authority in the peninsula began to provide fertile ground for such groups to emerge on the Sinai. The security vacuum created by the fall of the Mubarak regime in 2011 provided a further impulse for the transformation the Sinai into the site of a full-blown insurgency and a haven for jihadi groups, some of which have links to global terrorist networks. The Egyptian military and security services in particular have been targeted by Sinai-based violent Islamist groups since the 2013 coup.

However, the Egyptian authorities are not their only target. Several of the Sinai-based groups have launched attacks on Israeli targets and used the tunnel networks connecting the Sinai with the Gaza Strip to their advantage, giving them the capacity to affect the delicate triangle of relations between Egyptian, Israeli, and Gazan authorities. Of additional concern is their potential to target civilian aircrafts, tourist resorts, and ships on the Suez Canal, as well as to engage in kidnapping for ransom. As such, European states, including Switzerland, have an interest in promoting an improved situation in the Sinai.

Palestinians run as smoke rises after a house is blown up during a military operation by Egyptian security forces in Rafah, on the Egyptian side of the border with the Gaza strip (30 October 2014). Image courtesy of Ibraheem Abu Mustafa/Reuters.

Armed Groups on the Sinai

The Sinai Peninsula is home to a range of armed non-state actors, including militant Bedouin and Islamist groups. Lack of access to the area makes it difficult to gain a clear picture of the state of affairs. However, Hamas and other Gaza-based militants are thought to be involved in smuggling goods, weapons, and explosives into Gaza via a network of tunnels originating in northeast Sinai. Salafist jihadi groups that share al-Qaida’s ideology or have recently pledged allegiance to the IS are also believed to be based in this northeast corner of the Sinai. In the coastal areas along the Suez Canal, Islamist militant groups based in mainland Egypt that primarily target the Egyptian authorities are thought to be most active. Little is known about the precise relationship between these groups, though some degree of logistical overlap and cooperation is discernable. Their main sources of revenue come from illicit activities made possible by the Sinai’s well-established smuggling economy and contributions from foreign Islamist militant groups.

The most operationally capable and prolific Salafist jihadi group is “Sinai Province” (formerly ABM), which claims to have been founded in 2012 by Egyptians. The group is al-Qaida-inspired, though no direct organizational link with al-Qaida exists. Its members are mostly local Bedouin, though it recruits from the wider Middle East, including the Syrian battlefield, and North Africa. The group initially carried out attacks on Israeli targets, such as the city of Eilat and the pipeline that transported natural gas through the Sinai to Israel until 2012. However, following the 2013 coup, it declared war on the Egyptian military and security forces. Recent high-profile attacks include the attempted assassination of Interior Minister Mohamed Ibrahim Moustafa in September 2013, the bombing of the security directorate building in Mansoura in the Nile Delta in December 2013, the near simultaneous bombings in Cairo in January 2014, and the downing of an Egyptian military helicopter with a shoulder-fired missile near Sheikh Zuweid in the same month. The group was also responsible for the two biggest attacks since the ouster of Mohammed Morsi, one again in Sheikh Zuweid on 24 October 2014, which left some 30 security personnel dead in a suicide bomb attack, and another involving four incidents in North Sinai on 29 January in which at least 30 people were killed.

The Mujahideen Shura Council in the Environs of Jerusalem (MSC) is another of the more prominent groups. Founded in 2012, MSC is an umbrella group comprising several jihadi groups based in Gaza. It opposes the 1979 Egyptian-Israeli Peace Treaty and has tended to focus on Israeli targets. It has claimed responsibility for a cross-border improvised explosive device attack in June 2012 and for rocket attacks on the Israeli cities of Sderot in March 2013 and Eilat in April and August 2013. The MSC sympathizes with Sinai Province, and it, too, declared its support for the IS in February 2014.

Ansar al-Jihad in the Sinai Peninsula (also known as al-Qaida in the Sinai Peninsula) was founded in 2011, at the same time announcing its intention to “fulfil the oath of Osama bin Laden”. The founder, Ramzi Mahmoud al-Mowafi, who was Osama bin Laden’s physician, broke out of prison in 2011 and by the end of that year had formed Ansar al-Jihad in the Sinai Peninsula, declaring allegiance to al-Qaida’s Ayman al-Zawahiri. The group claimed responsibility for a number of attacks on the gas pipeline that transports natural gas through the Sinai to Jordan and previously to Israel, and an August 2013 attack on the paramilitary Central Security Forces is believed to have been linked to the group.

Another group that has connections not only with al-Qaida leaders, but also with al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and al-Qaida in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), is the Mohammad Jamal Network (MJN), established by Mohammad Jamal Abu Ahmad, a local militant, who was imprisoned during the Mubarak era and released in 2011. Until his arrest in 2012, Mohammad Jamal was the leader of a Nasr City cell in Cairo, believed to be planning attacks inside Egypt. However, he established training camps not only in Egypt, but also in Libya. Some of the attackers of the US embassy in Benghazi, Libya, are reported to have been trained in MJN camps in Libya. The MJN is believed to have received funding from AQAP, and to have recruited for and carried out acts on behalf of AQAP and AQIM, and Mohammad Jamal was believed to have connections with Sinai Province and Islamist extremists in Europe.

The Growth of Militancy

A number of factors have enabled armed Islamist groups to take root and proliferate in the Sinai. The peninsula has never been well integrated with mainland Egypt. Its isolation is not merely physical; the local Bedouin, who make up 70 per cent of the local population (approximately 200 – 300,000), feel a greater affinity with the people who inhabit the lands to their east than with mainland Egyptians. Indeed, some of the Bedouin tribes in the Sinai, such as the Sawarka, Rumeilat, and Tarabeen, also inhabit Gaza and Israel. This, coupled with the Israeli occupation of the Sinai from 1967 until Israel’s complete withdrawal in 1982, has caused the Cairo authorities to view the Sinai Bedouin with suspicion, barring them from employment in the military and security services, and appointing tribal leaders and their People’s Assembly candidates.

Alienation of the Sinai Bedouin from the state has also been generated by the failure of Egyptian governments to respond to their socio-economic needs. Plans to develop the area under Anwar Sadat were largely abandoned under Hosni Mubarak. The development of tourist resorts on the coast of the Gulf of Aqaba, such as Sharm el-Sheikh, tended to be perceived by the Bedouin as benefitting mainland Egyptians and pushing them further into the interior. Development of the northern part of the Sinai through the creation of agribusiness and the gas pipeline to Israel and Jordan was similarly viewed as a means exploiting Bedouin land, to which the Bedouin themselves have no ownership rights.

Largely excluded from the formal economy and unable to cultivate the land legally, the Bedouin developed a parallel economy in the Sinai, smuggling drugs and contraband into Israel through a network of tunnels. The three main tribes straddling the border with Gaza (Sawarka, Rumeilat, and Tarabeen) dominated this illicit trade. To the south of the peninsula, near the Israeli Red Sea resort of Eilat, the Azazmeh and La heiwat tribes have smuggled migrants as well as cigarettes and drugs into Israel. The smuggling trade in the Sinai saw a significant increase following Israel’s withdrawal from Gaza in 2005 and as a consequence of its blockade of Gaza in 2007. By 2009, illicit trade with Gaza was reported to have become the Bedouin’s principal source of income, with trading routes extending as far as Libya and Sudan.

The grievances of the Bedouin, their alienation from the state, and a growing antipathy for Israel rendered them vulnerable to radical Islam. A key juncture in their radicalization appears to have been the crackdown on violent Islamist networks in the Sinai following the 2004 attacks in the tourist resorts of Taba and Nuweiba and the 2005 attack in Sharm el-Sheikh, which led to mass arrests and the imprisonment of local Bedouin with Salafi jihadists. The Israeli pullout of Gaza in 2005 also accelerated radicalization of local Bedouin, as did the 2007 Israeli blockade of Gaza. As the Bedouin became more dependent on smuggling to Gaza, they also fell under the ideological influence of Hamas and Salafist jihadi groups based in Gaza. Another factor was the arrival of a number of previously Gaza-based clerics in the Sinai following the Hamas crackdown on Salafist jihadi groups in the territory.

The fall of Mubarak in 2011 provided local Bedouin with an opportunity to assert their authority in the Sinai. Following confrontations with armed Bedouin, Egyptian security forces abandoned a number of their posts, and weapons and munitions depots in North Sinai were plundered. The collapse of the Libyan regime also increased the quantity and sophistication of weapons being smuggled into the Sinai, some being smuggled into Gaza and others to groups in the Sinai. The lack of central authority presence also enabled some Bedouin imprisoned after the 2004 and 2005 attacks to break out of prison.

The Government’s Response

Since 2011, the central authorities have attempted to restore their presence in the Sinai through both political and military measures. The Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) relaxed restrictions on over-ground crossings, attempted to facilitate intra-Palestinian reconciliation in the hope of re-establishing Fatah’s authority over Gaza, and restarted talks with Bedouin tribal leaders aimed at renegotiating the social contract with the Bedouin. However, negotiations met with resistance from the security forces and were overshadowed by concerns about the country’s overall stability. The SCAF thus launched Operation Eagle I in mid-2011, involving the largest movement of Egyptian troops into the Sinai since the 1973 October War, in an effort to drive Salafist jihadi groups out of North Sinai’s urban centers. The SCAF sought to pressure Hamas into taking further action to sever the link between groups in the Sinai and Gaza by augmenting its control over the Gaza border crossing and restricting fuel supplies to Gaza. Neither measure met with a great deal of success.

During the Mohamed Morsi’s presidency, a mixed approach was again employed. Morsi indicated his willingness to respond to the socio-economic grievances of the Bedouin and initiated talks with the Sinai’s armed groups, mediated by Salafists and former Salafist jihadists. He also supported a relaxing of the overground movement of people and goods into Gaza. Despite these efforts, however, fighting in the Sinai continued, prompting a return to a military response. Operation Eagle II was launched in mid-2012, aimed at protecting the Suez Canal, eliminating armed Islamist groups, and destroying the tunnel network.

Following the 2013 coup, the new authorities in Cairo adopted a more aggressive strategy, leading to mass arrests and hard security measures. In October 2014, the government imposed a curfew and a state-of-emergency, and destroyed homes in the Sinai’s border area with Gaza to create a buffer zone 14 kilometers long and half a kilometer wide. Roughly 800 households were given 48 hours to vacate their homes before the military destroyed them. While 2014 did see a reduction of terrorist attacks, the methods of Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi are reminiscent of Mubarak’s and could add fuel to Bedouin militancy.

The Sinai and Egypt’s Neighbors

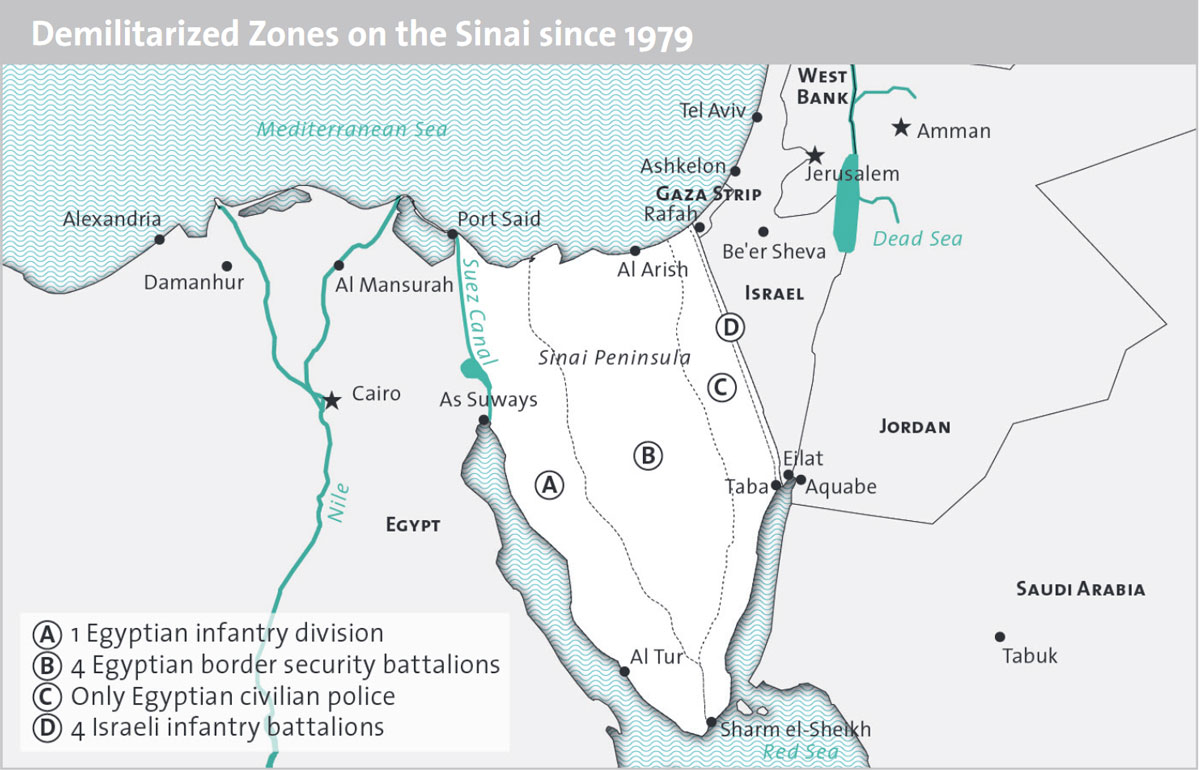

The combustible mix of militancy in the Sinai also has the capacity to affect Egypt’s relations with Israel due to attacks on Israeli targets and the smuggling of weapons into Gaza. The 1979 Egyptian-Israeli Peace Treaty that has underpinned the cold peace between the two countries did not envisage a situation in which non-state actors in the Sinai would jeopardize their respective security. Under the Treaty, the Sinai is divided into zones. In Zone A, close to mainland Egypt, Egypt may station a mechanized infantry division of some 20,000 troops. In Zone B, four border security battalions may be stationed in support of civilian police. In zone C, close to Israeli border, no Egyptian military presence is permitted. The Multinational Force and Observers (MFO), a multinational military force created as an alternative to a United Nations peacekeeping force in 1981, is tasked with monitoring these provisions. The MFO is funded by Egypt, Israel, and the US, and also receives contributions from other countries, including Switzerland. In Zone D, within Israel, Israel may station four infantry battalions.

Despite these restrictions, the treaty does provide mechanisms for ad-hoc changes in the level of Egyptian forces in the Sinai, provided Israel agrees, and such changes have taken place in the past. Since 2011, there was only one instance when Egyptian military forces deployed to Zone C without prior permission, but on that occasion, they withdrew following Israeli alarm. While Israel does not want to see the remilitarization of Zone C become a permanent fixture, Tel Aviv has de-facto accepted the remilitarization of eastern Sinai and is currently relying on the Egyptian military to at least contain the situation in the Sinai. Thus far, Israel has largely refrained from pre-emptive measures inside Egyptian territory, instead passing on intelligence gathered in Gaza to Egypt. The continuation of stable relations, nevertheless, will depend on good faith between the two neighbors.

The situation in the Sinai also has implications for relations between Cairo and Hamas. During the final years of the Mubarak regime, Egypt had expressed growing concern about synergies between Gaza-based militants, Hamas, and the Sinai Bedouin. Nevertheless, once in power in Gaza, Hamas sought to demonstrate its importance for stability and cracked down on Salafist jihadi groups in Gaza, causing some to flee to the Sinai, where they could operate more freely and form ties with Bedouin tribes and Egyptian and foreign Salafist jihadis. Efforts by the authorities in Cairo to sever these connections still pose a challenge to Hamas’ authority in Gaza, however. Destruction of the tunnel economy, for instance, would deny Hamas a taxable source of revenue.

Outlook

No long-term solution to the problem appears to be in sight. The factors that contributed to the insurgency and the creation of a haven for jihadi groups persist. The population remains alienated from the state and economically dependent on illicit activities. In addition, repression of Islamists in Egypt and heavy-handed treatment of Sinai Bedouin are likely to feed the Salafist jihadist narrative and generate support for their cause. Ultimately, development measures that boost the integration of Bedouin into the formal economy and provide alternatives to smuggling are needed. Engaging tribal leaders and including the Bedouin in state structures in the Sinai are also likely to be important in improving relations between the Cairo authorities and the local population, as well as improving the security situation in the peninsula. However, the poor state of Egypt’s public finances and the myriad challenges facing the country as a whole mean that the needs of the Sinai may continue to be neglected, despite the promise to invest in the Sinai following the recent January 2015 attacks. Countries seeking to support Egypt’s transition and stability in the region, including Switzerland, could play a valuable role in supporting local dialog initiatives and to stimulate sustainable development and job creation that benefit the local Bedouin. Support for small-scale agricultural production aimed at niche markets, provision of microcredits, and support for small- and medium-sized enterprises, for example, could all be means of providing legal economic activities to the Bedouin.

No comments:

Post a Comment