By John F. Sullivan

The author James Clavell once wrote that if he were ever put in charge of the U.S. military, he would require all generals to take an annual written and oral exam covering the tenets of Sun Tzu—with those scoring below 95 percent being summarily dismissed.[1] Predictably, the proposal never gained much traction within the Pentagon, but the hypothetical exam raises an interesting question. Would we even be able to agree on a common, testable understanding of the principles inherent in The Art of War? The number of prominent Western military strategists who consistently attribute to Sun Tzu phrases never a part of his work suggests the Chinese sage suffers the same fate as his Prussian counterpart.[2] That is, he is the author of a book “well-known but little read.”[3] As a result, we too readily ascribe to Sun Tzu contemporary views bearing little resemblance to the cultural and historic milieu that ultimately grounds the text. In short, we stray too far from the original document we are attempting to interpret for a modern audience.

Take the almost unquestioned belief that Sun Tzu articulated a surprisingly modern and enlightened ethical stance by directing the enemy writ large be treated humanely during wartime. The U.S. Army Judge Advocate General’s Legal Center publishes the Law of Armed Conflict Deskbook, in which the authors state: “Sun Tzu’s The Art of War set out a number of rules that controlled what soldiers were permitted to do during war, including the treatment and care of captives, and respect for women and children in captured territory.” This view of Sun Tzu's thinking, though, does not reflect the ideas put forth in the actual text. The Art of War may not have proposed wanton destruction for its own sake, but it was also far from an ancient proponent of our modern laws of warfare.

Thoughts on the need to respect women and children in captured territory, for example, are not to be found anywhere within the thirteen chapters of the extant text. A reference to children occurs in a single verse, but only through analogy reflecting how leaders should treat their own soldiers as either infants or beloved sons to inspire ultimate devotion.[4] If treated too leniently, though, Sun Tzu also warns us they will become as useless as spoiled children. A reference to women is made only once, in a suggestion one should act like a “modest maiden” while trying to deceive one’s opponent into believing that you have no intention to invade their territory prior to the moment of launching the attack.[5]

What Sun Tzu does emphasize on multiple occasions, though, is the need to plunder enemy territory to provide food and resources for one’s own army during the course of an invasion. (Sun Tzu recommends only invading another state, admonishing one to never fight a defensive war within one’s own borders). Although the intent was to rely on enemy resources to spare hardship among the populace at home, his writings reflect no concern over how looting and plundering on enemy soil might also cause intense suffering to the noncombatants of the invaded state.

The treatment of captured combatants, however, is briefly mentioned by Sun Tzu and is often used to buttress the argument that he held a surprisingly lenient view of how all prisoners of war should be treated. As mentioned above, though, since Sun Tzu is relying on plundering enemy territory to sustain his own army, it is difficult to see how he would be in a position to also adequately care for a mass influx of prisoners taken while conducting an offensive campaign far from home. Accepting responsibility for these captives would be problematic for a commander relying on speed, maneuver, and deception deep inside enemy territory with sporadic access to the sustenance needed to feed and care for his own troops through pillaging, let alone others.

Despite this, in Chapter 2 of the text ("Waging War”) Sun Tzu mentions that one should “provide for captured soldiers and treat them well.” This statement can be easily misconstrued, however, if taken out of its original context. The character Sun Tzu uses to identify those who should be treated well is zu (卒), which literally means troops or soldiers in the generic sense, indicating neither friend nor foe, captive nor free. Only in the context of the complete verse do we get the sense the soldiers to which he is referring to are actually prisoners of war, but that additional background information is vital to our understanding. The full verse reads:

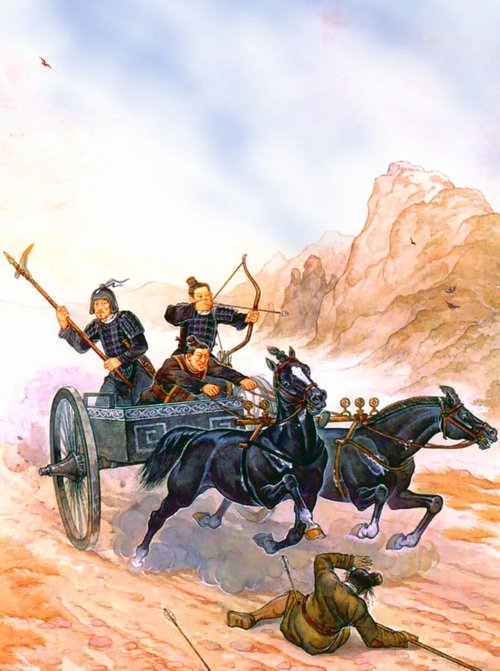

Killing the enemy is a matter of arousing the anger of our men; snatching the enemy's wealth is a matter of dispensing the spoils. Thus, in a chariot battle where more than ten war chariots have been captured, reward those who captured the first one and replace the enemy’s flags and standard with our own. Mix the chariots in with our ranks and send them back into battle; provide for captured soldiers [zu] and treat them well. This is called increasing our own strength in the process of defeating the army.[6]

Placed in its full context, the lenient treatment of enemy soldiers can only be definitively linked to those limited numbers rounded up in what can best be described as a captured chariot incentive program. The question remains, why might Sun Tzu have a vested interest in treating the captured charioteers humanely? The answer may lie in how the armies of Sun Tzu were trained and organized and the importance of chariots to the strength of that army.

Qin Dynasty war chariot in battle during the Warring States, Ancient China (Pinterest)

Chariots were by far the most powerful component within the armies of the early Warring States period (475-221 BCE). In the T’ai Kung’s Six Secret Teachings, which along with The Art of War makes up the canonical Seven Military Classics of Ancient China, King Wu asks his military advisor, “When chariots and infantry engage in battle, one chariot is equal to how many infantrymen?” The advisor replies, “Ten chariots can defeat one thousand men.”[7] Thus, the ten captured chariots Sun Tzu covets would significantly enhance his overall combat capability provided that they could be successfully incorporated into his own order of battle.

Maneuvering a chariot in battle was also a difficult skill to master, though, requiring years of training by those wealthy enough to maintain their own steeds, stables, and fields during peacetime and the spare time needed to practice equestrian arts. Since Sun Tzu would be invading with all available chariots and crews from his own home territory, he would not have any spare trained personnel available to effectively man these captured vehicles in battle. To have any chance of using these additional potent weapons against the enemy, he would first need to convince the captured charioteers to fight for him.

That he would prefer to use a carrot as opposed to a stick when compelling these captive chariot crews to fight against their former comrades is not without rationale. The Zuozhuan (a work recounting the historical events directly preceding the Warring States era and most likely compiled during the same period as The Art of War) relays the experience of Hua Yuan, the commander of the Song forces that were about to go to war with the state of Zheng in 607 BCE:

On the eve of battle, Hua Yuan had slaughtered a sheep to feed his men, but his chariot driver Yang Zhen had been denied his portion. When it was time for battle, Yang said, “With yesterday’s mutton, you were in charge, but in today’s affair, I am in charge.” He drove the chariot into the ranks of the Zheng army, hence Song’s defeat.[8]

A disgruntled or mistreated charioteer, much like the modern strategic corporal, could have an enormous impact on the success or failure of an operation, and forcing them into service at the tip of a spear would ultimately be counterproductive. That Sun Tzu recommends treating any enemy humanely, especially during the period of savage and brutal internecine warfare that characterized the Warring States era is notable, but what is not clear is whether this largesse would extend to another prisoner who could not immediately benefit Sun Tzu’s drive for victory over the enemy. The fact that subsequent Chinese military texts heavily influenced by his philosophy—including Sun Bin’s Art of War which was allegedly written by Sun Tzu’s progeny—fail to mention the lenient treatment of captive soldiers suggests this idea was never meant to be a significant part of the overall military theory.[9] That we raise this example up to the level of the Geneva Conventions speaks more to our own modern sensibilities than an accurate reflection of the mores practiced by the military class in ancient China.[10]

In an interview with the members of the Denma Translation Group—which publishes a popular version of The Art of War—the authors state that the language of Sun Tzu “can apply equally to the mother putting her son to bed and to a platoon commander resisting his superior officer’s disastrous order to fight the wrong battle.” If so, one wonders what the child thinks when his mother tells him that when using incendiary attacks to burn enemy troops alive in their camp one should follow that up with an armed assault to inflict maximum damage (weather conditions permitting). Conversely, will the lieutenant contemplating dereliction of duty find solace in Sun Tzu’s insistence that if a spy divulges his information prematurely, not only the spy but everyone to whom he possibly could have revealed the information should be immediately put to death?

...SHOULD WE REALLY BE SHOCKED TO FIND WARFARE GOING ON IN THE ART OF WAR?

Despite the prevailing conventional wisdom, the text was never intended to be used as a guidebook for raising children nor as a manual for moral resistance. It is ultimately a book about war and killing, not generic conflict resolution where the threat of violence is far removed from the interaction. Decades of evolving Sun Tzu into a pop-psychological guide to managing business, relationships and general competitive endeavors has unmoored the text from its proper sanguinary roots. Paraphrasing Captain Renault in Casablanca, should we really be shocked to find warfare going on in The Art of War?

John Sullivan is a former U.S. Army China Foreign Area Officer who served assignments in Taipei, Beijing, and Washington, DC. He is currently a JD candidate at the University of Hawaii’s William S. Richardson School of Law.

This article appeared originally at Strategy Bridge.

No comments:

Post a Comment