By Rainer L Glatz and Martin Zapfe

According to Rainer L Glatz and Martin Zapfe, NATO’s Framework Nations Concept (FNC) currently serves as a practical guideline for defense cooperation within the Alliance. But what does the FNC, with its emphasis on national sovereignty, actually mean for defense cooperation? To help provide an answer, Glatz and Zapfe here review 1) the three different FNC approaches that exist within NATO; 2) the opportunities and limits of the FNC; and 3) how the FNC’s approach to cooperation might be especially attractive to states that are not NATO members.

According to Rainer L Glatz and Martin Zapfe, NATO’s Framework Nations Concept (FNC) currently serves as a practical guideline for defense cooperation within the Alliance. But what does the FNC, with its emphasis on national sovereignty, actually mean for defense cooperation? To help provide an answer, Glatz and Zapfe here review 1) the three different FNC approaches that exist within NATO; 2) the opportunities and limits of the FNC; and 3) how the FNC’s approach to cooperation might be especially attractive to states that are not NATO members.

Within NATO, the so-called “Framework Nations Concept” is currently one of the driving paradigms of multinational defense cooperation. All nations retain full sovereignty, and no “European army” is in sight. This opens the concept to non-member states.

Within NATO, the Framework Nations Concept (FNC) currently serves as a pragmatic guideline for defense cooperation. Until recently, programs such as “Smart Defence” (NATO) or “Pooling & Sharing” (EU) appeared without alternative. Given the huge budget pressure created by the global financial crisis, NATO and EU states decided either to pool their resources centrally or to make joint use of them.

These models remain relevant, but they are not sufficient. First of all, it is unrealistic to expect “more for less” and to hope that cooperation alone will be enough to make up for significant spending cuts in the national budgets. Secondly, these programs are primarily aimed at making basic operations more efficient, while effectiveness in combat has been a secondary consideration. This was acceptable at a time when scenarios for collective defense were considered unthinkable – a basic assumption of European security policy that does not appear to be valid after Russia’s annexation of Crimea. Thus, the primary aim now is not to spend less on defense, but to make better use of the available means and create more effective forces.

This is where the security-policy and economic rationales of cooperation under the FNC come into play. In future, only few states will still have the ability to maintain armed forces for all scenarios. It is only through collaboration that they can even hope to come close to fielding the required number of combat-ready divisions and squadrons; and only by continuing to harmonize procurement of defense equipment can the exorbitant unit prices and maintenance costs be brought down to more tolerable levels.

This is where the security-policy and economic rationales of cooperation under the FNC come into play. In future, only few states will still have the ability to maintain armed forces for all scenarios. It is only through collaboration that they can even hope to come close to fielding the required number of combat-ready divisions and squadrons; and only by continuing to harmonize procurement of defense equipment can the exorbitant unit prices and maintenance costs be brought down to more tolerable levels.

A new architecture for NATO? Opening of NATO Headquarters in Brussels, 25 Mai 2017. Jonathan Ernst / Reuters

At the same time, centralization is not constrained by national sovereignty only. While most NATO states share fundamental interests, they also have different priorities in accordance with varying national threat perceptions. While the Baltic states and Poland look eastwards and fear the Russia of President Vladimir Putin, Italy and the states on NATO’s southern flank look to the south and see instability and uncontrolled migration. There currently is no common threat perception shared by all NATO states. Therefore, it appears that future cooperation within NATO will have strike a delicate balance: It will have to be coordinated centrally yet organized and implemented in a decentralized manner. The FNC has the potential to strike such a balance successfully.

Pragmatic Cooperation

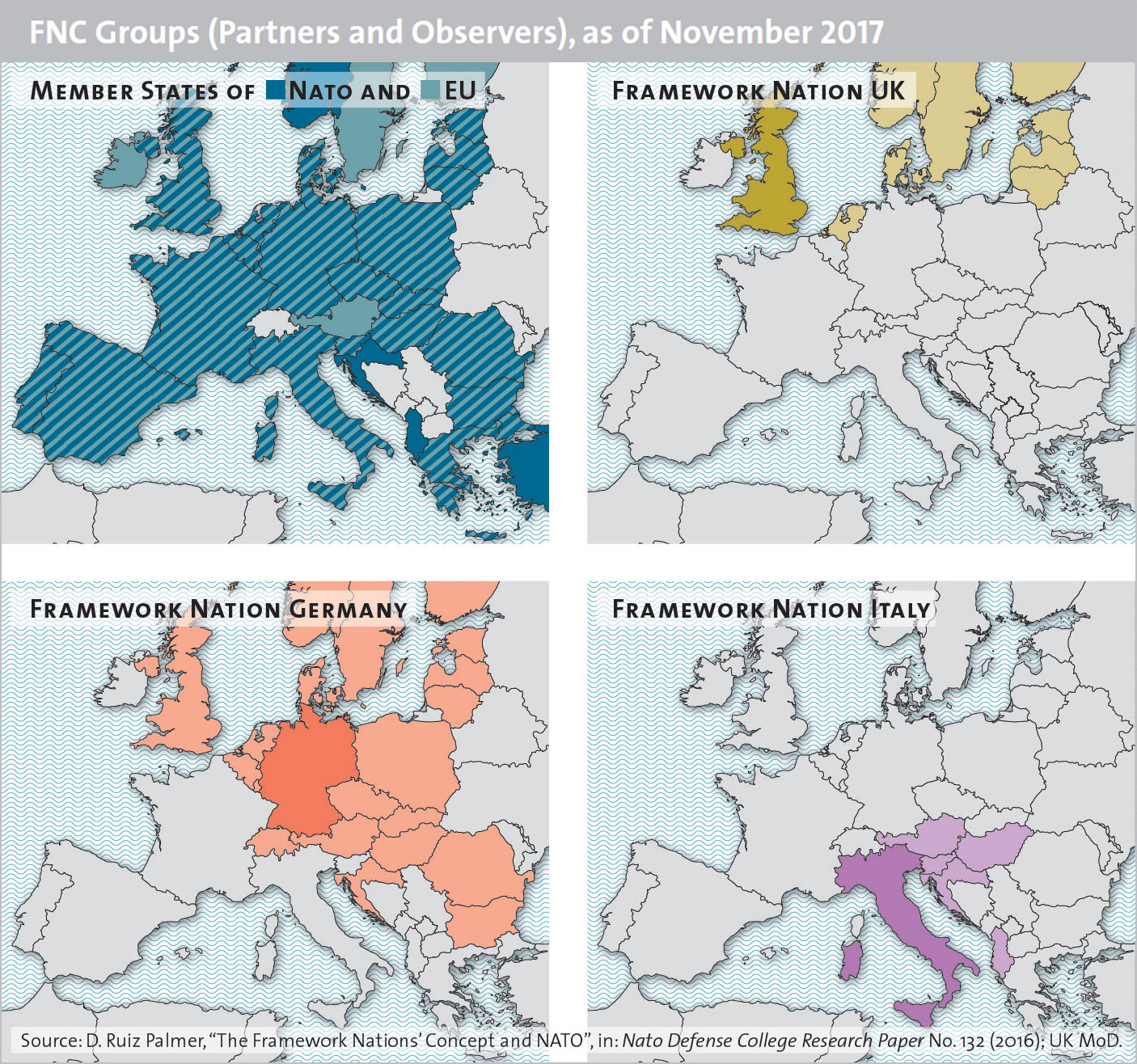

The FNC as it exists today materialized in 2013 from a German proposal and was adopted by NATO in 2014. Nevertheless, it continues to be driven, funded, and designed by the individual nations. The FNC reflects a pragmatic approach to cooperation: States cooperate voluntarily in a highly agile format and while retaining their full sovereignty wherever they choose to do so – and in a best-case scenario, they do so with NATO coordination and while adding the greatest possible value for the alliance. Public debate on the matter is complicated by a certain ambiguity in terminology as there are three different FNC approaches within NATO, which are grouped around different framework nations and differ considerably in terms of aims, methods, and structure.

Germany: Armed Forces Development

Today, the German FNC group rests on two pillars, which are partly interdependent. From its inception, the group has concentrated on the coordinated development of capabilities in so-called “capability clusters”. Since 2015, there has been an additional focus on building up larger multinational military formations. To date, 19 other nations have joined Germany’s FNC group; seven of these states have already committed forces of their own for the second area of activity, while others are still considering doing so. Formally, both pillars of the FNC are of equal importance; in the long term, however, the development of capabilities and structures for NATO’s pool of forces through “larger formations” is the far more important of these tasks.

The first pillar of the FNC is designed to help participating states close capability gaps. The strategic focus of the capability clusters is in line with the capability shortfalls identified and prioritized by NATO; however, it is the FNC states, coordinated by Germany, that determine further steps to fill these gaps. Today, the German FNC incorporates 16 clusters, each of which relates to one or more capability goals – e.g., anti-submarine warfare. The FNC nations are free to choose in which clusters they wish to participate; further clusters are currently being formed.

The second pillar of the German FNC is considerably more important. Some observers have depicted it as the core of a “European army” – possibly even dominated by Berlin. It is in fact primarily an ambitious plan for structured and collaborative force planning under German leadership: On the one hand, it is hoped that close cooperation between the FNC states’ units, with the Bundeswehr as their core, will improve the fundamental interoperability of the forces involved and harmonize capability development. On the other hand, with a view to potential scenarios – including, but not limited to, in the eastern part of the alliance – the cooperation is to lay the groundwork for combat effective multinational divisions built around Germany as the framework nation.

Germany’s role in these formations and structures – whether on land, in the air, or at sea – would be significant. By 2032, and thus in parallel to Germany’s national plans, the FNC force pool is to provide three multinational mechanized divisions, each capable of commanding up to five armoured brigades. As of now, two of these divisions would be formed around German divisional headquarters. A Multinational Air Group (MAG), to be enabled through the FNC, already fundamentally shapes the German Air Force’s planning. The MAG would rely on German capabilities to an extent exceeding 75 per cent. To put it differently: The German Air Force has effectively offered its entire capability spectrum to the MAG.

In any scenario of collective defense Germany could thus well become the indispensable framework nation for most of its smaller FNC partners, and NATO as a whole. Nevertheless, for the foreseeable future, all states would retain their respective national political freedom of action to equip and deploy their armed forces. Within the FNC, all states are invited to “plug in” parts of their forces to German structures, and yet they retain the explicit right to “plug out” at any point in time. This in itself should make it clear that concerns about a “German-dominated European Army” only serve to obscure the many relevant implications of the FNC. At the same time, however, this lack of legally binding cooperation in times of crisis should also caution against overblown expectations of efficiency gains through the FNC.

The UK: Joint Expeditionary Force

The UK-led group has chosen a different approach to cooperation within the FNC. It largely omits integrative elements of force planning and development, while concentrating on a model that is no less ambitious: The creation of a framework for rapid multinational intervention forces in high-intensity operations. This is taking place in the framework of the so-called “Joint Expeditionary Force” (JEF) of the British Armed Forces.

The JEF was originally conceived in 2012 as a purely national formation to serve as the main UK contribution to unilateral operations or those involving allies. Later, the JEF concept was “internationalized” to offer a connection where Britain’s traditional partners could attach their own forces – however, it is intended that the JEF’s core should still be deployable in purely national or ad-hoc coalitions. In September 2014, the defense ministers of the UK, Denmark, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Norway, and the Netherlands signed a memorandum of understanding establishing the JEF as a multinational rapid intervention force. It is anticipated that, following a certification exercise, the JEF will report full operational capability in the summer of 2018. At the core of the JEF will be the British Joint Forces Command with liaison officers from JEF partners continuously present.

The participating nations in the JEF give a clear indication of its regional focus on cooperation in the north and east of the alliance. This became even clearer in June 2017, when Finland and Sweden decided to join the JEF. Though neither of these are NATO states, they are both deeply concerned over Russia’s behavior and interested in developing deeper ties with the alliance – and also, amid discussions over London’s exit from the EU, deeper ties with the UK.

Despite the ambitious announcements, the JEF is not a standing formation within the FNC, but an open cooperation framework with a view to create a pool of rapidly available forces. Each nation supplies contingents of forces on a case-by-case basis – or not. In peacetime, the JEF is to enhance the interoperability of national armed forces through regular exercises, with the various nations remaining responsible for mid-to long-term force planning. The JEF reflects a pragmatic approach to cooperation that avoids excessive “institutional ballast” and seems to be much less closely tied to alliance processes than the German FNC. It is a consciously exclusive model under British leadership that avoids the inclusive, capability-oriented approach of Germany.

Italy – Stabilization Operations

The third FNC group, under Italian leadership, concentrates on two aspects: Firstly, on the development of capabilities for stabilization operations and support for local security forces, and secondly, on establishing rapidly deployable multinational command structures. Like Rome itself, therefore, the Italian FNC group looks southwards towards North Africa and the Middle East. In 2015, a letter of intent was signed by Italy, Albania, Croatia, Hungary, and Slovenia, as well as non-NATO member Austria. Overall, however, it appears that this cooperation format is considerably less ambitious and tangible than that of the other two FNC groups.

Opportunities and Limits

What all FNC groups share in common is the pragmatic and decentralized approach to multilateral cooperation. NATO’s 2014 approval of the FNC has the potential to link up all three cooperation models with alliance processes in order to create synergies within NATO in a top-down approach. For instance, the clusters of the German FNC are designed to close capability gaps identified by NATO, and it is anticipated that the units established on the basis of the German “larger formations” or the British JEF can also be made available to the alliance. However, fundamentally, cooperation is a matter for the states and their varying decisionmaking fora and processes to decide in a bottom-up approach. The FNC acknowledges that sovereign states remain the central actors of European defense cooperation within NATO. This strategic pragmatism provides room of maneuver yet concurrently sets limits.

Primarily, the active role of states means a tremendous increase of flexibility. Instead of an all-too-often symbolic “pooling” of resources, cooperation within the FNC could directly benefit the national armed forces – and thus, indirectly, the alliance. Even though NATO plays an important role in the planning and development of armed forces, the states are understandably loath to hand over this responsibility. This pragmatic approach also skirts sensitive issues such as collectively financing allied capabilities, while avoiding any perception of curtailing the freedom of action of the national parliaments, such as might arise if soldiers are assigned to NATO’s integrated command structure.

However, this flexibility also has its disadvantages. As a concept of the states, the FNC stands or falls with these states’ resolve. In the absence of decisive leadership by the respective framework nation, the flexibility of the FNC risks turning from a strength into a weakness, as the alliance lacks a central coordinating agency. Moreover, while the German and British FNCs rightly focus on a force pool based on national armies, this does not necessarily offer an immediate solution to the challenge of rapidly generating multinational units in the event of a crisis – even though cooperation through the FNC naturally aims at accelerating any future force generation.

Finally, the underlying trends towards closely cooperating groups of states have consequences of their own. It cannot be overlooked that the three FNCs are manifestations of a rough geographic orientation. This may be helpful for operationalizing NATO’s “360-degree” approach, i.e., the attempt to take all challenges on the alliance periphery equally seriously. Additionally, such a “regionalization” may also ease force planning. At the same time, however, any regionalization and specialization is a threat to the interoperability and especially the political cohesion of the alliance. It is possible that the alliance will witness “multi-speed cooperation” or even “coalitions of the willing”. It is on the member states and allied institutions in Brussels to prevent or at least to moderate such developments.

Implications for Non-NATO States

While there are considerable differences in the nature of cooperation – depending on the FNC group and the specific field of cooperation – the FNC’s “philosophy of cooperation” appears highly attractive especially for states that are not members of NATO. The bottom line seems to reveal a key advantage of the FNC: It affords at least some insights into central processes of NATO’s force planning and development – and thus, potentially, easier linkup during crises or missions – without having to become an alliance member or entering into politically sensitive ties with “Brussels”.

Within the British FNC, improving interoperability within a potentially large operational formation appears crucial even for states not part of NATO: In June 2017, Finland and Sweden joined the JEF. In addition to launching joint exercises to improve interoperability, it is clear that the main motivation lay in preparing for major crises in the region. In principle, all military scenarios for conflict in the Baltic would affect or involve Finland and Sweden. In recent years, both states have grown increasingly concerned over Russia’s aggressive behavior and sought to move closer to the alliance. Should the JEF be activated in a crisis, Sweden and Finland could decide to place national forces under the command of the JEF, thus participating in an operation either under NATO or in an ad-hoc framework – all without giving up their non-aligned status.

Regarding the German FNC, the focus on force planning and development shapes the expectations of neutral and non-aligned states. Due to political concerns over their status as neutrals, Switzerland and Austria have so far remained visibly aloof from the German FNC’s “larger formations.” However, the guaranteed “opt-out” suggests that there might not be insurmountable legal hurdles to do so. Nevertheless, the main attraction is the prospect of developing capabilities within the FNC clusters, which has the benefit of being less politically sensitive. Thus, Switzerland has indicated to the German Ministry of Defense its interest in participating in the clusters on “Mission Networks” and “enhanced Host Nation Support”; Austria also takes part, inter alia, part in the cluster on “Mission Networks” and on the development of counter-NBC capabilities. The common denominator of these cooperation formats and topics is the achievement and sustainment of interoperability – mainly, but not exclusively, with a view to joint peace support operations, as in the case of KFOR in Kosovo. Furthermore, the FNC as a concept supported by the nations may also potentially open up opportunities for military contacts without excessive political and institutional “ballast” – for instance, in the context of Turkey’s ongoing efforts to impede cooperation between Austria and the alliance.

Last but not least, all this also underscores that a differentiation between “neutrality” and “non-aligned status” still goes beyond mere semantics. With its “Common Security and Defence Policy”, the EU is already a long-established military actor, and recent advances in the framework of Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) may even reinforce that characteristic. In principle, therefore, multinational defense cooperation with EU partners is less problematic for partner states such as Sweden, Finland, and Austria than for Switzerland, for example, even if it takes place under the aegis of NATO – as in the case of the FNC.

No comments:

Post a Comment