By Sabina Stein for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

Interreligious tensions between Buddhist majorities and Muslim minorities in Myanmar, Sri Lanka and Thailand remain high. So how should domestic and international actors respond to further peace? In this still topical piece, Sabina Stein suggests that efforts that just focus on strengthening the rule of law and security in the region will not be enough. Indeed, she suggests a more fruitful approach might lie in greater engagement with Buddhist nationalism to understand its concerns and address its fears.

Interreligious tensions between Buddhist majorities and Muslim minorities in Myanmar, Sri Lanka and Thailand remain high. So how should domestic and international actors respond to further peace? In this still topical piece, Sabina Stein suggests that efforts that just focus on strengthening the rule of law and security in the region will not be enough. Indeed, she suggests a more fruitful approach might lie in greater engagement with Buddhist nationalism to understand its concerns and address its fears.

The this article was originally published by the Center for Security Studies (CSS) as part of the CSS Analysis in Security Policy series in February 2014.

Growing tensions in Myanmar, Sri Lanka, and Thailand between Buddhist majorities and Muslim minorities pose a challenge to peace and security both within these countries and in the wider region. Enforcing the rule of law will not be enough. A deeper understanding of Buddhist nationalist discourses and the grievances that underpin them is vital for improving interreligious coexistence in the region.

In 2007, thousands of Buddhist monks descended onto the streets of Myanmar to protest peacefully against the military regime ruling the country at the time. The “Saffron Revolution” – as the events came to be known, owing to the coloured robes of Myanmar’s spiritual leaders – saw monks fall before the bullets of Myanmar’s all-powerful army. The images coming out of Myanmar today are different. Across the country, monks have been leading demonstrations in defence of Buddhism that have been reported as being directed against the country’s minority Muslim communities.

Interreligious tensions also grew elsewhere in the region. In Sri Lanka, monk-led groups such as Bodu Bala Sena (BBS, Sinhalese for Buddhist Power Force) have undertaken similar campaigns. There have been demonstrations against the construction of mosques and churches as well as halal certification. In Thailand’s south, where the government is engaged in a century-old struggle with Malay Muslim insurgents, monks have become caught up in the conflict. The military has moved into some temples, and rumours are circulating of so-called “military monks”.

A mosque stands in ruins in the central Burmese town of Meikhtila where clashes between Buddhists and Muslims left 40 dead in March 2013. Soe Zeya Tun / Reuters

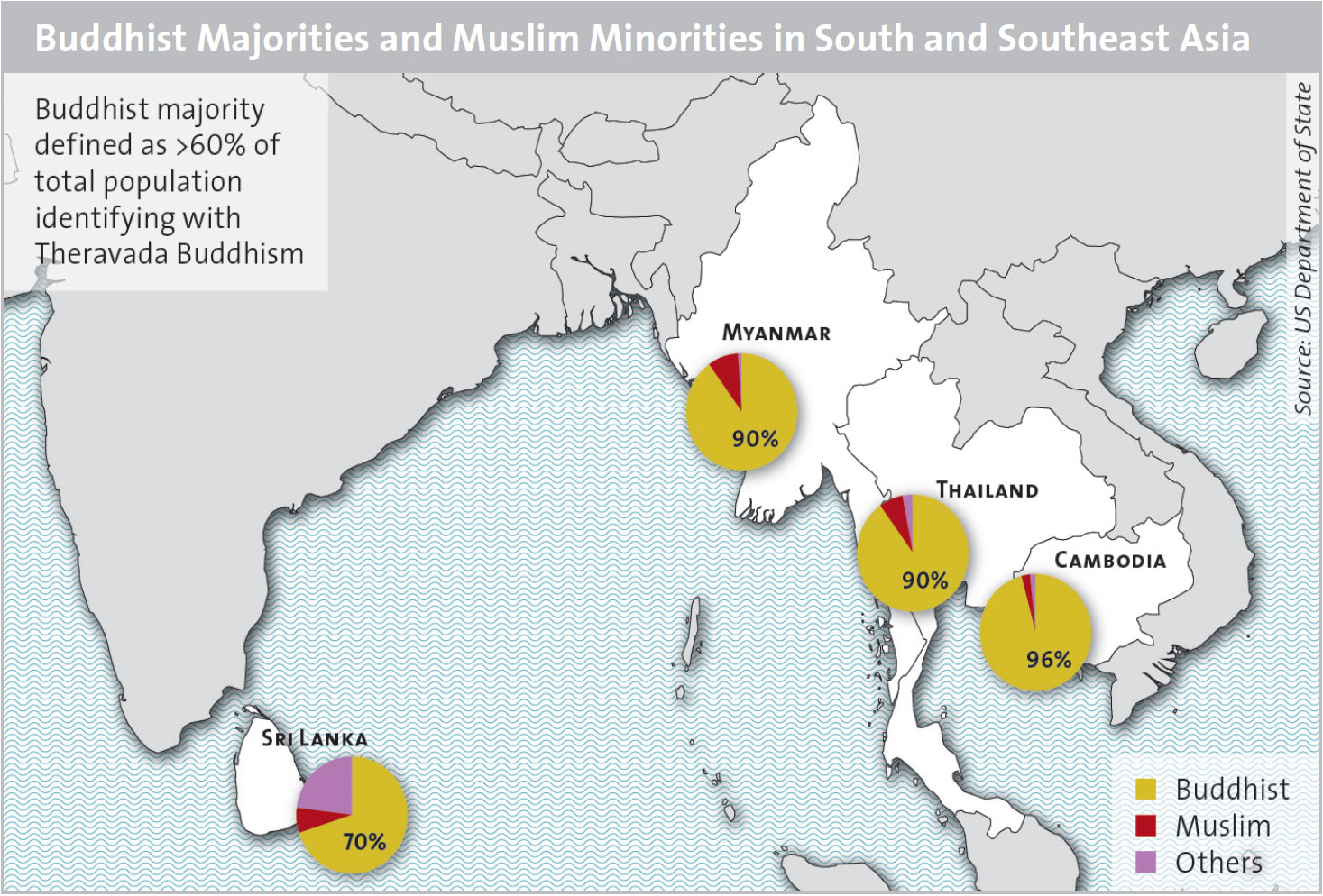

These developments appear to contradict Buddhism’s First Precept, which prohibits the killing of any living being. They also seem to indicate a growing rift between Buddhist and Muslim communities in the world’s most populous Theravada Buddhist- majority countries (see box on next page). Making sense of such developments requires an appreciation of Buddhism’s historical role in legitimising political authority in Theravada Buddhist societies. It also demands an understanding of Buddhist nationalist discourses, which claim that the state belongs to a majority nation – be it Burman, Sinhalese, or Thai – and that this nation is inherently Buddhist. Only if the driving force behind these discourses is understood can the challenge of growing interreligious tensions in South and Southeast Asia be constructively addressed.

Defending Religion and Nation

Prior to European colonial consolidation in South and Southeast Asia in the second half of the 19th century, Theravada Buddhism served as the organising principle of pre-modern states in parts of Thailand, Myanmar, and Sri Lanka. In all three contexts, monarchic states drew their legitimacy by basing their rule on the Dhamma, the Buddha’s teachings, and the support of the Buddhist monkhood. Monarchs thus had an interest in materially and politically supporting the monkhood and took on the role of defenders and promoters of Buddhism. Threats to Buddhism were threats to the state, and threats to the state were threats to Buddhism.

Theravada Buddhism

Buddhism encompasses several traditions that are based on the teachings of Gautama Buddha. Theravada Buddhism is the older of the two major traditions, with the word “Theravada” believed to mean “Teaching of the elders”. Its origins closely associated with Sri Lankan history, Theravada Buddhism is also known as Southern Buddhism. Its 150 million adherents mostly live in Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Cambodia, Laos, and Thailand. Mahayana Buddhism, the second and larger of the major traditions, is practiced predominantly in East Asia in places such as China, Japan, Korea, and Tibet.

European colonialism broke with centuries of Buddhist kingship in Sri Lanka and Myanmar, a rupture that transformed the political role of the Sinhalese and Burman monkhood. With the traditional defender of Buddhism gone and the state no longer supporting the monkhood, sections of the monkhood took it upon themselves to defend Buddhism against foreign rule. This led to the increasing political engagement of some monks in Myanmar and Sri Lanka, actors who would lead the early resistance against colonialism at the turn of the 20th century.

Modern notions of nationalism brought in by Western education also had transformative effects. The historical role of Buddhism in legitimating state authority and the integrative role that Buddhism had played in pre-colonial Burman and Sinhalese societies as purveyor of culture, language, law, and education, made Buddhism a primary ingredient of modern nationalist self-conceptions. This was true among both monastic and lay nationalists. Unlike Myanmar and Sri Lanka, Thailand – then the Kingdom of Siam – was never colonised. Traditional institutions remained in place, and the monkhood had no need to replace the state as defender of Buddhism. Nevertheless, colonial encroachment in the region did challenge the religious legitimation of the kingdom. To secure sovereignty in an expanding system of nation-states, ruling elites saw a need to construct a modern “Thai” nation. This nation was also in great part built on a Buddhist identity.

The emergence of modern Buddhist nationalisms expanded the traditional relation between state and Buddhism to include a third, potent element: the nation. Threats to the state, to the religion, and to the nation were now all interrelated. With the end of colonialism, sections of the monkhood stayed true to their mission to defend Buddhism against new threats, be these Communism or non-Buddhist elements within the body politic. This was especially true in Sri Lanka and Myanmar, where the traditional monarchy was not restored. Here, the monkhood played an assertive and independent role in defending nation and religion. This included exerting pressure upon the newly independent states to promote and support Buddhism, not least by adopting it as state religion. Politically active monks also rejected extending religious minority rights to non-Buddhist minorities. Such activism led to state policies that have been criticised for being exclusionary and discriminatory against religious minorities. The identification of the state with Buddhism also reinforced the political, economic, military, and cultural dominance of the Burman and Sinhala ethnic majorities in both post-colonial Myanmar and Sri Lanka. The same was true in Thailand, although here, the role of the monkhood was less prominent. Nevertheless, Buddhism helped strengthen state sovereignty, including in territories inhabited by non-Buddhist groups such as the hill tribes in northern Thailand.

In all three countries, the strong link made by majorities between Buddhism and the “nation-state” has been suggested to have contributed to the emergence of separatist conflict in southern Thailand, north and north-eastern Sri Lanka, and several frontier regions of Myanmar. Communal violence had also by then become a frequent occurrence in Sri Lanka and Myanmar, predominantly involving Hindu Tamils in Sri Lanka and Indian Muslims in Myanmar. Herein lay the roots of much of the interreligious tensions unfolding in the region today.

Present Tensions

Relations between Buddhists and religious minorities in Thailand are generally good. Nevertheless, the country’s three southernmost provinces have suffered from over a century of conflict between the central state and a Malay Muslim minority that constitutes a majority locally. Following the official incorporation of territories claimed by the Sultanate of Pattani in 1909, Bangkok sought to consolidate its sovereignty over the territories by promoting a strong Buddhist Thai presence and identity in the region. Malay Muslims have responded with non-violent and violent resistance.

A new cycle of violence began in 2004, with Malay insurgents increasingly targeting Thai Buddhist civilians. Teachers and monks, both symbols of the Thai state, have been targeted. The killing of monks has worsened intercommunal distrust and reinforced the perception of the conflict as a religious one. It has also contributed to some southern Thai monks becoming more assertive in defending Buddhism and the Thai nation. Some monks have been accused of propagating anti-Muslim discourses and spreading fear among local Buddhists of Muslim plans for religious cleansing of the territories. Military presence in Buddhist temples and security escorts for monks have also strengthened the perception among Malay Muslims that the state is only interested in protecting the Buddhist population.

In Sri Lanka, some political Buddhist organisations have a history of confrontation with minorities in the country. Many monks opposed granting a degree of territorial and cultural autonomy to the minority Hindu Tamils during the country’s decades- long civil war. Their opposition was reinforced following attacks by the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam on Buddhist holy sites in the 1980s and 90s. Recently, tensions have developed between political Buddhist organisations and the country’s Muslim and Christian minorities. Although there has been violence against Christians, much of these organisations’ recent discourse has concerned the Muslim minority, comprising circa 7 per cent of the total population. This may seem puzzling, given that Sri Lanka’s Muslims are generally characterised as a small, well-integrated, and scattered minority. With the exception of the 1915 Sinhalese-Muslim riots, Muslims have maintained generally peaceful relations with the Sinhalese majority.

Today, however, organisations such as the BBS and Jathika Hela Urumaya (JHU), a partner in the ruling coalition, allege that Muslims are a threat to Buddhism in Sri Lanka. Led by monks, the BBS has held rallies calling for the boycott of Muslim businesses and has raised alarm over the size of Muslim families. In March 2013, the group was successful in having Halal certification of domestic meat products banned. Since 2012, there have also been increasing attacks on mosques and Muslim- owned businesses. There are claims that the BBS has high-level government support, including that of powerful Defence Secretary Gotabaya Rajapaksa, the brother of President Mahinda Rajapaksa, who in March 2013 attended the opening ceremony of a BBS teaching academy. Levels of anti-Muslim violence in Sri Lanka do not compare to those of Myanmar. In the context of rapid political and economic transformations, violence broke out in 2012 in Rakhine State between Buddhist Rakhine and Muslim Rohingya. The Rohingya are a stateless minority considered by the central government and the local Rakhine majority to be illegal immigrants. These tensions, which left approximately 200 dead and 140’000 displaced, were seen as being interethnic rather than interreligious. Since then, violence involving Buddhists and diverse Muslim communities has spread across the country.

According to reports, the 969 movement led by Burman monk Ashin Wirathu has been raising alarm over purported Muslim plans to take over the country and has led successful campaigns to boycott Muslim businesses. In 2012, it organised large-scale protests against plans by the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) to open an office in Yangon and against the visit of an OIC delegation to Myanmar. The position of the government remains ambiguous and has been criticized internationally for a weak response to the tensions. With general elections scheduled for 2015, political elites’ margin of maneuver may be limited.

The Fall of Nalanda

Common to the on-going interreligious tensions in all three countries is the perception of Muslim communities as a threat. Such dynamics are giving rise to common regional discourses that portray Islam as an expansionist force in Buddhist lands. These discourses resonate with historical grievances stemming back to the 12th century, when Islam began making significant inroads in South and Southeast Asia. The 1193 sack of the ancient Buddhist learning centre of Nalanda (today in the Indian state of Bihar) by Turkic armies is kept alive in the collective memory of those who feel today’s Muslims represent a similar threat. The assumed retreat of Buddhism in the face of invading religions – Islam in particular – helped develop among certain segments of the South and Southeast Asian Buddhist community a sense of being a minority in the wider region. This perception was exacerbated by European colonialism, especially in Myanmar and Sri Lanka. In British Burma, moreover, colonial policies led to a high influx of Indian Muslims, who eventually came to dominate certain sectors of the local economy.

All of these latter factors help to explain why many Buddhists, though they constitute comfortable majorities in their respective states, share a sense that their nations must be unified and that their religion is under threat. This has been most pronounced in Sri Lanka, often described by Sinhalese nationalists as the last stronghold or “teardrop” of Buddhism in the Indian subcontinent.

Rumours of Islamic conspiracies to take over the country – be it through marriage to Buddhist women or through rapid population growth – resonate with deep-rooted fears. In this context, Burmese monks’ recent proposals to pass a law curtailing interfaith marriage and attempts to limit the size of Rohingya families in Rakhine State become easier to understand. Anti-Muslim discourses also find fertile ground in communities where Muslims are perceived to have or indeed have achieved a certain level of economic success. In the Burmese town of Meiktila, for example, where violence broke out in March 2013, Muslims reportedly own 75 per cent of jewellery shops. Meanwhile, in southern Thailand, the Buddhist community is a clear demographic minority that has borne the brunt of insurgent violence.

The violent dynamics in all three countries influence and reinforce each other. Leaflets distributed by the BBS in Sri Lanka, for example, decry Muslim violence against Buddhists and Buddhist holy sites in in Myanmar, Thailand, and Bangladesh, where Buddhists in the Chittagong Hill Tracts have been victims of violent attacks. The Sri Lankan government’s decision to censor the July 2013 issue of Time magazine because of its cover story on Myanmar, “The Face of Buddhist Terror”, further illustrates the growing interrelation of Buddhist nationalist discourses in different countries. Sri Lankan monkhood, perceived as the purest in the Theravada Buddhist world, plays a particularly important role in the legitimation and reinforcement of such discourses.

Switzerland’s Support for Religious Coexistence in the Region

Between 2006 and 2011, the Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs (FDFA) ran the “Sri Lanka Dialogue Project” within its “Religion, Politics, Conflict” desk. The project engaged senior members of the Sri Lankan monkhood in a dialogue, exploring their hopes and fears for the future of their country. The project also sought to bring Buddhist leaders together with members of the Muslim and Tamil communities to discuss possible solutions to conflict on the island. The project was suspended in 2011. As part of its on-going peace promotion efforts in Sri Lanka, Thailand, and Myanmar, Switzerland continues to explore ways of addressing the role of religion in these contexts.

Buddhist fears of Islamic encroachment have been compounded by international discourses on the “War on Terror” that frame Muslims as threatening extremists. The Taliban’s 2001 destruction of the Buddhas of Bamiyan in Afghanistan stoked regional fears of a Muslim challenge to Buddhism. Commentators have also pointed to the Thai government’s efforts to frame Malay Muslims as part of global and regional jihadi organisations, something that many local Thai Buddhists have come to believe.

Threats to Regional Stability

Dynamics in Myanmar, Sri Lanka, and Thailand suggest the possibility of a widening Buddhist-Muslim fault line in the region. Neighbouring Muslim-majority countries have been vocal in their criticism of Naypyidaw and Colombo for failing to protect Muslim communities from violent attacks. Buddhist migrant workers from Myanmar have been attacked in Malaysia, as have Rakhine Buddhist residents in Bangladesh. There has also been a foiled attack on Myanmar’s Jakarta embassy in May 2013; a bombing in India of the Mahabodhi Temple, the site where Gautama Buddha is believed to have attained enlightenment, in July 2013; and a bombing the following month of a Buddhist centre in Indonesia.

All these attacks have been blamed on violent Muslim groups and were apparently intended as retaliation for attacks on Muslim communities in Buddhist-majority countries. Such incidents suggest there is a risk of hardening Buddhist-Muslim fault lines domestically, of Buddhist-Muslim violence spreading across the region, and of attacks by violent foreign Islamist organisations in Myanmar, Sri Lanka, and Thailand. However, it is important not to be overly alarmist. It is worth noting, for example that Malay insurgents in southern Thailand have remained distant from international jihadi organisations.

Responding to the Tensions

Interreligious tensions in the region cannot be ignored. Strengthening the rule of law and security – a solution advocated by some domestic and international voices – will not be enough. Moreover, it has been questioned how much the view of the concerned states differs from that of politically active clerics. Responding to these realities, many local and national efforts have been launched by concerned Buddhist and Muslim religious leaders and laypeople to address the violence. These initiatives, some with the support of international peacebuilding NGOs, have included interreligious dialogues and joint activities across faith groups as well as training of religious leaders – including monks – in conflict prevention and resolution.

One limitation of this approach is that few monks are willing to become involved in politics or take part in such initiatives. Non-political monks – the vast majority of the monkhood in South/Southeast Asia – consider it inappropriate on religious grounds to participate in political affairs, especially when violence is at play. This means that a small, but vocal group of nationalist monks continue to dominate public discussions on majority-minority relations.

On the international front, the Bangkok-based International Network of Engaged Buddhists held a large interfaith conference in Kuala Lumpur in 2013 to address interreligious violence in the region. Internationally prominent Buddhist figures such as the Dalai Lama have publicly condemned attacks on Muslim communities. The OIC has also called on governments to control violence against Muslims and has offered humanitarian help to both Buddhists and Muslims in conflict-afflicted Rakhine State. International human rights groups have also voiced concerns, though they have been more pointed in their denouncements. Amnesty International, for example, has accused Naypyidaw of committing ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity against the Rohingya with the support of nationalist monks.

However, as the general indignation over Time magazine’s damning report on 969 and its spiritual leader Ashin Wirathu demonstrated, such external condemnation is only likely to reinforce the perception among many of South and Southeast Asia’s Buddhists that they are maligned and misunderstood. A potentially more fruitful approach would be to engage with Buddhist nationalism to understand its concerns and address its fears. Only then will it become possible to find sustainable solutions to interreligious violence in South and Southeast Asia.

About the Author

Sabina Stein is a Researcher in the Mediation Support Team at the Center for Security Studies (CSS) and a Program Officer in the CSS project “Culture and Religion in Mediation” (CARIM).

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.

No comments:

Post a Comment