Iran has achieved milestones of leverage and influence that rival any regional power in the past half-century. While there are limits to how far it can extend its authority, Tehran’s rapid rise poses new challenges to the US, Israel, and Saudi Arabia as it undermines their previous dominance. How far can Tehran extend its reach?

Iran has achieved milestones of leverage and influence that rival any regional power in the past half-century. While there are limits to how far it can extend its authority, Tehran’s rapid rise poses new challenges to the US, Israel, and Saudi Arabia as it undermines their previous dominance. How far can Tehran extend its reach?

DECEMBER 17, 2017 BAGHDAD; AND KABUL, AFGHANISTAN—With opulent furnishings and the finest cut-crystal water glasses in Baghdad, the new offices of the Iranian-backed Shiite militia exude money and power – exactly as they are meant to. At one end of the meeting room is a set built for TV interviews, with gilded chairs and an official-looking backdrop of Iraqi and militia flags, lit by an ornate glass chandelier.

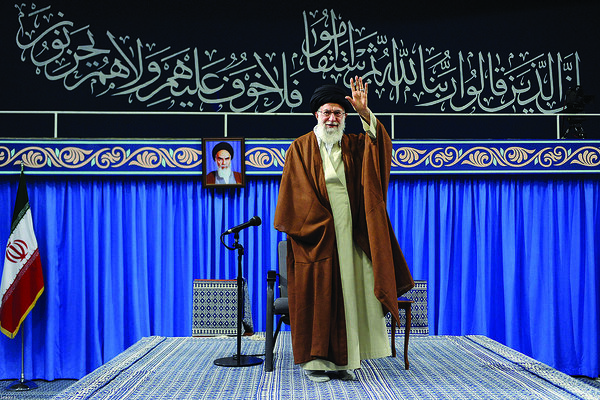

A large portrait of Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, hangs unapologetically in the next room, signaling that Harakat Hezbollah al-Nujaba is one of 44 Shiite militias – out of 66 active on Iraq’s front lines – that are loyal to Iran’s leadership.

An article of faith – universally accepted in Baghdad – is that Iran’s immediate intervention in June 2014 stopped the swift advance of Islamic State (ISIS) and “saved” the Iraqi capital, while the United States waffled and delayed responding for months, abandoning Iraq during its hour of need.

“If there were no Iranian weapons, then ISIS would be sitting on this couch,” says Hashem al-Mousawi, a spokesman for Nujaba, gesturing toward an overstuffed sofa as an aide serves chewy nougats from Iran.

Until now, Shiite Iran had met with only limited success trying to expand its influence across the mostly Sunni Islamic world, despite the call decades ago to “export the revolution” by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the leader of Iran’s 1979 Islamic Revolution.

But today – on the back of years of Iranian military intervention to fight ISIS and bolster its allies abroad, years of diminishing US leadership, and repeatedly outsmarting and outmuscling its chief regional rival, Sunni Saudi Arabia – Iran has emerged as the dominant power in the region.

One narrative of the modern Middle East is of potentates trying to stamp their imprint across these often volatile states. From Egypt’s Pan-Arabist Gamal Abdel Nasser, to Iraq’s Saddam Hussein, to the theocrats in Tehran today, the region has served as the world’s premier crucible for rulers to forge geopolitical hegemony, often with failed results. This is to say nothing of the intrusive meddling of the US, Russia, and other outside powers over the decades.

But now Iran has achieved milestones of leverage and influence that rival any regional power in the past half-century. While there are limits to how far it can extend its authority, Tehran’s rapid rise poses new challenges to the US, Israel, and Saudi Arabia as it undermines their previous dominance. In a region already reeling from multiple wars, the residue of the Arab Spring uprisings, and a deepening Sunni-Shiite divide, the fundamental question is this: How far can Tehran extend its reach?

Ironically, the first steps of Iran’s ascendancy came as a result of American actions. US forces ousted the Taliban in Afghanistan in 2001, and toppled Iraqi dictator Saddam in 2003 – both strategic enemies on Iran’s flanks. But it has been Iran’s own moves since 2011, in combination with the stepped-up dedication of its allies – especially Russia – and lack of devotion of its enemies, that have resulted in Iran’s new regional status.

Helping to defeat ISIS was a particularly exultant moment for the theocratic state. Iran has long accused the US of creating ISIS in the first place – citing Donald Trump’s frequent allegations on the campaign trail that President Barack Obama was the “founder” of the terrorist organization.

Declaring victory over ISIS in late November, Mr. Khamenei called it a “divine triumph” of the Iranian-led “axis of resistance.” Iran’s president, Hassan Rouhani, decreed Oct. 23: “Without Iran ... no fateful step can be taken in Iraq, Syria, North Africa, and the Persian Gulf.”

Declaring victory over ISIS in late November, Mr. Khamenei called it a “divine triumph” of the Iranian-led “axis of resistance.” Iran’s president, Hassan Rouhani, decreed Oct. 23: “Without Iran ... no fateful step can be taken in Iraq, Syria, North Africa, and the Persian Gulf.”

No doubt the US-led coalition and its more than 25,000 airstrikes contributed hugely to crushing ISIS and forcing it out of Iraq and Syria, as have the 3,000 American military advisers helping to rebuild Iraq’s armed forces. And no doubt Russian air power has been crucial to the survival of Iran’s beleaguered ally, Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.

But Iran has dramatically reshaped regional power structures in its favor through a pattern of pragmatic and often risky moves. Many revolve around creating and marshaling proxy, mostly Shiite, forces from as far away as Pakistan to fight on its foreign battlefields.

This gives it an edge over rivals such as Saudi Arabia, which has flailed in its attempts to push back against Tehran’s growing influence. Saudi Arabia’s young Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman has called Khamenei “the new Hitler of the Middle East,” but the kingdom has been unable to slow Iran’s rise.

In its latest counterattack, for example, Saudi Arabia orchestrated the abrupt resignation in early November of Lebanese Prime Minister Saad Hariri, its most important Sunni political bulwark against the power of Shiite Hezbollah – and its patron, Iran – in a delicate coalition government.

Mr. Hariri, in his departure speech reportedly written by Saudi hands, said, “Wherever Iran settles, it sows discord, devastation and destruction, proven by its interference in the internal affairs of Arab countries.” Iran’s hands “will be cut off.” Instead, Hariri returned to Beirut a couple of weeks later, greeted the Iranian ambassador among well-wishers, and suspended his resignation.

Another example is Yemen, where Saudi Arabia has waged a 2-1/2-year war disastrous for civilians – with critical US military support – ostensibly to “roll back” Iranian-affiliated Houthi rebels. So far the results are an estimated 10,000 dead, hospitals and historical districts turned into rubble, and a Saudi blockade that exacerbates disease and mass starvation in one of the poorest nations on earth.

Israel also sees the threat from pro-Iranian forces gaining strength along its borders. Lebanese Hezbollah, created by Iran during Israel’s 1982 invasion of Lebanon, has served as a model for Iran’s newer proxy forces and has grown battle-hardened in the Syrian civil war.

“In historical terms, Iran has never had such a powerful position,” says Fawaz Gerges, a Mideast scholar at the London School of Economics and Political Science.

“In historical terms, Iran has never had such a powerful position,” says Fawaz Gerges, a Mideast scholar at the London School of Economics and Political Science.

“Iran made a conscious decision to invest both blood and treasure, particularly in Syria, and the odds were against Iranian influence,” adds Mr. Gerges, author of “ISIS: A History.” “Everyone, including myself, thought that Iran had made the wrong choices, that Iran would lose and ... was trying to shore up a dying regime. In fact, in terms of geostrategic influence, Iranian investment in Syria – billions of dollars and hundreds killed – is the spearhead that has allowed Iranian influence to spread.”

Iran hasn’t been immune from the violence engulfing much of the region. A double ISIS attack last June on Iran’s parliament and the Khomeini mausoleum in Tehran killed at least 17. It shocked the country and reinforced the official “fight them abroad, not at home” justification for Iran’s foreign adventures.

The country faces formidable risks in its outside military ventures, too: Every theater of war where Iran has been active has seen an uptick of Shiite versus Sunni sectarianism, which complicates Tehran’s ability to establish control. And there are risks of blowback against Arab Shiites, who may be seen by Sunnis and others as doing Iran’s bidding, further undermining Tehran’s influence.

Nevertheless, across the region Iran has improved its leverage using astute, asymmetrical means despite limited military resources. Three countries in particular – Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan – illustrate how Iran has expanded its power and highlight some of the risks it faces with its newfound clout.

In Syria, Iran has been key to achieving what Mr. Obama said years ago was not possible: the survival of the Assad regime, and a military “victory” over both ISIS and anti-Assad rebel forces once backed by the US, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and Jordan.

Aside from sending hundreds of its own advisers to Syria, Iran helped persuade Hezbollah to fight in the country soon after an Arab Spring uprising began in 2011. Tehran deployed Shiite units from Iraq, raised a pro-Assad militia, and later recruited Afghans and Pakistanis to fight in Syria as mercenaries. Maj. Gen. Qasim Soleimani, the vaunted commander of Iran’s Revolutionary Guards’ Qods Force, reportedly flew to Moscow in mid-2015 and persuaded the Kremlin to weigh in with air power, a crucial factor in helping tilt the balance of the war.

On the ground, the systematic deployment of mostly Shiite Afghans is emblematic of Iran’s tactics. The recruits often agree to fight out of a desire to work and shared religious values. A Monitor investigation found that Iran offered members of the Fatemioun Brigade, a unit made up of several thousand Afghan migrants, as much as $700 a month, plus Iranian citizenship, houses, and long-term family support and education, if they took up arms.

Other migrants are intimidated or coerced into joining. Videos of captured Afghan fighters show many living in rudimentary conditions, exhibiting limited military training, and unable to speak Arabic.

“Iran has become an unrivaled regional superpower using proxy communities and proxy fighters ... as effective tools to spread [its] influence far and wide,” says Gerges.

“Iran has become an unrivaled regional superpower using proxy communities and proxy fighters ... as effective tools to spread [its] influence far and wide,” says Gerges.

The price has been high, both for Iran and its mercenaries. More than 500 Revolutionary Guards have died fighting in Syria since 2012, including a number of generals, according to tabulations by Washington-based analyst Ali Alfoneh. Hezbollah has lost 1,200 fighters, and more than 800 Afghans have perished.

Iran’s image has taken a hit, too. It has been backing a Syrian regime accused of multiple war crimes, from the use of chemical weapons to indiscriminate dropping of barrel bombs on civilian targets. Overall, the conflict has left as many as 470,000 dead and displaced more than half of Syria’s prewar population of 22 million.

Iran’s use of proxy forces in Iraq stretches back to 1982. That was the year Tehran formed the Supreme Council of the Islamic Revolution in Iraq and its 10,000-strong Badr Brigade militia. These forces fought against Saddam during the Iran-Iraq War in the 1980s, and took part in a failed Shiite uprising in Iraq in 1991. Today some of the most pro-Iran militias in Iraq trace their lineage to Tehran’s support for anti-Saddam groups.

As regimes changed, so did targets. Starting as early as 2004, Iran-backed Shiite militias battled US troops in Iraq. They inflicted heavy American casualties and introduced noxious weapons such as the “explosively formed penetrator” – a device that could blast a lethal slug of molten copper through a vehicle. But these forces faded after the US withdrawal in 2011.

Iraq’s Shiite militias were reinvigorated in mid-2014 with the advance of ISIS. Iraq’s top religious authority, Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, issued a fatwa calling on all able-bodied men to take up arms as ISIS forces pushed perilously close to Baghdad.

Iran moved quickly to shore up Iraq’s crumbling forces and took advantage of the fatwa, analysts say, to expand a network of well-financed Shiite militias that now number an estimated 150,000 fighters. Iran also poured arms and hardware into Iraq – $10 billion worth in 2014 alone.

The controversial militias are widely seen as tools of influence by Iran, though they operate under the umbrella of the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF, or hashd al-sha’abi), which Iraqi lawmakers last December voted to officially incorporate into Iraq’s security forces. Harboring similar religious motivations with Iran, the militias sometimes enter battle wearing pins and waving banners with images of Iranian ayatollahs and generals.

US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson said in October that, with the anti-ISIS fight coming to a close, “Iranian militias that are in Iraq ... need to go home.” Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif responded with a tweet: “Exactly what country is it that Iraqis who rose up to defend their homes against ISIS return to?”

“There is not a single part of Iraq without Iran,” says Hisham al-Hashemi, a defense analyst in Baghdad. “You find Iran in every detail.”

Indeed, shops are stocked with Iranian goods, and several million Iranians partake in an annual pilgrimage to Shiite shrines. Though Iraqi lawmakers have banned the militias from playing an overt role in politics, 28 political parties affiliated with the militias are already registered for 2018 elections.

Iran reportedly helped orchestrate the removal of Finance Minister Hoshyar Zebari last fall because he was considered too close to the US. Mr. Hashemi notes that the Iranians are intimately involved in Iraq’s security, politics, and economy, not to mention exert indirect influence over more than 58 TV and radio outlets and newspapers.

“Iran wanted to make Iraq only one entity, only Shiites,” he says. “Who is controlling Iraq now? Only Shiites. It is a big victory.”

Nowhere is Iran’s influence more obvious than in the headquarters of Iraq’s most pro-Iran militias, such as the Nujaba. It is here, sipping water from crystalline glasses, that pains are taken to explain how the loyalty of Nujaba’s 10,000 fighters to Khamenei – as the embodiment of Iran’s system of velayat-e faqih, supreme religious rule – is not the same as loyalty to Iran.

Nujaba has its own satellite TV station, and its propaganda videos highlight its fight in Syria around Aleppo. Nujaba’s leader, cleric Akram Kaabi, has been feted in Tehran and – echoing Iran – vows to carry on the fight, post-ISIS, against Israel.

“We don’t belong to Iran,” says Mousawi, the Nujaba spokesman. “If you follow velayat-e faqih, it is not an illegal crime.”

He draws a comparison with Roman Catholics and Pope Francis, who is Argentine. “So are the people who follow the pope agents for Argentina?” asks Mousawi. “If you follow the pope and the Vatican, do the people of your country say you are a traitor, and follow the Vatican?”

Similar views are heard in the offices of the Iranian-backed Khorasani Brigade militia. This unit also fought against ISIS and in Syria, at Iran’s request. But its members consider themselves Iraqi nationalists, says Khudayer al-Amara, a ranking member of the brigade’s Islamic al-Taleea Party. “It’s not necessary for all members to follow velayat,” says Mr. Amara. “They are unified to defend Iraq [and] defend victims of injustice. They think, when they fight in Syria, it’s the same battle as in Iraq.”

“If you ask me, the revolution of Khomeini and Iran has succeeded by exporting its revolution,” adds Amara. “Hezbollah and its followers believe in that revolution.... You can say that we [Iraqi militias] look like Hezbollah now – but we are Iraqi.”

Still, there are limits to Iran’s influence in Iraq. Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi has welcomed Iranian support but chosen a firmly nationalist path that also embraces the US-led coalition. In mid-2015, Mr. Abadi rejected an offer for Iraq to join an Iran- and Russia-led “Coalition 2.0.”

“Iran saved us. They later sent us the invoice, but they saved us,” says an Iraqi analyst who has worked for the Defense Ministry in Baghdad. “They literally sent us an invoice for the weaponry, the bullets, and the ammo that they gave us to fight ISIS, [which] proved to people that Iran does not look out for Shiite interests. Iran looks out for Iranian interests, period.”

The Shiite militias also may get more credit for military triumphs than they deserve. When he visited Fallujah during the mid-2016 fight, for example, the defense analyst says he saw no sign of the militias. But afterward, “I saw nothing but hashd, and their posters, and their flags,” he says. “They’re good at PR. You’d think they liberated the place.”

Nor are the flags always welcome. “We need to keep in mind that there was an awful eight-year war fought with Iran,” says the defense analyst, and Iraqis “don’t forget.”

The US still plays a significant role in Iraq, too. It gave Baghdad $5.3 billion in foreign aid in 2016 alone and lost 4,500 US soldiers. The US ambassador meets with the Iraqi defense minister every week. Abadi’s official website is full of pictures of the Iraqi premier meeting senior Americans officials. Iranians are absent. Such high-level contact has some Iraqis asking if the Americans, not the Iranians, should back off.

“You cannot discount Iraqi nationalism, especially after literally thousands of people – militias, Iraqi Army, Interior Ministry – have laid their lives on the line for the country,” says the defense analyst. “People say, ‘You’ve got to look at what Iran is doing with Hezbollah, in Syria.’ No, Iran looks after No. 1. As America does. And we [Iraqis] do as well.”

“You cannot discount Iraqi nationalism, especially after literally thousands of people – militias, Iraqi Army, Interior Ministry – have laid their lives on the line for the country,” says the defense analyst. “People say, ‘You’ve got to look at what Iran is doing with Hezbollah, in Syria.’ No, Iran looks after No. 1. As America does. And we [Iraqis] do as well.”

Iran must tread carefully in Afghanistan, too. It supports the government of President Ashraf Ghani – but also has given calibrated support to the Taliban for at least a decade to help it attack US forces, and more recently to crush ISIS.

Afghan government forces hold little sway over their Wild West border with Iran, where ISIS first popped up in 2014. But the Taliban does – and has proved to be an ideal tool for Iran’s buffer policy.

“For stopping ISIS, the best alternative is the Taliban, so it is easy for Iran to support the Taliban,” says Daoud Naji, a leader of Afghanistan’s Shiite Hazara community in Kabul. Proof of the brutal result came to him with pictures of dead ISIS fighters from an eyewitness. “The Taliban hung them, ISIS people, out on trees for weeks, and no one was allowed to take them down,” says Mr. Naji. “When Iran hit them strongly, [the ISIS fighters] moved to the east.”

That narrative is borne out by a map used by Afghanistan’s intelligence service, the National Directorate of Security. It shows ISIS emerging at points along Iran’s border in 2014-15, and then shifting east toward Pakistan’s border. “It’s a smart policy, to be honest,” says a Western official in Kabul.

It also benefits the US, he says. In 2014, Taliban defectors started aligning themselves with ISIS. “Was it US Special Forces that nipped that in the bud? No, it was probably Iranian-backed Taliban.... They have succeeded in stamping out the presence of self-declared ISIS groups in any province that borders Iran,” says the Western official.

Tehran’s main interest is preventing ISIS from crossing into Iran. Last year, Iran’s hard-line Kayhan newspaper described how Afghan recruits were taken for 25 to 35 days to a “special training base.” An Afghan intelligence operator confirms the base is in Birjand, an Iranian city 75 miles from the Afghan border. Of those sent there, 75 percent would go on to fight in Syria, while the remainder were shipped back to Afghanistan to work with the Taliban or attempt to infiltrate ISIS.

“Their job is to stop ISIS at the border,” he says. “They infiltrate ISIS ... but work for Iran. This is a new strategy for them.”

Still, Iran’s presence in Afghanistan continues to anger Kabul. Afghan security forces have arrested 50 or 60 people working for Iran in the past year, and “we have a plan to arrest more and more,” says the source. “They are ... using Afghan people like weapons against ISIS.” Some of those arrested are Afghans with Iranian identity cards; others are Iranian intelligence agents, he claims.

For now, Iran’s proxy strategy, in Afghanistan and across the Middle East, is giving Tehran unprecedented influence. The question: Will that bring more power or only more problems?

No comments:

Post a Comment