BY Michael J. Coren

The Federal Communications Commission has announced a total repeal of Obama-era net neutrality rules, a sweeping rejection of Obama-era rules meant to keep the internet a level playing field and prevent companies from charging additional fees for faster internet access. US telecoms have pledged to broadly respect net neutrality principles, however, and this ruling will give internet service providers the freedom to experiment with new pricing models and prioritization of content.

The Federal Communications Commission has announced a total repeal of Obama-era net neutrality rules, a sweeping rejection of Obama-era rules meant to keep the internet a level playing field and prevent companies from charging additional fees for faster internet access. US telecoms have pledged to broadly respect net neutrality principles, however, and this ruling will give internet service providers the freedom to experiment with new pricing models and prioritization of content.

The principle of net neutrality is simple: companies that connect you to the internet must treat all content equally. In policy terms, that means the government ensures internet service providers do not block, slow, or otherwise discriminate against certain content or applications.

In the US, this policy was enshrined in the Open Internet Order in 2015, when the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) passed its strongest net neutrality policies to date. The current FCC chairman, Ajit Pai, is now preparing to roll those back. His main objection, Pai told PBS, is that the rules hinder investment in expanding broadband. “My concern is that, by imposing those heavy-handed economic regulations on internet service providers big and small, we could end up disincentivizing companies from wanting to build out internet access to a lot of parts of the country, in low-income, urban and rural areas,” he said.

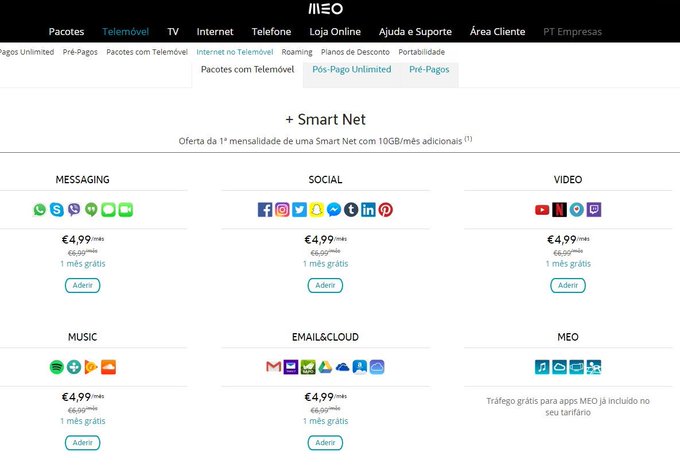

The proposal has sparked a backlash by critics who say it will result in a rich and poor internet. Companies willing to pay ISPs such as Verizon and Comcast will get faster, favored service. Companies unable or unwilling to fork out the cash will find it hard to compete, while customers may see their internet service offered in tiered “bundles,” similar to the way television channels are grouped by cable providers.

Consider Spain and Portugal. Lisbon-based telecommunications firm MEO has been rolling out mobile packages (link in Portuguese) that provide users with add-on data plans limited to specific apps. This does not block content, but using data for apps outside the package would ultimately cost more relative to those in the preferred packages. It was not clear if companies paid to be included in the packages.

“[That’s] a huge advantage for entrenched companies, but it totally ices out startups trying to get in front of people which stifles innovation,” wrote Silicon Valley congressional representative Ro Khanna on Twitter. “This is what’s at stake and that’s why we have to save net neutrality.”

In Portugal, with no net neutrality, internet providers are starting to split the net into packages.

In the US, opponents of the FCC’s net neutrality authority have argued telecoms have already agreed to its basic principles, so statutory limitations are overkill. Yet the idea that the public should trust telecoms to abide by voluntary principles, or expect the FCC to closely police corporations violating them, may not hold water with the public. Customers consistently rank telcos among their least favorite companies, reports IBM, and the FCC’s prominent actions under Donald Trump have been about rolling back rules, not citing major corporations.

Most contentious is the claim by critics of “government-run internet” that internet service providers (ISPs) have not been caught publicly discriminating against content. That will be news to Netflix. Back in 2014, the communications firm Level 3 accused six ISPs of degrading internet services for companies like Netflix, a process known as paid peering, to secure payments. “They are deliberately harming the service they deliver to their paying customers,” the firm reported. “They are not allowing us to fulfill the requests their customers make for content.”

Netflix has been particularly outspoken about these practices in the past. Not today. Netflix’s streaming traffic has grown so large that it now has far more leverage over ISPs. Netflix CEO Reed Hastings said in May that “we’re big enough to get the deals we want.”

“It’s not our primary battle at this point,” he added. “We had to carry the water when we were growing up and we were small, and now other companies need to be on that leading edge.”

No comments:

Post a Comment