By Martin Zapfe

NATO faces an existential challenge by a revanchist Russia. Despite impressive assurance and adaptation measures, its overall defense position remains weak. It will face serious challenges in balancing strategic divergence, both within Europe and in its transatlantic relations. While regionalization and increased European efforts might offer some respite, the stage is set for potentially serious rifts at a critical point in time.

NATO faces an existential challenge by a revanchist Russia. Despite impressive assurance and adaptation measures, its overall defense position remains weak. It will face serious challenges in balancing strategic divergence, both within Europe and in its transatlantic relations. While regionalization and increased European efforts might offer some respite, the stage is set for potentially serious rifts at a critical point in time.

US Defense Secretary Jim Mattis and NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg during a NATO defense ministers meeting at NATO headquarters in Brussels, Belgium, 15 February 2017.

The Atlantic alliance is both more relevant, and more threatened by internal disturbances, than ever before since the end of the Cold War. At least since Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea and subsequent invasion of eastern Ukraine, European states and their militaries have had to accept that they have to use the current time of peace to think potential war. At the same time, the Russian challenge goes far beyond conventional military threats, opting instead for “cross-domain coercion”1 from sub-conventional to nuclear means and methods. The target is cohesion within NATO – weakening the transatlantic link and supranational European institutions – a policy of constant divide and rule. It is at this critical point that the presidency of Donald Trump appears to threaten NATO from within.

This chapter argues that NATO’s adaptation towards countering the Russian challenge since 2014 is impressive. Nevertheless, although achieved at high political cost, it still risks falling short. Further tangible steps are necessary to deter Moscow, and yet internal strategic divergences within NATO threaten to hamper or block such measures. It is here that the external and internal threats to NATO converge.

The US is NATO’s indispensable ally, the political and military core of the alliance. However, it is unlikely that NATO can insulate itself from global US conflicts under a President Donald Trump who appears to follow a strictly transactionist understanding of foreign policy. The US could very well impose conditions on its security guarantees, and other alliance members may find that increasing their defense budgets, while necessary and imminent, might not be enough. Although there are ways for “institutional NATO” to mitigate the strategic divergences within the alliance, they each come with distinct risks attached and will not be a substitute for US leadership and capabilities.

The Russian Threat and NATO’s Response

A Threat to Cohesion

European states are facing many and complex security challenges. Migration pressures, terrorism, and fragile states at their periphery demand attention. However, the challenge posed by Russia under President Vladimir Putin is of a different quality, as it targets the very basis of the order that, after the end of the Second World War, enabled the longest period of peace in written European history – and a democratic, prosperous peace as well. Both with its aggression against Ukraine and with the largely sub-conventional, “hybrid” nature of this aggression, Russia has crossed lines that only a few years ago were considered inviolable. The Russian challenge is existential in that it combines external and internal threats: Russia poses the only credible territorial threat to a NATO member while actively aiming to subverting not only the inter- and supranational European alliances, but the democratic order of European states per se.

First, the annexation of Crimea marked the first armed land grab in Europe since the end of the Second World War. Six decades of general peace were partly made possible through the official renunciation of territorial ambitions and irredentism. Borders, while changeable in principle, were to be inviolable, as laid down in the Helsinki Final Act of 1975 and confirmed in the Paris Charter of 1990. Even through the bloody wars of Yugoslav succession, this principle was generally upheld. Kosovo, for all the debate about it constituting a precedent for Crimea, was not invaded by any Western state for the sake of territorial gains. The Russian attack against Ukraine to prevent the nation’s movement towards Europe was and remains a watershed predicted by very few within and outside of NATO.

Second, the “hybrid”, ostensibly covert nature of the invasion, which was long denied by Russian authorities, appears to augur the “new normal” in Russian-European relations. Russia’s understanding of interstate relations as a continuum of conflict, where the choice of means is not dictated by questions of legality, but of practicability, is diametrically opposed to the conduct of diplomacy and the understanding of interstate relations from the European point of view. Russia’s concept of “new-generation warfare” consciously and explicitly denies the distinction between war and peace as separate spheres. This overburdens the West’s ability to formulate policy responses.2 In addition, Russia has demonstrated that its understanding of information warfare (IW) as an integral part of cyber-operations aims at a soft spot in the West’s defense – its normative and legal distinction between the military and civilian spheres, and its commitment to the principle of a free press. The influence operations conducted daily in Western societies, most prominently the hack-and-release operation to influence the outcome of the US presidential election in 2016, aim at weakening the democratic societies of the West and their trust in the democratic process of governance.3

Adaptation Falls Short

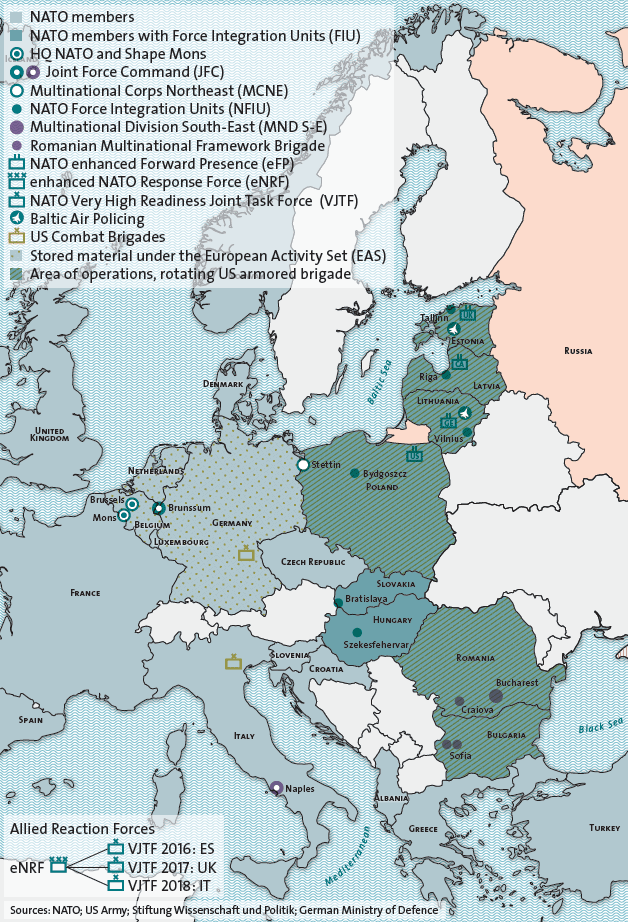

NATO stepped up to the challenge in ways that not too many observers had expected. In the mere three years since the Wales Summit of 2014, NATO has implemented the “Readiness Action Plan” and taken important and far-reaching steps to reassure allies and adapt to the new challenges for a credible defense of the exposed allies in the east – first and foremost, the Baltic states. It has established the so-called “Very High Readiness Joint Task Force” (VJTF) as its spearhead, it has enhanced the NATO Response Force (“eNRF”), it has established eight small headquarters in the eastern member states to facilitate quick deployments, and it has adapted its Force and Command Structure. The next, logical step at the alliance’s July 2016 summit in Warsaw was the decision to deploy four multinational battalion-sized battlegroups as the “Enhanced Forward Presence” (EFP).

On top of these multilateral measures, the US, under the administration of former US president Barack Obama, significantly increased its military commitment to Europe. In addition to the two combat brigades continuously stationed in Germany and Italy, armored brigades will rotate in nine-month cycles into eastern Europe to train with local forces, and equipment for another armored brigade will be stored in Belgium, the Netherlands, and Germany. Three years after the invasion of Crimea, Russia will be facing an unprecedented – if still merely symbolic – NATO presence at its borders and reinforced US troops in Europe.

Compared to where the alliance stood when Russia invaded Ukraine – with limited plans, no significant presence, and a diminished institutional memory of how actually to conduct territorial defense – the progress is impressive. Judging by whether these measures, by themselves, could credibly deter a Russian aggression in the most feared scenarios, however, the answer appears to be negative. Until it is backed up by credible capabilities, rehearsed contingency plans, and demonstrated political will, a symbolic presence in the form of a trip-wire force remains exactly that – symbolic.

For NATO, the order of the day must be twofold: politically, to preserve the cohesion of the alliance and to underline the importance of Article 5, and militarily, further to strengthen NATO’s posture in the east. This enhanced posture would allow the alliance to better resist Russian “new generation war” in peacetime and to make credible preparations for open hostilities in case of war. The agenda should be set. However, serious strategic divergences threaten to prevent this from happening.

For NATO, the order of the day must be twofold: politically, to preserve the cohesion of the alliance and to underline the importance of Article 5, and militarily, further to strengthen NATO’s posture in the east. This enhanced posture would allow the alliance to better resist Russian “new generation war” in peacetime and to make credible preparations for open hostilities in case of war. The agenda should be set. However, serious strategic divergences threaten to prevent this from happening.

NATO’s Conventional Deterrence Posture

Key multilateral and US forces, key NATO command and control structure

Threats to Cohesion

“If the alliance is to remain the foundation of Western security there must be no basic disagreement on the nature of our global objectives and on the collective responsibility of the West to protect its interests.”4

Cyrus Vance, 1983

In the face of these determined Russian efforts to undermine it, NATO faces a period of not unprecedented, yet serious strategic divergence. Of course, the Cold War did see its share of strategic divergences and momentous political upheavals seriously affecting NATO, such as the Algerian War and the Suez Crisis during the 1950s and Greece and Turkey facing off over Cyprus in the 1960s.

What is new in 2017, though, is the potentially dangerous combination of an challenge from a revanchist Russia on the one hand, and deep insecurity about internal strategic divergences within NATO on the other. A strong and essentially unified alliance would not have to fear the destabilizing acts of an overall weaker competitor with growing, but still limited military capabilities. However, an alliance that struggles with diverse, yet subtly linked challenges does have reason for concern. The alliance is facing a serious intra-European rift about defense priorities, while simultaneously experiencing hitherto unknown doubts about the US security commitment.

A Shaky Intra-European Consensus

Many allies are preoccupied with other serious security threats, and it is in addition to the existential and therefore common challenge from Russia that these other security issues are to be seen. Jihadist terrorism, carried out by commandos sent by, or perpetrators inspired by, the so-called “Islamic State” (IS) is high on the agenda, especially in France in Belgium. At the same time, Italy is struggling with a massive movement of refugees and migrants over the Mediterranean, which is largely ignored by its northern neighbors. Paris, Brussels, and Rome look southwards, not eastwards. France has refused to lead one of the EFP’s battalions, citing strained resources, which proves that this strategic divergence has already had immediate implications for operational and politico-military matters.

The “conventional turn” of 2014 has not sufficiently strengthened NATO’s cohesion. Understood as the general tendency within the alliance to move away from troop-intensive stabilization operations and back to a general notion of collective defense, this turn had already begun with the drawdown of ISAF and was significantly reinforced by the Russian aggression against Ukraine. Contrary to the expectations of many, including this author, this did not sufficiently enhance allied solidarity, nor did it form a solid basis for the years ahead. The unprecedented and unexpected migration crisis of 2015 – 6 strained intra-European relations to the breaking point, and the challenge to the south became more prominent as the Syrian war escalated further, now with Russian troops actively supporting Bashir al- Assad. On top of that, bloody terrorist attacks in France and Belgium set the agenda and demanded political attention and bureaucratic resources.

On top of that, hugely complex and potentially bitter negotiations over the terms of the UK’s departure from the EU (“Brexit”) are to be expected. With the UK being Europe’s most important and resolute military power, it appears increasingly unlikely that the critical security relationships between London and its European partners will remain unaffected by the Brexit talks. NATO will have to struggle with increased uncertainty and acrimonious relations between the UK and its partners at the time when it can least afford them.

Finally, relations between most NATO members and Turkey are on a dangerous course. While the heavy-handed and indiscriminate crackdown against real and imagined participants of the failed coup attempt of July 2016 is observed with muted suspicion and worry, Turkey’s aims and priorities in the Syrian carnage and in the broader Middle East are also partly at odds with those of its allies. On the upside, the prospect of direct Turkish-Russian clashes, which had flared up after Turkish jets downed a Russian aircraft in northern Syria in November 2015, has faded. That fear has now been replaced by a certain weariness regarding Turkey’s internal developments and a rather spectacular rapprochement with Russia, resulting in a de-facto alliance, at least in the short term, in parts of Syria. For decades, NATO has included non-democratic states among its members, yet today, it will have to ask itself whether it can permanently endure the tensions arising from an increasingly authoritarian, undemocratic, and Islamist state in its ranks. For now, the only thing that prevents serious discussions of a “Turxit” from NATO may be the fear of what might happen if Turkey were not to be an ally, but an antagonist.

NATO and the US

During the Congo Crisis of 1960, NATO’s secretary general, the Belgian Paul-Henri Spaak, mused: “Can we, thanks to NATO, maintain a common policy on European questions and […] oppose each other on all others?” That question appears to be more relevant than ever, with the US under President Trump appearing liable to entangle the alliance in global conflicts not of its choosing.

During the Balkan wars of the 1990s, US reluctance to intervene stemmed not from an urge to abandon Europe, but from the conviction that, with the Soviet threat gone, Europe should be able to manage its strategic glacis by itself. When the US under President George W. Bush, in his neo-conservative first term, split the alliance by invading Iraq, the basic commitment to European security was never seriously questioned. “Old Europe”, and even more “New Europe”, counted on the US in the event of a still-unlikely Russian resurgence. That has already changed.

With or Against Russia?

At the beginning of 2017, the insecurity within NATO capitals over the future relationship between Moscow and Washington is perplexing. During the US presidential election campaign of 2016, incredulity over the Republican candidate’s nearly ritualistic admiration of Russia, and especially of its authoritarian president, mounted by the week; and it has not faded since the inauguration. Far more than Trump’s threats and demands regarding a fairer burden-sharing, this has fed suspicion and undermined the alliance. After all, Trump’s pressure on allies to increase their defense spending is part of a decades-old tradition, and comes only six years after the landmark 2011 speech by then-secretary of defense Robert Gates, who issued an identical threat, raising the specter of a strategic reassessment by Washington.5 Moreover, President Trump can legitimately point to the commonly agreed 2-per cent target for defense spending. Thus, his pressure on allies to increase defense budgets follows the normal playbook and would, in different times, not constitute a threat to NATO.

However, the extent to which Trump has already undermined the US security guarantees, and his surreal and positively grotesque efforts to cast Putin in a positive light, are fueling the most basic European fears of a “Yalta II”, a grand bargain between Moscow and Washington over the heads of the Europeans. Essentially, Europe fears that the US will abandon its long-term allies. Senior administration officials have so far failed to reassure the allies that their president is not serious about what he says. Thus, by increasing their defense spending – in case of Germany, quite dramatically – the Europeans are not only alleviating pressure, but also hedging their bets against the time when the US is no longer the continent’s security guarantor.

Global Allies, Always?

In addition to this intra-European dissent, the alliance faces unprecedented doubts about Washington’s essential security guarantees as a NATO member. These are compounded by the prospect of potential global turmoil, with the US under Trump refusing to allow its allies to stand by and decline involvement. In a time of growing doubts about NATO’s security, global conflicts far beyond Europe could well contribute to a transatlantic divide.

The two global theaters most likely to be at the center of forceful US foreign policy efforts – the Middle East and Asia – are liable to see severe disagreements between the US on the one hand, and most of its NATO allies on the other. While President Trump’s senior officials, namely Secretary of State Rex Tillerson and Secretary of Defense James Mattis, have tried to reassure European allies, Donald Trump made the headlines. During the campaign, he seemed to qualify US solidarity by tying it to the European states’ defense spending. Furthermore, after his inauguration, he added to that by famously calling NATO “obsolete”. Without clarifying what, precisely, he meant by this, it is clear that the US will not easily accept NATO members standing aside in US conflicts beyond the campaign against terrorism – when confronting IS, Iran, or China.

At the very least, the alliance faces intense discussions about its role in the fight against IS, and the broader Middle East as a whole. President Trump has made clear that IS constitutes his key foreign policy priority. Former and current advisors, like former national security advisor Lieutenant General Michael Flynn and White House chief strategist Stephen Bannon, viewed “radical Islamic terrorism”, if left unchecked, as a potentially existential threat to the US; they apparently wield strong influence over the president. While Trump has been famously silent on the specifics of his plans, he has hinted that he wants his NATO allies to take on a stronger role in the “fight against terror”. Since most NATO members are already engaged in the US-led coalition against IS, albeit outside of NATO, this could mean either that they would increase their engagement within this coalition, or that NATO could take over part of the campaign in what would be a largely symbolical step without too much tangible value being added to the campaign.

Such wins may not be nearly as easy to achieve when it comes to the other potential main effort of the Trump administration in the Middle East. Trump and his key advisors have been outspoken in their criticism of Iran’s role in the region and its attacks on US service members and interests. Washington’s European allies have been instrumental in negotiating the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) of 2015. They are unanimous in supporting the agreement, and have strong economic interests in expanding trade relations with Tehran. Should President Trump choose to abrogate the agreement in the absence of unambiguous Iranian violations, he could not count on European support. And should he listen to those voices around him (and in the region) who still demand US attacks on nuclear and military installations – potentially in a combined operation together with Israel – it appears highly unlikely that he could count on the active and unanimous support of NATO and its member states.

The same applies to potential conflicts in the Far East. Asian security challenges took center stage even before the inauguration after president-elect Trump upset the People’s Republic of China by accepting a phone call from Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen, who congratulated him on his victory. In the days that followed, Donald Trump made clear that this had been no mere faux-pas, but that he might assume a more confrontational policy vis-à-vis Beijing, temporarily challenging the One-China Policy and attacking the current imbalance in bilateral trade as unfair. In addition, some of his personnel picks indicate a tougher stance on Beijing.6 While one has to be careful – and President Trump has already been forced to backtrack from his challenge to the One China policy – it appears that the US under Trump will continue to confront China on many levels, notwithstanding logical inconsistencies such as the cancellation of the TPP, which decidedly disfavors Beijing.

At the same time, fears emerged concerning an early confrontation with North Korea. In the face of speculations over a test of an intercontinental missile that might be capable of reaching the US mainland, the president-elect promised via Twitter that North Korea “developing a nuclear weapon capable of reaching parts of the US [...] won’t happen”, leading to speculation over what he would do, once in office, to prevent the regime of Kim Jong-un from following through on its promises. While the response to the test of a missile with shorter range has been rather restrained, North Korea might well pose the first real test of President Trump’s foreign policy.

Few European states have a global strategic perspective. Only France and the UK, formerly the continent’s preeminent colonial powers, include global interventions in their strategic portfolio. While any of the aforementioned conflicts would immediately affect European interests, it is far from certain that the mere possibility of such outcomes could prompt European NATO members to contribute militarily to any US-Chinese or US-North Korean conflict. While the Chinese encroachment in the South China Sea, and the challenge this poses to the global rules-based order, could incite European resistance, no one should count on Berlin, Rome, or Madrid to be willing to confront China over their profound economic interests. This would be even more unlikely if, from the Europeans’ perspective, the US under Trump were to blame for any escalation.

Trump, who puts “America First” and has already stated that NATO has become obsolete by focusing on Russia as the main threat, is unlikely to accept the simple legal fact that the NATO treaty is limited to “the territory of any of the Parties in Europe or North America (and) the Islands under the jurisdiction of any of the Parties in the North Atlantic area north of the Tropic of Cancer.”7 The US president, apparently viewing international politics as purely transactional in nature, might well condition the US security guarantee for Europe on direct European assistance in the Middle East or Asia – and there is no guarantee that NATO would be willing to live up to his expectations, or indeed capable of doing so.

Mitigating Strategic Divergence

In the face of these strains on cohesion within the alliance, how can NATO leverage its institutional flexibility to mitigate the fallout? The obvious answer is increased defense spending, as the US has repeatedly demanded. This message appears to finally have been understood, and European states have pledged to increase their defense expenditures, sometimes dramatically. That alone, however, will not suffice. The institution itself must adapt, as it has always done over six decades. Three possible courses of action, which are not mutually exclusive, continue to re-appear in the debate, but none comes without costs and risks attached – and none may be easy to implement.

Regionalization as Risk and Chance

The obvious functional answer to such divergent interests, at least regarding the European allies and their respective priorities, would be a regionalization of the alliance – meaning the acceptance that certain potentially overlapping groups of allies prioritize certain regions or challenges. Such a regionalization is at odds with NATO’s historical approach and, while having undisputable benefits, would entail the risk of further diminishing unity in case of conflict.

For NATO, this means accepting strategic divergence and nascent regionalization as a given and actively moderating it to contain the risks and cultivate the chances that such a trend entails. Both the advantages and the disadvantages are potentially significant. Walking the tightrope between accepting specialization and regionalization to buffer strategic divergences, while still ensuring political and military unity and interoperability across the board, appears to be one main challenge in the years to come.

NATO has always known a certain degree of regionalization. Italian troops were focused south of the Alps, while Norway guarded the north. Greece looked towards the Mediterranean, and Turkey had an eye on the Black Sea. However, the bulk of the alliance’s forces was to be fighting at Europe’s central front between the Alps and the North Sea. Here, British, Dutch, Canadian, Belgian, Danish, US, and German (and, although of varying independence, French) forces were positioned to fight side by side. Apart from the sheer necessity of fighting together to generate the numbers, this also had a very strong symbolic aspect. Most of the main allies had ground troops on the frontline. For all practical purposes, it was near impossible to opt out of any escalation – an important reassurance for all allies in general, and for the German government in particular. Buffeting the increasingly diverse strategic foci of NATO members through increased regionalization risks weakening the very cohesive forces that hold NATO together in times of crises.

However, if NATO should manage to coordinate and steer that regionalization, there would be tangible advantages. There is a considerable potential for a distinct east-south specialization – a split that, in reality, is already relevant. On the upside, such a strategy could sharpen the operational and regional focus of the alliance, increase military efficiency and efficacy for relevant contingencies, and allow for better force planning and harmonization of capabilities.

The NATO Command Structure – still the military centerpiece and most important asset of the alliance – has experienced quasi-constant reform since the end of the Cold War. Currently, it is based on functionality, not geography, meaning that no headquarters are permanently assigned to a specific region. It would seem imperative, then, for the alliance to designate a distinct and unambiguous chain of command for one single region and to focus all its bureaucratic bandwidth on war-planning, contingencies, and preparations in the assigned area of operations. For example, while the Joint Force Command Brunssum could be designated as “JFC East”, its sister command in Naples could be modeled as a “JFC South” with permanently subordinated or assigned forces, tailored to specific missions and contingencies. Recent announcements by NATO point in that direction.8

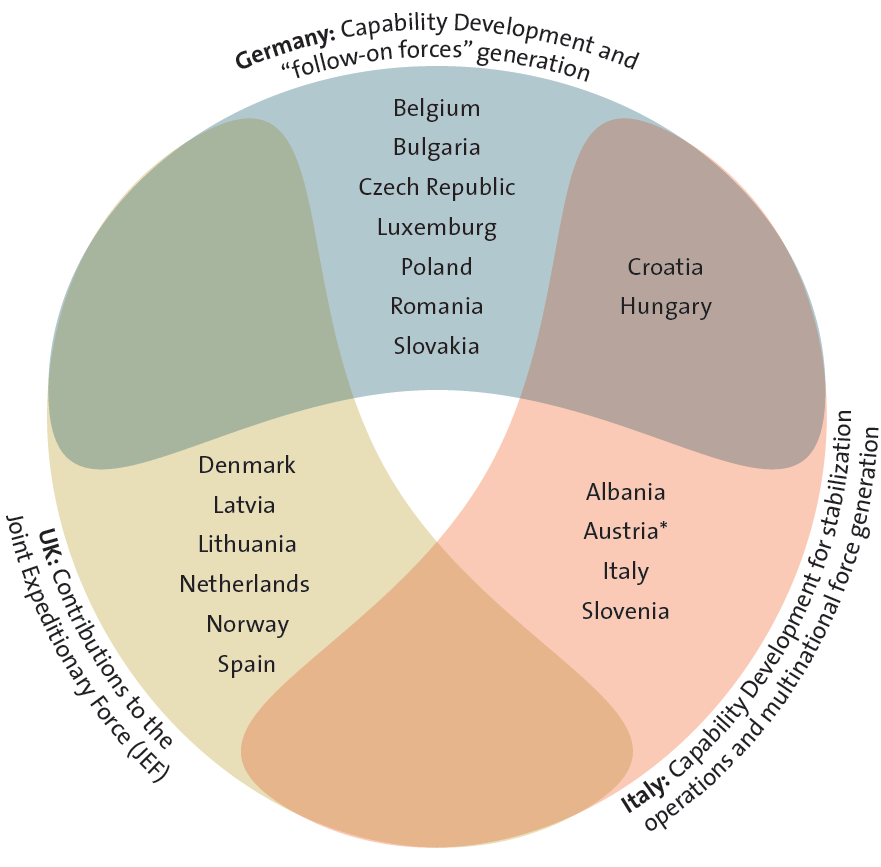

The Framework Nations’ Concept

Introduced by Germany in 2013, adopded by NATO in 2014

* Non-NATO Member. Sources: Diego A. Ruiz Palmer, “The Framework Nations’ Concept and NATO: Game-Changer for a New Strategic Era or Missed Opportunity?”, in: NATO Defense College Research Paper, no. 132 (2016); Hans Binnendijk, “NATO’s Future: A Tale of Three Summits”, Center for Transatlantic Relations (2016).

This could imply a regionalization of the alliance in terms of force generation as well. With regard to Russia, for example, such a group could form a core of nations prepared to go further in their military integration and to pledge certain capabilities with a regional focus and much deeper integration than currently achievable. Such a regionalized defense cluster would need to include the US; the “Big Three”, whose capabilities come as close to full-spectrum forces as is realistically possible, namely France, the UK, and Germany; and the eastern member states primarily affected by this threat. In addition, a certain degree of regionalization could facilitate the integration of non-members Finland and Sweden into NATO’s contingency planning, if their respective governments should choose that course.9

In the south, where various maritime and coast guard capabilities are in demand, together with stabilization capabilities, states like Italy, Spain, Portugal, and Greece would prioritize those missions.

This split is already visible in force planning: Within NATO’s “Framework Nations’ Concept” (FNC), Germany is leading efforts to generate viable so-called “follow-on forces” for the eNRF, while Italy is coordinating a group of nations focusing on stabilization operations.10

However, any regionalization would come at potentially prohibitive political and military cost. NATO has always been more than just a military organization searching for the most efficient battle plan. It is also an organization of mutual security that for 60 years has protected its member states against external enemies and promoted peaceful conflict resolution between them, as laid down in Article 1 of the North Atlantic Treaty. Thus, political unity, or the acceptance of a single basic contractual and political framework, is not just mere symbolism, but the foundation for peaceful relations between alliance members. Regionalization, if unchecked and unmoderated, could undermine this unity and degrade the North Atlantic Council (NAC) to a mere symbolic shell.

In military terms, overly specialized armed forces that are focused on a single scenario risk “preparing for the last war”, meaning that they cultivate capabilities that are relevant in the worst-case scenario, but of little use in other (and, for NATO as a whole, more relevant) scenarios. For example, should the southern states completely reorient their armed forces towards intervention and stabilization missions in the south – focusing on infantry-heavy, light and sustained low-intensity land operations to the detriment of heavy, armored, high-technology intervention forces with a priority on high-end air and naval forces – the day might come when they are not only unwilling, but also essentially unable to support the Baltic allies against a Russian incursion.

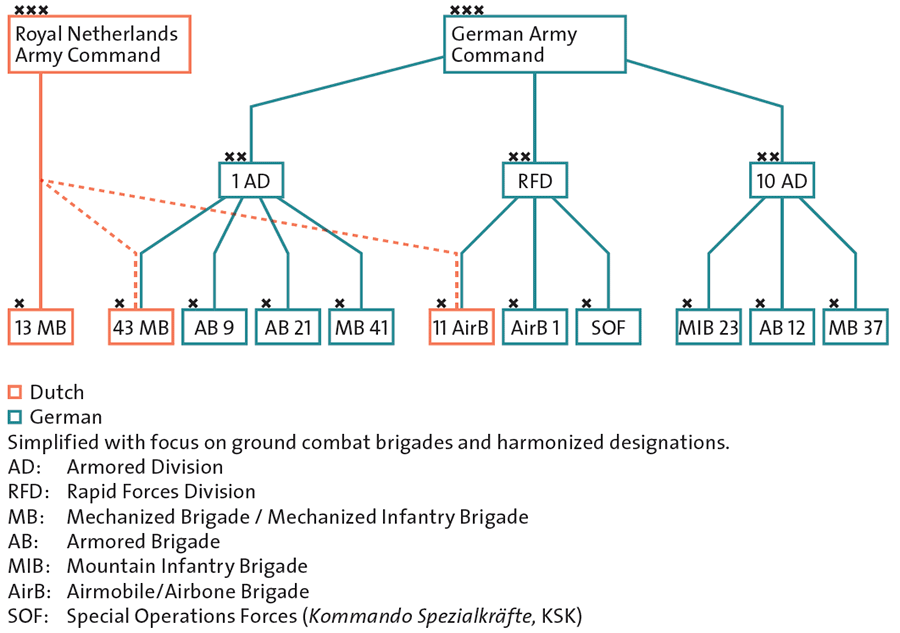

Multinational Integration in the Dutch and German Land Forces

Sources: Deutsches Heer; defensie.nl

That logic also applies conversely. As NATO might find itself fighting wars with the burden being carried by only a small number of specialized states, so increases the danger that a vanguard of willing nations could embroil NATO in a war it does not want. The organizational integration of armed forces as pursued by some allies might also reinforce this dilemma. While rightfully hailed as an important symbolic move, and with real military potential, integrating the Dutch and German land forces will only make sense if it is accompanied by a harmonization of political decisionmaking between The Hague and Berlin, which would create new power centers that could mobilize or block NATO.

The principle of collective decisionmaking thus constitutes an effective barrier against NATO being dragged into such a scenario, but a regionalized and specialized defense posture involuntarily entails informal decisionmaking groups of the most affected nations, potentially putting NATO solidarity to the test in a situation where it is far from guaranteed. Furthermore, any such development would immediately touch off the decades-old question of the alliance’s nuclear deterrence, control of relevant assets, and collective decisionmaking in nuclear scenarios. It could thus become impossible, on purely technical grounds, to uphold the hugely important principle of “all for one, one for all”.

Below and Beyond the Alliance? ‘Coalitions of the Willing’ and Unilateralism

A regionalization of NATO entails risks, and yet it would affect neither the institutions nor the logic of NATO. Every foreseeable form of regionalization would still involve the symbolic presence of at least token forces from most member states. It is precisely this logic that underwrites NATO’s EFP in the Baltics and Poland. Nevertheless, institutions can lose some of their integrative force, as illustrated by the growing trend towards what former US defense secretary Donald Rumsfeld referred to as “coalitions of the willing” within and outside of NATO. In fact, even for the most basic task of territorial defense, NATO might have to fall back on “coalitions of the willing” if it does not adequately prepare for what is still essentially its raison d’être.

Again, the concept of a group of nations resolving to act together and to move further, faster, and more efficiently than the alliance as a whole is not a totally new one. Throughout its existence, NATO’s member states have allied or cooperated for specific wars and operations, independently of their NATO commitments. Whether it was the French and British during the Suez Crisis or, naturally, the US in all its global entanglements since 1949, no article of the North Atlantic Treaty prohibits its members from going it alone. However, the current trend towards a variety of ad-hoc coalitions meets a different NATO than during the 1950s; and ad-hoc coalitions under US leadership risk relegating NATO to a backseat at a time when it needs to be front and center.

Current relevant ad-hoc coalitions can be categorized in three groups. First, allies can form ad-hoc coalitions and cooperate flexibly as well as in varying coalitions, outside of NATO, and for any conceivable scenario. Most prominently, the “Counter-Daesh” coalition fighting the so-called “Islamic State” is coordinated by US command institutions and brings together a very heterogeneous coalition of NATO and non-NATO states. While there are good reasons to circumvent the alliance in this fight, this form of ad-hoc coalition poses the least threat to NATO cohesion.

Second, NATO members can act (primarily) within the framework of the alliance, using its institutions and command structure, while others not only abstain, but oppose the operation. The 2011 Libya Campaign is an obvious case in point. During “Unified Protector”, NATO was far from unified. In the United Nations Security Council, Germany abstained from UNSC Resolution 1973 authorizing the operation, yet did not block agreement in the NAC, allowing NATO to command parts of the operation through its command structure. However, the German abstention caused not only political, but also tangible military problems. While the federal government distanced itself from the operation, more than 100 German officers supported it through their work within NATO’s Command Structure. At the same time, Germany prohibited the use of German airmen assigned to NATO’s integrated Airborne Early Warning and Control (AWACS) wing at Geilenkirchen, Germany, significantly straining allied resources in a coordination-intensive air campaign against Libyan forces.

For all its short-term successes, “Unified Protector” was an interventionist operation in NATO’s periphery without a clear and present danger to alliance – and nevertheless, it may be far-fetched to imagine a coalition of the willing within NATO operating the machinery of NATO against Russian forces without the unanimous support of the NAC. However, if regionalization is thought through to the extreme, it is not unimaginable that a high-pressure situation could lead to a wrangling NAC tacitly agreeing that selected members move the NATO machinery to action while others abstain from the vote without blocking mobilization. The dangers for allied cohesion that such a scenario would entail needs no further elaboration.

Third, NATO members could act outside of NATO’s institutions, yet within its basic politico-military logic and relevant scenarios. One potential scenario that is seldom discussed, but is highly relevant, envisages allies such as the UK and the US intervening in a Baltic invasion scenario in the face of a divided NAC blocked by hesitant allies. In that case, the nations could not use NATO’s Command Structure, but would likely use some of the same forces, and only slightly adapted operational plans, to act as NATO’s “unsanctioned vanguard”.

A theme frequently discussed among central and eastern European NATO members is that NATO’s primary designated instruments for deterring Russia – the VJTF and the eNRF being the most prominent among them – are liable to fall short due to political and military reasons. Exposed allies then point towards nations with strong military capabilities that might be willing to go above and beyond what has been authorized by a reluctant NAC and intervene on their own. This envisions US, British, or Danish troops coming to the assistance of the Baltic and Polish states far quicker and more decisively than the designated NATO units.

Setting aside the implications for NATO’s credibility of such a non-NATO vanguard countering Russia in a region that dramatically favors the Russian side, this hope for an anti-Russian coalition of the willing stands and falls with US resolve. While the UK is Europe’s prime military power, and even some smaller allies have respectable military capabilities, the US is, and remains, NATO’s indispensable nation.

Strengthening the European pillar?

After the election of Donald Trump gave rise to fears about Washington’s relations with Russia and its NATO allies, a growing number of voices responded with the familiar call for a stronger European pillar within NATO – partly to accommodate US pressure for better “burden-sharing”, and partly to prepare better for a formal or informal US withdrawal from NATO.11 While such an approach is undoubtedly important, and never more so than today, one has to be clear-eyed as to its limitations: Even in the best-case scenario, Europe is set to lose with a US withdrawal, at least for years to come.

First, the very political and institutional logic of NATO depends on the US. It is, of course, no coincidence that Europe has been united and at peace for the first time in centuries during the same time in which the US shed its tradition of shunning permanent alliances and engaged with Europe.

The political bedrock of NATO is the US determination to stay engaged, and to help defend its European allies. The US is the indispensable balancer that brings together the still-heterogeneous countries of Europe under one roof – especially the “new” member states of Central Europe, all of whom look to Washington, not Berlin, London, or Paris for political leadership and protection (not only against Moscow).

Second, NATO’s prime military asset, its integrated and tested command structure, has always been built around US capabilities and forces. Just as NATO’s supreme commander in Europe (SACEUR) is simultaneously the commander of all US forces in Europe (COM EUCOM) within the US unified command plan, US general officers form the backbone of NATO’s Command Structure. The US cannot simply withdraw from NATO’s military integration, as France did in 1966, without doing the utmost damage to the alliance’s capability for military operations.

Third, in addition to the command-and-control arrangements that are critical to any military operation, and even more so for multinational campaigns, the US provides the bulk of critical, mission-relevant, and mission-ready capabilities and forces. With regard to ground forces, even with generous counting, the major European allies would be hard-pressed to provide one combat-capable brigade at short notice. The US alone is set to have three combat brigades present in Europe at all times, plus materiel for a fourth, as well as the relevant ground enablers, including significant artillery capabilities and national command-and-control elements. Added to these are high-readiness forces in the US that can be deployed at relatively short notice over strategic distances. Moreover, if we look beyond these ground forces to air and naval capabilities, the gap between US forces and those of the other allies is even larger. The fact that NATO had to rely on US support, coordination, and supplies for a relatively minor air campaign over Libya in 2011 should caution against ambitious expectations in any real war scenario against Russia. While individual NATO members may add relevant capabilities in the area of special operations and cyber-capabilities, the US remains on a level of its own in these spheres as well.

Fourth – and re-entering the debate after years of neglect – NATO’s nuclear deterrence still is vitally dependent on US nuclear weapons and political will. Through its strategic and tactical nuclear weapons, and through the nuclear sharing arrangements with selected European nations, the US provides the nuclear umbrella for the continent. Should that umbrella weaken or even disappear, it is far from a given that the two remaining nuclear powers, France and the UK, could step into the void. Judging by the political climate that made Brexit possible, London is liable to value independence over anything else, its public support for NATO notwithstanding. Paris has always been consistent in its insistence on nuclear sovereignty. Nevertheless, even if one or both of these nations were to agree to extend their nuclear deterrence, this would hardly be an equivalent substitute for US forces. The UK only operates submarine-based strategic nuclear weapons and is technologically dependent on the US. In addition to submarines, France relies on tactical aircraft as delivery platforms. These forces are several “steps” below the capabilities that are traditionally – and increasingly – deemed necessary on the ladder of escalation. Without the US, there is no credible nuclear deterrence in NATO.12

The bottom line is that the US is and remains NATO’s indispensable nation. While fairer burden-sharing and increased European commitments will have some effects, there is no cheap and immediate shortcut for the Europeans to strengthen the “European pillar” to the point of “strategic autonomy” or even to substitute a retrenching US. In any scenario, especially regarding a revanchist Russia and its Eastern defense, there is no credible deterrence and no realistic defense of Europe, within or outside of NATO, without the US – for at least a decade to come.

A Thoroughly Political Challenge

NATO is in peril; not because the challenges are insurmountable, but because it is threatened from the outside and within, severely hampering the alliance. Within only a few years, the alliance has found itself facing a weak but determined strategic competitor, structural insecurity in its neighborhood, and existential doubts over the reliability of the indispensable ally, the US. Increased defense spending, while critical, will not suffice. Institutional adaptation might bring some respite and leverage NATO’s strengths, but comes with its own risks and costs attached.

Ultimately, the strength and cohesion of NATO as an alliance of sovereign nation-states depend on the political determination to overcome political challenges. Without Washington acknowledging that, through all disagreements, NATO is not just a means, but an end in itself, the prospects are bleak. However, for all of Russia’s determination and the credible threat that it poses, NATO is primarily threatened from within – and can thus be saved from within.

No comments:

Post a Comment