FIVE men who ran a bookshop in Hong Kong disappeared in mysterious circumstances in late 2015. One was apparently spirited away from the territory by agents from the mainland; another was abducted from Thailand. All later turned up in Chinese jails, accused of selling salacious works about the country’s leaders. One bookseller had a British passport and another a Swedish one but the two suffered the same disregard for legal process as Chinese citizens who anger the regime. Their embassies were denied access for weeks. The government considered both these men as intrinsically “Chinese”. This is indicative of a far broader attitude. China lays claim not just to booksellers in Hong Kong but, to a degree, an entire diaspora.

FIVE men who ran a bookshop in Hong Kong disappeared in mysterious circumstances in late 2015. One was apparently spirited away from the territory by agents from the mainland; another was abducted from Thailand. All later turned up in Chinese jails, accused of selling salacious works about the country’s leaders. One bookseller had a British passport and another a Swedish one but the two suffered the same disregard for legal process as Chinese citizens who anger the regime. Their embassies were denied access for weeks. The government considered both these men as intrinsically “Chinese”. This is indicative of a far broader attitude. China lays claim not just to booksellers in Hong Kong but, to a degree, an entire diaspora.

China’s foreign minister declared that Lee Bo, the British passport-holder, was “first and foremost a Chinese citizen”. The government may have reckoned that his “home-return permit”, issued to permanent residents of Hong Kong, trumped his foreign papers. Since the territory returned to mainland rule in 1997, China considers that Hong Kongers of Chinese descent are its nationals. Gui Minhai, the Swede taken from Thailand, said on Chinese television, in what was probably a forced confession: “I truly feel that I am Chinese.”

China felt it could act this way because it does not accept dual nationality. The law is ambiguous, however. It stipulates first that a person taking a foreign passport “automatically” loses their Chinese nationality and then, contradictorily, that an individual has to “renounce” their nationality (hand in their household-registration documents and passport) and that the renunciation must be approved. According to Mr Gui’s daughter, he went through the process of relinquishing his citizenship. Yet the Chinese authorities considered that his foreign passport was superseded by birth and ethnicity: both Mr Gui and Mr Lee are Han, the ethnic group that makes up 92% of mainland China’s population.

Ethnicity is central to China’s national identity. It is the Han, 1.2bn of them in mainland China alone, that most people refer to as “Chinese”, rather than the country’s minorities, numbering 110m people. Ethnicity and nationality have become almost interchangeable for China’s Han, says James Leibold of La Trobe University in Melbourne, Australia. That conflation is of fundamental importance. It defines the relations between the Han and other ethnic groups. By narrowing its legal labour market almost entirely to people of Han descent, ethnicity is shaping the country’s economy and development. And it strains foreign relations, too. Even ethnic Han whose families left for other countries generations ago are often regarded as part of a coherent national group, both by China’s government and people.

The Han take their label from the dynasty of that name in the third century BC. Yet the people labelled Han today are a construct of the early 20th century, says Frank Dikötter of the University of Hong Kong. For well over half of the past 650 years, the bulk of territory now called China was occupied by foreign powers (by Mongols from the north, then Manchus from the north-east). Chinese history paints the (foreign) Manchus who ran China’s last dynasty, the Qing, as “Sinicised”, yet recent research suggests that they kept their own language and culture, and that Qing China was part of a larger, multi-ethnic empire.

Great Wall

Under Western imperialism race was often used to divide people. But after the Qing fell in 1911, the new elite sought to create an overarching rationale for the Chinese nation state—its subjects spoke mutually incomprehensible languages and had diverse traditions and beliefs. Patrilineage was already strong in much of China: clans believed they could trace their line to a group of common ancestors. That helped Chinese nationalists develop the idea that all Han were descended from Huangdi, the “Yellow Emperor”, 5,000 years ago.

Race became a central organising principle in Republican China. Sun Yat-sen, who founded the Kuomintang, China’s nationalist party, and is widely seen as a “father” of the Chinese nation, promoted the idea of “common blood”. A century on President Xi Jinping continues to do so. One reason for his claim that Taiwan is part of China is that “blood is thicker than water”. In a speech in 2014 he set his sights even wider: “Generations of overseas Chinese never forget their home country, their origins or the blood of the Chinese nation flowing in their veins.”

Many Chinese today share the idea that a Chinese person is instantly recognisable—and that an ethnic Han must, in essence, be one of them. A young child in Beijing will openly point at someone with white or black skin and declare them a foreigner (or “person from outside country”, to translate literally). Foreign-born Han living in China are routinely told that their Mandarin should be better (in contrast to non-Han, who are praised even if they only mangle an occasional pleasantry).

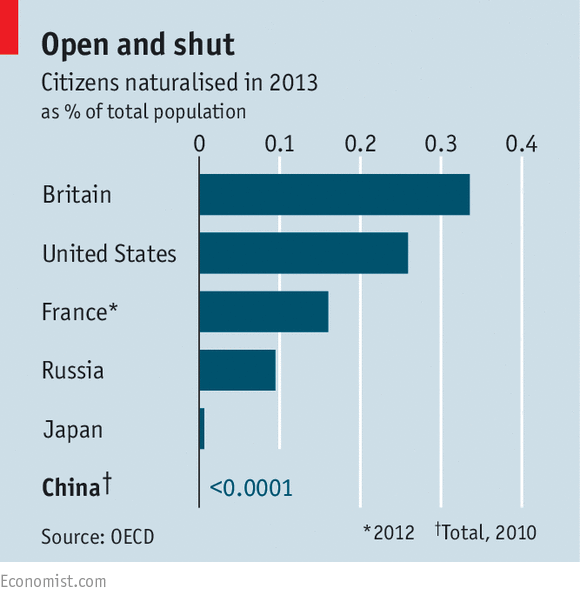

China today is extraordinarily homogenous. It sustains that by remaining almost entirely closed to new entrants except by birth. Unless someone is the child of a Chinese national, no matter how long they live there, how much money they make or tax they pay, it is virtually impossible to become a citizen. Someone who marries a Chinese person can theoretically gain citizenship; in practice few do. As a result, the most populous nation on Earth has only 1,448 naturalised Chinese in total, according to the 2010 census. Even Japan, better known for hostility to immigration, naturalises around 10,000 new citizens each year; in America the figure is some 700,000 (see chart).

China today is extraordinarily homogenous. It sustains that by remaining almost entirely closed to new entrants except by birth. Unless someone is the child of a Chinese national, no matter how long they live there, how much money they make or tax they pay, it is virtually impossible to become a citizen. Someone who marries a Chinese person can theoretically gain citizenship; in practice few do. As a result, the most populous nation on Earth has only 1,448 naturalised Chinese in total, according to the 2010 census. Even Japan, better known for hostility to immigration, naturalises around 10,000 new citizens each year; in America the figure is some 700,000 (see chart).

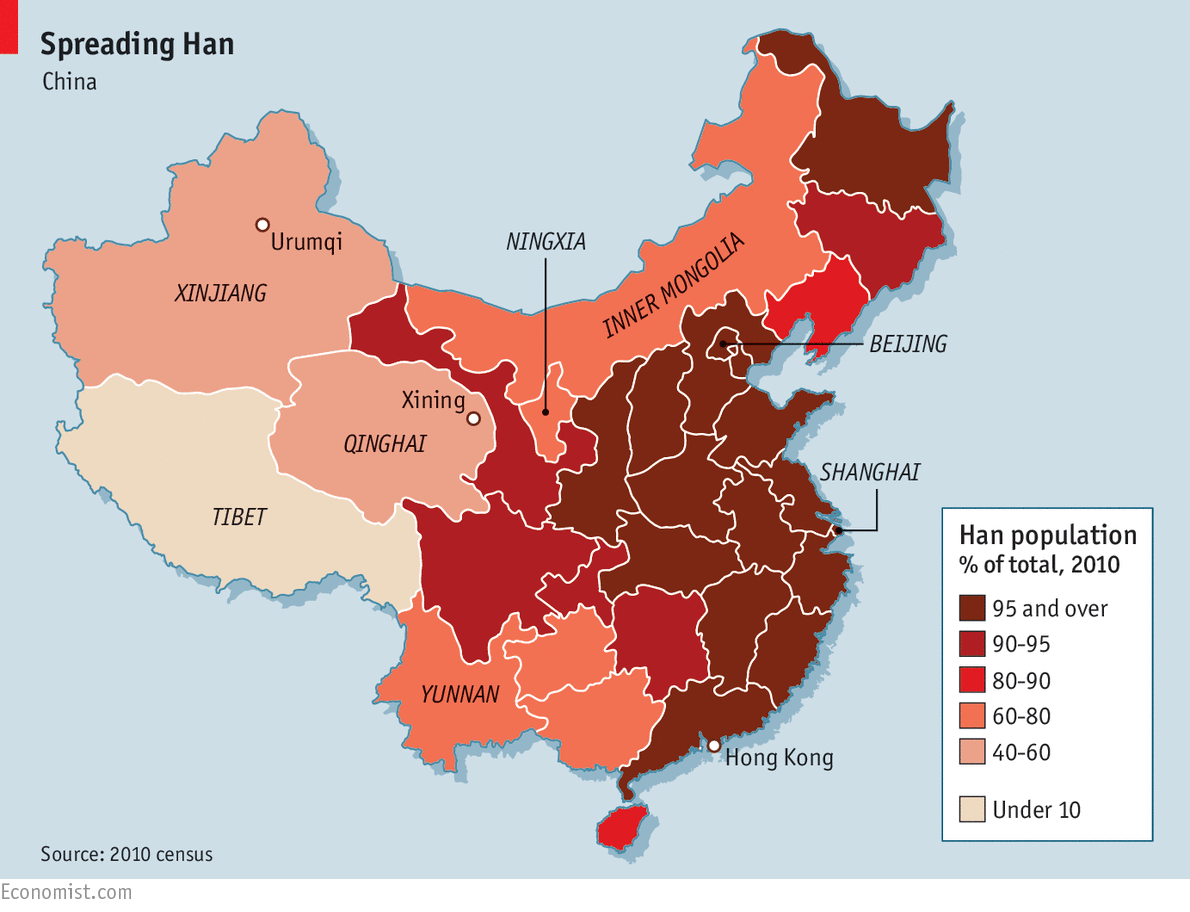

The conflation of Han and national identity underlies the uneasy relationship between that majority and China’s ethnic-minority citizens. Officialdom theoretically treats minorities as equal and even grants them certain privileges. Yet in practice ethnic groups, particularly those from China’s borderlands, who are visually distinctive, are discriminated against and increasingly marginalised as ethnic Han have moved into their home regions. Through state-sponsored resettlement the Han population of Xinjiang rose from 4% in 1949 to 42% today; Mongols now make up only 17% of Inner Mongolia (see map).

At best non-Han groups within China are patronised as “charming and colourful” curiosities. Yunnan province has built a thriving tourist industry around its minority cultures. Minorities are routinely presented as delighting in folkish customs in contrast with the technologically superior Han. In an exhibition of “Xinjiang’s nationalities” in a museum in Urumqi, the provincial capital, the only person in modern clothes is Han; signs note that Chinese Uzbeks “have a special liking for all kinds of little caps” and Chinese Kazakh life is “full of songs and rhythms”.

At best non-Han groups within China are patronised as “charming and colourful” curiosities. Yunnan province has built a thriving tourist industry around its minority cultures. Minorities are routinely presented as delighting in folkish customs in contrast with the technologically superior Han. In an exhibition of “Xinjiang’s nationalities” in a museum in Urumqi, the provincial capital, the only person in modern clothes is Han; signs note that Chinese Uzbeks “have a special liking for all kinds of little caps” and Chinese Kazakh life is “full of songs and rhythms”.

China risks turning cultural insensitivity into ethnic clashes. Ordinary manifestations of local culture in border regions have been criminalised. In Xinjiang, Uighur men may not grow long beards and Muslims are sometimes prevented from fasting during Ramadan. Inner Mongolian and Tibetan nomads have been forcibly settled. In Tibet and Xinjiang, many schools teach mostly in Mandarin, even if they lack enough Mandarin-speakers.

That legitimises prejudice in daily life. “They think of us as wild, as savage” says a Tibetan guide in Xining, the Han-dominated capital of Qinghai province on the Tibetan plateau; only one of his Han neighbours even says hello to him. Tibetans and Uighurs are routinely rejected from hotels elsewhere in China (Chinese ID cards state ethnicity). Reza Hasmath of the University of Alberta found that minority employees in Beijing were typically better educated but paid less than Han counterparts. The best jobs in minority areas go to Hans.

Chinese are now organising in small ways to fight for labour rights, gay rights and environmental concerns but there is little indication that Han are gathering to defend their ethnic peers—perhaps unsurprisingly, given that to do so could be seen as supporting separatism. If anything, the opposite is true: the government’s rhetoric, particularly on the dangers of Islam, has exacerbated existing divisions.

Hui Muslims have long been the successful face of Chinese multiculturalism: they are better integrated into Han culture and widely dispersed (importantly they speak Mandarin and often look less distinct). Yet Islamophobia is rising, particularly online; social-media posts call for Hui Muslims to “go back to the Middle East”. In July, Mr Xi used a trip to Ningxia province, the Hui heartland, to warn Chinese Muslims to resist “illegal religious infiltration activities” and “carry forward the patriotic tradition”, a sign that he views this group with suspicion, as well as those on China’s fringe with a history of separatism.

Although many of China’s citizens are not treated as equals, Han Chinese with foreign passports are welcomed and accorded a special status. Anyone with Chinese ancestry has legal advantages in getting a work visa; foreign-born children of Chinese nationals get a leg-up in applying to universities.

This attitude has helped the Chinese economy. Over the past decade much of the inward investment has come from overseas Chinese. Many second-generation Chinese-Americans have started up firms in China. Yet being a member of the “Chinese family”, as Mr Xi puts it, carries expectations too. At a reception in San Francisco last December for American families who had adopted Chinese children, China’s consul reminded them that “you are Chinese”, citing their “black eyes, black hair and dark skin”; he encouraged them to develop a “Chinese spirit”.

In the eyes of the Chinese government, these responsibilities extend beyond cultural ties to a demand for loyalty, not just to China but to the Communist Party. Many foreign Han say they are made to feel it is their duty to speak up on China’s behalf. Earlier this year Chinese immigrants to Australia were urged to take “the correct attitude” to support “the motherland” in its claims to disputed rocks in the South China Sea. A former Australian ambassador to China recently wrote that China’s sway in the country extends to “surveillance, direction and at times coercion” of Chinese students and attempts to enlist Australian Han businessmen to causes serving China’s interests. Chinese-language media in Australia, which was almost universally critical of China in the early 1990s, is mostly positive today and eschews sensitive topics such as Tibet and Falun Gong.

China struggles to accept that descendants of Chinese emigrants may feel no obligation to reflect China’s interests. Gary Locke, the first Chinese-American ambassador to Beijing in 2011-14, was repeatedly criticised by state media for doing his job—representing American interests, even if they conflicted with China’s. Foreign Han journalists in China report accusations of disloyalty by the Public Security Bureau and reminders of their “Chinese blood”.

There is a strong ethnic component to China’s tense relationship with Hong Kong (which it rules) and Taiwan (which it claims). Each is dominated by Han, but increasingly they prize a local rather than “Chinese” identity. A poll by the Chinese University of Hong Kong found that 9% of respondents identified themselves solely as “Chinese”, down from 32% in 1997, when the territory returned to Chinese rule; the trend is similar in Taiwan.

The Peking order

The Chinese government even risks clashing with foreign governments by claiming some form of jurisdiction over their ethnic-Han citizens. Last year the government of Malaysia (where the Han population is 25%) censured the Chinese ambassador when he declared that China “would not sit idly by” if its “national interests” and the “interests of Chinese citizens” were violated. The threat he saw was a potentially violent pro-Malay rally, planned in an area where almost all traders were Han but few were Chinese nationals. In isolated cases it goes further. The arrest and detention of naturalised American citizens born in China has long been an irritant in relations between the countries.

China’s Han-centred worldview extends to refugees. In a series of conflicts since 2009 between ethnic militias and government forces in Myanmar the Chinese government has consistently done more to help the thousands escaping into China from Kokang in Myanmar, where 90% of the population is Han, than it has to aid those leaving Kachin, who are not Han. Non-Chinese seem just as beguiled by the purity of Han China as the government in Beijing. Governments and NGOs never suggest that China take refugees from trouble spots elsewhere in the world. The only large influx China has accepted since 1949 were also Han: some 300,000 Vietnamese fled across the border in 1978-79, fearing persecution for being “Chinese”. China has almost completely closed its doors to any others. Aside from the group from Vietnam, China has only 583 refugees on its books. The country has more billionaires.

China’s iron immigration and refugee policy attracts little attention probably because few have sought to immigrate. Victor Ochoa from Venezuela describes himself as “red-diaper baby”, the child of foreign experts who went to China in the 1960s to help build a Socialist Utopia. He studied architecture in Beijing and has remained in China. Yet he has had to apply for a work visa annually for 40 years to stay; now he wants to retire, he has no means to stay: “I’ve built hospitals here, now I just want to sit in my apartment and read. But I am not allowed,” he laments.

Uighurs, keep your beards trimmedMany outsiders see China as a land of opportunity. Some seek to settle. Yet the government is becoming more draconian towards such groups. Tens of thousands of Chinese men have undocumented marriages with women from Vietnam, Myanmar and Laos, often of the same (non-Han) ethnic group. After years of officialdom turning a blind eye, many of these women are now being sent back and their ID cards confiscated. Guangzhou’s government has launched a three-year plan to tackle illegal immigration. It named no target but may have its eye on up to 500,000 Africans, many of them overstaying their visas, in part of Guangzhou known by locals as “Chocolate City”.

Uighurs, keep your beards trimmedMany outsiders see China as a land of opportunity. Some seek to settle. Yet the government is becoming more draconian towards such groups. Tens of thousands of Chinese men have undocumented marriages with women from Vietnam, Myanmar and Laos, often of the same (non-Han) ethnic group. After years of officialdom turning a blind eye, many of these women are now being sent back and their ID cards confiscated. Guangzhou’s government has launched a three-year plan to tackle illegal immigration. It named no target but may have its eye on up to 500,000 Africans, many of them overstaying their visas, in part of Guangzhou known by locals as “Chocolate City”.

Decades ago China’s government might have argued that the country was too populous or too poor to accept new entrants. Now Chinese women have fewer than 1.6 children on average, well below the replacement rate, and in 2012 the working-age population shrunk for the first time. Yet China is already succumbing to problems many countries face as they grow richer and their workforce better educated. It has a severe shortage of social workers, care staff and nurses, jobs that most Chinese are unwilling to fill. That deficit will grow over the next decade as China’s population ages. Most rich countries attract immigrants to perform such roles, yet in September China’s government reiterated that visas for unskilled or service-industry workers would be “strictly limited”.

A closed China wilfully narrows its access to the global pool of professional talent. The government grants surprisingly few work visas. Foreigners made up 0.05% of the population in 2010, according to the World Bank, compared with 13% in America. A “green card” scheme was launched over a decade ago to attract overseas talent but only around 8,000 people qualified for one before 2013, the latest date for which figures exist. Many of these were former citizens with overseas passports, says Wang Huiyao of the Centre for China and Globalisation, a think-tank in Beijing.

Land of silk and money

At the same time its own citizens are heading overseas. Hundreds of thousands of Chinese leave every year to study or work abroad. Many have returned to China to work and are a driving force of innovation and high-tech development. Far more do not come back: of the 4m Chinese who have left to study abroad since 1978, half have not returned, according to the Ministry of Education. Yet because China bans dual nationality those who become eligible for a foreign passport, by birth, wealth or residency, face a choice. The result is that the brain-drain is mostly one-way. Thousands of Chinese renounce their citizenship every year, but because it is so difficult for foreigners to become Chinese, no counterbalancing group opts in.

China’s Han-centred worldview is not just a historical curiosity. It is a decisive force in the way it wields its growing power in the world—a state that respects neither equality nor civil liberties at home and may ignore them abroad too. In economic terms, China will cut itself off from an important source of economic growth, waste resources in discriminating against ethnic minorities and fail to use its human talent to better effect. Exacerbating ethnic tensions may spur the separatism it fears. And by sorting citizens abroad by their ethnic identity rather than their national one—whether by claiming to defend “its own” or punish them for disloyalty—China risks clashing with other countries. Over the past century, China’s founding myth has been a source of strength. But as it looks forwards, China risks being borne back ceaselessly into its own past.

No comments:

Post a Comment