WITH the giant Himalayas caging its towering clouds, the great basin where the Brahmaputra merges with the Ganges and Meghna rivers is prone not only to heavy rainfall but also to sudden deluges. Bits of the Indian state of Meghalaya receive over 11 metres (36 feet) of rain a year, making them the wettest places on the planet. Where there is so much water plus so many people—the basin, which covers just 1% of the world’s land area, is home to one in ten of its people—flooding is a perpetual hazard. In the thickening heat of every summer the locals greet the monsoon with both relief and trepidation.

WITH the giant Himalayas caging its towering clouds, the great basin where the Brahmaputra merges with the Ganges and Meghna rivers is prone not only to heavy rainfall but also to sudden deluges. Bits of the Indian state of Meghalaya receive over 11 metres (36 feet) of rain a year, making them the wettest places on the planet. Where there is so much water plus so many people—the basin, which covers just 1% of the world’s land area, is home to one in ten of its people—flooding is a perpetual hazard. In the thickening heat of every summer the locals greet the monsoon with both relief and trepidation.

This year’s monsoon has seen as many as 1,000 Indians killed in floods, half of them in the country’s poorest state, Bihar, where 12m people may have abandoned their homes. On August 29th 33cm of rain practically shut down Mumbai; on the 31st a building there collapsed.

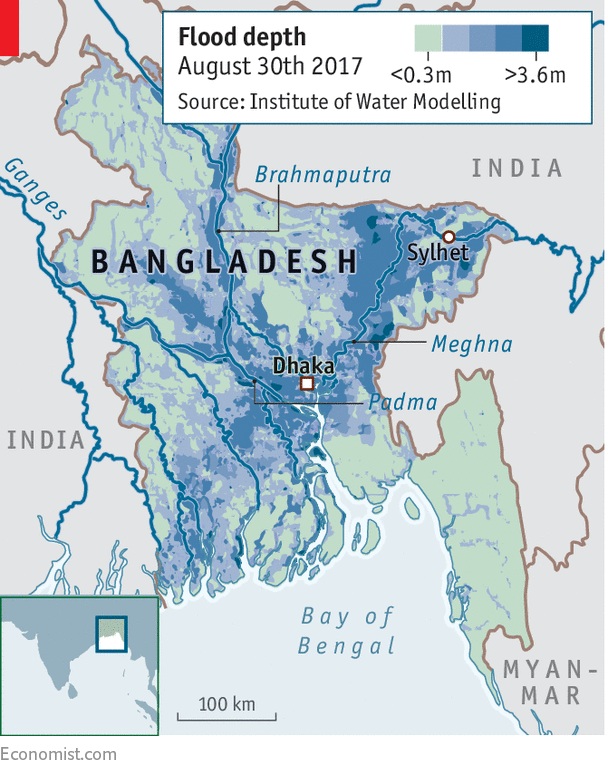

In neighbouring Bangladesh, flooding killed more than 144 in August, with some 11m people affected. As much as a third of the country was briefly submerged when waters peaked late in the month. A similar number lost their lives in Nepal.

The region has seen worse. In 2007 floods killed 3,300 people in India and Bangladesh. In 2010 flooding killed 2,100 people in Pakistan, and in 2013 some 6,500 people died due to floods in India. Bangladesh saw catastrophic floods in 1974, 1987, 1988 and 1998, when the capital city, Dhaka, was inundated. In July 2005 Mumbai received almost a metre of rainfall in a single 24-hour period.

But the death toll in this year’s floods is still high—even though, according to the Indian Meteorological Department (IMD), this summer has been no wetter than the long-term average for rain across northern India. Despite floods in Assam in April, in Gujarat in July, in Bihar in August and most recently in Mumbai, this monsoon’s rainfall is still some 3% below average.

This contrast is part of a pattern. In recent decades the volume of rain brought by the monsoon (which in a typical year provides 85% of all India’s rainfall) has declined; this year’s slightly sub-par affair is being greeted across most of the subcontinent as a welcome return to form after a couple of dry years. At the same time the incidence of short periods of sudden, torrential rain has been increasing, particularly in July and August. A paper published in Nature Climate Change in 2014 by researchers at Stanford states that the intensity of extremely wet spells and the frequency of extremely dry spells during the South Asian monsoon season have been increasing since 1980. “We are looking at rainfall extremes that only occur at most a few times a year, but can have very large impact,” says Noah Diffenbaugh of the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment.

His team found that central India’s average July and August rainfall has fallen from 1cm a day to about 0.9cm a day over the past 60 years. However its day-to-day variability has increased. At some level, these stronger rains may be compensating for an overall weakening of the monsoon.

Pushed to extremes

Pushed to extremes

In Bangladesh, this year’s floods are the most extensive since 1998, when two-thirds of the country was inundated, over 1,000 people died and 30m were affected. More than half a million houses have been destroyed; the overflowing Brahmaputra, locally known as the Jamuna, has washed away embankments and cut train links. Over 6,000 square kilometres of standing crops have been damaged, and farmers in the north of the country will not be able to replant their paddies. (As ever, Dhaka’s politicians have accused India of not giving them enough notice before releasing floodwater down the more than 50 rivers that flow from India to Bangladesh.)

But loss of life has been limited, in part because of investments in risk management. The defences around Dhaka have held, though the city’s Flood Forecasting and Warning Centre says the level of the Brahmaputra is still threatening embankments south of the capital. Forecasting has improved. Text messages are now used to warn of disasters. The days when cyclones would leave hundreds of thousands dead seem now to be in the past.

The government is providing food assistance to 2.8m people. Sheikh Hasina, the prime minister, has reassured the public that there will be enough food. That she had to say so was disquieting. In usually food-self-sufficient Bangladesh, which is the world’s fourth-largest rice producer, stocks are depleted. An earlier, unseasonal flood ruined rice crops in north-eastern Sylhet and sent rice prices spiralling.To limit the political fallout, the government cut the duty on rice imports from 28% to 2% and ordered 1.5m tonnes from overseas. That should succour the displaced as they watch the monsoon tail off and the waters recede—and start to prepare for the challenges of the next year.

No comments:

Post a Comment