THE faithful are returning from the haj. Waiting for prayers outside the Great Mosque in Tongxin, a remote town in the western province of Ningxia, Li Yuchuan calls his pilgrimage a liberation: “Our prayers are just homework for it.” His 84-year-old friend (pictured, right) leaps up and twists himself with lithe agility into the shape of a pretzel. “We Muslims pray five times a day,” he says. “We are flexible and tough.” China’s Muslims need to be.

THE faithful are returning from the haj. Waiting for prayers outside the Great Mosque in Tongxin, a remote town in the western province of Ningxia, Li Yuchuan calls his pilgrimage a liberation: “Our prayers are just homework for it.” His 84-year-old friend (pictured, right) leaps up and twists himself with lithe agility into the shape of a pretzel. “We Muslims pray five times a day,” he says. “We are flexible and tough.” China’s Muslims need to be.

China has a richly deserved reputation for religious intolerance. Buddhists in Tibet, Muslims in the far western region of Xinjiang and Christians in Zhejiang province on the coast have all been harassed or arrested and their places of worship vandalised. In Xinjiang the government seems to equate Islam with terrorism. Women there have been ordered not to wear veils on their faces. Muslims in official positions have been forced to break the Ramadan fast. But there is a remarkable exception to this grim picture of repression: the Hui.

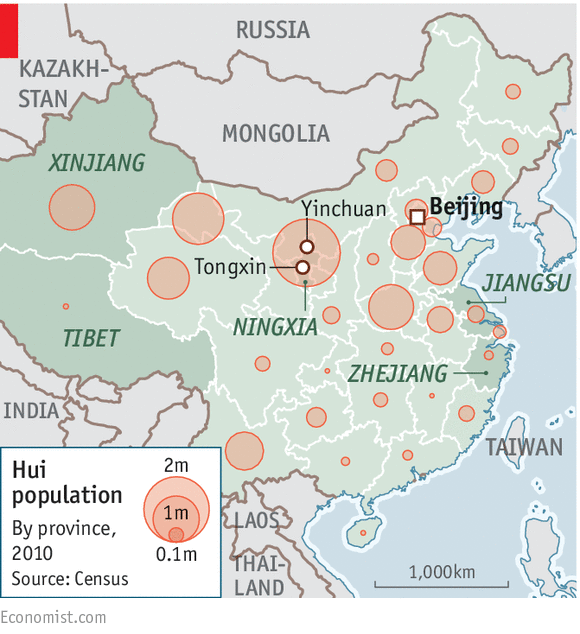

China has two big Muslim groups, the Uighur of Xinjiang and the more obscure Hui. Though drops in the ocean of China’s population, they each have about 10m people, the size of Tunisia. But while the Uighur suffer, the Hui are thriving.

The number of mosques in Ningxia (cradle of the Hui, as one of their number puts it) has more than doubled since 1958, from 1,900 to 4,000, says Ma Ping, a retired professor at Northern Nationalities University. New ones are being built across the province. The Hui are economically successful. They are rarely victims of Islamophobia. Few Muslim minorities anywhere in the world can say as much.

The Hui’s religious practices reflect the waves of Islam that have washed over China. According to Ma Tong, a Hui scholar, just over half of them follow the Hanafi school of Sunni Islam, which was brought to China centuries ago. At the Najiahu mosque south of Yinchuan, Ningxia’s capital, banners adorn the entrance saying “ancient and authentic religion” and “cleave to the original path”. A fifth of the Hui follow the more austere code of Wahhabism brought to China in the 19th century (there are also a handful of more extreme Salafist converts resulting from recent contacts through the haj). And a fifth follow one of three Sufi schools of Islam, an esoteric and mystical branch derided as apostate by hardline Salafists. The Hui’s religious diversity makes it easier for the party to tolerate them. Divide and rule.

But the real secret of the Hui’s success lies in the ways they differ from the Uighur. The Uighur, of Turkic origin, are ethnically distinct. They speak their own language, related to Turkish and Uzbek. They have a homeland: the vast majority live in Xinjiang. A wall of discrimination separates them from the Han Chinese. If they have jobs in state-owned enterprises, they are usually menial.

In contrast, the Hui are counted as an ethnic minority only because it says so on their hukou (household-registration) documents and because centuries ago their ancestors came as missionaries and merchants from Persia, the Mongol courts or South-East Asia. Having intermarried with the Han for generations, they look and speak Chinese. They are scattered throughout China (see map); only one-fifth live in Ningxia. Unlike the Uighur and Tibetans, they have taken the path of assimilation.

At the new Qiao Nan mosque in Tongxin, the congregation is celebrating the life of an important local figure in the mosque’s history. The ceremony begins with a sermon by the ahong (imam). Then come prayers chanted in Arabic. At the house of the local worthy’s grandson, the worshippers read from the Koran, then visit the tomb. But the afternoon ends very differently, with a reading from an 18-metre-long scroll written by the grandson, Ma Jinlong. This consists of excerpts from eighth-century classical Chinese poetry, illustrated with his own delicate water-colours. Mr Ma is both a stalwart of the mosque and a Chinese gentleman-scholar.

A close connection with Chinese society is characteristic of the Hui. Some of the most famous historical figures were Hui, though few Chinese are aware of it. They include Zheng He, China’s equivalent of Columbus, who commanded voyages of discovery around 1400. Recently, the party chief in Jiangsu province as well as the head of the Ethnic Affairs Commission, a government body, were Hui.

Relations with the Han have not always been good. The so-called Dungan revolt by the Hui in the 1860s and 1870s was a bloodbath. But since the death of Mao in 1976, the two sides have reached an accommodation. Dru Gladney, of Pomona College in California, says a hallmark of the Hui is their skill at negotiating around the grey areas of China’s political system.

Thanks to this, they have been successful economically. They dominate halal food production (see article). They are emerging as the favoured middlemen between China’s state enterprises and firms in Central Asia and the Gulf. China’s largest school of Arabic is a private college, set up and partly financed by Hui, on the outskirts of Yinchuan. Most students are training to be corporate interpreters.

One sign of how far the government tolerates the Hui is that they are even able to practice Islamic (sharia) law to a limited extent. Sharia is not recognised by the Chinese legal code. Yet at the Najiahu mosque, the ahong and the local county court share the same mediation office. Every week or so, the ahong adjudicates in family disputes using sharia. Only if he fails do civil officials step in.

Surprisingly, the Hui have not lost their religion or identity despite centuries of assimilation. Mr Ma, the retired professor, says Hui people often form close-knit communities and pursue similar occupations; restaurants and taxis in many cities are run by Hui. But their religion is “still the most important binding factor”, he says. The Hui maintain a delicate balance. They can practise their religion undisturbed thanks to assimilation. But it is their religion that makes them distinct.

This is a fine line, and it means the Hui are vulnerable to China’s shifting religious attitudes. They have so far mostly escaped Islamophobia. But bigotry is becoming more common on social media. “The greens” (a significant colour in Islam) has become an online term of abuse. So far the government has tolerated the Hui’s culture. But in Ningxia in July, Xi Jinping, the president, told his audience to “resolutely guard against illegal infiltration”—even though there is little sign of any. His government has become more repressive towards many religious groups. The Hui could be next.

But the lessons offered by the Hui’s experience are largely positive. Islam, the Hui show, are not the threat that party leaders sometimes imply it is. They show that you can be both Chinese and Muslim. At Yinchuan airport, a returning pilgrim is waiting for his luggage. He wears a white robe with “Chinese pilgrimage to Mecca” stitched in green Arabic letters below a Chinese flag embroidered in red, the symbol of an atheist party-state. “It was the experience of a lifetime,” he says of the haj—and disappears into a sea of white hats worn by hundreds of cheering fellow Muslims who fill the arrivals hall to welcome him home.

No comments:

Post a Comment