“DEAD, dying or detained.” That is how a member of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt describes the state of his comrades in what was once the world’s pre-eminent Islamist movement. After the Arab spring of 2011 the Brotherhood won Egypt’s first free elections; by early 2012 it ruled the country. But the army, led by Abdel-Fattah al-Sisi and backed by mass protests, soon booted it from power. Four years ago this month Mr Sisi, now the president, crushed the movement in Rabaa al-Adawiya square (pictured). Today those not dead or in jail have fled or hidden.

“DEAD, dying or detained.” That is how a member of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt describes the state of his comrades in what was once the world’s pre-eminent Islamist movement. After the Arab spring of 2011 the Brotherhood won Egypt’s first free elections; by early 2012 it ruled the country. But the army, led by Abdel-Fattah al-Sisi and backed by mass protests, soon booted it from power. Four years ago this month Mr Sisi, now the president, crushed the movement in Rabaa al-Adawiya square (pictured). Today those not dead or in jail have fled or hidden.

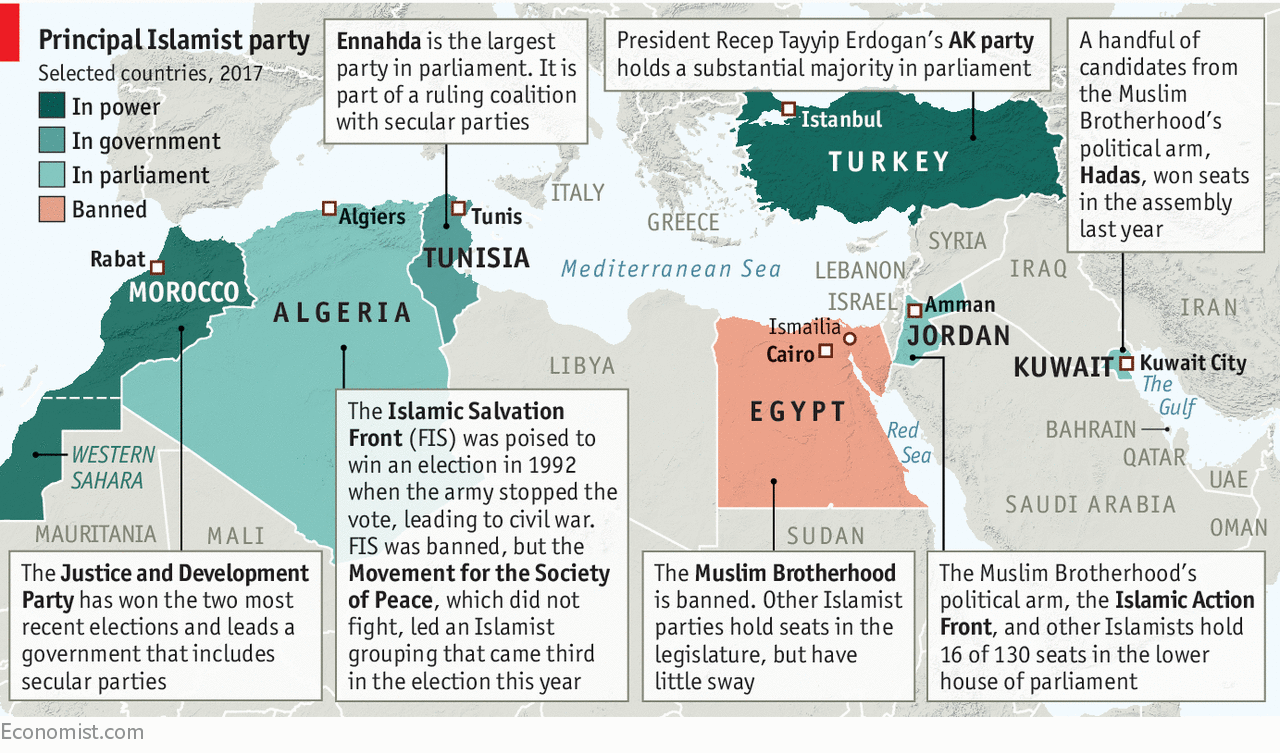

Yet the Brotherhood, a transnational movement that has spawned many other Islamist parties in the region, still inspires fear in Arab autocrats. For proof, look no further than the standoff over Qatar. Egypt, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain have cut off diplomatic and transport links with the tiny gas-rich sheikhdom, demanding that it end its support for the Brotherhood; shut down Al Jazeera, a Brotherhood-friendly broadcaster; and kick out troops from Turkey, which is led by a Brotherhood-inspired party, Justice and Development (AK). They insist that the Brotherhood is a terrorist organisation which threatens to up-end the established order.

That the Brotherhood has inspired violence and that its members have carried out attacks is not in doubt; whether it is essentially violent is harder to say. Hassan al-Banna, who founded the movement in Ismailia, in north-east Egypt, in 1928, called for gradual reform, but he accommodated militant members. Sayyid Qutb, a leading figure in the Brotherhood in the 1950s and 1960s, favoured taking up arms against impious rulers. Modern Islamism—broadly defined as the pursuit of a state governed by Islamic principles—grew out of this debate in various directions. Its current incarnations and hybridisations include groups as diverse as Ennahda, a peaceful Tunisian political party, and Islamic State (IS), a violent jihadist group that calls the Brothers apostates. Today’s Egyptian Brotherhood is split between those who embrace confrontational tactics, including some who countenance violence, and those who favour a more conciliatory approach.

The Saudis and the other countries leaning on Qatar claim that the whole Islamist spectrum is beyond the pale. (Though some have made tactical common cause with Islamists in Palestine, Yemen and Syria.) Others—including Western governments that have resisted calls to brand the Brotherhood a terrorist organisation—think there are distinctions worth making. This is not easily done. When elected, ostensibly moderate and democratic Islamists have too often proved to be neither, lending credence to the argument that their commitment to democracy goes little further than “one man, one vote, one time.” But some Islamists are participating in politics, and even leading governments, moderately and effectively.

Islamists are hardly alone in attempting to inject religion into public life. In India the ruling BJP espouses a specifically Hindu nationalism. Israel has a range of parties seeking to create a more overtly Jewish state. Europe has many Christian Democrats who take both parts of the name seriously. In America the Republican Party’s platform holds that if “God-given, natural, inalienable rights” conflict with “government, court, or human-granted rights”, the former must always prevail. “They are saying something on which all Islamists could agree,” says Nathan Brown of George Washington University.

In the beginning

Islam is unique, though, in at least one regard. Whereas Moses was a leader without a state and Jesus was a dissident executed by one, the Prophet Muhammad was a political leader who founded a polity, and Muslim scripture reflects that. “In the Koran, there are clear, direct textual injunctions ranging from the implementation of the hudud punishments [for offences such as theft] to specific rules on inheritance,” writes Shadi Hamid of the Brookings Institution, a think-tank, in “Islamic Exceptionalism”. Hence the Brotherhood’s proud claim that “the Koran is our constitution”.

But although the Koran may have specific things to say about inheritance and other matters, it is more fuzzy on how to organise government. In one sura Muhammad is instructed to consult members of the community; in another he is given absolute power over them. Disagreements started immediately upon the prophet’s death. His closest followers could not decide if the role of caliph—the presumed successor to Muhammad as leader—should be elective or hereditary, a dispute that eventually led to the schism between, respectively, Sunnis and Shias.

The caliphate itself is not mandated by the Koran. But “traditional Muslim thought regarded [it] as an inherent part of Islam, unintentionally politicising the faith for centuries,” writes Mustafa Akyol, the author of “Islam without Extremes”. Hereditary caliphates in which religious and secular power were united in one figure were the model for Islamic polities for more than a millennium.

It was the break-up of the Ottoman empire and the abolition of the caliphate by republican Turkey that ultimately led to the modern-day Islamist movement. Muslims humiliated by colonialism and the failures of socialism and nationalism, under which home-grown autocrats tried to co-opt Islam for their own benefit, longed for an alternative that made sense in a world of nation-states and elections. The Brotherhood presented them with one.

Democracy was not one of Muhammad’s prescriptions, so Banna rejected it as a foreign import, along with political parties and even the modern Arab state. But he also saw progress towards the Islamic state happening in stages, each requiring different tactics. So Islamists might play down their divine objective early on, and even participate in elections, if it improved their position in the long term. Some of his followers came to accept democracy as part of all stages of the process; but critics held that most Islamists were at heart anti-democratic and continue so to be.

That is one lens through which to view AK and its imposing leader, Recep Tayyip Erdogan. When Mr Erdogan founded AK in 2001 he appeared to represent a new kind of Islamism, what some called “Islamism-lite”, that focused on freedom and free markets. After winning legislative elections for the first time in 2002, the party pushed through democratic reforms, subdued Turkey’s army and strengthened the state’s recognition of human rights. It was held up as a hopeful template for other Islamist parties.

Gradually, though, Mr Erdogan concentrated power in his hands. He co-opted the state-run media and ousted critics in the government, army and judiciary. More liberal members of AK, such as Abdullah Gul, a former president, were pushed aside. An unsuccessful coup in July 2016 led to an all-out purge. Tens of thousands of enemies, real and imagined, were arrested, including journalists. Civil-society groups were shut down, civil servants sacked, access to parts of the internet blocked. In April a referendum on the constitution (which critics claim was rigged) gave the president even more power.

Turkey is exhibit B for those making the case against seemingly moderate Islamists. Egypt is exhibit A. Muhammad Morsi, the Brotherhood figure who became president, proved divisive and insular from the start. By the end of his first year he had decreed that he was not bound by judicial restraints. He pushed through a constitution that was opposed by secular politicians and flooded the government with Islamists. By the time of the coup against him much of the public was on the army’s side.

Some now argue that these outcomes—illiberal success in Turkey, illiberal failure in Egypt—were foreseeable, even inevitable. But it is worth looking at the contexts. Before AK came on the scene in Turkey, four previous Islamist parties had been closed as a result either of a coup or a court order. After AK came to power it continued to be threatened. Secularists in the army—part of the country’s “deep state”—tried to block the party’s presidential candidate in 2007. A year later, Turkey’s chief prosecutor accused AK of being anti-secular and came close to having it banned. There was a host of other politically motivated attacks—and then there was the coup attempt.

In Egypt the Brotherhood faced similar opposition from a deep state of soldiers, judges and bureaucrats. The police refused to patrol the streets, leading to a spike in crime. Employees of the gas and power companies created artificial blackouts and fuel shortages. Judges appointed by Mr Morsi’s predecessor declared the results of an election invalid.

Minorities retort

These challenges do not excuse the authoritarianism displayed by Mr Morsi and Mr Erdogan. But perhaps they explain it better than notions of an illiberal essence in their ideology. “Islamist parties tend to adapt to their political environment,” says Marc Lynch of George Washington University. The fear that secularists would try to undermine their governments convinced elected Islamists that they needed to grab as much power as possible; the lack of deep-seated democratic traditions made things worse. The problem with AK, says Mr Akyol, is not that it has been too Islamist: “It is just proving to be too Turkish.”

Elsewhere, Islamist parties have continued to take part in elections. The Brotherhood’s chapters in Jordan and Kuwait, after suffering years of repression, did relatively well in parliamentary elections last year. A Brotherhood spin-off, the Party of Justice and Democracy (PJD), has won Morocco’s two most recent parliamentary elections and leads the current government. Outside the Brotherhood’s orbit, Islamist parties are politically active in Indonesia, Malaysia and Pakistan. The idea that all such parties are playing Banna’s long game cannot be disproved. But it is at least plausible that, in environments that do not encourage authoritarianism, it is not a necessary development. In nearly all the places where Islamists are politically active, there are checks on how much power they can amass. Monarchs are the real authority in Morocco, Jordan and Kuwait.

That said, Islamists do not have to win national elections to have an illiberal impact. In Indonesia, a secular democracy, no avowedly religious party has ever received more than 8% of the vote in national parliamentary elections even though the country is majority Muslim. But locally elected Islamists have passed over 400 local ordinances based on Islamic law since the country’s regions were granted more autonomy in 1999. In Aceh province alcohol is prohibited, women’s dress is restricted and adultery and homosexuality are punished with whippings.

Perhaps the most troubling sign of the Islamist minority’s power came in April, when a popular Christian incumbent, Basuki Tjahaja Purnama, better known as Ahok, lost the governor’s race in Jakarta. Islamist supporters of his opponent, Anies Baswedan, told Muslim voters that it was haram (forbidden under Islam) to vote for a Christian. When Ahok tried to argue against this claim, citing the Koran, a doctored video made it seem as if he was disparaging the holy book. He was charged with blasphemy, lost the election and has now been sentenced to jail.

Indonesia thus shows how the workings of democracy can magnify the power of an illiberal minority. A survey conducted in 2015 by the Centre for the Study of Islam and Society, a think-tank in Jakarta, found that the proliferation of sharia-based ordinances was largely the result of local politicians acceding to the demands of conservative Muslim groups in exchange for votes. Once God’s law is enacted, it proves hard for man to rescind. In Aceh a substantial portion of the public has misgivings about sharia. But none of the major candidates in the elections last spring challenged the recent sharia strictures for fear of being ostracised.

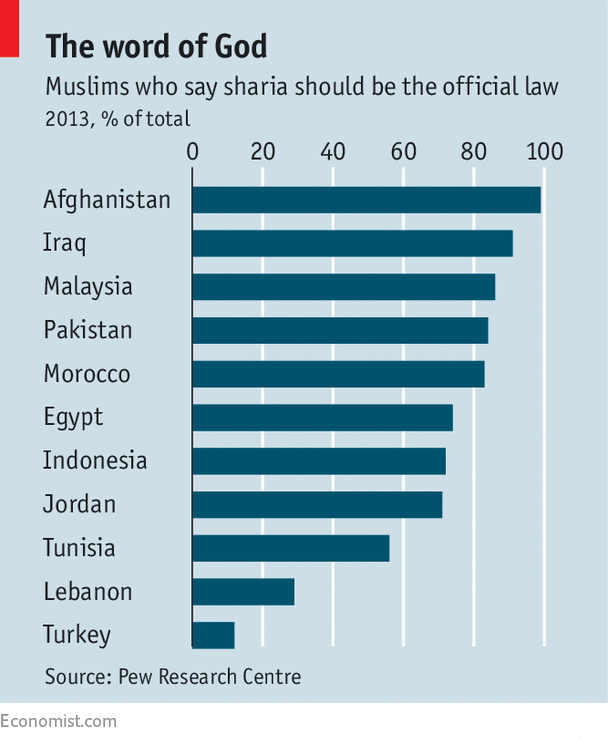

Support for Islamist legislation, regardless of which parties provide it, is widespread in Islamic countries (see chart). In Egypt polls show that majorities back legal codes based on sharia, punishments from the Koran and giving clerics the power to draft legislation. But this is not a strong feature of AK rule in Turkey. The party has built more mosques and opened religious schools, restricted alcohol sales and lifted bans on the hijab. But it has not banned alcohol or imposed restrictions on dress. In fact the party has often seemed more interested in using Islam in the service of politics, rather than the other way around.

Support for Islamist legislation, regardless of which parties provide it, is widespread in Islamic countries (see chart). In Egypt polls show that majorities back legal codes based on sharia, punishments from the Koran and giving clerics the power to draft legislation. But this is not a strong feature of AK rule in Turkey. The party has built more mosques and opened religious schools, restricted alcohol sales and lifted bans on the hijab. But it has not banned alcohol or imposed restrictions on dress. In fact the party has often seemed more interested in using Islam in the service of politics, rather than the other way around.

It is unsettling for liberals to know that, even in the minority, Islamists can ratchet up restrictions. But that is, in the end, the sort of risk democracies of all stamps live with—and which, if the democracies are strong, can be fought. Hence the belief of some analysts that elections, not liberalism, matter most: illiberal democracy, they say, is a precursor to liberal democracy. In previously authoritarian countries democracy must be given time to take root and be strengthened through practice. The secularists trying to force the Brotherhood from power in Egypt in 2013 heard such arguments often. Anything Mr Morsi did, the plea went, could be undone by more secular governments in the future.

The new model

Taking that seriously means believing that Islamists will continue to hold elections when in power. Here the poster child is Tunisia. Many members of Ennahda dream of creating an Islamic state in the country, replete with sharia. But on the whole, the movement founded and still led by Rachid Ghannouchi has displayed moderation and a rare willingness to compromise.

Ennahda suffered under the decades-long secular dictatorship of Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali, who banned the movement. After Mr Ben Ali was overthrown in 2011, a party created by the movement won a plurality of seats in Tunisia’s first free elections. But it faltered in government, alienating Tunisians, many of whom were sceptical of the Islamists. It did not help that ultraconservative Muslims assassinated two left-wing politicians in 2013.

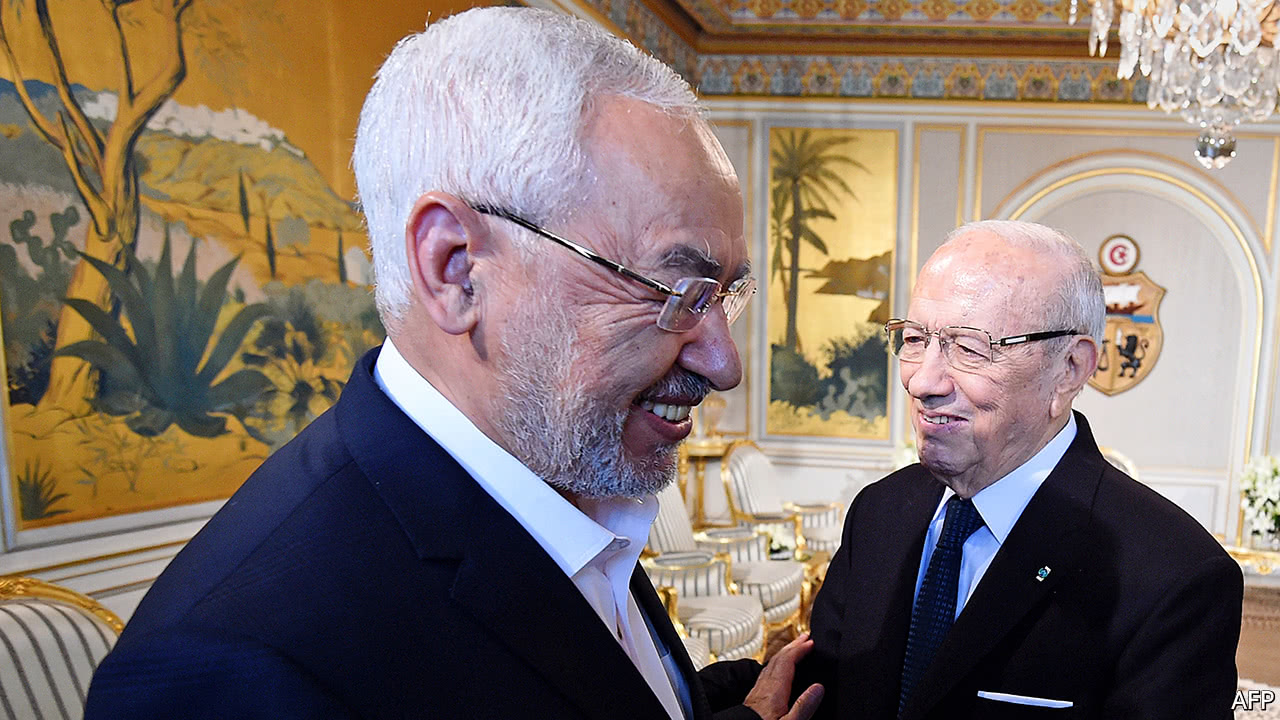

Opposition to Ennahda rule culminated in street protests that threatened to undo the country’s fragile democratic gains. But instead of digging in, as the Brotherhood did in Egypt, Ennahda chose to yield ground (especially after the coup in Egypt). In negotiations over a new constitution it accepted liberal recommendations, such as guaranteed freedom of religion. After parliament passed the charter—its members chanting “mabrouk aleina” (congratulations to us all)—Ennahda handed power to a technocratic government in January 2014. Ennahda lost the next election to Nidaa Tounes, a secularist party created specifically to defeat the Islamists. Mr Ghannouchi promptly struck up an alliance (and friendship) with Beji Caid Essebsi, the new party’s founder. Since then Nidaa Tounes has split; but Ennahda has not pressed its advantage as the biggest party in parliament. “In this transitional situation, what we need is broad consensus,” says Mr Ghannouchi. A Brotherhood member in Egypt puts it another way: “They learned from our mistakes.”

Mr Ghannouchi now says Ennahda is not an Islamist party, but a party of “Muslim Democrats”, akin to European Christian Democratic parties. The movement has split its political party from its religious arm, which is now solely responsible for dawah (proselytising and preaching). Its politicians cannot give speeches in mosques; clerics cannot lead the party. Ennahda still draws on Islam for inspiration, says Mr Ghannouchi, but “the presence of religion [in society] is not something that is decided or set by the state.” It should be a “bottom-up phenomenon” and, with an elected parliament, “to the extent that religion is represented in society, then it is also represented in the state.”

Secularists and liberals have long hoped that mainstream Islamists would follow such a path. In essence what they are hoping for is that Islamists, long a movement of protest, become less Islamist when confronted with the reality of power. That raises other questions. “If Islamist parties, once elected, have to give up their Islamism...then this runs counter to the essence of democracy—the notion that governments should be responsive to, or at least accommodate, public preferences,” writes Mr Hamid.

More conservative members of Ennahda are unhappy with the direction that the movement has taken. Others doubt Ennahda’s bona fides, claiming that fear of repression and revolt is the motivating factor behind its moderation—in other words, that its actions are tactical. “We get it from all sides,” says Mr Ghannouchi.

As with Islamism’s downfall in Egypt, its happier progress in Tunisia is, in large part, a matter of context. Unlike Egypt and Turkey, Tunisia does not have a strong and politicised army. And whereas the state’s repression in Egypt before the revolution seemed to harden the Brotherhood, in Tunisia it led Ennahda members, who shared prison cells with other opposition leaders, to adopt a more liberal worldview. The unique challenges faced in each country undoubtedly shaped their development. So Mr Ghannouchi says he has no desire to export the Ennahda model, seeing it as derived from the Tunisian context. “But if others find that they can benefit from our experience, that would make us happy.”

No comments:

Post a Comment