EVERY AFTERNOON AT sunset, at a point midway along the arrow-straight road between Amritsar and Lahore, rival squads of splendidly uniformed soldiers strut and stomp a 17th-century British military drill known as Beating Retreat (pictured). Barked commands, fierce glares and preposterously high kicks all signal violent intent. But then, lovingly and in unison, the enemies lower their national flags. Opposing guardsmen curtly shake hands, and the border gates roll shut for the night.

EVERY AFTERNOON AT sunset, at a point midway along the arrow-straight road between Amritsar and Lahore, rival squads of splendidly uniformed soldiers strut and stomp a 17th-century British military drill known as Beating Retreat (pictured). Barked commands, fierce glares and preposterously high kicks all signal violent intent. But then, lovingly and in unison, the enemies lower their national flags. Opposing guardsmen curtly shake hands, and the border gates roll shut for the night.

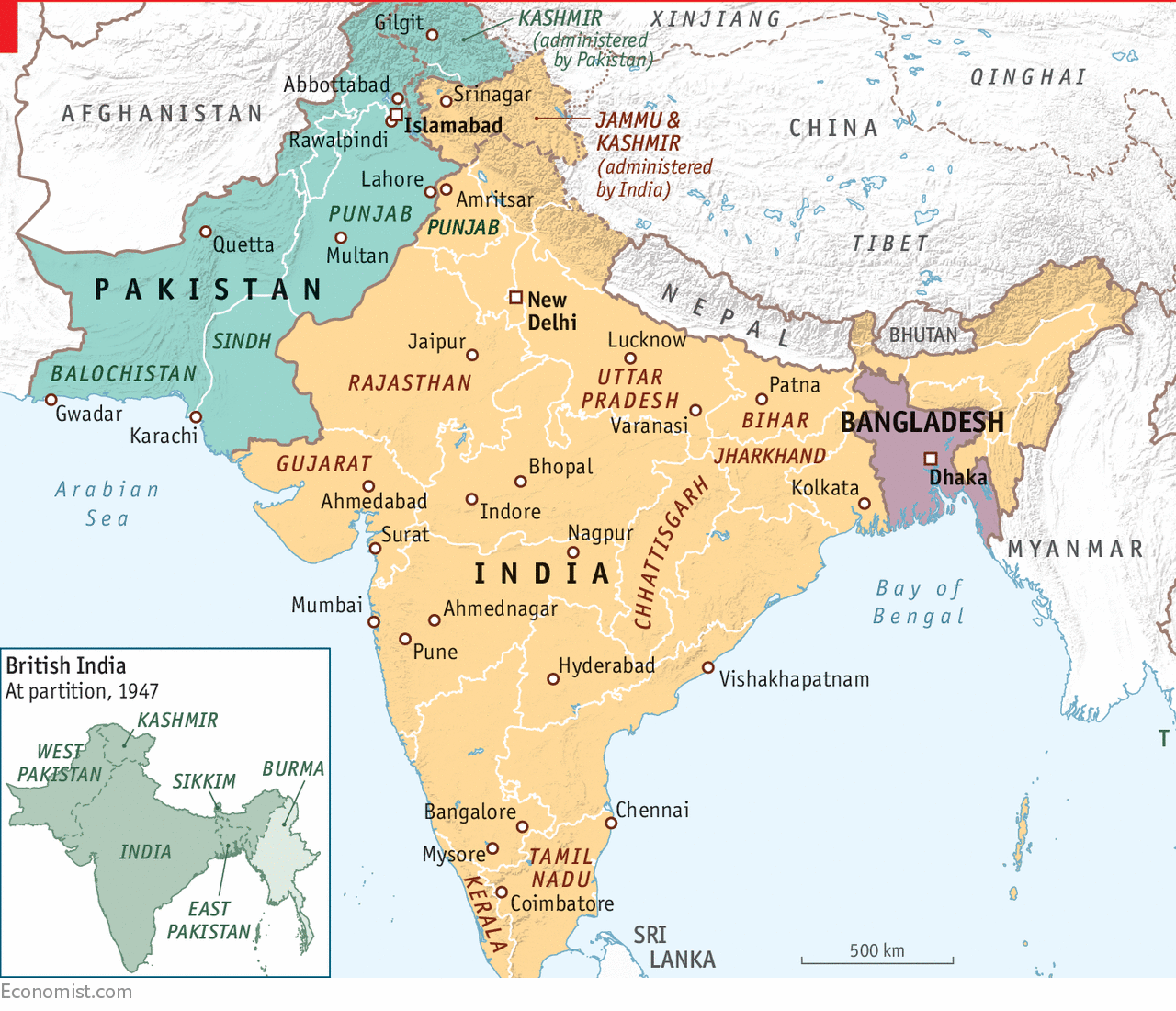

As India and Pakistan celebrate their twin 70th birthdays this August, the frontier post of Wagah reflects the profound dysfunction in their relations. On its side Pakistan has built a multi-tiered amphitheatre for the boisterous crowds that come to watch the show. The Indians, no less rowdy, have gone one better with a half-stadium for 15,000. But the number of travellers who actually cross the border here rarely exceeds a few hundred a week.

Wagah’s silly hats and walks serve a serious function. The cuckoo-clock regularity of the show; the choreographed complicity between the two sides; and the fact that the soldiers and crowds look, act and talk very much the same—all this has the reassuring feel of a sporting rivalry between teams. No matter how bad things get between us, the ritual seems to say, we know it is just a game. Alas, the game between India and Pakistan has often turned serious.

After the exhaustion of the second world war Britain was faced with two claimants to its restless Indian empire, a huge masala of ethnic, linguistic and religious groups (half of which was administered directly and half as “princely states” under 565 hereditary rulers subject to the British crown). Just about everyone wanted independence. But whereas the Congress Party of Mahatma Gandhi envisioned a unified federal state, the Muslim League of Muhammad Ali Jinnah argued that the subcontinent’s 30% Muslim minority constituted a separate nation that risked oppression under a Hindu majority. Communal riots prompted Britain’s last viceroy, Lord Mountbatten, to make a hasty decision. He split the country in two—or rather three, since the new state of Pakistan came in two parts, divided by the 2,000km (1,240-mile) expanse of the new state of India.

Latest updates

THE ECONOMIST EXPLAINS29 MINUTES AGO

GRAPHIC DETAIL13 HOURS AGO

DEMOCRACY IN AMERICA13 HOURS AGO

GULLIVER14 HOURS AGO

THE ECONOMIST EXPLAINSA DAY AGO

DEMOCRACY IN AMERICAA DAY AGO

When the two new states were proclaimed in mid-August 1947, it was hoped the partition would be orderly. Lines had been drawn on maps, and detailed lists of personnel and assets, down to the instruments in army bands, had been assigned to each side. But the plans immediately went awry in a vast, messy and violent exchange of populations that left at least 1m dead and 15m uprooted from their homes.

Within months a more formal war had erupted. It ended by tearing the former princely state of Kashmir in two, making its 750km-long portion of the border a perpetual subject of dispute. Twice more, in 1965 and 1971, India and Pakistan fought full-blown if mercifully brief wars. The second of those, with India supporting a guerrilla insurgency in the Bengali-speaking extremity of East Pakistan, gave rise to yet another proud new country, Bangladesh; but not before at least half a million civilians had died as West Pakistan brutally tried to put down the revolt.

Even periods of relative peace have not been especially peaceful. In the 1990s Pakistan backed a guerrilla insurgency in Indian Kashmir in which at least 40,000 people lost their lives. In 1999 Pakistani troops captured some mountain peaks in the Kargil region, which India clawed back in high-altitude battles. A ceasefire in Kashmir that has held since 2003 has not stopped Pakistan-sponsored groups from striking repeatedly inside India. Pakistan claims that India, too, has covertly sponsored subversive groups.

Analysts discern a pattern in this mutual harassment: whenever politicians on both sides inch towards peace, something nasty seems to happen. Typically, these cycles start with an attack on Indian soldiers in Kashmir by infiltrators from Pakistan, triggering Indian artillery strikes, which prod the Pakistanis to respond in kind. After a few weeks things will calm down.

Just such a cycle started in late 2015, prompted, perhaps, by a surprise visit to the home of the Pakistani prime minister, Nawaz Sharif, by his Indian counterpart, Narendra Modi. Hopes raised by this overture dimmed within days when jihadist infiltrators attacked an Indian airbase. Another suicide squad struck an Indian army camp near the border, killing 19 soldiers. Faced with public outrage, Mr Modi ordered a far harder response than usual, sending commando teams into Pakistan. In the past, India had kept quiet even when it hit back, leaving room for Pakistan to climb down. This time Mr Modi’s government moved to isolate Pakistan diplomatically, rebuffed behind-the-scenes efforts to calm tensions and sent unprovoked blasts of fire across the Kashmir border.

India’s loss of patience is understandable. It has a population six times Pakistan’s and an economy eight times as big, yet it finds itself being provoked far more often than it does the provoking. When Mr Modi’s Hindu-nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) came to power in 2014, it promised to put muscle into India’s traditionally limp foreign policy. “India for the first time is being proactive, not just responding,” says Sushant Singh, a military historian and journalist. “This is a huge shift.”

Yet Mr Modi’s pugnacity raises the risk of a dangerous escalation. “After a routine operation, the adversary may or may not escalate; after a publicised operation he will have only one option: to escalate,” writes Pratap Bhanu Mehta, one of India’s more thoughtful intellectuals.

Whether India and Pakistan are reckless enough to come to serious blows would not matter so much if they simply fielded conventional armies. But they are equipped with more than 100 nuclear warheads apiece, along with the missiles to deliver them. Since both countries revealed their nuclear hands in the 1990s, optimists who thought that a “balance of terror” would encourage them to be more moderate have been proved only partially right. Indians complain of being blackmailed: Pakistan knows that the risk of nuclear escalation stops its neighbours from responding more robustly to its provocations. Worryingly, Pakistan also rejects the nuclear doctrine of no first use. Instead, it has moved to deploy less powerful nuclear warheads as battlefield weapons, despite the risk that fallout from their use might harm its own civilians.

India does espouse a no-first-use nuclear doctrine, but its military planning is said to include a scenario of a massive conventional blitzkrieg aimed at seizing chunks of enemy territory and crushing Pakistan���s offensive capacity before it can respond. India’s arsenal includes the hypersonic Brahmos III, the world’s fastest cruise missile, which can precisely deliver a 300kg payload to any target in Pakistan. An air-launched version could reach Islamabad in two minutes, and Lahore in less than one. And in a grim calculation, India, with four times Pakistan’s territory, sees itself as better able to absorb a nuclear strike.

Alarmists will probably be proved wrong. Both countries are prone to sabre-rattling theatrics, but they are well aware that the price of full-blown war would be appalling. And despite the uncertainties generated by the rise of China, the continuing troubles in Afghanistan and the incalculability of Donald Trump’s America, the international community still seems likely to be able to pull Pakistan and India apart if need be.

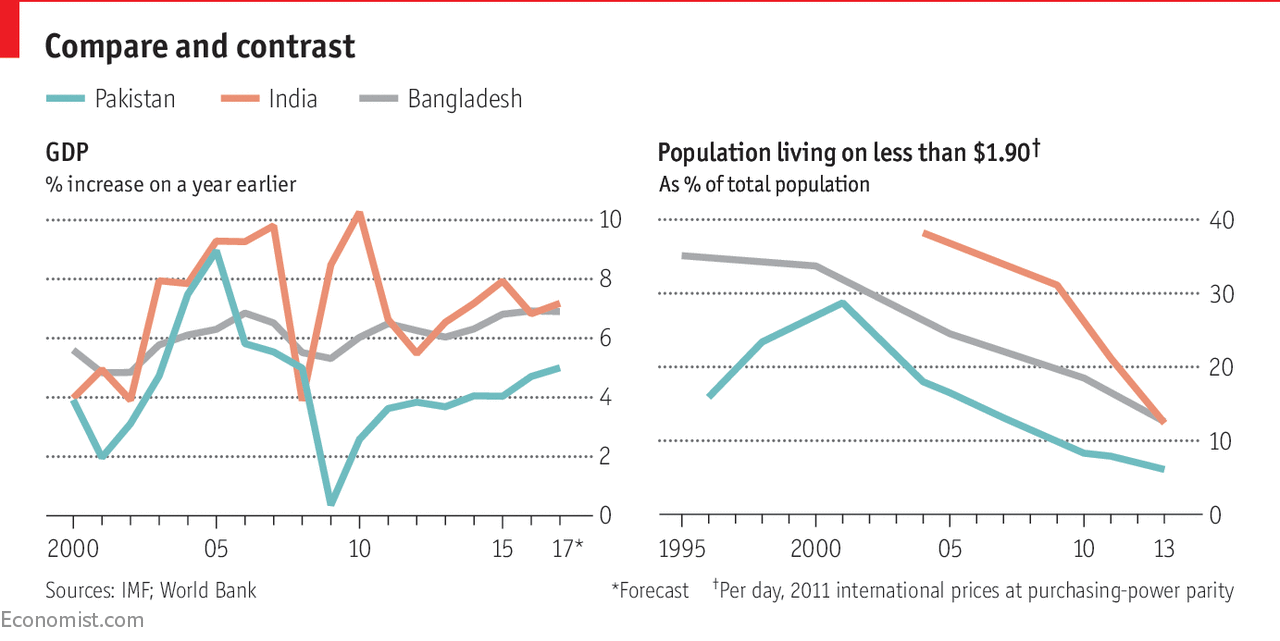

As this special report will argue, though, both Pakistan and India should more openly acknowledge the costs, to themselves and to the wider region, of their seven decades of bitter separation. These include not only what they have had to spend, in lives and treasure, on waging war and maintaining military readiness over generations, but the immense opportunity cost of forgoing fruitful exchanges between parts of the same subcontinental space that in the past have always been open to each other. Trade between the two rivals adds up to barely $2.5bn a year.

As this special report will argue, though, both Pakistan and India should more openly acknowledge the costs, to themselves and to the wider region, of their seven decades of bitter separation. These include not only what they have had to spend, in lives and treasure, on waging war and maintaining military readiness over generations, but the immense opportunity cost of forgoing fruitful exchanges between parts of the same subcontinental space that in the past have always been open to each other. Trade between the two rivals adds up to barely $2.5bn a year.

Perpetual enmity has also distorted internal politics, especially in Pakistan, where overweening generals have repeatedly sabotaged democracy in the name of national security. Pakistan has suffered culturally, too; barred from its natural subcontinental hinterland, it has opened instead to the Arab world, and to the influence of less syncretic and tolerant forms of Islam. For India, enmity with Pakistan has fostered a tilt away from secular values towards a more strident identity politics.

Reflexive fear of India prompts Pakistan’s generals to meddle in Afghanistan, which they see as a strategic backyard where no foreign power can be allowed to linger. In turn, India, because of the constant aggravation from Pakistan, has become bad-tempered with its smaller neighbours. Small wonder that intra-regional trade makes up barely 5% of the subcontinent’s overall trade, compared with more than a quarter in South-East Asia. And it is no surprise that Pakistan has opened its arms to China, which is offering finance, trade and superpower patronage.

This special report will seek to unravel the causes of this irrational enmity, and to explore the contrasting internal dynamics in both countries that sustain it. It will examine new factors in this complex geopolitical board game, such as the rise of China. And it will consider what might be done to nudge the two rivals away from the vicious circle that binds them.

No comments:

Post a Comment