Seventy years ago last week, the India Independence Act received royal assent. Suddenly George VI was a much-diminished monarch, no longer king-emperor, and the long twilight of Britain’s shameful exercise in empire had begun.

Seventy years ago last week, the India Independence Act received royal assent. Suddenly George VI was a much-diminished monarch, no longer king-emperor, and the long twilight of Britain’s shameful exercise in empire had begun.

There’s no reason you should have known this, of course, given how little is taught about imperialism anymore. But British historian Niall Ferguson certainly did. He marked the occasion by crowing that he’d “won," tweeting out a 2014 survey showing that 59 percent of Britons were “proud” of the British Empire.

Ferguson’s gloating tweet reveals the depth and danger of the myths Britain has built up around its past. Christopher Nolan’s "Dunkirk," in cinemas now, adds to the falsehood that plucky Britons stood alone against Nazi Germany once France fell, when, in fact, hundreds of millions of imperial subjects stood, perforce, with them. (Five million citizens of the empire joined up to fight the Nazis.) Countries so enormously deluded about their history make enormous mistakes: They may turn their backs on Europe, say, or seek to “recover” a relationship with former colonies that don’t want one -- or search fruitlessly for an imaginary 1950s utopia of power and wealth.

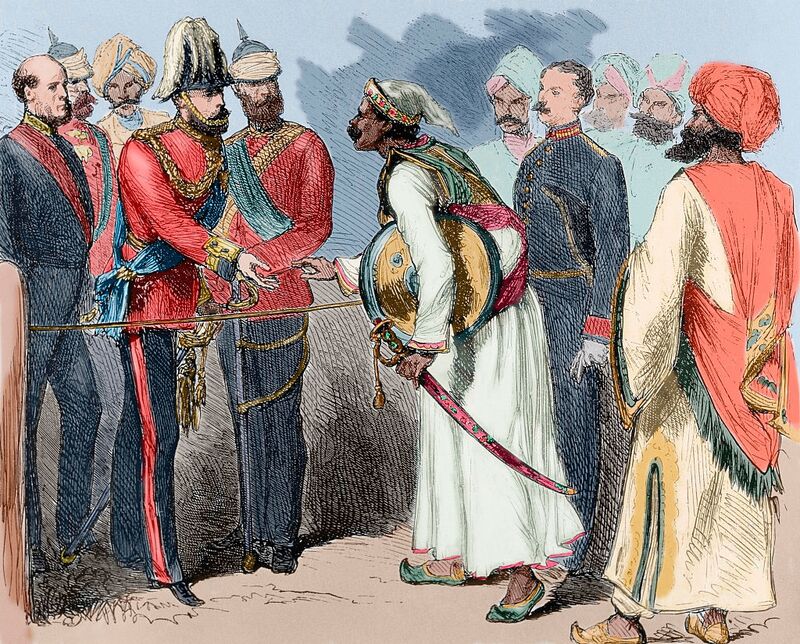

It should go without saying that the empire was not an act of altruism. It was created and sustained for British profits and to further Britons’ careers and fortunes. The “benefits,” like the railways, that it gave countries such as India were paid for, exorbitantly, by Indian taxes. And they were chosen to meet the requirements of British military rule, not Indian needs.

Was Britain at least “better” than other empires of its time, as its defenders would have it? Perhaps -- if one’s imagination is limited enough to suppose that there is a single yardstick by which imperial enterprises are judged.

In fact, every imperial power developed its own metric, and declared itself the best. The Portuguese long told themselves that they were the ideal colonialists, because “their way of being in the world” -- lusotropicalism -- was more tolerant of racial diversity and mixing. The French used to argue, and some still do, that Republican virtues of assimilation and equality meant that their empire was the only one in which individuals could rise to citizenship (presumably, if they went through their reading list from Diderot to Balzac with sufficient care). Each such myth has had a pernicious effecton the society that nurtured it.

And to the sputtering of Ferguson and his ilk, we can do no better than to quote that far more realistic imperialist, Alexis de Tocqueville: “[What] I cannot get over is [Britons’] perpetual attempts to prove that they act in the interest of a principle, or for the good of the natives, or even for the advantage of the sovereigns they subjugate; it is their frank indignation toward those who resist them; these are the procedures with which they almost always surround violence.” The public-school values of disinterested fair play the British Empire’s partisans tom-tom are all very well. But many believed in fair play in fox-hunting as well, and that was rarely of benefit to the fox.

Of course, Indians themselves have yet to come to terms with the notion that many, perhaps most, of their ancestors were passive or active collaborators with the empire for reasons that seemed to make sense at the time. (That fact was Mahatma Gandhi’s greatest insight, and the source of his power.) At the same time, many Britons -- both conservatives like Edmund Burke and liberals such as Charles Fox and William Gladstone -- tried to address the vast chasm between evolving British values at home and their repression abroad. As Fox said, in defense of his doomed India Reform Bill, “What are we to think of a government whose good fortune is supposed to spring from the calamities of its subjects?”

Indeed, one can find cause for pride in the reactions of the best men of their time to the acts and impulses of empire; in the attention to duty, intellectual curiosity and integrity of the occasional imperial official; and in the manner in which some of those who colonized and oppressed sought to blend what they inherited with what they observed. There is no time in history so dark that you cannot, if you look, find such sparks of hope and humanity.

Clear thinking from leading voices in business, economics, politics, foreign affairs, culture, and more.

But this does not redeem the notion of empire. It does not render the British Empire itself any less an enterprise founded on racism and conducted with greed. This is what the textbooks of an enlightened nation would say. Instead, the worst acts of the empire were deliberately erased by their last generation of perpetrators: It is really their destruction of records, known as Operation Legacy, that succeeded, rather than the efforts of empire apologists such as Ferguson.

The dangers are clear. A nation that turns away from the truths of its past, as Ferguson’s Little England has, runs the risk of stunting its future. Acts of colossal self-delusion, like Brexit, then become inevitable. There’s no clearer sign of a nation’s descent into self-absorption and petty nationalism than the conviction that its darkest shame is in fact its greatest glory.

No comments:

Post a Comment