Nearly two decades into the 21st Century, it has become clear the world has limited resources and the last area of expansion is the oceans. Battles over politics and ideologies may be supplanted by fights over resources as nations struggle for economic and food security. These new conflicts already have begun—over fish.

Nearly two decades into the 21st Century, it has become clear the world has limited resources and the last area of expansion is the oceans. Battles over politics and ideologies may be supplanted by fights over resources as nations struggle for economic and food security. These new conflicts already have begun—over fish.

Hungry World

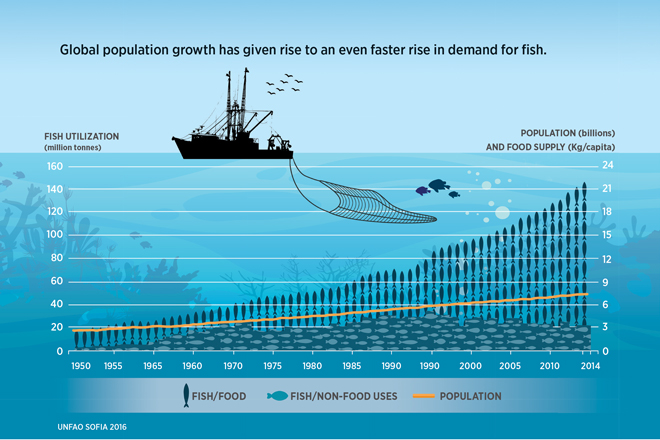

The demand for fish as a protein source is increasing. The global population today is 7.5 billion people, and is expected to be 9.7 billion by 2050, with the largest growth coming in Africa and Asia. Fish consumption has increased from an average of 9.9 kilograms per person in the 1960s to 19.7 kilograms in 2013 with estimates for 2014 and 2015 above 20 kilograms. The ten most productive species are fully fished and demand continues to rise in regions generally with little governance and many disputed boundaries.

In 2014, there were 4.6 million fishing vessels on the world’s oceans: 75 percent were in Asia and 15 percent in Africa. High seas fishing capacity has grown significantly, and there are now 64,000 fishing vessels with lengths in excess of 24 meters, and Asia’s distant water fishing nations continue to add newer and larger ships.

The wild marine fish harvest remains steady at 80 million metric tons (MMT) while aquaculture or farmed fish now equals 73.8 MMT, with China responsible for farming 62 percent of that total. 1 Farmed fish is predicted to exceed wild capture as early as 2018, but the inputs to these farming operations require massive amounts of fish meal. 2 As a result, fishing vessels will scour the oceans going deeper and farther than ever before to try to feed the world.

The world’s warming climate also will increase the demand for fish. Reports describe scenarios which will make Asia, Africa, and South America more arid, which will lead to reduced crop yields. Sea level rise and warming will alter ecosystems and move fish populations. Some islands in the Pacific will be underwater by 2050. Will these islands continue to maintain exclusive economic zones (EEZs)? If not, who will have the rights to fish in these areas? Do countries that traditionally harvest migratory fish continue to get the same quotas even if fish move to other EEZs? These questions demonstrate some of the ways that climate change will alter the status quo and impact resource security.

Protecting Fishing is Important

The United States is a significant fishing power. It has the largest EEZ in the world, almost half of which surrounds the Hawaiian Islands and the Pacific Territories. On average, the United States is the third largest producer of captured fish, harvesting approximately five MMT per year—only China and Indonesia harvest more. The United States’ largest landing port by volume of fish is Dutch Harbor, Alaska, and the largest landing port by value is New Bedford, Massachusetts.

In 2014, the United States exported $5.8 billion in edible fish products and $24.2 billion in non-edible fish products for a total export of $30 billion, and it imported $20.2 billion in edible and $15.6 billion in non-edible fish products for a total of $35.8 billion—the highest in the world just ahead of Japan for edible products. 3 The U.S. fishing industry is valued at $250 billion annually, and it supports 1.3 million jobs. 4This market position is the basis for U.S. soft power to influence the world’s fisheries, and it is in the United States’ strategic economic interest to help manage and preserve those fisheries.

Effective fisheries management and enforcement requires cooperation among nations to halt overexploitation and destruction of the resource. Annual illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing losses worldwide are between $10 and $23.5 billion or 11 and 26 MMT of stolen fish. 5 Furthermore, better management and rebuilding of stocks could yield an additional annual harvest of 16.5 MMT worth $32 billion, which could go a long way to feed the growing population. As a simplified model, consider the world’s oceans a giant fish tank where every nation takes fish from a uniform population. If the fish double every year then you can take half out of the tank—this is the maximum sustainable yield (MSY). Left unchecked, overfishing will exceed the MSY. A “tragedy of the commons” scenario would reduce fish populations to where they cannot reproduce and are overfished. 6

To avoid this outcome, Regional Fisheries Management Organizations (RFMOs) have been established by the United Nations. The entities that must cooperate to protect fisheries are the coastal state, the flag state, and the port state. The coastal states and flag states share the responsibilities for monitoring, controlling, and surveilling fishing vessels. The port state is responsible for administering a certificate documentation scheme to ensure fish landed have been caught legally. Without a robust control system, the door is wide open to IUU fishing, which can destabilize developing countries.

There are four significant fishing areas in the U.S. EEZ that require attention. The first is the U.S. and Mexico border, where there are an estimated 1,000 or more illegal fishing boat incursions per year harvesting sharks and red snappers in the U.S. EEZ. Called “lancha,” which means “speedboat” in Spanish, the boats are small, highly maneuverable fishing vessels rigged for small-scale longline or driftnet operations. U.S. Coast Guard surveillance aircraft locate approximately 200 of these vessels every year, but the few cutters allocated can only stop about 20 percent of them. This has been a persistent problem resulting in the loss of approximately 10 percent per year of the snapper catch (or $12 million) for U.S. fishermen. Drug cartels located in Playa Bagdad use illegal fishing profits to support their organizations.

New England is where the northeast multispecies, a complex of 13 species of ground fish, including cod, are harvested. In 2015, Carlos Rafael—known as the “Cod Father”—ran an organized group of fishing vessels comprising 20 percent of the permitted New Bedford fleet, which systematically overharvested and reduced the fishery.

The third problem area is in the Pacific where the Hawaiian Islands, U.S. territories, and the most lucrative tuna fisheries are found. These areas are exploited by Asian distant water fleet transnational criminal organizations (TCOs) that use support ships and forced labor.

Finally, the last area is the maritime boundary between Alaska and Russia. The Russian Mafia controls most of the fishing fleet, which is subject to the instabilities of Russian politics. 7 Disruption to U.S. Coast Guard patrols and less cooperation with the Russian Border Guard will jeopardize the 1.4 MMT pollock fishery upon which the United States depends.

In November 2015, the IUU Fishing Enforcement Act provided new authorities for combating illegal fishing. This bill increased penalties for violations and implemented the Port States Measures Agreement (PSMA) which endeavors to deny IUU fishing vessels entry into global ports. At the 2015 “Our Oceans Conference” in Valparaiso, Chile, then-Secretary of State John Kerry announced an initiative to combat illegal fishing called the Safe Ocean Network. This global initiative aims to strengthen all aspects of the fight against illegal fishing, including detection, enforcement, and prosecution through enhanced information sharing and coordinated action. The initiative focuses on four major IUU fishing problem areas around the world: the Gulf of Guinea off West Africa, the Pacific Islands, Indonesia and the Philippines, and the Bay of Bengal in the Indian Ocean. A large part of this effort was born of the Presidential Task Force report to combat IUU fishing, which made powerful recommendations related to maritime domain awareness (MDA). It establishes the requirements for intelligence agencies to search and report on potential IUU fishing activities and the ability to share information with other countries, intergovernmental and non-governmental organizations. Unfortunately, no new resources were allocated to the U.S. Coast Guard to implement the recommendations, which will clearly limit their impact.

Because of limited resources, the U.S. Coast Guard has become a global fisheries enforcement integrator. Under the Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Sea Power, the Coast Guard has partnered with the Navy and Marine Corps to provide enforcement presence where previously there was none. In West Africa, the Coast Guard annually deploys a law enforcement detachment (LED) and host-nation shipriders on U.S. Navy ships to conduct boardings to stop illegal fishing. This effort went a step farther in 2015 when an LED deployed on two Senegalese vessels during the Africa Maritime Law Enforcement Partnership run by the U.S. Africa Command. The results were impressive: 21 boardings yielded 46 violations of fisheries law during a brief operational period. In the Pacific, the Coast Guard deploys LEDs on Navy ships moving across the Pacific under the Oceania Maritime Security Initiative (OMSI) run by U.S. Pacific Command. These deployments have resulted in more than 300 boardings and 55 fisheries violations since 2008, yet are only conducted once per quarter. OMSI has been added to the Forum Fisheries Agency (FFA) regional surveillance operations which bring in French, Australian and New Zealand partners to combat illegal fishing. This is a good start, but gaps remain in the system of multilateral and bilateral agreements. The Coast Guard currently is working with the State Department to add agreements which not only include fisheries but the ability to combat criminal organizations. If a Coast Guard team conducts a fisheries boarding and finds illegal drugs, arms, or trafficking in persons, they should have the ability to act against those activities as well.

Coast Guard has Important Role

Protecting fisheries in the world’s largest EEZ is a difficult task requiring offshore presence and expertise in boarding and inspection. Boardings conducted on the fishing grounds provide a great benefit to the service. Cutter crews and boat operators reinforce critical operational skills in difficult weather conditions and on different vessel configurations. However, because of the counterdrug surge, fisheries boardings by the Coast Guard have dropped by 1,000 per year, or about 20 percent, resulting in a loss of proficiency. Boarding officers are now less experienced at interpreting complex regulations and detecting fisheries violations.

To increase proficiency and better combat illegal fishing, the Coast Guard should maintain, at a minimum, one cutter off New England, and two cutters off Alaska in the Bering Sea, Gulf of Alaska, or on the maritime boundary line. Considering these fisheries provided nearly $3 billion in at-the-dock fish sales in 2014, this is a small investment for the return. Major cutter coverage also should be provided during critical fishing seasons in other areas, including the Gulf of Mexico, Mid-Atlantic region, the Pacific Northwest, and Hawaii and the Pacific Islands. These areas should share two major cutters of coverage per year. By restoring proficiency in fisheries protection, the Coast Guard will be better able to cooperate and coordinate with international partners to combat illegal fishing and counter TCO activities.

China strives to achieve larger fish harvests each year, because the Chinese public has a distorted expectation that their fish demands will always be met. 8 Much of that demand is met by China’s extensive aquaculture operation, which contributes more than 70 percent of their fish harvest. Cumulatively, all fishing activities employ 14 million Chinese and contribute close to 10 percent of GDP. 9 Dependence on aquaculture has flaws, however. It requires protein to get a lower protein return and is vulnerable to disease and pollution. Chinese aquaculture alone consumes 40 percent of global fishmeal supply, which is expected to rise to 70 percent by 2030. 10 Fish meal and oil are harvested by vessels that capture foraging species, which are getting harder to acquire. This is a balancing act. Any of these flaws could collapse the system and send a country into a food shortage.

In Chile, for example, a large aquaculture operation has failed several times, most recently because of an algal bloom from nutrient pollution that killed 23 million fish at a cost of $800 million. 11 An incident like this could cause a chain reaction that would send China’s large fishing fleet and its coast guard far and wide to harvest the needed protein. There are signs that this system may already be failing. Recently Argentina sunk a Chinese fishing vessel in its EEZ, and South Africa arrested three Chinese vessels for illegal fishing. Japan protested 230 fishing vessels escorted by seven China Coast Guard ships entering the waters of the disputed Senkaku Islands. Incidents in the South China Sea between the Indonesian Navy and Chinese fishing vessels and China Coast Guard have escalated to arrests, ramming, and warning shots leading experts to suggest only navies and use of force can stop the IUU fishing. 12

Fisheries disputes cause conflict between countries. In 1996, Canada and Spain almost went to war over the Greenland turbot. Canada seized Spanish vessels it felt were fishing illegally, but Spain did not have the same interpretation of the law and sent gunboats to escort its ships. 13 In 1999, a U.S. Coast Guard cutter intercepted a Russian trawler fishing in the U.S. EEZ. The lone cutter was promptly surrounded by 19 Russian trawlers. Fortunately, the Russian Border Guard and the Coast Guard drew on an existing relationship and were able to defuse the situation. 14

China frequently fishes near the U.S. border, but the Coast Guard relationship with China’s Coast Guard is not as clear. The MOU 15 between the U.S. and China for combating high seas drift net (HSDN) vessels is outdated, and Chinese shipriders will not board vessels suspected of illegal fishing other than HSDN vessels. 16 Chinese Fisheries Law Enforcement Command officers firmly believe they have stopped “Chinese illegal fishing.” 17 Given the credible reporting of illegal Chinese fishing around the world, these verbal displays of cooperation hide the true Chinese government objective of harvesting increasing quantities of fish to appease public demand. Chinese government subsidies continue to fund expansion of the distant water fishing fleet. 18 China has not ratified the U.N. Fish Stocks Agreement, and further hindering cooperation is the recent Hague ruling that China has no legal basis for its claim in the South China Sea. 19,20 What will happen when Chinese fishing vessels surround a U.S. Coast Guard cutter? Will the Chinese Coast Guard protect their vessels as they did in Indonesia? The United States should pursue renegotiation of the HSDN MOU at the next North Pacific Coast Guard Forum to expand boarding cooperation.

The Chinese Coast Guard fleet now has 205 vessels available to support the questionable activities of their fishing fleet. The U.S. Coast Guard has less than half this number. While the U.S. Coast Guard struggles to meet U.S. fisheries enforcement obligations, it has little capacity to work with other countries. The United States needs to show it is serious about protecting sustainable fisheries and international rule of law. It needs a fleet that not only will provide a multilateral cooperation platform, but also take action against vessels and fleets that are unwilling to cooperate. Imposing fines and penalties on the owners of vessels engaged in illegal fishing is key to reining them in.

The U.S. Coast Guard needs to build 25 offshore patrol cutters and deploy them with the national security cutters and fast response cutters to board and seize illegal fishing vessels. 21 The Coast Guard should expand its international shiprider partnerships and increase multilateral operations to stop illegal fishing operations in other EEZs. The Coast Guard and State Department should develop mechanisms to bring China to the negotiating table to start real cooperation. Many countries are already using deadly force to stop illegal fishing. The Coast Guard should consider firing warning shots and disabling fire to stop illegal fishermen. It is imperative that the Coast Guard be prepared for when the Chinese fishing militia approaches the U.S. EEZ.

The Coast Guard should rebalance patrol efforts to a more diverse global engagement plan that involves combating TCOs by integrating with other navies and emphasizing IUU fishing in the strategy. The service needs to investigate policies for using increased levels of cooperation and a continuum of actions. Building relationships with foreign navies and coast guards will be critical to stop illegal fishing. Finally, building a larger, more effective cutter fleet is imperative for the security of U.S. fisheries and will provide leverage to support international partners. If cooperation cannot be achieved, the United States should prepare for a global fish war. Planning, cooperation, and investments today could save the greatest protein source for the future security and prosperity of mankind.

No comments:

Post a Comment