BY BEN WATSON

The bloody battle to wrest Mosul from ISIS was the world’s largest military operation in nearly 15 years.

Here’s how Western-backed Iraqi soldiers helped break the Islamic State’s grip on a city of more than 1 million people — and what we can learn from it.

DAY ONE

The Mosul offensive began on October 17, 2016, when a variegated body of more than 100,000 troops—local volunteers, regular soldiers, elite Iraqi and Western special forces—collapsed on the country's second-largest city. The force, believed to overmatch ISIS 10-to-1, moved under the cover of airpower provided by a half-dozen nations.

Advancing from the south, east and the north, Baghdad and its allies needed just 14 days to make it to Mosul’s doorstep. Iraqi special forces raced about 15 miles in those two weeks, and became the first to knock on that door. But such large-scale, coordinated assaults would prove much more difficult in the months to come.

Listen: Voices from the Battle for Mosul, featuring interviews with Brig. Gen. Rick Uribe, deputy commanding general for U.S.-led coalition forces in Iraq; and retired U.S. Army Special Forces Col. David Witty, who spent years training Iraqi special forces. Via SoundCloud, below.

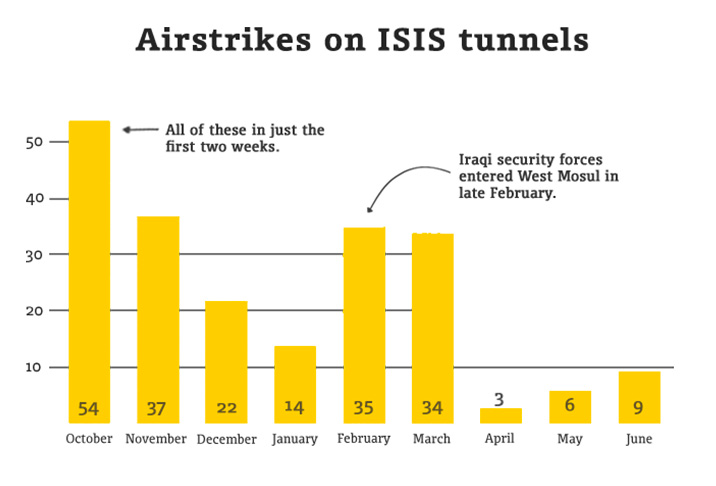

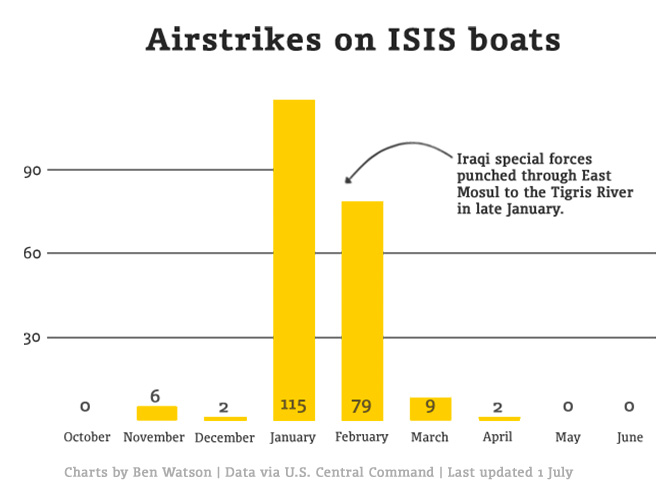

The assault on Mosul proper revealed an enemy well-prepared to grind down an attacking force. ISIS fighters used tunnels and street-spanning canvas overhangs to hide their movements. They set up artillery — both conventional and improvised. They armed a small fleet of boats for riverine combat. Most forbiddingly, ISIS laced the city with car bombs and the means to replace them.

“A lot of VBIEDs,” said the coalition's Deputy Commander, Brig. Gen. Rick Uribe, referring to vehicle-borne improvised explosive devices—what some in the military have termed bluntly "very big improvised explosive devices." “Particularly in November and December, which is when we finally got into the urban side of the city.”

Those car bombs soon were exploding at the punishing rate of five per day. “Then you had indirect fire that ISIS was using against our Iraqi Security Forces,” Uribe said.

Stuff like mortars and rockets—some stolen from Iraqi Army stocks, some manufactured from scratch. “It really was inaccurate. But they just were putting a bunch downrange,” said Uribe.

ISIS also continued to use suicide bombers, including many more children, terrorism scholar Charlie Winter noted in an exhaustive analysis of ISIS suicide operations through February. The trend would continue through the month of June.

In early November, Iraqi special forces broke through to East Mosul, where the Islamic State’s resistance stiffened markedly. The use of suicide car bombs rose steadily, as did coalition airstrikes on more than 100 ISIS factories producing them.

But the advance also yielded troves of intelligence. Iraqi troops seized the TV station and began digesting new information on car-bomb factories, artillery caches and a new weapon: armed off-the-shelf commercial drones.

By 2016, many militant groups had already put consumer drones to use for surveillance and reconnaissance, but the battle for Mosul marked the first use of armed drones by a nonstate actor. And even as ISIS was pushed from East Mosul in January, their drones grew deadlier.

It was also an easy tactic to copy.

Within weeks, Iraqi federal police had armed drones of their own. Like the ISIS versions, these were rigged to drop 40mm grenades fixed to badminton-like birdies that steadied the munitions as they fell.

HALFWAY THERE

The January 24 liberation of the city's eastern side marked the battle’s halfway point, and the coalition took a few weeks to regroup. The next phase would push across the Tigris River, whose bridges had been largely disabled. (See a detailed map of damage to Mosul's five bridges by December 5, via Stratfor, here.)

Coalition leaders used the time to review some of the more glaring tactical successes and shortcomings, said David Witty, a retired Green Beret colonel who now teaches at Norwich University. Witty, who advised Iraq’s Counter-Terrorism Service, or CTS, has published a report on Iraq’s Golden Division (also called the "Golden Knights") special forces for the Brookings Institution.

“There were a lot of mistakes made there in the first phase of the battle,” said Witty. “One of the big mistakes that was made early was that the counterterrorism service was really the only force to enter into East Mosul.”

For Baghdad, that was both a blessing—that the CTS advanced so far so quickly—and a curse, because the coalition began to rely on the special-purpose force to lead the charge. And oftentimes, alone.

“The counterterrorism service was set up to be an elite special operations unit,” Witty said. “You don't tell a Ranger battalion or a U.S. special forces battalion to go out and clear a city. That’s what you have a regular army for. The counterterrorism service, like the name implies, was an elite counterterrorism unit which is going to conduct precision range hostage rescues ambushes. It was never designed to be used the way it's been used now.”

The Golden Knights “fought in East Mosul by themselves for a good month while the other units were still outside of the city—the Iraqi army, the Iraqi federal police. It wasn't really until December when the other axes opened up and you had the Federal Police moving in, and the Iraqi army in, and they made some good progress.”

The pause appears to have given Iraqi officials time to absorb at least one important lesson.

“When they attack ISIS on multiple axes and have multiple advance routes, they’re successful. But when they only have one, it turns into a meat grinder,” Witty said. “It usually doesn’t work out, because ISIS is able to concentrate their best fighters and all their combat power on just that one axis. And that's a mistake that was made during the first half of the battle.”

No comments:

Post a Comment