ON JULY 2nd an American guided-missile destroyer sailed within 12 nautical miles (22.2km) of Triton, a tiny Chinese-occupied island in the South China Sea. It was on a “freedom of navigation” operation, sailing through disputed waters to show China that others do not accept its territorial claims. Such operations infuriate China. But they have not brought the two superpowers to blows. So far.

ON JULY 2nd an American guided-missile destroyer sailed within 12 nautical miles (22.2km) of Triton, a tiny Chinese-occupied island in the South China Sea. It was on a “freedom of navigation” operation, sailing through disputed waters to show China that others do not accept its territorial claims. Such operations infuriate China. But they have not brought the two superpowers to blows. So far.

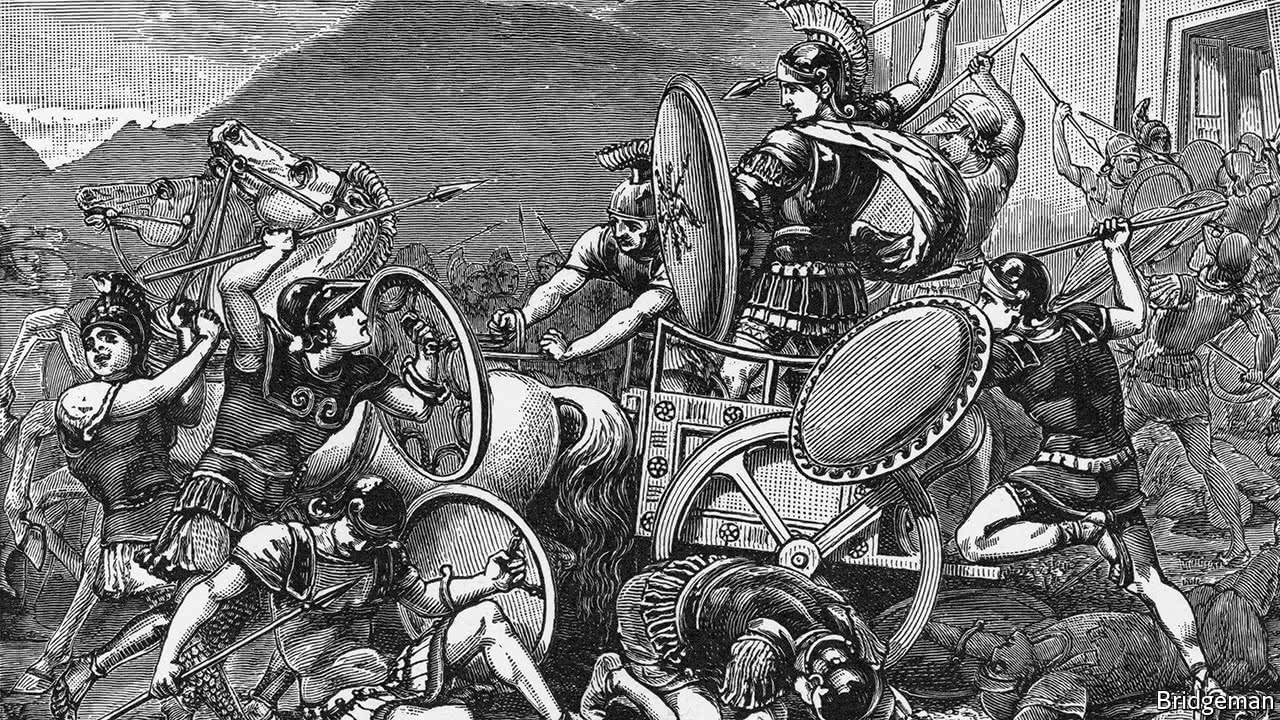

Graham Allison, a Harvard scholar, thinks the world underestimates the risk of a catastrophic clash between China and the United States. When a rising power challenges an incumbent, carnage often ensues. Thucydides, an ancient historian, wrote of the Peloponnesian war of 431-404 BC that “It was the rise of Athens and the fear that this instilled in Sparta that made war inevitable.” Mr Allison has examined 16 similar cases since the 15th century. All but four ended in war. Mr Allison does not say that war between China and the United States is inevitable, but he thinks it “more likely than not”.

This alarming conclusion is shared by many in Washington, where Mr Allison’s book is causing a stir. So it is worth examining his reasoning. America has shaped a set of global rules to suit itself. China has different values and different interests which it would like others to accommodate. Disagreements are inevitable.

War would be disastrous for both sides, but that does not mean it cannot happen. No one wanted the first world war, yet it started anyway, thanks to a series of miscalculations. The Soviet Union and America avoided all-out war, but they came close. During the Cuban missile crisis in 1962, when the Soviets tried to smuggle nuclear missiles onto Cuba, 90 miles (145km) from Florida, there were at least a dozen close calls that could have led to war. When American ships dropped explosives around Soviet submarines to force them to surface, one Soviet captain thought he was under attack and nearly fired his nuclear torpedoes. When an American spy plane flew into Soviet airspace, Nikita Khrushchev, the Soviet leader, worried that America was scoping targets for a nuclear first strike. Had he decided to pre-empt it, a third world war could have followed.

China and America could blunder into war in several ways, argues Mr Allison. A stand-off over Taiwan could escalate. North Korea’s dictator, Kim Jong Un, might die without an obvious heir, sparking chaos. American and Chinese special forces might rush into North Korea to secure the regime’s nuclear weapons, and clash. A big cyber-attack against America’s military networks might convince it that China was trying to blind its forces in the Pacific. American retaliation aimed at warning China off might have the opposite effect. Suppose that America crippled China’s Great Firewall, as a warning shot, and China saw this as an attempt to overthrow its government? With Donald Trump in the White House, Mr Allison worries that even a trade war might turn into a shooting war.

He is right that Mr Trump is frighteningly ignorant of America’s chief global rival, and that both sides should work harder to understand each other. But Mr Allison’s overall thesis is too gloomy. China is a cautious superpower. Its leaders stoke nationalist sentiment at home, but they have shown little appetite for military adventurism abroad. Yes, the Taiwan strait and the South China Sea are dangerous. But unlike the great powers of old, China has no desire to build a far-flung empire. And all the wars in Mr Allison’s sample broke out before the invention of nuclear weapons. China and America have enough of these to destroy the world. That alone makes war extremely unlikely.

This article appeared in the Books and arts section of the print edition under the headline "Fated to fight?"

No comments:

Post a Comment