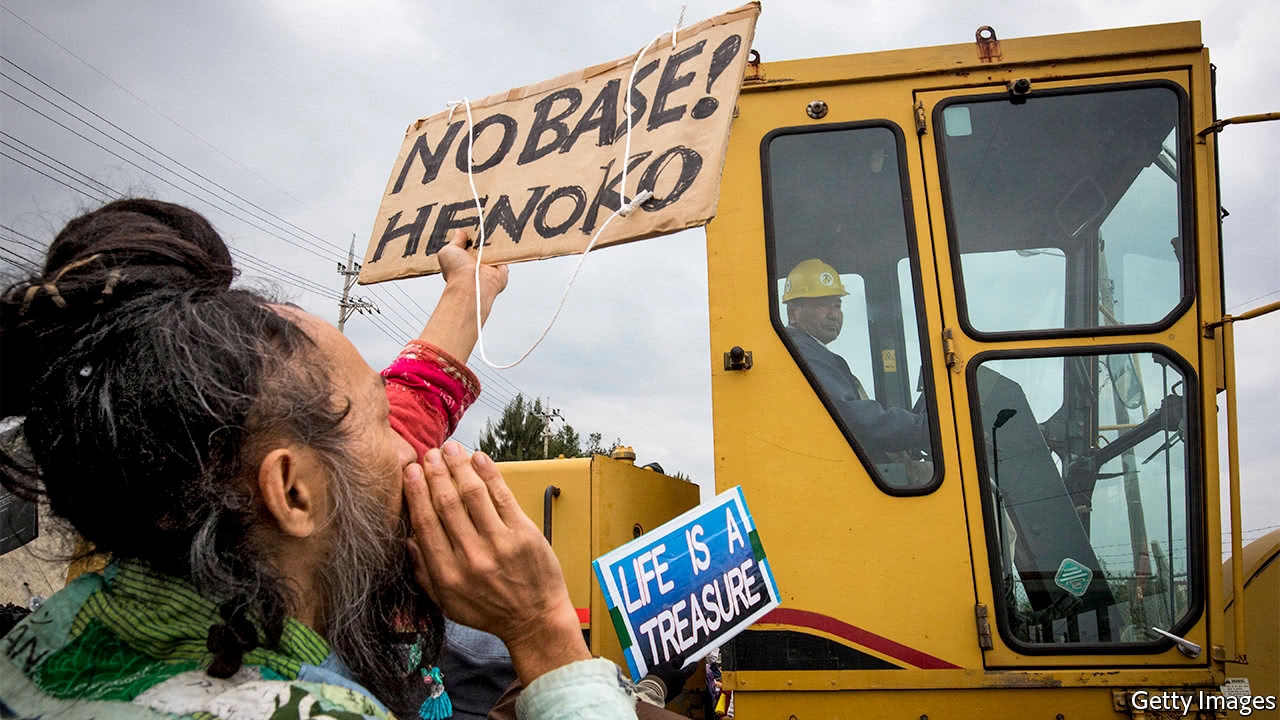

ON FRIDAY the assembly of Okinawa, Japan’s southernmost territory, is set to approve a new lawsuit to block construction of an American military base on the territory’s main island. Takeshi Onaga, the governor of Okinawa, accuses the Japanese government, which is building the base, of “barging forward recklessly” and wrecking the pristine environment of the quiet fishing village of Henoko on Okinawa’s main island. It is the latest salvo in a battle that has occupied Japan’s parliament and courts for two decades. The outcome could torpedo plans to build the offshore facility, set to be the greatest concentration of military power in East Asia.

ON FRIDAY the assembly of Okinawa, Japan’s southernmost territory, is set to approve a new lawsuit to block construction of an American military base on the territory’s main island. Takeshi Onaga, the governor of Okinawa, accuses the Japanese government, which is building the base, of “barging forward recklessly” and wrecking the pristine environment of the quiet fishing village of Henoko on Okinawa’s main island. It is the latest salvo in a battle that has occupied Japan’s parliament and courts for two decades. The outcome could torpedo plans to build the offshore facility, set to be the greatest concentration of military power in East Asia.

A subtropical speck in the Pacific 1,600km from Tokyo, Okinawa shoulders the weight of Japan’s six-decade alliance with America. Local people live uneasily with nearly 30,000 American troops and dozens of military installations, including the American marines’ oldest jungle-warfare training unit. Okinawa was occupied by the Americans after the second world war until it was returned to Japan in the early 1970s. The savage battle to take the island in 1945 left up to 100,000 civilians dead, as well as 100,000 Japanese soldiers and 12,000 Americans. Many Okinawans believe they were sacrificed as a buffer between the invading Americans and the Japanese mainland. Generations have grown up since pledging “never again”.

Latest updates

But Japan and America, once fierce enemies, now share a common concern: the rise of China. The proposed base, rising on land reclaimed from Oura bay, with a dock and two 1,800-metre runways jutting 10 metres above the ocean, is supposed to check China’s maritime expansion and maintain America’s military primacy in Asia. It is also aimed at defusing anger at the Marine Corps Air Station Futenma, which occupies nearly five square kilometres in the crowded city of Ginowan. Futenma has generated decades of complaints about noise and crime. In 1996 the two governments agreed to close it and build a replacement in Okinawa’s less populated north, after the abduction and rape of a 12-year-old schoolgirl by three American servicemen triggered mass protests. Many locals, however, want to get rid of both bases, part of a bigger demand that Japan’s mainland share a greater burden of the military alliance. Opinion polls in Okinawa put opposition to the new base at Henoko at over 70%.

Mr Onaga was elected in November 2014 on a single issue: to end construction of the new facility. He launched a series of legal challenges, culminating with a defeat in the Supreme Court last December. James Mattis, America’s next defence secretary, sought to end the long stalemate in February when he said there was no alternative to the Henoko plan. Workers have resumed dumping concrete blocks in Oura bay, the first stage in the creation of a coastal embankment. Eventually, 3.5m truckloads of dirt will be dumped over a coral reef in the bay, home to hundreds of plant and animal species, many of them rare. It remains to be seen whether Mr Onaga’s latest legal challenge will succeed. “Filling in that ocean to build a base that will be there for 200 years on land that Okinawans can’t touch would be utterly intolerable,” he told the assembly last month. The danger for the governments of America and Japan is that they will win the battle for Henoko but lose the hearts and minds of long-suffering Okinawans.

No comments:

Post a Comment