Beijing’s annual trade surplus with India is large enough for it to finance one China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) every calendar year and still have a few billion dollars to spare.

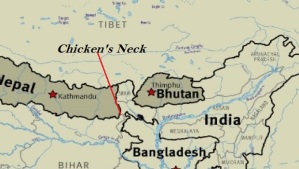

Just as Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi was meeting US President Donald Trump at the White House, Beijing ratcheted up pressure on India by officially publicizing a military standoff at the Sikkim-Bhutan-Tibet tri-junction. The shadow of China’s muscle flexing over the Modi-Trump discussions paralleled what happened when Chinese President Xi Jinping paid an official visit to India in 2014. Xi arrived on Modi’s birthday bearing an unusual gift for his host — a major Chinese military encroachment into Ladakh’s Chumar region. And Chinese Premier Li Keqiang’s 2013 visit was preceded by a 19-kilometre incursion into Ladakh’s Depsang Plateau.

In China’s Sun Tsu-style strategy, diplomacy and military pressure, as well as soft and hard tactics, go hand-in-hand. In the same way, China’s xenophobic nationalism goes hand-in-hand with its economic globalization project. Similarly, Beijing poses as a champion of free trade even as it abuses free-trade rules to maintain high trade barriers and to subsidize its exports. In effect, China has grown strong by quietly waging a trade war. China has held border talks with India while its forces perched on the upper heights of the Tibetan massif have staged fresh incursions.

In Beijing’s view, India is a critical “swing state” that increasingly is moving to the US camp, undercutting Xi’s ambition to establish a Sino-centric Asia through an expanded tianxia system of the 15th century. Given India’s vantage geographical location, China needs its participation to plug key gaps in Xi’s “One Belt, One Road” (OBOR) project. But India not only boycotted Xi’s OBOR summit but has also portrayed OBOR as an opaque, neo-colonial enterprise seeking to ensnare smaller, cash-strapped states in a debt trap.

China, by encroaching on Bhutan’s Doklam enclave, may have orchestrated the tri-junction standoff not so much to cast a shadow over the Modi-Trump discussions as to warn Modi that his increasing tilt toward America will carry long-term costs. China is already stepping up its direct and surrogate threats against India. One example is the proliferation of incursions and other border incidents since the 2005 Indo-US nuclear deal, which laid out a strategic framework for the US to co-opt India. China is also waging psy-war through media.

China, by encroaching on Bhutan’s Doklam enclave, may have orchestrated the tri-junction standoff not so much to cast a shadow over the Modi-Trump discussions as to warn Modi that his increasing tilt toward America will carry long-term costs. China is already stepping up its direct and surrogate threats against India. One example is the proliferation of incursions and other border incidents since the 2005 Indo-US nuclear deal, which laid out a strategic framework for the US to co-opt India. China is also waging psy-war through media.

With Chinese forces aggressively seeking to nibble away at Indian territory, India’s Himalayan challenge has been compounded by a lack of an integrated approach that blends military, economic and diplomatic elements into a coherent strategy. Modi, for example, has allowed China’s trade surplus with India to double on his watch to almost $60 billion. By comparison, India’s trade surplus with the US is about half of that, yet Trump wants urgent Indian action to balance the two-way trade.

By importing $5 worth of goods from China for every $1 worth of exports to it, India not only rewards Chinese belligerence but also foots the bill for Beijing’s encirclement strategy. Beijing’s annual trade surplus with India is large enough for it to finance one China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) every calendar year and still have a few billion dollars to spare. India’s most powerful weapon against China is trade. Given China’s proclivity to deploy trade as a political weapon, as against South Korea in the latest case, why doesn’t India take a page out of the Chinese playbook?

India also needs to eschew accommodating rhetoric that plays into China’s hands. Modi’s recent statement that — despite the boundary dispute — “not a single bullet has been fired” was music to Chinese ears, with Beijing going out of its way to welcome it. In truth, China’s bullet-less Himalayan aggression, as the Sikkim episode demonstrates, is similar to the way it has expanded its control in the South China Sea. Indian statements should not give comfort to an adversary that employs furtive, creeping actions to alter the frontier bit by bit.

Meanwhile, China, by arbitrarily suspending Indians’ pilgrimage to the sacred duo of Mount Kailash and Lake Mansarover, is reminding New Delhi to review its Tibet policy. To blunt China’s Tibet-linked claims to Indian territories and to defend against the growing Chinese pressure, India must subtly reopen Tibet as an outstanding issue. Theoretically, India has a better historical claim to Kailash-Mansarover than China has to Arunachal, where no Han Chinese set foot until the 1962 invasion.

Make no mistake: Despite the cosy ties with Washington, India, essentially, is on its own against China. It needs to bolster its border defences and boost its nuclear and missile deterrent capabilities. The U.S., with a price tag of up to $3 billion, is offering 22 unarmed MQ-9B unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) for surveillance, not the “hunter-killer” UAVs India needs to counter the emerging Indian Ocean threat from China. By investing that kind of money, India could develop potent new deterrent instruments against China — intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) and long-range cruise missiles, the symbols of power in today’s world.

Brahma Chellaney is a geostrategist and author.

No comments:

Post a Comment