Charles A. Flynn and Lorenzo Ruiz

“He who considers present affairs and ancient ones readily understands that all cities and all peoples have the same desires and the same traits and that they always have had them.”[1] —Niccolo Machiavelli

In a recent article, "Big Picture, Not Details, Key When Eyeing Future," General David Perkins describes how the U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command is tackling the task of preparing the Army for future warfare. He calls for a shift in strategy to “encompass more than delivering decisive battlefield firepower.”[2] Perkins describes this shift as one from playing checkers to playing chess, characterizing the complexities and requirements of future warfare. While the character of war is indeed increasing in complexity, the essence of strategy in warfare remains unchanged. Strategy remains a sum of the ways to apply means to achieve ends, and as General Perkins recognized, it involves so much more than decisive battlefield firepower.

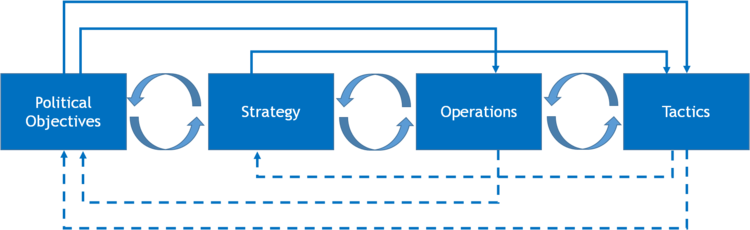

Some political and military leaders tend to think about war in terms of three hierarchical levels: the tactical, the operational, and the strategic, often displayed as a pyramid and customarily correspond to hierarchical levels in a military chain of command. These models place junior leaders at the lower or tactical level, and rightly so. However, the levels of war are also limiting because they draw divisions between interacting constructs. A more appropriate view shown in Figure 1 is what Michael Handel calls, a “complex model of interaction.”[3] This approach proposes that each level of war can influence the others, inferring more fluidity than a hierarchical view. For this reason, while junior leaders should master and live in the tactical realm, they must simultaneously think and understand the operational and strategic environments.

Figure 1: Michael Handel’s Complex Model of Interaction

Despite the U.S. military’s tactical success, evident in countless battles fought in Afghanistan and Iraq, the country largely fails to consolidate its gains and achieve desirable political outcomes. The outcomes that result from U.S. military action often expose our weaknesses and incomplete strategies at the national level. Military theorist Carl von Clausewitz describes war as a continuation of politics by other means.[4] Eastern military thinkers Sun Tzu and Mao Zedong, in contrast, describe war not as a continuation of politics but as intertwined conditions undertaken to advance interests.[5] Regardless of the sequential or simultaneous perspectives, all three strategists agree that achieving political objectives determines the success of a strategy.

We propose that the country’s recent actions have yet to yield the political objectives desired by our national leaders. Arguably, the country’s last strategic victory was achieved through the strategy of containment that led to the fall of the Soviet Union. This indicates that, fundamentally, there might be something wrong with how we think about strategy. Perhaps this is a result of when we are told to start thinking about it. Strategic thinking can and should take place at every level. Junior leaders in the military, interagency, and the whole of government should start thinking about strategic conditions, interactions, and solutions early so when they assume positions at the strategic level the country realizes better outcomes than those of the recent past.

To better explore the value of developing strategic understanding in junior leaders, this article explores flaws in strategic thinking by looking at the game of chess, a game of perfect information, a single objective, defined territory, and no regard for the state of the board after victory. Next, it looks at how the Chinese game of Wei Ch’i can offer solutions for framing a better way of thinking strategically: by focusing on positions of advantage, working with uncertainty, and linking efforts to achieve end-state conditions. Using the lessons of Wei Ch’i, we then look at how the U.S. Army’s operational variables can help us identify comparative advantages and how thinking with strategic empathy helps us understand adversaries and solve the right problems.[6] Finally, we discuss the importance of senior leaders in shaping the problem-solving skills of the next generation of strategic leaders.

STOP PLAYING CHESS

We can find some insights to our struggle with strategy by looking at games. It is widely accepted that chess is a game that sharpens your strategic mind. We associate it with great military commanders such as Napoleon Bonaparte and Robert E. Lee.[7] Although the game may offer a step in the right direction (i.e., it is certainly better than checkers), its strategic lessons are flawed.

Chess is a complex, often tiresome game. The complexities result when we must process all the possibilities that may result from one move. As in war, this is beyond human mental capacity as the possible outcomes grow exponentially for each subsequent move a player must consider. Nate Silver, a popular statistician, estimates there are more than ten raised to the ten to the fiftieth power possibilities in a game of chess, an arduous undertaking even for a computer.[8] Despite the complexity of chess, we have perfect information about the board. All the pieces in play are in plain sight and stringent rules dictate their movements. Chess is geographically linear; each side begins with a forward line of troops and must progress toward the enemy. The objective of chess is simple: checkmate the king. The singularity of the objective creates two approaches to the game. First, attrit the enemy. Second, use tactical maneuvers to achieve positions of relative advantage on the board. Both strategies focus on a single objective, checking the king, and neither consider the state of the board after the victory. This makes chess, at its heart, a decisive battle game where the end state is achieved at culmination.

Modern warfare has demonstrated that a decisive battle seldom brings strategic victory. On this issue Clausewitz quipped “the result in war is never final.”[9] Examples from history show, for instance, despite overwhelming victories on each side of the Korean War, after over six decades the conflict remains at an armistice while North Korea continues to defy international law. Likewise, despite many tactical victories, the Vietnam war ended only after the deterioration of the American will to fight. Saigon still stood when Secretary of State William P. Rogers signed the Paris Peace Accord in 1973. Despite our desire for peace, two years later the city and our embassy fell to the North Vietnamese. The Gulf War ended brilliantly. Schwarzkopf’s iconic left hook turning movement by VII Corps was a tactical and operational success. However, whether or not it was a strategic victory is less clear. The no-fly zones established after the bulk of U.S. forces left the Middle East committed U.S. air power to a prolonged policing operation. In addition, Saddam Hussein’s Ba’ath regime remained in power, this, coupled with the crippling effect of a decade of sanctions was akin to a festering wound we could not ignore a decade later. Similarly, the ongoing wars in Iraq and Afghanistan remain an irritant for our country. Libya flounders and the outcome in Syria was, until recently, almost sure to go to Bashar al-Assad and the Russians. During the latter half of the 20th century and into the 21st century, strategic victories seem to evade the United States. Modern warfare seems nothing like chess. Perhaps we need to look at a different game to frame our way of thinking.

START PLAYING WEI CH’I

Figure 2: The game of Wei Ch’i

Fiery Cross Reef. Woody Island. Mischief Reef. Spratly Islands. Paracel Islands. It is no secret the Chinese are turning reefs and rocky outcrops into inhabitable islands in a move to control the South China Sea. This should not surprise us, especially if we are familiar with the game they are playing. The South China Sea is unfolding like a real-life game of Wei Ch’i. Wei Ch’i is a 2,500-year-old Chinese game played on a 19x19 square board. The game begins with an empty board. Each player places a piece on an intersection to claim the squares, or “territories” around it. As players build up their territory, opponents can encircle, divide, and conquer by linking “territories” to achieve positions of advantage as shown in Figure 2. The game is fluid, the objective is not fixed, and players must consider not only what is on the board, but the introduction of new pieces into the mix in places you would never expect them. There is hardly a decisive battle or point in Wei Ch’i. There are many decisive moves, but how the whole game unfolds determines the victor. Furthermore, the game exhibits an interesting parallel to actual conflicts and the contest of wills in warfare: the game terminates only when neither player wishes to make another move.

To get a sense of the differences in complexity between chess and Wei Ch’i we can look at the mastery of those games by computers. In 1996, IBM’s Deep Blue beat one of the best chess players of all time, Gary Kasparov. It was another 20 years until a computer beat a human Wei Ch’i master. In March 2016, DeepMind’s AlphaGo defeated world champion Lee Sedol in four out of five games.[10] The higher degree of complexity in Wei Ch’i is better suited to training our minds for the complexities experienced in the world of conflict.

An understanding of Wei Ch’i allows us to explain China’s actions in the past century, and potentially its future moves. In a brilliant analysis, Henry Kissinger shows in his book, On China, a clear parallel between Wei Ch’i strategies and China’s actions. Both Chiang Kai-shek and Mao Zedong used encirclement strategies like those in Wei Ch’i during the Chinese Civil War.[11] In their conflicts with India in the Himalayas, China responded to new Indian outposts with Chinese outposts positioned to encircle Indian positions.[121]Kissinger concluded that the driving factor in China entering the Korean War was to prevent a U.S. position on its border.[13] The message from China is clear. When the U.S. military pivoted to the Pacific, and increased bilateral and multinational military exercises, intentionally or not, American policymakers sent an encirclement message to China. China responded, in Wei Ch’i fashion, by claiming territory in the South China Sea to break U.S. encirclement. Furthermore, China’s One Belt, One Road initiative to create a modern-day Silk Road, and their Forum on China-Africa Cooperation both appear to be attempts to gain positions of advantage in areas largely ignored by the U.S., but that could be strategically important in the future.[14]

We find a similar case with Russia. While not traditionally seen as Wei Ch’i players, we can use that particular paradigm to analyze their actions in annexing Crimea, invading Ukraine, and deploying their military to Syria. For the past 20 years NATO expanded into Russia’s area of interest, like claiming territories on the Wei Ch’i board. When Ukraine sought membership in the treaty organization, it threatened Russia’s port and strategic position on the Black Sea. Furthermore, Russia’s economy was declining; the natural gas they supply to Europe a vital part of their return to growth. The two gas pipelines planned from Iran and Qatar through Syria to Europe would undercut Russian advantage by providing Europe with an alternative gas supply. While debatable, undercutting Russia’s primacy as a natural gas exporter furthers the conclusion that Russia and China have in turn, responded to restore and maintain their positions of advantage. If we look at the future through a Wei Ch’i lens we would see our adversaries expand their positions of advantage by occupying “territories” in the world where we are largely absent—the Arctic Circle, South America, Africa, and the South China Sea.

FOCUS ON COMPARATIVE ADVANTAGES

Wei Ch’i can also teach us about developing positions of advantage, yet strategic thinking requires us to validate assumptions and identify comparative advantages as well. First, we must understand how circumstances are intertwined and connected. There are no separate levels of war; Michael Handel’s model of interaction submits that tactical actions can have strategic consequences just like strategic decisions can alter where and how the application of tactics occur. When you view the spectrum of operations, do not imagine yourself moving along in discrete phases—defensive to offensive to stability—but rather imagine that your level of effort varies widely throughout the spectrum simultaneously and across multiple domains of physical and information space.

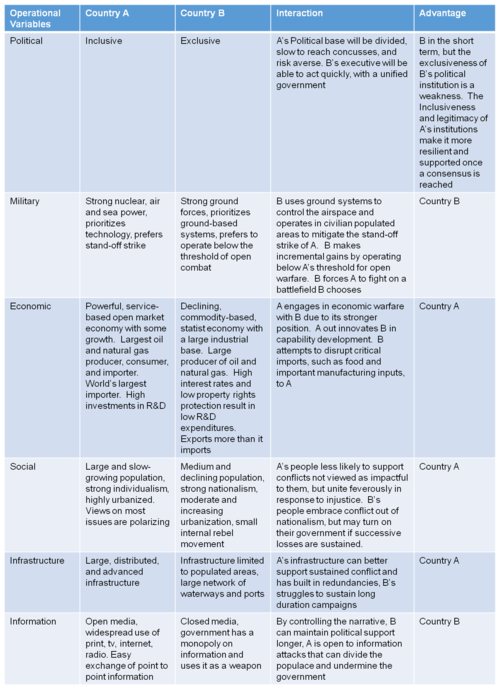

Figure 3: Operational Variable Analysis

When we remove the ways and means of strategy, we are left with the ends—the political objectives we hope to achieve. Our analysis should start from a clear understanding of these ends. Junior leaders should become increasingly more familiar in applying the operational variables of political, military, economic, social, information, and infrastructure (PMESII) when analyzing problem sets that exist between the current state and a desired end state. Operational variables assist us in understating adversaries and the strategic environment and, more importantly, lead to the identification of comparative advantages as the brief example in Figure 3 helps visualize. Sun Tzu reminds us that a “victorious army first realizes the conditions for victory, and then seeks to engage in battle.”[15] In that respect, a successful strategy is more about identifying and seizing positions of advantage across the entire physical and information domains, than tactical actions on a specific battlefield.

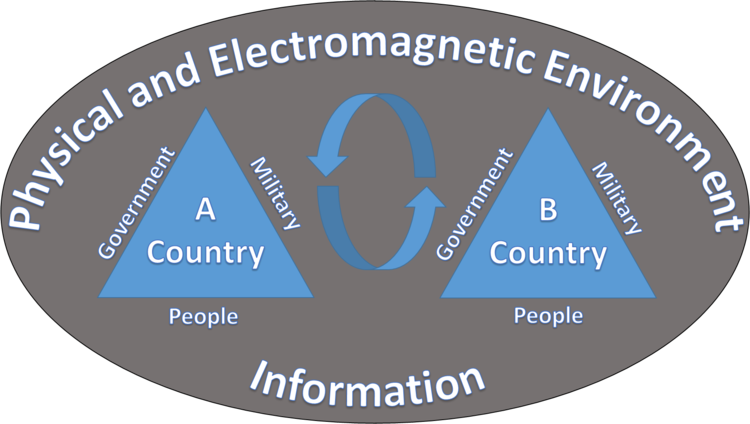

The operational variables represent an evolution of the trinity analysis that Clausewitz describes in the interaction of war’s “dominant tendencies;” the aspect of the people, the government, and the military that result in how the nature of war manifests itself.[16] Figure 4 shows each country’s tendencies interacting with the adversary’s within the physical, electromagnetic and information environment. To understand this interaction is to understand the nature of the adversarial conflict and the ultimate objectives each side hopes to achieve. We cannot develop a strategy without first understanding these interactions. Leaders often stop after they analyze an adversary’s operational variables. Even attempts at “war gaming” often fail to fully address the conditions opposing sides create when they interact. Getting this analysis right is not just about the Variables as they exist now, but what happens over time as conditions change.

Figure 4: The Interaction of War’s Dominant Tendencies

THINK WITH STRATEGIC EMPATHY

The final important lesson of Wei Ch’i is learning how to anticipate an adversary’s actions and reactions. This requires the player to look at the board from their opponent’s perspective and to plan moves based on their playing style. This is a form of empathy. The Army’s manual for leadership says that, “Army leaders show empathy when they genuinely relate to another person’s situation, motives, and feelings.”[17] Applied to the study of adversarial conflict, Zack Shore in Sense of the Enemy calls this concept “strategic empathy.”[18] It is in this area that our strategic thinkers fail most. By classifying our adversaries broadly as rogue regimes, revisionist powers, or extremists, we risk an incomplete analysis based on the mental model we create for them instead of an accurate, empathetic identification of their interests and objectives. In the opening quote to this article, Machiavelli implies that it might be easier to empathize with our adversaries if we recognize that all peoples of all cultures and times have the same desires and traits. As leaders, the more we train our minds to empathize with our adversaries, the better we identify comparative advantages and use our strengths to attack their weaknesses with the full spectrum of operations across the entire physical and information space.

One tool that can help us in this endeavor is the use of game theory to understand what decisions make the most sense from an adversary’s perspective. In Prisoner's Dilemma, William Poundstone defines game theory as the “study of conflict between thoughtful and potentially deceitful opponents.”[19] Game theory first appeared in John Von Neumann and Oskar Morgenstern’s 1944 book, Theory of Games and Economic Behavior. Von Neumann described his theory in the following statement:

Chess is not a game. Chess is a well-defined form of computation. You may not be able to work out the answers, but in theory there must be a solution, a right procedure in any position. Now real games are not like that at all. Real life is not like that. Real life consists of bluffing, of little tactics of deception, of asking yourself what is the other man going to think I mean to do, and that is what games are about in my theory.[20]

Game theory is not new to the military, it was used extensively in World War II, but has grown out of fashion due to the difficulties of quantifying player’s utility and the underlying assumption that players will make rational choices.[21] Despite these criticisms, the theory offers a model for thinking through courses of action and strategies. Much like the military’s action, reaction, counteraction approach to war gaming, game theory forces us to work through interacting decision models.

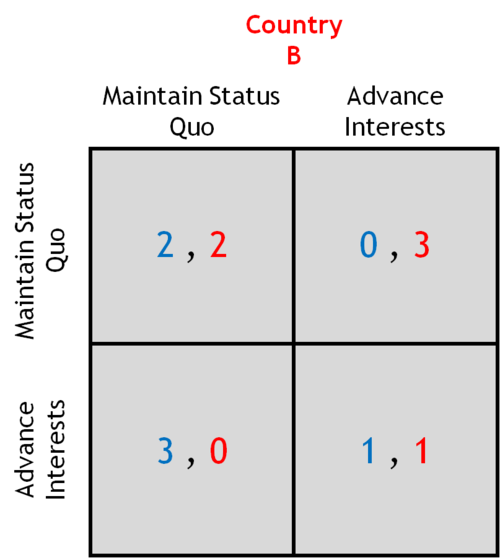

Figure 5: A simple game between two parties

A simple example of a game is shown in Figure 5. To play this game we must identify the choices we can make and the payoffs of each choice for the players involved. Figure 5 shows two countries deciding to either advance their interests, at the expense of the other, or maintain the status quo. The numbers inside the box represent the payoffs to each country, blue for Country A and Red for Country B. Clearly, each country would choose to advance their interests since that choice offers the highest payoff. However, if both countries choose this way, they come into conflict resulting in a lower payoff—less than that of the status quo. However, there is no incentive to maintain the status quo when the other side is advancing their interests.

In game theory, this situation is known as the Prisoner’s Dilemma, a condition that shows why adversaries might not cooperate despite recognizing that doing so provides the best outcome for both parties.[22] While this example oversimplifies and makes broad assumptions, the mental exercise helps us think about both perspectives and how they interact with each other to produce outcomes. This simple model helps explain why the state of world affairs is always pulling countries to advance their interests.

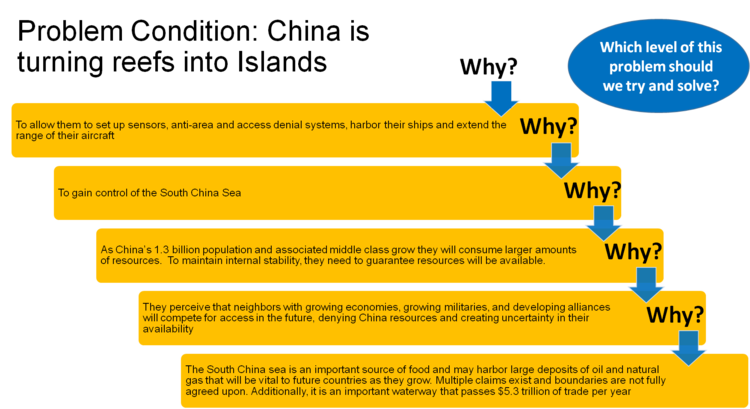

Another technique that assists us in empathizing with our adversaries is the Six-Sigma root-cause analysis known as the “Five Whys.”[23] In this approach, we ask ourselves why the current condition exists, repeating this for our answers until we are looking at the problem five levels in as Figure 6 demonstrates. Some causes may be beyond the scope of our ability to solve, but at least we gain an understanding of root causes and then can select a level to begin solving the problem.

Figure 6: Asking the “Five-Whys”

START EARLY

We can no longer hope that tactical and operational experience will produce leaders with the ability to think strategically. For this reason, junior leaders need to acquaint themselves with strategic concepts earlier in their careers. While reading, education, and using the tools in this paper are a start, senior leaders have the enormous responsibility to cultivate strategic thinking in their organizations. They must craft creative options for junior leader development to occur in their organizations so that strategic thinking is both supported and nurtured. Senior leaders have an obligation to weave strategic problems into their countless opportunities for development. They should inspire strategic professional development and shape and influence the critical thinking requirements needed for the complexities of tomorrow’s battlefields and diplomacy tables. Finally, they must identify and build on talent, despite rigid personnel systems and career timelines, and find ways to place the best and brightest into positions where their skills can be sharpened.

Chess may be good to sharpen the tactical mind, but strategy requires setting conditions beyond the battlefield, identifying comparative advantages by analyzing adversarial interactions, seeking positional advantage in the physical, informational, and electromagnetic environments, and contributing efforts to achieve political objectives. By recognizing what drives our adversaries’ actions we can more accurately apply diplomacy to keep the peace, but when required out think and outmaneuver enemies in times of war. We can use tools like the operational variables to identify conditions and interactions, the “Five Whys” to perform root-cause analysis ensuring we are solving the right problems, and game theory to improve our strategic empathy. The tacticization of strategy must be reversed. Junior leaders must start early and view their tactical actions with a strategic mind. These are just some suggestions that can help leaders at all levels avoid the strategic failures of our past.

Major General Charles A. Flynn is currently the Deputy Commanding General - South for United States Army Pacific at Fort Shafter, Hawaii. He holds an M.A. in Strategic and National Studies from the U.S. Naval War College, a M.A. in Joint Strategy and Operational Planning from the National War College, and a B.S. in Business Management from the University of Rhode Island.

Captain Lorenzo Ruiz is currently a military analyst at the Army Capabilities Integration Center at Fort Eustis, Virginia. He holds a M.B.A. from The College of William and Mary and a B.S. from the University of Texas Pan-American.

The views expressed in this article are the authors' and do not reflect the official position of the U.S. Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

No comments:

Post a Comment