FEW countries would see a tax requiring some businesses to file over 1,000 returns a year as an improvement. But India might. A nationwide Goods and Services Tax (GST) is set to come into force on July 1st. It will replace such a tangle of national and local levies and duties that even the prospect of 37 annual filings (three a month plus an annual return) for each of India’s 29 states in which a business operates is a relief by comparison.

By replacing domestic tariffs, the new tax should rid India of checkposts at internal borders, where lorries carrying goods typically languish for hours. Less red tape, however, comes with complications. Most countries with a value-added tax settle on a single rate for many goods and services. India has opted for six, ranging from zero to 28%. Officialdom decrees, for example, that shampoo, wallpaper and fizzy water are luxuries to be taxed at 28%; eyeliner, curry paste and plain water will attract an 18% levy. Restaurants will pay 12%, unless they are small (5%) or air-conditioned (18%).

Hopes that liberalising reforms would breathe new life into India’s economy have permeated the air since Narendra Modi swept to power as prime minister in May 2014. But the GST is perhaps the most obvious example of an opportunity wasted. Economists think a simple GST, which would have ensured businesses focus on goods and services that consumers want rather than those favoured by the tax code, might have added two percentage points to GDP growth. The complicated version will probably yield less than half that and only after a painful transition.

When Mr Modi was elected many business leaders (and this newspaper) winced at the sectarian and polarising bent of his Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). However, they also saw him as a reformer promising “minimum government, maximum governance”. Three years on, those hopes are fading. His supporters had hoped he would reshape the economy. They thought he was the leader to rekindle the short-lived enthusiasm for liberalisation of 1991, when India faced bankruptcy. They hoped that the state apparatus would be aimed away from trying to do everything (often badly) and towards providing basic services, such as education, health care, a functioning market for land and labour, a working judiciary, and a stable and predictable regulatory environment in which the private sector could create jobs.

Mr Modi has shown that he is an astute administrator of the economic machinery he inherited. Corruption seems to have abated, at least at the highest levels of government. But he has demonstrated little appetite for the reforms which would bring sustained growth of the sort that could transform the lives of India’s 1.3bn citizens. The few Mr Modi has carried out must be weighed against those he has botched, the areas that have gone without reform, and the sticking plasters that cover up the effects of bad policy rather than deal with their causes.

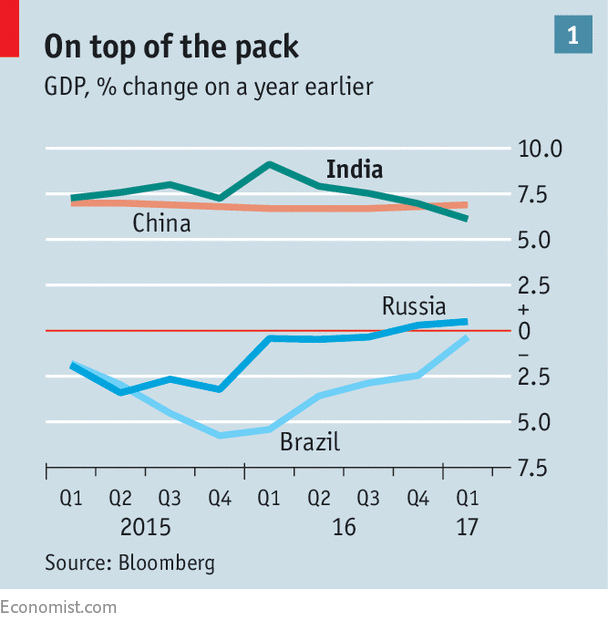

Mr Modi does deserve credit for bringing macroeconomic stability. Perennial scourges such as double-digit inflation and ballooning current-account deficits have been absent. India has until recently grown faster than all other big emerging economies (see chart 1), though plenty question the veracity of its GDP figures. The sporadic liberalisation of investment rules has helped to attract record amounts of foreign cash, albeit from an abysmally low level. The stockmarket has boomed. Tech giants such as Apple and Amazon see India as the next frontier.

Mr Modi does deserve credit for bringing macroeconomic stability. Perennial scourges such as double-digit inflation and ballooning current-account deficits have been absent. India has until recently grown faster than all other big emerging economies (see chart 1), though plenty question the veracity of its GDP figures. The sporadic liberalisation of investment rules has helped to attract record amounts of foreign cash, albeit from an abysmally low level. The stockmarket has boomed. Tech giants such as Apple and Amazon see India as the next frontier.

Luck and judgment

This is down to a mix of good fortune and good sense. The luck is oil. India is a huge importer and prices have tumbled from well over $100 a barrel in May 2014 to less than half that now. Analysts estimate that this alone has boosted GDP by 1-2%. Mr Modi also benefited from the tenure of Raghuram Rajan, a respected central-bank governor appointed by the previous prime minister, whose inflation-targeting regime has helped keep prices in check. (Mr Rajan was, in effect, sacked by Mr Modi in 2016.)

Mr Modi should also receive credit for sensibly using the oil windfall to pare fuel subsidies and keep the budget deficit mostly in check. Growth of 7% or so is nothing to scoff at. But Mr Modi’s ministers speak of an economy expanding by 8-10% a year, if not more—the sort of rates necessary to absorb the 1m Indians who enter the labour market every month. Achieving this would require deep and broad reforms.

A couple of initiatives show some promise. A new bankruptcy law, introduced in May 2016, may enable the enforcement of lending contracts. India’s judicial system is broken: more than 24m cases are pending, nearly 10% of them for over a decade. As a result even basic legal procedures, such as a bank seizing the assets of a company that has defaulted on its loans, have proven all but impossible to apply. Many lenders are waiting to see how the new law works in practice before hailing it as a success.

Mr Modi has also championed a nationwide biometric scheme known as Aadhaar, which has made many Indians visible to the state for the first time. Linking digital identities to mobile phones and bank accounts has made it possible to get subsidies straight to the needy, cutting out venal intermediaries, who in the past pilfered up to three-quarters of the money in the system. The gains made from Aadhaar could end up being sizeable.

Add in the GST, along with its many drawbacks, and in terms of big reforms since Mr Modi took office, that has been it. The problem is not that the prime minister lacks boldness. The most eye-catching economic initiative of the past three years, the surprise “demonetisation” of large-value banknotes in November, which at a stroke withdrew 86% of all currency in circulation, was certainly brave. But that did not make it sound policy. A lack of planning and unclear objectives mean the exercise has damaged the economy; its potential benefits remain hard to judge.

Despite an ensuing cash vacuum that caused distress, particularly in rural areas, it seems to have paid off politically. The BJP thumped opponents in local elections in February in Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state. Poor Indians queued for days on end to exchange old banknotes but were apparently consoled by claims that the rich were suffering far more (they were not).

The problem is that Mr Modi has shown little bravery elsewhere. Too often, he ducks essential reforms. When courting voters he talked tantalisingly about relinquishing the commanding heights of the economy to the private sector. “I believe that government has no business to be in business,” he proclaimed. But the much-discussed privatisation of state-owned firms has yet to take place. The state still makes everything from prefabricated housing and condoms to fighter jets that even its own armed forces refuse to buy.

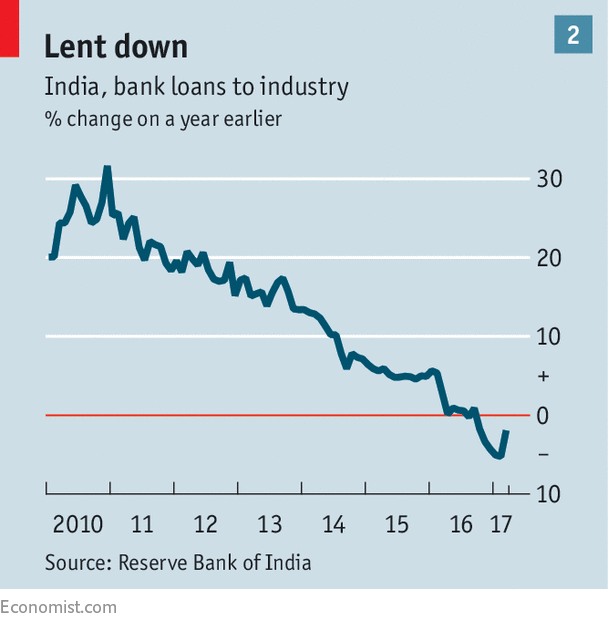

Mr Modi’s cautious approach has most obviously been found wanting in his dealings with India’s ailing financial system. State-owned banks account for 70% of all loans but are in dire straits after having extended credit to large industrial groups which went on to finance projects that failed to pay off. Around 20% of loans are either not being repaid or are likely to require restructuring. The government has known about the problem for years but has done little to resolve it.

Delhi-dallying

The upshot is that lending to industry, which once grew at a cracking rate of 30% a year, is now shrinking for the first time in two decades (see chart 2). Infrastructure projects are stalled for lack of cash and corporate India is in the doldrums. A comprehensive solution would be to let the public shareholding of banks fall below 50%, so they can be run as private companies. Instead, the quasi-bureaucrats running them are reluctant to restructure loans that are heading for default, lest they be accused of using public funds to aid tycoons.

More broadly, the state has remained front and centre in the economy, a position it shows no intention of giving up. There has been no reform of dysfunctional markets for land, labour or capital. If a business needs land, it must woo a state government which controls some, lest legal challenges on private-land purchases keep it tangled up in court for decades. State chief ministers allocate land in much the same way the “licence raj” of old doled out production quotas.

More broadly, the state has remained front and centre in the economy, a position it shows no intention of giving up. There has been no reform of dysfunctional markets for land, labour or capital. If a business needs land, it must woo a state government which controls some, lest legal challenges on private-land purchases keep it tangled up in court for decades. State chief ministers allocate land in much the same way the “licence raj” of old doled out production quotas.

Such opacity and discretion in areas of great importance to the private sector is a recipe for politicians to “pick winners”—or demand bribes. Liberalising land laws was briefly a priority for Mr Modi’s administration. But progress stalled and the tricky task was handed down to states, which share responsibility for land regulation. Only a handful have enacted reforms.

On the labour market, plans are afoot to consolidate over 40 central laws into four codes but not to repeal rules that have made companies reluctant to expand. Larger firms face stricter regulations, with predictable consequences. Only a tenth of manufacturing workers in India toil in factories with more than 200 employees, compared with over half in China. “Labour is India’s most abundant resource but the organised sector, which should be the engine for creating good jobs, has been heavily biased against using it,” says Vijay Joshi of Oxford University in “India’s Long Road”, a new book.

Staff cutbacks in some industries need the approval of the authorities. It is seldom granted; again, only a few states have picked up the baton that the centre has dropped. The costs of inaction are obvious. Around a third of young Indians are not in education, employment or training. Labour-participation rates are low, especially for women. Meanwhile, only a tiny minority of staff who are formally employed by registered firms actually benefit from the proffered workers’ rights.

More fundamentally, India lacks the capable and healthy workforce it needs to thrive. Educational standards are woeful but the government has done little to change a system where teachers bribe their way into jobs from which they can never be fired. Health care is largely in the hands of the private sector, not out of ideology but because the government has long done such a lousy job of providing it.

Capital is still viewed with a measure of suspicion and regulated accordingly. Gone are the days when ministers could press bankers into lending to their industrialist chums. But the heavy hand of the state lives on in the obligation of banks to make at least 40% of all loans to “priority sectors” such as farms and small businesses. This is on top of about 20% of banks’ lending capacity that the government commandeers for its own borrowing.

Such resolve as Mr Modi has shown has proved the exception rather than rule. To the surprise of his supporters and critics alike, Mr Modi’s searing rhetoric has been translated into incrementalism. “We elected a radical, we got a tinkerer,” rues a banking boss.

Where Mr Modi has acted it is often to tackle the symptoms of bigger problems rather than the problems themselves. His economic credibility was built during his 12-year stint as chief minister in Gujarat. His pet projects yielded tangible returns: electricity provision was improved, new roads laid, foreign investors glad-handed and bureaucrats kept honest.

As prime minister, Mr Modi has kept the focus on smaller projects at the expense of broad reforms. The government has proved adept at dealing with the consequences of bad policy rather than recasting policy itself. Power is a telling example. One government scheme put forward by Mr Modi bailed out state-owned electricity-distribution firms at vast expense, because their weak financial position was hampering efforts to electrify rural India.

The electricity firms remain fundamentally unprofitable, however, because authorities refuse to end the practice of giving farmers free power or to crack down on widespread theft by consumers (whose votes politicians crave). To avoid depending on the state grid, 40% of Indian firms therefore go to the bother and expense of generating their own electricity—building power plants and even sourcing coal.

Railways are receiving more investment, but fares remain absurdly cheap for political reasons. This means freight prices are pushed up, which then nudges companies to use roads instead. As a result, logistics costs in India are three to four times international norms (and often bigger than wage bills), hurting exports.

Modi’s operandi

The prime minister’s approach is not sweeping reform but the endless unveiling of small-bore government schemes. By one count there have been nearly 100 in the first half of his five-year term. These are hard to miss. Each is accompanied by a public-relations blitz and billboard adverts inevitably featuring Mr Modi. From encouraging more housebuilding to irrigation schemes, improving tourism infrastructure or providing subsidised loans to women to buy vans, many probably do more good than harm. But they are often aimed at providing a quick fix to a symptom of economic malaise, rather than tackling a thorny underlying cause.

The glitzy “Make in India” campaign, designed to lure foreign manufacturers, is a good example. It has loudly proclaimed the country open for business, organising conferences and photo-opportunities for Mr Modi and foreign bosses. This signalling is no doubt useful, but little has been done to tackle the shortcomings that discourage foreigners from building factories in India in the first place.

Progress on making it simpler for firms to operate has been slow. India places a lowly 130th out of 189 in the World Bank’s ease-of-doing-business ranking. Most economic activity takes place in the shadows: around nine in ten workers toil in informal jobs. One of the aims of demonetisation was to bring more of India into the open. If it has achieved that, it is only by clobbering the informal sector rather than helping the formal one.

Firms prefer to remain small because scale makes them vulnerable to corrupt officials squeezing them for bribes (or liable to filling out yet more tax returns). The country has only 270 companies with sales over $125m, compared with 1,295 in Brazil, 3,430 in Russia and 7,680 in China, according to McKinsey, a consultancy.

That is not surprising, as India still throws up the kind of regulatory surprises businesses loathe. The threat of retroactive tax rulings that claw back foreign companies’ gains, a frequent occurrence under previous regimes, is not entirely gone. Companies deemed to earn excessive profits are hounded: makers of stents, pharmaceuticals and seeds have been forced to cut prices recently.

Mr Modi’s allies are adamant that their many schemes add up to a substantial change of direction for the country. But after the headlines are printed, many come to nothing. A plan to improve the skills of 500m Indians by 2022 has been hastily dropped. A 400bn-rupee ($6.2bn) public-private fund unveiled in December 2015 to finance infrastructure is reportedly yet to find a single investor or project. “This government moves from decision to decision, without checking performance or compliance,” says a retired bureaucrat.

Arun Jaitley, India’s finance minister, begs to differ. “No government in India has reformed as much as this one,” he says. Allowances must be made for the limited resources of the state and India’s vast population, argues Mr Jaitley. But what of reforms to land, labour, tax and so on? “The Economist does not need to win votes. The BJP does.”

Are more reforms in the pipeline, Mr Modi?The answer will cheer those who think that Mr Modi is a reformer at heart and that he is simply biding his time until he secures a second term in May 2019. With even senior ministers relegated to the edges of a policymaking machine run by a tight group around him, few people know what Mr Modi has in mind. But most conclude that his core beliefs are already in evidence. And with the economy ticking along nicely thanks to the oil dividend, overhauling it has not required, or received, much attention.

Are more reforms in the pipeline, Mr Modi?The answer will cheer those who think that Mr Modi is a reformer at heart and that he is simply biding his time until he secures a second term in May 2019. With even senior ministers relegated to the edges of a policymaking machine run by a tight group around him, few people know what Mr Modi has in mind. But most conclude that his core beliefs are already in evidence. And with the economy ticking along nicely thanks to the oil dividend, overhauling it has not required, or received, much attention.

Sub-continental drift

That may have to change. GDP growth unexpectedly faltered in the latest quarter. The sag seems to have begun before demonetisation but has surely been aggravated by it. Statistics showing the creation of ever fewer jobs in the formal sector have added to a recent sense of economic malaise. Political attacks on the government’s job-creation record are common.

The response so far has not been a new resolve to reform India permanently but a swerve to economic populism. Rules issued in May to protect cows (which are considered sacred by Hindus and championed by the BJP’s Hindu-nationalist backers) have put in jeopardy a large and growing buffalo-meat export industry (see article), as well as dairy and leather producers. State governments are caving in to demands for farmers’ loans to be forgiven, a policy that will bring short-term relief but make it harder for farmers to borrow in future. It could also add two percentage points to the fiscal deficit, single-handedly nullifying the hard-won consolidation of recent years.

Even Mr Modi’s backers fear more erratic decision-making as the government aims to prove it is “doing something”. That would be an expensive way to conceal an absence of reform. Time is running out to enact genuine change. If he continues in this vein, Mr Modi will leave India a little better off but otherwise not much different from how he found it.

No comments:

Post a Comment