Anirudh Kanisett

Planet Earth’s crust is a set of massive interlocking, interacting tectonic plates, floating on its molten mantle. Above these plates, Earth’s storms, oceans, and climate buffet and shape its biomes and environments. And in them, nudged and shaped by forces which we barely comprehend, are little bubbles of human life, lines we draw on our maps called “nation-states”.

Planet Earth’s crust is a set of massive interlocking, interacting tectonic plates, floating on its molten mantle. Above these plates, Earth’s storms, oceans, and climate buffet and shape its biomes and environments. And in them, nudged and shaped by forces which we barely comprehend, are little bubbles of human life, lines we draw on our maps called “nation-states”.

As below, so above. One way of looking at the human world is to think of it as interlocking, interacting geopolitical plates, defined by climates which shape culture and history. These plates, like actual plates, have “centers of gravity”, where politico-cultural “mass” is centered, and where the central balance is to be found. A change at the center of gravity affects all states on the plate.

For the East Asian plate, the center of gravity would be China. For North America, The United States; for Europe, France and Germany.

Modern India’s geopolitics are centered around the North, and especially in the former imperial capital of Delhi. India’s strategic and security imperatives (it is argued) lie to the North-West, towards our rival Pakistan and its designs on Kashmir. If the news is anything to go by, India’s media and populace seem generally obsessed with Kashmir to the point of utter myopia towards the rest of our international actions.

The concentration of power and policy-making at modern Delhi, and its orientation towards India’s own North-West, make for a compelling case that it is modern-day India’s geopolitical center of gravity.

But has that always been the case? Where have ancient India’s geopolitical centers been? And might national interests be better served by realigning our center of gravity?

Tounderstand the geopolitics of ancient India, we need to understand the following: though modern “India” as a nation-state is a new invention, the idea of “India” as a sacred geography — bounded by the Himalayas and the three Oceans; of holy rivers and shrines; of a “Noble Land” separate from the surrounding barbarians - is very old indeed.

The Himalayas and the oceans restrict access to the subcontinent to mountain-routes (passes in Afghanistan and Kashmir), and the monsoon winds. The monsoon is the primary source of water for South India’s rivers; Himalayan snow-melt provide a perennial flow to the North Indian plains via the Ganga, the Indus, and the Brahmaputra. The Vindhya mountains mark an important divide between the two areas — the deltaic North, the peninsular South (dominated by the ancient, rocky Deccan Plateau) and the fertile areas of the deepest South and East (Tamil Nadu and coastal Andhra Pradesh). The monsoon winds break on the Western Ghats of peninsular India, and have brought trade and commerce along the coast from Gujarat to Kerala.

How has this geography shaped India’s political history?

For starters: surplus tends towards state-formation. India’s oldest cities all rose up around the Indus Valley, and declined as its course changed. Later migrations reached the Gangetic Plains and led to a second wave of urbanization. As sea trade routes developed along the coast, a later wave of urbanization began in the South, influenced by already-entrenched Sanskritic culture from the North.

India’s states have followed a wide array of strategic priorities. The early Mauryas (who established the first pan-subcontinental Empire) defeated Alexander the Great’s successors to secure Afghanistan’s passes. As they declined, these same passes provided access to invaders as varied as the Kushans, Huns, Turks, and Mongols. For thousands of years, the North-West has been the pivot to India.

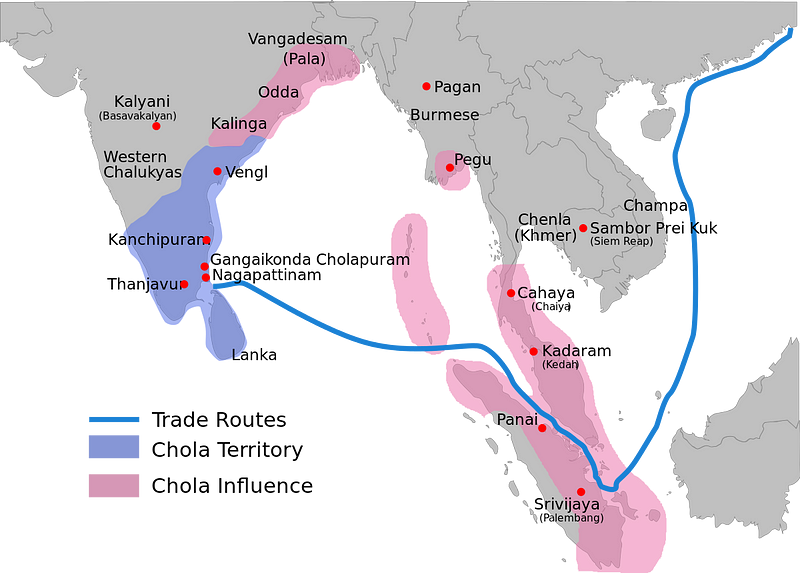

The most successful Indian empires had to secure their North-West in order to secure and expand their ambitions. Consider the Guptas, who first defeated the Kushans in the North-West before embarking on a subjugation of the South Indian monarchs. The Cholas of Tamil Nadu controlled a few Deccan choke-points, and focused on seaborne expansion into Southeast Asia.

The inability of the Sultans of Delhi to control the passes from Afghanistan allowed Babur to invade the Punjab from Kabul, and establish the Mughal Empire. The most successful Mughal Emperors effectively controlled Afghanistan and projected power into Central Asia. As focus shifted excessively to the South under Aurangzeb, the North-West was neglected — and later Mughals were crushed by invaders from Afghanistan and Persia. The British did not make this mistake, being obsessed with their North-Western frontier to the point of romanticising the “Great Game”.

For thousands of years, the North-West has been the pivot to India. The most successful Indian empires had to secure their North-West in order to secure and expand their ambitions.

Clearly, the South Asian “plate” was historically tilted to the North/North-West, in line with India’s history as a primarily continental and land-based power. But this evaluation is outdated: I present that since our northern “pole” is now relatively secure and well-defended, we can use that as a springboard to a new Southern “pole” — Chola-like maritime power projection to make the Indian Ocean region a modern-day Mare Nostrum (Our Sea).

Ask any Indian schoolkid: “What are India’s neighbouring countries?”

They’ll say: “Pakistan, Nepal, Bhutan, Bangladesh, Myanmar, Sri Lanka.” (Maybe China too if they’re the studious type).

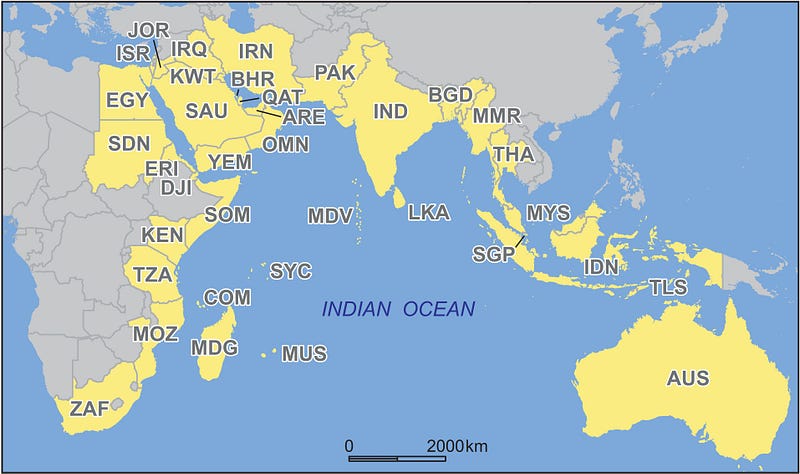

But Afghanistan and Tajikistan are (technically) neighbours to our North-West. And along the Indian Ocean, we neighbour Thailand, Malaysia, the Maldives, Singapore, and Indonesia- as well as a host of Arab and African countries. These are rarely considered to be within India’s sphere of influence- but historically, culturally, and to some extent religiously, and ethnically, they are (at least, Southeast Asian countries are).

China’s new Maritime Silk Road and One Belt, One Road are clearly historically-inspired initiatives intended to expand its sphere of influence and secure its own geopolitical imperatives, tilting the South-East and Central Asian plates North and East respectively. India can either get on board, be excluded — or increase our own mass and tilt our plate to where it suits us.

China’s new Maritime Silk Road and One Belt, One Road are clearly historically-inspired initiatives intended to expand its sphere of influence and secure its own geopolitical imperatives, tilting the South-East and Central Asian plates North and East respectively. India can either get on board, be excluded — or increase our own mass and tilt our plate to where it suits us.

With this new geo-political “plate” in mind, how can we remain the center of gravity? We need, firstly, to secure Southeast Asia via a soft-power offensive based on our ancient ties, and control of the Straits of Johor. Secondly, note that China has historically proved unable to project its power into the Indian Ocean for prolonged periods of time: India has the supply routes it needs to do that much more effectively, say in Somalia, the Maldives, and Sri Lanka. This, combined with our membership of the African Development Bank, is an excellent chance to promote our interests in Western Africa as well. To summarize: Revitalizing historic trade routes from East and West will be beneficial to all involved- and will further bolster our claims to Great Power status.

Revitalizing historic trade routes from East and West will be beneficial to all involved- and will further bolster our claims to Great Power status.

Much has been said about India’s “Panipat Syndrome”: we seem generally obsessed with the North-West but tend to do little about it until invaders are knocking on the gates of Delhi (as the many decisive battles fought in Punjab/Haryana show). Though that’s an oversimplification, it cannot be denied that despite our claims to Great Power status, we’ve done little to actually earn the title. The world’s geopolitical center of gravity is shifting to the Indian Ocean as trade and population booms. And we’re sitting right on top of it- not China.

To be frank, Pakistan is not worth the trouble or the hangover: it’s time to set our sights on bigger fish.

The world is ruled by matsya-nyaya, but the intelligent maharaja strengthens his rule by drawing his mandala of influence shrewdly and successfully.

No comments:

Post a Comment