By Fabien Merz

With the military setbacks ISIS is now experiencing, the number of jihadist foreign fighters returning to Europe will rise. Like its neighbors, Switzerland must prepare to deal with these individuals. According to Fabien Merz, there is much the Swiss can learn from the experiences of Denmark and France, including 1) there is no panacea for dealing with foreign fighters, and 2) pursuing a ‘balanced’, anti-repression approach is the most sensible way to address this problem.

With the ongoing military setbacks the “Islamic State” (IS) suffered, the number of jihadist foreign fighters returning to Europe might further increase. Switzerland, too, must be prepared to deal with these individuals. Some clues may be gained from experiences made in France and Denmark, two states particularly affected by this phenomenon.

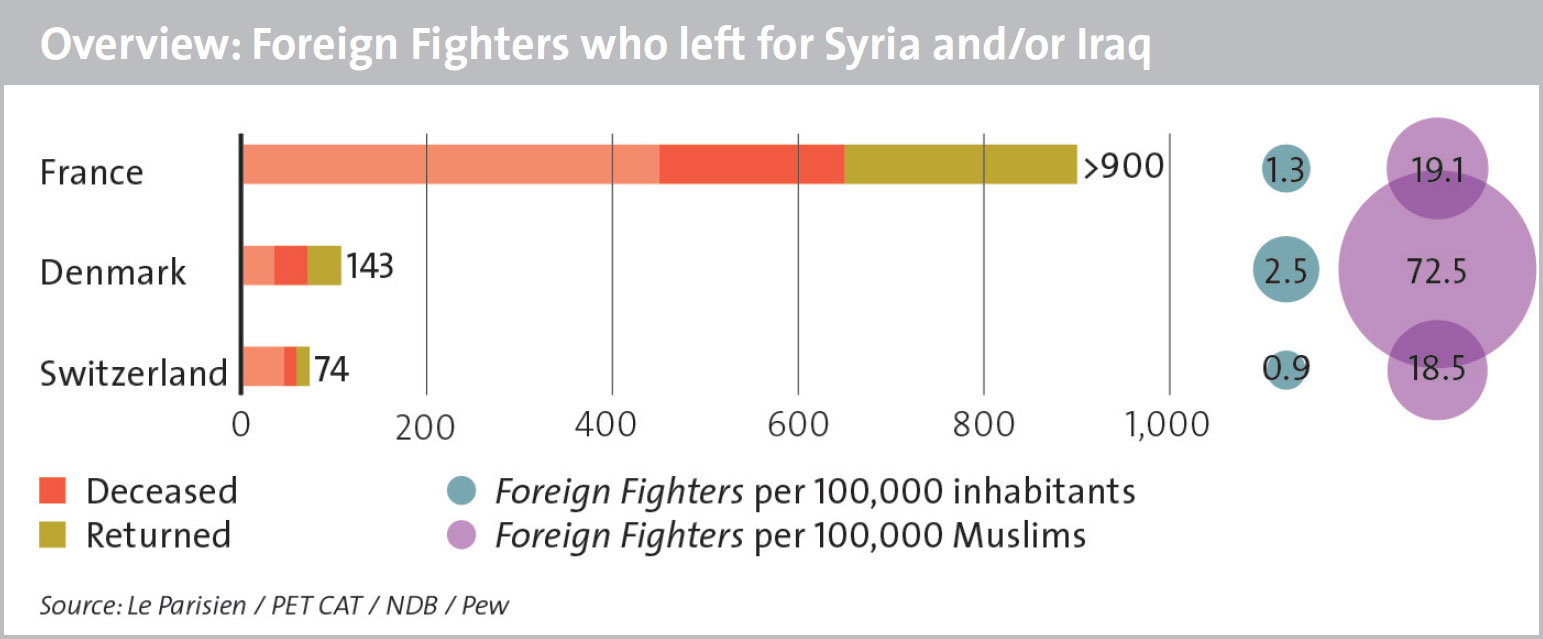

Since the start of the civil war in Syria and the resurgence of the conflict in Iraq, around 30,000 “foreign fighters” have joined jihadist militias fighting in these conflicts. Around 5,000 of them are from European countries. Many have joined IS, which has, amongst others, the stated goal of carrying out attacks in the West. This phenomenon is also of relevance to Switzerland (cf. CSS Analysis No. 199). As of May 2017, the Federal Intelligence Service (FIS) had registered 88 jihadist-inspired journeys. Of these, 74 were destined for Syria or Iraq.

IS has recently come under severe military pressure in Syria and Iraq. This has also led to a worsening of conditions for foreign jihadist fighters on the ground. Experts warn that further territorial losses by IS could lead to an increase of returnees. Thus, today more than ever, the question arises of how to deal with a potential increase of jihadist returnees and the concomitant security and societal challenges. The present analysis will only consider the post-return phase.

By now, nearly all European countries have passed legislation proscribing membership of or support for terrorist groups. At first glance, criminalizing jihadist returnees appears to be a reasonable and promising approach. However, it has often proven difficult to gather and present the kind of evidence of crimes committed in a conflict area that meets the standards of the respective criminal procedure codes. If it can be shown that a returnee has committed a criminal offence, it may be possible to contain the potential danger in the short- or in the mid-term by detaining the individuals on remand or imprisoning them. However, this might not necessarily remove the problem altogether. In fact, it can even aggravate the situation if already-radicalized individuals become more militant in prison and/or have to opportunity to radicalize other prisoners.

Therefore, a sustainable approach to dealing with this phenomenon requires that the repressive measures be complemented by others aiming at de-indoctrinating radicalized individuals to reject the jihadist ideology and reintegrate them into society. Unfortunately, there are also issues in connection with these so called “soft” measures. Deradicalization measures are complex and there is no generally applicable approach. Many such measures are still in their infancy and thus have a rather mixed track record. Furthermore, these activities oftentimes fall outside of the security services’ sphere of activity, requiring the participation of actors from the social services, the health sectors as well as civil society. This degree of diversity of actors implicated may make coordination more difficult. Additionally, there is always a residual risk that a returnee with hostile intentions may deceive the authorities, or that a person who has completed such a program may relapse.

Thus, there does not seem to be a panacea when dealing with returning foreign fighters. Experiences gathered in France and Denmark, which have been dealing with large numbers of returnees since 2014, appear to confirm this. Both countries can supply valuable pointers for Switzerland, which has, at least so far, been less affected by the phenomenon.

France: Mainly Repression

Due to experiences with terrorism made in the late 1980s and 1990s, France has traditionally followed a model of counter-terrorism that primarily relies on repression. This is exemplified by the unusually broad powers of the security services by European standards, a tough legislation with regards to terrorism, and the system of specialized anti-terrorism magistrates who are in charge of investigating all cases related to terrorism.

With more than 900 jihadists who have left the country since 2012, France is, in absolute numbers, the most affected country Europe-wide. For a long time, measures that would complement the repressive dimension, either by preventing radicalization or by facilitating deradicalization and reintegration into society, were absent from French counter-terrorism efforts. It was only after the phenomenon had drastically increased in 2013 – 4 that such measures became part of the French response to terrorism. However, these respective capacities had to be built up from scratch.

The state’s handling of the approximately 250 jihadists who have returned so far further illustrates this tendency to rely on repression. If possible, they are charged, with most of them having been detained on remand immediately after their return. The majority of the other returnees are placed under the supervision of the court, which can impose a broad range of measures, including house arrest or the obligation to report to the authorities on a regular basis. If returnees are judged to be dangerous, but the evidence against them is not sufficient to warrant detention or court supervision, they may be placed under surveillance by the domestic intelligence service.

By mid-2015, about 100 jihadist returnees had been sentenced to prison. According to the French Interior Ministry, 421 “Islamic terrorists” are currently imprisoned (as of March 2017). Since French jails are chronically overpopulated, close surveillance and individual mentoring of inmates is difficult. The resulting conditions are favorable to jihadist radicalization. French prisons have been described as “incubators for terrorism”, not just by the media, but also by anonymous sources inside the French security services. In IS’ official magazine, a jihadist and former inmate in France bragged that his time in jail had been a unique opportunity to radicalize fellow inmates. As of March 2017, in addition to the 421 inmates convicted of terrorism offenses, an additional 1,224 prisoners were considered to be “radicalized”. These inmates have not been sentenced for offences related to terrorism. It can be assumed that they were mostly radicalized during their time in prison.

Even though the problem of jihadist radicalization in the French penal system had been acknowledged for some time, the government introduced large-scale measures to counter radicalization in the penal system in a systematic manner only after the January 2015 attacks in Paris (two of the perpetrators were supposed to have radicalized while in jail). Among other measures, it was decided that radicalized inmates should be detained centrally in certain institutions so as to separate them from other prisoners and prevent radicalization from spreading to further individuals. In parallel, deradicalization programs were further boosted, and it was decided to increase the number of Muslim counselors working among prisoners.

A 2016 report by the French controller-general for penal institutions, however, criticized the authorities for having ig ignored the issue of radicalization in prison for too long. Compared to other European states, it argued, France was still far behind in this respect. The measures taken after the January 2015 attacks were criticized as ineffective or even counterproductive. The negative outcomes of these failures will likely only become apparent when individuals who radicalized or who became more radicalized in prison are released after serving their sentences.

The case of France reveals the problems that may result from excessive reliance on repression in dealing with jihadist returnees when the respective measures are not complemented by others aimed at prevention and deradicalization. While France has recently adapted and introduced such measures, both in the penal system and outside of it, it has become clear that such programs are difficult to implement effectively without experience, existing structures, or sufficient run-up time. In early 2017, a parliamentary commission published a report stating that the deradicalization programs that have been launched outside of the penal system were hastily conceived and in some cases marred by severe deficiencies.

In order to be able to build on existing structures and expertise and to exploit valuable lead time should the problem become aggravated, it therefore appears advisable to act proactively instead of reactively when devising measures that complement the repressive dimension of dealing with returning foreign fighters.

Denmark: Maintaining the Balance

Unlike France, Denmark has a reputation for adopting a balanced approach to counterterrorism. In Denmark too, jihadist returnees are prosecuted where possible. The respective legislation has recently been tightened. However, Denmark has long complemented these efforts with a strong emphasis on prevention and deradicalization. In doing so, the state can draw on decades’ worth of experience as well as structures, networks, and initiatives that in some cases go back to the late 1970s and were originally conceived for dealing with left-and right-wing extremism. Among these are monitoring programs intended to help individuals leave behind their lives of crime and extremism. In the mid-2000s, these structures were partially refocused on Islamist extremism in response to a series of international and national events linked to radical Islam (the Madrid and London bombings and the controversy over the Mohammed cartoons in Denmark).

Despite considerable efforts in the area of prevention, Denmark is one of the European countries most severely affected by the phenomenon of foreign fighters (around 143 individuals have left the country since 2012, which per capita, puts Denmark in second place behind Belgium in Europe). Aarhus, the country’s second city, was especially affected, with 31 jihadist volunteers leaving by 2013. Subsequently, a new model was developed based on the structures and cooperation networks that have existed in Aarhus for decades between the police, educators, and other actors in the sphere of violence prevention. On the one hand, it aims at preventing young people from joining groups like IS. On the other hand, an integrative approach is also adopted in order to deradicalize and reintegrate jihadists into society after their return.

Since 2014, this program has been open for returned jihadist fighters on a voluntary basis, provided they have not committed any crimes and have been screened and assessed as not posing any security risk. Participants can be supported in finding a job as well as housing and can also be provided free psychological and medical care. Specially trained mentors (including former jihadists) play an important role as reference persons for the returnees and support them in not only dealing with everyday life, but can also offer religious counseling. The aim is not to dissuade participants from their faith, but to encourage more nuanced deliberation.

However, this model has been met with some criticism. Its adherents are accused of going soft on jihadist returnees and rewarding them with free benefits. Also, as with all such programs, there is a residual risk that a participant could later take part in terrorist crimes. This, amongst other things, also implies a considerable political risk for the responsible authorities.

While it is too early to tell whether the Aarhus model will be a long-term success, a provisional assessment seems to support its advocates. Of the 16 returnees who took part in this program in 2014, none has been linked to further terrorist activities so far. Due to this positive interim evaluation, similar programs were not only introduced in other Danish municipalities but also in various cities in Europe and North America.

Denmark is thus a good example of how “softer” measures that complement the repressive element can facilitate an effective handling of issues related to returning jihadists – provided that there is a willingness to accept the associated political risk and assuming that such programs can be implemented effectively based on already existing structures and expertise.

Lessons for Switzerland

As of May 2017, the FIS was aware of 14 individuals who had returned from Syria and Iraq. While it is unlikely that all remaining jihadist foreign fighters will return home if IS suffers further territorial losses (cf. CSS Analysis No. 199), the risks associated with jihadist returnees in Switzerland should not be underestimated. As a matter of fact, most recently, a report published in April 2017 by TETRA (TErrorist TRacking), a counter-terrorist coordination body, warned of the dangers that returning jihadists pose for Switzerland’s security.

Already in October 2014, Switzerland adapted its legislation. The existing ban on al-Qaida was complemented by legislation that explicitly outlawed participation in and support for IS and related organizations. Accordingly, the Swiss authorities will initiate criminal investigations against returnees if sufficient evidence is available. In such cases, the authorities can employ the entire range of measures sanctioned by the criminal procedure code. These may include coercive measures related to criminal procedure (including detention on remand) as well as substitute measures such as house arrest, area bans, the obligation to report to the police, or a ban on contacting specific individuals.

However, problems can arise if the evidence is insufficient for initiating a criminal investigation, which eliminates the option of employing coercive and substitute measures as envisaged by criminal procedure rules. A draft law currently under consideration would permit the authorities to employ preventive policing measures outside of criminal proceedings. Some of these measures, including the obligation to report to the police on a regular basis, could also be employed in connection with jihadist returnees. The law to this effect is expected to be drafted by the end of 2017. Moreover, discussions are currently underway on further tightening existing legislation that is applicable to terrorism and raising the maximum sentences in connection with the ban on al-Qaida, IS, and related groups. Even if it still will not be possible to put every returnee under surveillance, the new Intelligence Service Act will facilitate doing this for individuals who are assessed as posing a significant risk.

Though certain gaps remain within the repressive dimension, there appears to be a political determination to provide the authorities with an appropriate set of tools for dealing effectively with jihadist returnees in terms of repression. However, the experiences gathered in France and Denmark have shown that the repressive aspect should be complemented with deradicalization measures, and possibly efforts to foster the reintegration of individuals into society, if the problems associated with jihadist returnees are to be dealt with in a lasting and sustainable manner. These country cases vividly illustrate that there is an inherent value in building up such capabilities in a timely manner and making use of existing structures wherever possible.

Switzerland is aware of these challenges. As early as October 2015, the second TETRA report emphasized the need to foster specific measures for the deradicalization of jihadist returnees. The Swiss Security Network (SSN), the coordinating body for security policy actors at the federal, cantonal, and local levels, is currently developing a National Action Plan (NAP) for combating radicalization. The NAP which aims at elaborating a national master plan including specific, and most importantly, practical measures to prevent jihadist radicalization will also specifically cover deradicalization and reintegration measures. Its aim is to help cantons and municipal authorities to build up such structures, to maintain them, and to support and further develop the already existing programs on offer. The NAP is to be approved by the appropriate political bodies in autumn of 2017. The federal administration is also evaluating how to better support such initiatives financially at the cantonal and municipal level.

There seems to be a consensus in Switzerland that a holistic approach is required in dealing with jihadist returnees. The respective impulses have been set. Under Switzerland’s federal structure, cantons and municipalities are responsible for the implementation of measures aimed at the prevention of violence and deradicalization. Unfortunately, apart from isolated examples, few concrete initiatives and programs for deradicalization are currently running. Based on the experiences made in Denmark, Switzerland, too, should increasingly check whether existing structures in cantons and municipalities, which were for example designed to support people abandoning criminality and violent extremism and to facilitate reintegration into society, could also be used for dealing with jihadist returnees. In doing so, it will be important to ensure that the existing structures have the subject-specific expertise and resources they require.

In Switzerland, criminal proceedings against terrorist acts are under the jurisdiction of the federal administration, while many efforts in the spheres of prevention, deradicalization, and reintegration fall within the purview of the cantons and municipalities. It is therefore especially important to ensure that the “soft” aspect is not neglected. This does not preclude further development of the repressive dimension as circumstances necessitate. Rather, it is crucial to ensure that at the same time, complementary efforts be undertaken in the fields of deradicalization and reintegration. The examples of France and Denmark have shown one thing: It is not only important to not neglect the “soft part” of dealing with jihadists but to develop such capabilities proactively. Switzerland would be well advised to take these insights into account when expanding the toolkit of measures that can be used in dealing with jihadist returnees.

No comments:

Post a Comment